Supplier-user teamwork key to stable oil prices

Since the early 2000s oil prices have more than tripled (Fig. 1). Prices reflect not only increasing demand and decreasing supply but broader macroeconomic and geopolitical changes such as rising exploration and production costs, the falling value of the US dollar, the reemergence of “resource nationalism,” inadequate refining capacity, and an aging labor force.

In addition, another issue has become apparent: The world likely will grow more, not less dependent on oil supplies from the Middle East.

Because high oil prices have posed serious financial challenges to many people in consuming countries, some policymakers and analysts have blamed oil companies and producing countries for the current economic slowdown.

A confrontational approach arising from these circumstances is not a beneficial tactic for dealing with high prices, however. Rather than portraying oil producers as scapegoats for the global economic malaise, policymakers can better achieve stable oil prices and markets by directing international efforts towards promoting transparency and consolidating cooperation between producers and consumers.

Supply-demand imbalance

The imbalance between supply and demand has been the driving force behind the soaring oil prices. Unlike the supply-interruption oil shocks of 1973-74 and 1979-80, the current one is a demand-driven surge, fueled by strong Asian consumption.

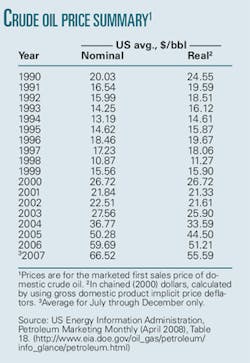

In 2008 crude oil prices exceeded the all-time inflation-adjusted high of $99.04/bbl reached in April 1980 (see table).1 The oil market has been moving away from an almost 2-decade equilibrium into uncharted territory. A close examination of oil price fluctuation suggests that the current skyrocketing has proven more sustainable than previous surges of the 1970s and 1980s.

According to BP PLC’s most recent report, oil prices have been on an upward path for more than 6 years.2 Even if prices drop back somewhat in the coming months and years, they are not likely to go back to the $20s or $30s levels. More realistically, there is a new “floor” or “plateau” that has yet to be determined.

Energy analysts at the International Energy Agency (IEA) in Paris, the US Energy Information Administration (EIA), and others argue that the price spike is being fueled by rising concerns that global supply is not keeping pace with global demand. These concerns have renewed interest in the so-called “peak-oil theory,” which suggests that oil production will plateau in coming years as suppliers fail to replace depleted fields with enough fresh reserves to boost overall output.

Other analysts and energy executives contend that the world’s fossil fuel resource base remains sufficient to support growing levels of production. Guy Caruso, head of EIA, asserts that the challenge is geopolitics not geology: “We are not believers in peak oil,” he said. “We believe the above-ground risk is the issue.”3 BP Chief Executive Tony Hayward echoes the sentiment, saying the problems in bringing on new production “are not so much below ground as above it and not geological but political.”4

Geopolitics

Oil prices reflect not only demand and supply, but broader macroeconomic and geopolitical changes. The imbalance between demand and supply has been heightened, for example, by rising exploration and production costs and an aging labor force. And the rise of “resource nationalism” has complicated the timely allocation of adequate investment and the utilization of most advanced technology.

Political calls to reduce dependency on the Middle East are unrealistic. Given their geological advantages, Middle East producers will continue to play a dominant role in global oil markets, and the world’s dependency on the Middle East is likely to expand, not shrink.

The era of confrontation between oil producers and consumers is over because the two sides, as well as oil companies, share a mutual interest in “moderate” oil prices that would contribute to stable energy markets. The International Energy Forum (IEF) can be seen as an embodiment of the current and future cooperation between major players in the oil industry.

Demand-driven price jump

A fundamental characteristic of oil policy is that today’s global oil market is overwhelmingly well-integrated. In such a global market, it matters less who buys and who sells oil. More important is the availability of enough supplies to meet growing demand. Economic growth is the single most important determinant of changes in oil demand.

As the world’s population continues to rise and living standards continue to improve, the world’s energy requirements will continue to grow apace. Over the last few decades energy intensity—energy use per dollar of gross domestic product (GDP)—has improved. As a result, the world economy is better suited to mitigate the impact of high oil prices.

In 1980 the global economy consumed 0.89 bbl of crude oil to produce $1,000 of real GDP (in 2007 US dollars), while today the global economy needs about 0.63 bbl of crude oil to generate the same economic output.5

In the last several years, economic growth, and the subsequent demand for energy, has been asymmetric. Economic growth and oil consumption in most members of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) have substantially slowed down.

Meanwhile, growth and consumption in the non-OECD countries, particularly China, India, and to a lesser extent the Middle East, have shown few signs, if any, of weakness. Indeed, China represents the single largest source of world oil consumption growth. In 2007 China accounted for half of global energy consumption growth.6

Other factors

In addition to rising demand, other factors have contributed, in different degrees, to the surge in oil prices:

• Oil companies have had to contend with rising costs across the industry. Costs for developing a new oil field have more than doubled since the early 2000s. For example, a deepwater drillship might have cost $125,000/day to rent in 2004. In 2008, it commands more than $600,000/day.10

• Refining historically has not been very profitable. The recent oil costs to refiners are shown in Fig. 2. Through much of the 1990s, refining profit margins were not sufficiently large to generate much interest in the construction of new facilities. Instead, efforts were made in the US to expand the capacity of existing refineries, a phenomenon known as “capacity creep,” which contributed an additional 1.5 million b/d capacity since the early 1990s.7

Europe has a mixed refinery outlook. Although Europe overall is relatively balanced in total oil products, there is a chronic imbalance between the supply and demand of individual products.8 In Asia, major new refineries are being built or are in the planning stage.

Several oil-producing countries recently have sought to expand their refining capacity. In 2006 Saudi Aramco announced plans to build two major refineries, one in a joint venture with Total SA in Jubail and the other with ConocoPhillips at Yanbu.9

• The “missing generation” or aging work force will retire, resulting in a shortage of knowledgeable personnel.11 The period of low oil prices that lasted from the mid-1980s to the early 2000s provided few incentives for professionals and workers, at almost all levels, to enter the oil industry. The shortage of a young, dynamic, and experienced labor force is not likely to abate in a few months or a few years. The oil industry needs to remain competitive with other industries to attract qualified engineers, geologists, and other workers and to replace the retiring generation with a new one.

• Over the last several years the value of the US dollar has deteriorated relative to other currencies. Concern over the future of the US economy and the long-term sustainability of the US fiscal and trade deficits all contributed to this depreciation. The weakening dollar, in conjunction with rising inflation and concern over a possible collapse in the value of other financial investment vehicles related to real estate and other markets, has compelled investors seeking refuge to move their financial assets to oil and other commodities funds, thereby boosting prices further. The steady decline of the US dollar means a similar decline in the purchasing power of oil exporters.

• Resource nationalism is on the rise, affecting the internal structure of the oil industry. In OPEC countries and elsewhere, oil production was wholly or mainly taken over by state-owned companies in the 1970s and 1980s.12 Today these national companies continue to dominate the industry, holding nearly 80% of global oil reserves and providing the bulk of world production. Their performance in exploration and production has been generally affected by civil unrest, government interference, corruption, inefficiency, and the diversion of capital to social welfare.13

Petroleum demand is relatively price inelastic, particularly in the short term. Changes in energy consumption patterns do not occur easily, and it takes a long time and sustained high prices to persuade energy consumers to alter the way they use oil and other sources of energy. The experience of the last several years suggests that where markets are allowed to operate, they do work. Demand for oil has declined or slowed in response to high prices.

The supply side

A key factor contributing to high prices has been the inability of producers, particularly non-OPEC ones, to keep pace with growth in global oil consumption. Despite soaring oil prices, crude output from nations outside OPEC has remained essentially flat since the mid-2000s, defying the normal link between high prices and increased production. Sluggish investment and aging fields have crimped crude production in the North Sea, Russia, and Mexico.

The long period of low prices (mid-1980s-early 2000s) contributed to a broad underinvestment in both upstream and downstream sectors. When prices started the upward trend, some oil companies were more willing to return money to the shareholders than to invest in new opportunities. Meanwhile OPEC producers were initially hesitant to commit substantial investments before being assured that the growth in demand and rise in prices were sustainable.14

Russia, the world’s second largest oil producer and exporter, has faced tremendous problems maintaining its production level since the mid-2000s. Massive development in Western Siberia allowed Soviet oil production to peak (about 12.5 million b/d) in the late 1980s.

Economic and political turmoil that accompanied the collapse of the Soviet Union led to the fall of production to about 6 million b/d in 1996. Since then, privatization of the oil industry and utilization of foreign investment and technology have contributed to a steady rise of the country’s oil production. This massive production, however, has slowed since 2005.15

Several factors contributed to this stagnation, including restrictions on foreign investment (the renationalization or deprivatization of the oil industry) and the aging Siberian fields.

Mexico, another major non-OPEC producer and exporter, has experienced a steady decline of its oil production in recent years. This decline is due largely to the peak of production from supergiant Cantarell field. State-owned Petroleos Mexicano (Pemex) holds a monopoly on oil production in the country and lacks the necessary funding for exploration and investment to reverse the production decline.16

The Russian and Mexican outlooks underscore IEA’s forecast that non-OPEC production will likely level off by the middle of the 2010s. Meanwhile, the agency projects that OPEC’s share of world oil supply will jump to 52% by 2030 from 42% in 2007.17

IEA also underscores the significance of the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region in meeting the world’s growing demand for oil. It forecasts that MENA’s share of world oil production will rise to 44% in 2030 from 35% in 2004.18

OPEC members’ contributions to world production and the challenges they face vary from one case to another. For example, Indonesia, a member since 1962, decided to terminate its membership in the organization by yearend.19 The country’s production has fallen to less than half the peak it reached in the early 1990s because of aging oil fields. Indeed, Jakarta has been a net oil importer since 2004.

Another two members, Iraq and Nigeria, face domestic security challenges. Their future production depends to a great extent on overcoming these challenges and to their ability to improve political stability.

Thus, the MENA region has been and is projected to continue to be the most influential player on the production side of the oil equation. In addition, the fact that oil revenues represent the main source of income for most MENA producers has underscored their interests in the stability of the global oil market.

While MENA producers are reaping record profits, they are concerned that soaring prices might eventually dampen economic growth and lead to global recession, which would, in time, reduce demand. (Signs of this scenario are already in place in several major consuming markets.)

Furthermore, skyrocketing oil prices make alternative fuels more attractive, threatening the long-term prospects of the oil-based economy. Thus, supporting high prices would be like “killing the goose that lays the golden egg.” In short, excessively high oil prices are likely to harm the long-term interests of major producers as much as those of major consumers. Little wonder the two sides share a common interest in restoring a sense of stability in the global oil market and in containing the volatility of prices.

Confrontation vs. teamwork

In May 2008 the US House of Representative passed HR 6074 bill, which would have created a new oil antitrust task force within the Department of Justice and would have given the DOJ authority to sue foreign oil cartels for violating US antitrust laws. The Senate, however, rejected the bill a few weeks later. These actions by the US Congress highlight the deep uncertainty in the US and around the world on the right approach to address soaring oil prices.

Instead of this confrontational approach, major producers, consumers, and oil companies have sought to lay the foundation for transparency and cooperation among all players in the industry. The move to establish a dialogue between consumers and producers gained momentum in the early 1990s.

At the initiative of Presidents Francois Mitterand of France and Carlos Andres Perez of Venezuela, major producers from OPEC and major consumers from IEA held a seminar in Paris in 1991. In this initial meeting, representatives from the two sides discussed issues of mutual concern such as economic and industrial cooperation. Their discussion helped to alleviate earlier mistrust that had characterized the global oil market in previous decades. Since then, meetings between the two sides have been held on a regular basis.20 These meetings, known as International Energy Forums (IEF), developed from a ministerial seminar and workshop to become the largest recurring global gathering of energy ministers.21

When Saudi Arabia hosted the seventh IEF meeting, in 2000, then-Crown Prince Abdullah Ibn Abd al-Aziz proposed to establish a secretariat in Riyadh for the IEF. The proposed International Energy Forum Secretariat (IEFS) was officially endorsed by the eighth ministerial meeting in Japan in 2002 and started working in Riyadh in December 2003.

IEFS’s executive board consists of representatives from producing and consuming countries, as well as both IEA and OPEC. IEF and IEFS have contributed to a growing awareness of long-term common interests among all major parties in the oil industry.

The Joint Oil-Data Transparency Initiative (JODI) was launched in June 2001 to assess the quantity, quality, and timeliness of basic monthly oil data. Currently, more than 90 countries representing more than 90% of global oil supply and demand are submitting data to JODI. The data cover production, demand, and stocks of seven categories: crude oil, liquefied petroleum gas, gasoline, kerosine, diesel oil, fuel oil, and total oil.22

Parallel to the IEF gatherings, IEA and OPEC have held a series of joint workshops since the early 2000s, which demonstrates a further strengthening in the dialogue and cooperation between the two organizations. The first two workshops concentrated on oil investment prospects. The third one, held in Kuwait City in May 2005, focused on the economic prospects for the MENA region and its energy supply and demand prospects. In May 2006 a fourth joint workshop was organized in Oslo, where participants discussed global oil demand.23

The steady rise in oil prices since the early 2000s has further intensified the efforts for transparency and cooperation. Heads of state and government of OPEC members held a third summit in Riyadh in November 2007. In the Riyadh Declaration, OPEC members agreed on three themes: stability of global energy markets; energy for sustainable development; and energy and environment. They underscored the interrelationships between global security of petroleum supply and the security and predictability of demand. They also pledged to renew efforts to bridge the development gap and make energy accessible to the world’s poor while protecting the environment.24

In June of this year all major players in the oil industry held a meeting in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, to address rising oil prices. The joint communiqué underscored several themes, most notably the importance of improving the state of transparency and improving the standards relating to the market’s data and information quality based on the JODI.25

Seeking to address rising fears that future world supplies may not match rising demand, Saudi Arabia promised an aggressive campaign to push its overall output capability to as much as 15 million b/d by 2018 from about 11.4 million b/d in 2008.26

The way ahead

There is no guarantee that promises of full cooperation and transparency or of investment and production increases will be completely fulfilled. Still, a major achievement is that the dynamics of global oil markets at the end of the 2000s are fundamentally different from those of the 1970s. The underlying consensus is that soaring oil prices are destabilizing global energy markets and the global economy. Ultrahigh prices are not serving the interests of either producers or consumers. They need to be vigorously addressed by joint efforts between the two sides. For the foreseeable future, the following trends are likely to prevail:

- Oil prices are not likely to keep rising forever. Since July oil prices have been declining. However, the days of cheap oil are over. Prices are highly unlikely to go back to the $20 and $30 levels. For oil prices to fall significantly, either the world economy has to experience a deep and sustained economic recession or alternative sources have to become commercially and environmentally viable in a timely fashion; neither development is likely to take place in the near future. Major industry organizations such as IEA and EIA project high prices for the next few decades.

- The energy future is not completely bleak. There are some grounds for optimism. At today’s prices, investment in marginal oil fields becomes attractive, as does the development of alternative energy sources. Prospects of expanding production in the Caspian Sea, deepwater fields off Australia and Brazil, and in the Gulf of Mexico are promising. Meanwhile, global oil consumption is slowing and in some major markets, declining. In short, market laws are working—production, consumption, and investment are responding to price signals.

- Alternative sources have recently proven competitive in the industrial, commercial, and residential sectors. In the transportation sector, however, oil remains and is projected to continue to be the dominant fuel. Furthermore, the MENA region’s substantial geological and geographical advantages suggest that the world is likely to grow more dependent on oil supplies from the region.

Concentrated efforts to address the region’s geopolitical issues such as terrorism and instability in Iran and Iraq would alleviate the so-called “fear premium” and further stabilize oil markets and prices.

References

References are available from the author upon request.

The author

Gawdat G. Bahgat ([email protected]) is professor of political science and director of the Center for Middle Eastern Studies at Indiana University of Pennsylvania in Indiana, Pa. He has taught at the university for the past 11 years and has held his current position since 1997. He also has taught political science and Middle East studies at American University in Cairo, the University of North Florida in Jacksonville, and Florida State University in Tallahassee. Bahgat has written and published six books and monographs on politics in the Persian Gulf and Caspian Sea and more than 100 articles and book reviews on security, weapons of mass destruction, terrorism, energy, ethnic and religious conflicts, Islamic revival, and American foreign policy. His professional areas of expertise encompass the Middle East, the Persian Gulf, Russia, China, Central Asia, and the Caucasus. His latest book is Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons in the Middle East (2007). Bahgat earned his PhD in political science at Florida State University in 1991 and holds an MA in Middle Eastern studies from American University in Cairo (1985) and a BA in political science from Cairo University (1977).