Firms can avoid EITI, FCPA pitfalls

In May, the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI) published the “EITI Business Guide” to encourage oil and gas companies, as well as companies in other extractive industries, to support implementation of the EITI in countries that are developing or operating oil and gas assets.1

The purpose of the EITI is to publish government revenues generated by extractive industries and to compare those revenues with payments reported by private companies in order to improve transparency in countries rich in oil, gas, and mineral resources. It is hoped that making this data public will allow in-country civil society organizations to hold their governments accountable for any discrepancies, which in turn should minimize corruption in the countries that adopt the EITI.

Although no country is required to participate in the EITI, once a country adopts the transparency initiative, all companies purchasing that country’s extracted resources typically are required to comply with EITI standards regarding transparency unless the individual country makes participation voluntary.

The EITI seeks to achieve transparency by requiring that government revenues from extraction industries and company payments for those resources be published in independently verified reports. Payments and revenues are then “reconciled by a credible, independent administrator, applying international auditing standards,” and the administrator’s opinion regarding that reconciliation, including any discrepancies, is published.

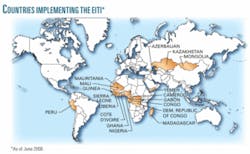

Currently, companies in 23 countries are subject to EITI requirements. Of these, 16 are in Africa: Cameroon, Congo, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Cote D’Ivoire, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, Ghana, Guinea, Liberia, Madagascar, Mali, Mauritania, Niger, Nigeria, Sao Tome and Principe, and Sierra Leone. The remaining countries are Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Mongolia, Peru, Timor-Leste, and Yemen (see map).

In many of these countries, adoption of the EITI is at its initial stages. Active involvement by oil and gas companies in the implementation of the EITI thus may help to decrease the risk of possible liability that can attach to oil and gas companies required to participate in the in-country programs. Although participation in the EITI creates neither legal rights nor obligations, because EITI requirements might result in companies’ publicly revealing their payment streams country-by-country, companies may be subject to liability relating to those disclosures, including for breach of existing confidentiality agreements or under the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (FCPA). Oil and gas companies offering to cooperate in EITI implementation, as the EITI Business Guide encourages, should be aware of both the potential legal risks they face and how to minimize them.

What is the EITI?

The EITI is a global initiative launched in 2002 to promote transparency in governments of countries that are rich in oil, gas, or minerals, which over time, “can assist in minimi[z]ing corruption in extractive industries” and “lead to improved public accountability and political stability.” The purpose of the EITI is to hold countries with underdeveloped economies accountable for revenues received from the sale of their countries’ natural resources. By ensuring that reported revenues match up with reported payments, the EITI hopes to prevent corrupt governments from skimming income off the top of these revenues for their own personal gains. However, if a discrepancy is identified, the companies making the payments, not just the countries receiving them, may come under legal scrutiny.

As stated in the EITI Business Guide, “[T]here is no international EITI policy or requirement” on how data on country revenue streams and on company payment streams reported to the independent administrator is to be published. Revenue and payment reporting may be published on an aggregated or disaggregated basis. Aggregated disclosure requires publication of a single number for each benefit stream, while disaggregated disclosure calls for publication of the overall number broken down by company. Whether a country chooses to publish its data on an aggregated or disaggregated basis ultimately may affect the particular areas of legal liability to which a company is exposed.

Avoiding EITI liability

Oil and gas companies participating in the EITI may trigger breaches of confidentiality agreements or FCPA scrutiny:

Breach of Confidentiality Agreements. Companies subject to the EITI may find themselves in breach of contract if the financial information they disclose to the independent administrator for reconciliation is the subject of confidentiality provisions in licenses or agreements with providers of service or goods or with the country itself. A typical confidentiality agreement in the context of the EITI would prevent oil and gas companies from disclosing to third parties any information concerning the terms of a particular arrangement that a company has to develop oil or gas resources in the host country. However, by disclosing payment streams to the independent administrator, oil and gas companies may find themselves in breach of such a confidentiality provision. This potential problem can be remedied if the EITI is implemented in accordance with the EITI Principles, one of which recognizes that “achievement of greater transparency must be set in the context of respect for contracts and laws.” As the EITI Business Guide reports, “If confidentiality clauses prevent companies from publishing commercially sensitive information, the government [adopting the EITI] must provide a clear and unambiguous indication to each company...that the clause does not apply in the case of EITI implementation.”

Three countries that have adopted the EITI, Nigeria, Kazakhstan, and Azerbaijan, deal with this issue in different ways. In Nigeria, the NEITI Bill “void[s] gagging clauses in license agreements [thereby] enabling disclosure of key disaggregated financial data as is required by law....”2

Conversely, in Kazakhstan, a memorandum of understanding (MOU) signed by all stakeholders in the EITI authorizes a company operating in the country’s extractive industries to refuse to submit its payment reports under the EITI guidelines unless the company determines “such disclosure will not contravene any of its own or its affiliates’, partners’, or contractors’ obligations to preserve confidentiality or similar obligations.”

Another approach, different from those of Nigeria and Kazakhstan, is that of Azerbaijan. According to a case study described in the EITI Business Guide, in Azerbaijan, concern about company confidentiality clauses has resulted in data being published on an aggregated basis, so confidential company details cannot be disclosed to the public.

Regardless of which approach is used, prior to disclosing any payment information under the EITI, companies should avoid liability for breach of contract or confidentiality agreements by ensuring that they have written permission to use confidential information covered by existing confidentiality clauses. They also should obtain written permission for EITI disclosures prior to entering any new contracts having confidentiality clauses.

Foreign Corrupt Practices Act. Oil and gas companies also should consider how to minimize their FCPA exposure during participation in the EITI. The FCPA consists of two sets of provisions:

- Antibribery provisions under 15 USC § 78dd-1(a), which prohibit payment of anything of value to a foreign official for purposes of securing business.

- Accounting provisions in 15 USC § 78m(b), which require companies to maintain certain recordkeeping standards and internal accounting controls to allow enforcement when bribes are not disclosed in financial statements and to counteract accounting devices that hide the existence of bribery payments.

The US Department of Justice (DOJ) has criminal enforcement authority for these provisions, and the US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) has civil enforcement authority.

The publication of data under the EITI is not itself a violation of the FCPA. However, information that is published by the independent administrator reporting any discrepancies between company payments and host government revenues may trigger FCPA scrutiny into oil and gas companies that disclose their payment streams through the EITI.

Discrepancies may be a result of accounting conversions (the EITI requires reporting on a cash basis rather than on an accrual basis, which most companies use), or other completely innocent reasons such as differences in international accounting standards. Typically, companies are given an opportunity to address discrepancies, but absent an MOU precluding disclosure of certain discrepancies, the country’s EITI report may reveal unexplained discrepancies between company payments and country revenue from that company. For example, in the Nigeria EITI report, discrepancies were reported even when the companies had not signed off on the discrepancy analysis.3 Although bribes are not always included in financial statements of the company or the country, such discrepancies can be a red flag for agencies investigating bribery under the FCPA. An investigation could be very time consuming, possibly tarnish a company’s reputation, and even result in a class-action or derivative lawsuit by the company’s shareholders.

The interest of the securities plaintiff’s bar may be increased by the recent introduction of a bill in Congress that would require the SEC to impose EITI-like disclosures “for the benefit of shareholders” on all foreign and domestic companies listed by the SEC. Unlike EITI disclosures required by countries selling their natural resource, however, under this bill there would be no reconciliation with revenues reported by countries, since the SEC has no jurisdiction over foreign sovereigns.4

Another recently introduced bill would allow a plaintiff to sue a foreign concern for antitrust-type violations, including treble damages, when the company has violated the FCPA and the plaintiff can show that it lost business as a result.5

Global cooperation

A recent increase in international cooperation enhances the risk that EITI discrepancies may come to the attention of the DOJ or the SEC. The UN Convention Against Corruption calls for international cooperation to facilitate enforcement of corruption-related offenses, and the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) Convention on Combating Bribery requires developed countries to work in a coordinated manner to criminalize the bribery of foreign public officials.

Although no country currently implementing the EITI has signed onto the OECD convention, all but four EITI countries (the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Equatorial Guinea, Kazakhstan, and Niger) have signed or ratified the UN convention. In addition, many multinational companies may be subject to investigation under these conventions through their international operations. Indeed, recent FCPA cases have involved concurrent bribery investigations by law enforcement agencies in multiple countries.

For example, Shell Oil currently is under investigation by the DOJ and the SEC for its operations in Nigeria, a country that has adopted and implemented the EITI. US investigators are also collaborating with the Economic and Financial Crimes Commission in Nigeria in that investigation. The investigation focuses on Shell Oil’s use of Panalpina, a Swiss freight firm that came under scrutiny in connection with Vetco Gray’s self-disclosed FCPA issue, which settled in February 2007.

The investigation of Shell Oil is just the latest in a string of FCPA investigations in Nigeria. There is no evidence that the EITI triggered this series of investigations; the Panalpina investigations were most likely triggered by Vetco Gray’s self-reporting of FCPA problems relating to bribes paid through “a major international freight forwarding and customs clearance company” thought to be Panalpina. However, payment discrepancies could increase FCPA scrutiny of certain companies or certain countries.

Nigeria was the first country to sign up for the EITI, and the Nigeria Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (NEITI) is a recognized leader in implementing EITI objectives. The NEITI calls for the publication, on a disaggregated basis, of “any information concerning the revenue of the Federal Government from [all] extractive industry companies, as it may consider necessary.” As such, in the audit report for 1999-2004, published in late 2006, the NEITI not only reported that there was a net difference of $7.9 million between payments reported by the extractive industry and revenues reported by the Nigerian government but also broke down the discrepancies by company. In particular, Shell failed to report $1.35 million that the Nigerian government reported it received. In addition to this financial audit of payments made by oil companies and revenues received by the government, to enhance transparency, the NEITI assessment included a physical audit of oil output, exports, and domestic consumption and a process audit looking at operations and procedures in terms of financial management and joint venture procurement.

Aggregated data best

In order to minimize being subject to an FCPA investigation because of discrepancies in a company’s payments and a host government’s revenues as published in a country’s EITI audit report, when a host government implements the EITI, extractive industry companies should insist that data be published on an aggregated basis.

According to the EITI Business Guide, “[c]ountries will ultimately adopt the level of disclosure with which the majority of stakeholders are comfortable.” Therefore, although the host government and civil society may prefer publication of disaggregated data to enhance transparency, if companies are vocal enough, a country may call for publication of only aggregated data.

Of course, even if an oil and gas company is successful in achieving publication of only aggregated data, the publication of aggregated data will not eliminate the risk of an FCPA investigation entirely. Large discrepancies in aggregated data may cause law enforcement to look more closely at international companies operating in those countries.

Even if only aggregated data is to be published, oil and gas companies should try to avoid the possibility that the country will unilaterally disclose disaggregated data. According to the EITI Business Guide, “more data [may] be made publicly available on a disaggregated basiseven if this is not required by the EITI process.” Although the EITI Business Guide provides an example of a company’s going beyond the EITI requirements and voluntarily publishing information on its payments to the host government on its public website, it is also possible that the host government itself may choose to publish data about specific payments it received from extractive industry companies. In order to avoid the disclosure of such information, when a host government implements the EITI, extractive industry companies should insist on provisions being included in the MOU that prevent the host country from publishing any information that does not appear in the independent administrator’s report.

Data protection

In addition, oil and gas companies should take steps to protect the data submitted to the independent administrator. Disaggregated data must be disclosed to the independent auditor to allow for company-by-company reconciliation. Once detailed company data is reported to the independent administrator, there is a possibility that such data may be disclosed if proper precautions are not taken. Companies therefore should take care that the independent administrator himself does not disclose financial data that could trigger an FCPA investigation. Oil and gas companies can do this by insisting on a provision in the MOU that requires the auditing firm responsible for auditing and reconciling the EITI reports to sign confidentiality agreements concerning the detailed reports submitted by the individual extractive industry companies.

For example, although the MOU signed by the government of Nigeria and the oil and gas companies in the country remains secret, a confidentiality agreement between the companies and the independent administrator was signed by each company in 2005. Additionally, the MOU signed by the government of Kazakhstan, the extractive industry companies, and the nongovernmental organizations of civil society includes a provision limiting the auditor’s ability to disclose information: “The audit company shall at all times keep the individual reports submitted by the Companies strictly confidential and shall not disclose or divulge these reports in whole or in part to any other Parties to the Memorandum, any third parties, or the public unless authorized by each submitting company.” Only by insisting that a similar statement be included in the MOU can extractive industry companies further minimize the risk that information will be disclosed that may trigger an FCPA investigation.

EITI good for business

According to the EITI Business Guide, an individual company may find it beneficial to participate in the EITI in order to demonstrate international credibility, deliver on business principles, and show industry leadership. And eliminating corruption is a laudable goal that will benefit foreign investors in the long run. As the recently proposed Extractive Industries Transparency Disclosure Act puts it, “[t]here is a growing consensus among oil, gas, and mining companies that transparency is good for business since it improves the business climate in which they work and fosters good governance and accountability.”

However, if the EITI is not implemented carefully, oil and gas companies may find themselves facing legal liability for breach of confidentiality agreements or increased scrutiny under the FCPA. Only by insisting on the waiver of confidentiality requirements, publication of aggregated revenue and payment streams, and inclusion in the MOU of provisions restricting disclosure of financial data by host governments and the independent administrator can extractive industry companies best minimize the risks of such liability.

The EITI announced in the Spring 2008 EITI Newsletter that the government of Iraq has formally committed itself to implementing the EITI. As the single largest country in terms of proven oil reserves to do so, and with so many companies extracting resources from the country, Iraq provides extractive industry companies with a prime opportunity to ensure that the EITI is implemented in a manner that both enhances transparency and protects the extractive industry companies from liability that may arise because of such transparency.

References

- The “EITI Business Guide” is available at http://eitransparency.org/document/businessguide.

- The NEITI’s “Handbook on Transparency & Reform in the Oil, Gas, & Solid Minerals Sectors” is available at http://www.neiti.org.ng/files-pdf/NEITI_Handbook4.pdf.

- The “Nigeria Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative Audit of the Period 1999-2004: Final Report” is available at http://www.neiti.org.ng/files-pdf/ExecutiveSummaryFinal-31Dec06.pdf.

- H.R. 6066, the Extractive Industries Transparency Disclosure Act, introduced on May 15, 2008, is available at http://www.house.gov/apps/list/press/financialsvcs_dem/frank_144_xml.pdf.

- H.R. 6188, the Foreign Business Bribery Prohibition Act of 2008, introduced on June 4, 2008, is available at http://www.govtrack.us/congress/billtext.xpd?bill=h110-6188.

The authors

Mara V.J. Senn ([email protected]) is a partner with the law firm Arnold & Porter. She is a member of the firm’s white collar and international arbitration groups and is the head of the international arbitration group’s Energy Committee.

Rachel Frankel ([email protected]) is a third-year law student at The George Washington University Law School. She also is an articles editor for The George Washington Law Review.