Norwegian groups study drillers’ work

Norway’s Petroleum Safety Authority surveyed drillers to better understand human factors affecting safety in drilling and well operations.

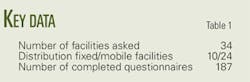

Drillers working on 34 different drilling units on the Norwegian Continental Shelf responded to a questionnaire. The survey was a joint project between Norway’s Petroleum Safety Authority and Det Norske Veritas, with input from 187 drillers working for eight drilling contractors operating floating and fixed drilling units in 2007.

Drilling and well operations are potentially risky. Breakdown in the interaction between human beings, technology, and organizational problems can contribute to serious incidents.

In autumn 2005, the Petroleum Safety Authority Norway (PSA) and Det Norske Veritas (DNV) prepared a report entitled ”Human Factors in drilling and well operations.”1 At that time, drillers’ work emerged as an area requiring further study. The data presented in this article are part of the follow-up to the 2005 report.

Purpose

The purpose of the study was to provide drilling companies with insight into potential risk factors linked to drillers’ tasks so that they can work independently to prioritize improvements. PSA and DNV also wanted an overview of how drillers perceive their own work.

Method

In spring 2007, the PSA approached nine drilling contractors that operate on the Norwegian shelf. These contractors were asked to complete a questionnaire to map how drillers perceive their own work on at least one mobile and one fixed facility (where relevant). The PSA requested the following information:

- Summary of responses from individual drillers.

- Short presentation of potential measures identified by the company to follow-up any identified factors.

- “Positive stories” in the improvement work.

Eight of the contractors chose to participate, and their responses form the basis for this article, which excerpts a report by the PSA.2

PSA and DNV prepared the questionnaire in connection with audits in 2006. DNV prepared an interview guide based on issues that emerged in previous work on “Human Factors in drilling and well operations,” which was used in a PSA workshop.1 Drillers from three different drilling contractors also provided input for the questionnaire.

As a consequence of the survey, the companies have identified areas with potential for improvement. The feedback received from the companies indicates that concrete measures have been implemented to varying degrees. In addition to a general compilation, the companies that participated in the survey received individual feedback regarding their own results and follow-up.

PSA and DNV elected not to use statistical tools to evaluate the collected data; therefore, only general trends are examined and qualitative evaluations presented here.

The PSA presented the most important results of the study at a seminar in December 2007. Some of the companies involved presented their experiences and intended follow-up.

Scope

The study sheds light on the drillers’ work on the Norwegian shelf. Among the positive feedback is that interaction between management and drillers, as well as among colleagues, is perceived as being good in all of the companies. Another positive factor is that several companies have outlined measures to respond to identified issues.

Based on the drillers’ own perception, some issues remain regarding the drillers’ daily work, related to:

- Workload and responsibility.

- Management.

- Competence and understanding of risk.

- Procedures—formulation and compliance.

- Physical design of the drilling area.

- Design of the drilling systems, including handling of alarms.

Requirements, role clarity

In the survey, the drillers respond that they know what is expected of them on the job. After their free periods, the drillers need to acquaint themselves with certain new circumstances but most still feel that they have control over their work. The drillers rarely find their tasks too difficult.

A central problem in the driller’s workday is that about half of them feel they have too many tasks and, from time to time, an excessive workload. The actual job done by drillers is demanding in the sense that some aspects must be constantly monitored and require an immediate response. The drillers’ perception is that a substantial amount of their time is spent on administrative tasks (including logging of the work performed) and on daily maintenance.

In addition, the drillers experience two main disruptions during the workday: the telephone and people in the driller’s cabin. The drillers state that there is an unnecessarily high volume of phone calls to the driller’s cabin. Some of them find it difficult to admit the presence of other personnel is a disruption.

One driller commented on job demands: “In connection with hectic or critical situations and a lot of inquiries via telephone and radio, the driller’s cabin might be full of personnel, which can be a distraction. Downtime is a burden as we have to do everything possible to avoid it, while at the same time we cannot control situations involving equipment failure, computer problems, etc.”

One fourth of the drillers state that they sometimes work so hard that they are pushing the limit of what is prudent. Most feel that they are chained to the operator’s chair in the driller’s cabin. It is also worth noting that one-third of drillers state that they sometimes lose concentration when sitting in the chair and that they have trouble staying awake throughout the entire shift.

Most drillers respond that they are relieved from duty when they need it. At the same time, one half of the drillers state that it is not always possible to take a break when they feel it necessary. One third of the drillers say that they rarely speak when they have too much to do. It is therefore important to emphasize openness and good communication.

Company response

Examples of how the companies regulate use of the telephone in the driller’s cabin:

- Strive to change attitudes. Get the message out to all personnel on board—least possible disturbance of the driller through phone calls. Call the assistant driller instead.

- Close telephone lines from land.

- Give first priority to radio communication.

- Introduce cordless telephone with number display so the driller does not have to stretch to reach the telephone.

Examples of measures to control access to the driller’s cabin:

- Restrict use of the driller’s cabin as a meeting room.

- Change attitudes. Get the message out regarding restricted access. Consider how information regarding disturbances in the driller’s cabin can best be communicated to relevant personnel.

- Encourage drillers to speak up if there are still too many people in the driller’s cabin.

Measures at companies to reduce job demands include:

- Review the drillers’ work together with the drillers, with the goal of drawing up guidelines for workloads and quality assurance of work programs.

- Appoint a working group of personnel responsible for HSE. The rig management, driller, and assistant driller should examine shift schemes, review the opportunity to take breaks, and provide varied work.

- Make greater use of relief from assistant driller and tool pusher.

- Introduce “quiet days.” This measure entails reducing the number of morning meetings to 3 days from 5 days/week. In addition, e-mails are not sent offshore unless they involve critical information.

- Develop integrated operations, unload administrative routines, and plan better.

- Develop the “rig manager” program, which contains a planning module for both maintenance and drilling. This insures that the drilling program incorporates important maintenance tasks.

Management, colleagues

The drillers in the study say that drilling supervisors or tool pushers are involved in the work and there is sufficient support and help from management when needed. Drillers’ experience, however, that the tool pusher or drilling supervisor prioritizes meetings ahead of the actual drilling operations. Moreover, drillers feel they lack feedback regarding work performed.

Only a few drillers feel that they have sufficient time and resources to function as a work supervisor. In spite of the time pressure, they assess their own efforts as supervisors to be good. They are particularly concerned that the drilling crew has a good understanding of risk, both in general and in particular for the work to be performed.

Drillers in all companies feel that there is a good environment on the shifts and that they receive help and support from each other. One driller commented on the support from management and colleagues as follows:

“When the workload is high, recognition of this would be appreciated. Our leaders do not pressure us into speeding up. They say…take the time required to perform the function safely and with the desired outcome.”

Companies proposed several modifications in management, particularly the need to provide training in:

- The responsibility that follows with the leader’s role, including the importance of giving feedback both on a daily basis and in more formal aspects.

- Addressing employee appraisal conferences.

Procedures, program

Most drillers say that they follow procedures. At the same time, most say that, from time to time, there are too many administrative systems and procedures. In some companies, this results in drillers taking shortcuts.

One third of the drillers said that, for some work operations, they do not know if procedures exist, while 20% state that they do not always have time to read the applicable procedures. In total, 7 of the 187 drillers responded that they often take shortcuts in relation to the procedures.

One driller put it this way: “It creates uncertainty when the company, the operator, and the authorities have procedures and guidelines that cover the same topic. [They must] try to ensure that we as users have one document to deal with.”

Nearly one half of the drillers feel that the work programs are difficult to understand. This may be because some drillers say that they have little time to check the work program in advance. Some drillers also say there are times when the daily work programs are not signed by the tool pusher or drilling supervisor. This could indicate a lack of quality assurance of the work program.

Companies have proposed several improvements in procedure:

- Make procedures more user friendly and appropriate.

- Review existing procedures to reduce the number of documents.

- Make procedures more easily accessible. For example, they should be stored where the work is performed.

- Improve knowledge of existing procedures. This may be part of a general need for training and the methods that introduce new personnel to rig-specific factors or procedures.

- Introduce periodic procedure courses to maintain awareness of procedures.

- Review the mentor arrangement to ensure transfer of the company’s desired attitudes and values to new employees, including the principle that procedures must be used and followed.

Examples of measures the contractors plan in relation to the work program:

- Check whether necessary time is allocated to qualify the work program before the work is started.

- In cooperation with the operator, ensure there is adequate time to review the work program.

Technical systems, physical aspects

Drillers’ perceptions of the technical drilling systems in the driller’s cabin and the physical working conditions in the drilling area vary among companies and facilities. Some main trends, however, are evident from the responses regarding physical working conditions, alarms, and drilling systems.

• Physical working conditions. According to the survey, 47% of drillers are satisfied with the physical design of the driller’s cabin. Half of drillers experience muscle pain and eye fatigue when operating the drilling system. This can, in part, be linked to long, high-pressure working days during which the driller feels chained to the work chair.

Work as a driller can result in strains on eyes, neck, back, and arms. The drillers’ physical ailments may be directly connected to the design of the technical systems and physical conditions. The survey shows a need for a review of the driller’s cabin and the drilling systems on many of the facilities.

A risk factor that emerges from the survey is that 24% experience poor visibility from the driller’s cabin. Good visibility of the activity on and above the drill floor is a prerequisite for safe drilling operations. Poor visibility could lead to the driller assuming an unfortunate working position in order to see more clearly, which can lead to unnecessary strains in the musculoskeletal system.

Other factors that emerge in the survey include irritating noise and bothersome odor from oil vapor. Unfortunate working postures and irritating noise may be factors that contribute to drillers often feeling tired during a shift.

• Alarms, drilling systems. Most of the drillers state that they know what to do in connection with the various alarms.

Several surveyed, however, said that alarms do not function properly. Examples include:

- A large number of unnecessary alarms—that is, alarms to which drillers do not respond (56% of respondents).

- The alarm system does not provide support in connection with interruptions in operations, i.e., the system does not provide guidance as to the actions the driller should take (21%).

- The drilling system does not provide support in connection with critical situations—situations in which the driller needs support from the system (19%).

- The drilling system rarely provides an early warning when something is wrong (23%).

- Critical actions linked to alarms or the drilling system in general do not always require a confirmation (34%).

Both during operations and particularly in connection with critical situations, it is important that the drilling system and the alarms provide support for the driller and help to prioritize the most important tasks at any given time so that he or she can concentrate on carrying out the correct actions at the right time. Drillers feel that there is room for improvement in this area.

Another aspect of the technical systems is the visual displays. The feedback from drillers is inconsistent in this area. A majority respond that the visual displays provide support and assistance and that they provide a good overview of the operation. In spite of this, nearly half the drillers feel there is too much information to deal with. They also experience that the drilling system provides too many opportunities to change variables in the displays, so that the information is not consistent.

The mix of old and new systems on several facilities means that drillers must deal with multiple systems with considerable differences in how information is presented. Coordination of the systems (e.g., a review of how information is presented) can help achieve a manageable volume of information, as well as fewer units of measurement to deal with.

Several other publications provide guidelines for the evaluation of alarm and drilling systems.3 4

The companies proposed several measures in connection with physical aspects and the drilling systems:

- Map the physical design of drillers’ cabins on all rigs together with drilling personnel and personnel with expertise in ergonomics and human factors. Based on that mapping, make the necessary improvements to satisfy the requirements in NORSOK S-002.

- Map the user-friendliness of the drilling systems to see which systems do not meet current requirements, including alarm requirements. What should be done to achieve systems that support the driller in his-her work?

- Review the alarm system, focusing on which functions the driller should handle, and what information is necessary in order to safeguard these functions.

Understanding risk

The responses from the drillers indicate that most feel their own understanding of risk is good. As work supervisors, the drillers also believe that they are able to ensure that the personnel working for them have a good understanding of risk. Risk understanding on the part of employees in the service companies is also perceived as being good, although the responses here show a somewhat lower score.

An important follow-up question to which the survey does not provide a clear answer is what drillers include in the term “understanding of risk.” Is it a clear understanding of the entire risk picture, both the risk associated with the work taking place on the drill floor and the risk associated with the operation down in the well?

One reason to question drillers’ understanding of risk is that the results of the survey show that more than 20% report they often do not have time to carry out a safe job analysis (SJA). Some drillers also say that SJAs do not help to bring attention to what is important for implementing a safe operation.

Meetings, planning, communication

Several respondents consider the departure meetings to be too general. In their responses, some companies have commented that they are intended to be general. Other companies want to do something about the departure meetings to make them more relevant for the drillers.

One third of drillers responded they did not always receive necessary information in the shift meetings and 45% experienced that there was not enough time to review the work descriptions in the shift meetings. An overview of the situation and work to be done is important for drillers to have an understanding of the risk associated with the work.

Three quarters of drillers often implement “prejob meetings” before each individual job. Nearly all drillers believe that these meetings often contribute to the safe execution of the job.

Training

A third of drillers say there is little support for updating their professional expertise. Often, the training they do receive is unrelated to the jobs they actually do. In most the drilling companies, there were three areas for improvement highlighted by drillers:

- Simulator training (beyond training in pressure-control simulator).

- Seminars in which the team trains together.

- Courses related to professional disciplines.

The degree of training and follow-up of new employees varies among companies. About one third of drillers state they rarely receive training in local conditions when they arrive on a new facility and only half say that they have a 1-week overlap on new facilities.

Companies proposed several training-related measures:

- Give personnel an opportunity to work as extra personnel in connection with promotions. This will provide better training prior to starting a new job.

- Consider facilitating a 1-week overlap in connection with transfers to a new unit.

- Review of existing internal mentor arrangement. Examine training and course matrix, transfer of experience, and attitudes.

- Arrange well integrity seminars four times/year; include all drillers in these seminars.

- Offer e-training course in “downhole understanding” to all drillers.

General questions

Only the four largest companies have submitted information regarding the general questions. The survey shows that 74 of 144 drillers have felt insecure on one or more occasions due to critical conditions during drilling operations in the last 12 months. Of these, as many as 9 drillers have felt insecure on more than 6 occasions. Insecurity on the job can entail considerable mental strain.

Workday

The driller’s work is complex, including many demanding tasks while monitoring a well. The driller supervises work on the drill floor and helps create an understanding of the risks. The working day is characterized by interruptions and the work requires continuous decision-making. At the same time, the driller must handle a large amount of information and complex screen displays. The survey indicates that there are areas in need of improvement so that drillers can manage risk and perform work safely.

Several significant framework conditions have emerged in the survey:

• Expectations for the driller position. About half of drillers feel that they have too many tasks. A fourth of drillers state that they sometimes work so hard they push the limit of what is prudent. Only a few feel that they have sufficient time and resources to function as a work supervisor.

In connection with reporting subsequent to audits, the PSA questioned whether distribution of tasks and responsibilities in drilling is clearly defined.

Some companies have proposed training assistant drillers to provide more relief for drillers. Solutions related to roles and responsibilities in this context vary from company to company.

Most drillers experience that, from time to time, there are too many administrative systems and procedures for them to deal with. Nearly half experience that the work programs are difficult to understand. This may be linked to time pressure, but the quality and user-friendliness of the procedures and the work program are probably also contributing factors. The quality of the content and execution of the drilling program, daily work program, and safe job analyses are key elements in understanding the risk scenario.

During audits, the PSA has seen that procedures do not always cover the activity that takes place. These are critical factors in the need for a good understanding of the overall risk.

Half the drillers who responded to the general questions stated they have felt insecure one or more times due to critical conditions during drilling operations during the last 12 months. This may be the result of limited capacity to handle requirements and roles, simultaneous work operations and the impact of external stress factors.

• Competence, understanding of risk. One third of drillers feel that they are given few opportunities to update their professional expertise. These drillers said the training they receive is not very well adapted to the job they actually do, including their job as supervisor. Several drillers state they receive little training in local conditions when they arrive at a new facility. In addition, many experience deficient training and drills with the rest of the crew.

Drillers state that they have a good understanding of risk. Nevertheless, the feedback indicates that there are problems associated with the value of the SJA, use of procedures, understanding of the drilling program, as well as training and workloads.

Therefore, there are reasons to question the drilling crew’s actual opportunity to obtain an adequate picture of risk.

• Physical design. Fewer than half the drillers are satisfied with the physical design of the driller’s cabin. At the same time, half the drillers report they have muscle pain and eye ailments. One risk factor that emerges in the survey is that a fourth experience reduced visibility from the driller’s cabin.

A third of drillers state that they sometimes lose concentration when sitting in the chair and have trouble staying awake on the job. This may be linked to many drillers feeling they receive insufficient relief.

Nearly half of drillers feel that there is too much information on the screen displays and too many alarms to deal with. This contributes to drillers’ perception that the drilling system provides inadequate support for their job performance in critical situations.

Continued work

The responses from the questionnaire survey indicate that weaknesses exist in both the human, organizational, and technical arenas, and in the interplay among them. The PSA hopes that the survey results will contribute to improving driller’s work and provide good experience transfer within the industry.

The Norwegian drilling contractors have initiated various follow-up activities to improvement systems and conditions. Some companies are still in the planning phase, while others have made substantial progress in proposing and implementing measures. Some proposed measures emerge in the report, while others were presented at the seminar in 2007.5

References

- Petroleumstilsnyet-Petroleum Safety Authority Norway, www.ptil.no.

- “Human Factors in drilling and well operations—The Drillers’ work situation,” January 2008, www.ptil.no [English and Norwegian].

- “Human Factors in the control room—an audit method,” PTIL, 2003, www.ptil.no/NR/rdonlyres/8AECF9B8-BCC9-43E6-A11D-8438340AE696/0/NorskHFRM.pdf.

- “YA-710—Principles for designing alarm systems,” PTIL, 2001, http://www.ptil.no/regelverk/R2002/ALARM_SYSTEM_DESIGN_N.HTM.

- Presentations (in Norwegian), www.ptil.no.