‘Silent disruption’ limiting oil supply

Recent increases in the price of oil result largely from a collision of demand growth with what might be called a “silent disruption” to worldwide supply.

Like past constrictions to the delivery of crude oil and oil products, the current phenomenon has raised prices as much by lowering expectations for future supply as by immediately removing physical volumes from the market. Unlike past disruptions, this one lowers expectations not by way of a single event, such as a war or natural disaster, but rather through a series of mostly geopolitical developments that together impede investment.

The combined effects of those developments, important among which is a surge in resource nationalism, have lowered expectations for global oil supply during 2005-10 by 2.5-4.5 million b/d (Download a PDF of the table).

The crude price

In 2008, the cost of crude oilcombined with federal and state taxeshas accounted for 90-93% of the price of gasoline at the pump in the US (based on West Texas Intermediate prices plus 50¢/gal of federal, state, and sales taxes).

So why are crude prices so high?

Over the last 10 years, the world oil market has clearly experienced an unprecedented number of new and sustained impediments to upstream development, including unilateral contract renegotiation, nationalization, lack of investment by national oil companies, restrictive access to resources, and war and civil strife.

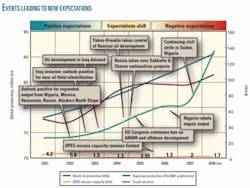

Many of these factors, along with technical challenges in bringing new oil fields online, have also reduced excess production capacity among members of the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries. At the same time, global oil demand has grown robustly (see figure).

When the events highlighted in the figure occur, not only does the world oil market lose existing production, but expectations on the availability of future supplies are revised downward.

A recent or perhaps recurring trend is resource nationalism, wherein host nations change the terms of their contracts with international oil companies (IOCs) that are developing indigenous oil and gas resources. Encouraged by the swift escalation of oil prices in recent years, this trend is now spreading rapidly. Venezuela’s 2007 nationalization plan led to a significant decline in investments and even the expulsion and banning of ExxonMobil from the country. Foreign direct investment in 2007 declined by about 50% compared with the yearly average during 2003-06. Rising oil prices have emboldened governments to take a greater share of the revenue of projects, agreements for which were negotiated when oil prices were substantially lower. Production at Kazakhstan’s 13 billion bbl Kashagan oil field was delayed for several years as the operators faced a series of technical obstacles. The delay in bringing the field into production was one of several reasons the Kazakh government gave for renegotiating the 2005 contract.

Many explanations for these actions are advanced, including that existing production contract terms do not permit a fair distribution of the good fortune of rising prices. Even in Canada and the US, investors are not immune from attempts by their respective legislative bodies to change previously agreed-upon contract terms.

Operating companies, with some notable exceptions, have had little choice but to accept these new terms to protect residual value in their projects as existing legal alternatives are either too cumbersome or present further risks to remaining operations in the host county.

The longer-term consequences of these unilateral actions are much more than a redistribution of revenue. These actions are likely to result in further reductions in investment in the exploration and development of petroleum resources, an arena in which there is a growing consensus that the industry is already “effort-constrained.”

Russia’s attempts at resource nationalism may have come at an inopportune time. Foreign investment has suffered over the past several years as its western fields are in decline. Output has now dropped for 5 months in a row, and strife at TNK-BP has intensified.

Projects that present relatively high technical thresholds, extraordinary project completion risks, and very long lead times to initial production may now be unable to attract adequate capital to go forward.

This trend in unilateral contract changes, combined with growing limitations on access to resource development, and in many cases unrealistic terms for new projects, is all adding to the so-called peak-oil problem, which is now more about constraints above the ground than below. In a kind of perfect storm of bad luck, the resurgence in resource nationalism has been supplemented by civil strife and armed conflicts in several important producing regions in the world.

The world oil market has been subject to considerably more turmoil than that generated by the resurgence in resource nationalismarmed attacks in Nigeria and Sudan are relevant examples of the rebel activity and civil strife that have caused and continue to bring to the world reduced oil market outputand more importantly, expectations that new opportunities to expand production must be postponed.

Role of expectations

Ultimately, prices in the world oil market are set by the fundamentals of supply and demand. However, crude oil prices at any given moment reflect a wide range of considerations that go well beyond immediate conditions in the market.

Important among these considerations are expectations about future conditions and events including world demand, technological advances, availability of skilled workers, accessibility of supplies, replacement cost of new supplies, technical and political risk, war, and terrorism, among others. In many cases, the immediate loss in output from any number of unexpected events has much less effect on the world market than the resulting shift in expectations about the ability to expand output over the next 5-10 years.

Major shifts in the price of crude oil since the early 1970s can be explained in part (perhaps largely) by major shifts in expectations about future output. For example, the important consequence of the 1973-74 Arab oil embargo was the structural shift in the ownership and control of the vast resources of the Persian Gulf region. The embargo, by changing expectations about future production levels from the major Middle East oil producers, brought about a sustained increase in the value of oil.

The second oil price shock, in 1979, can be seen in a similar light, as the Iranian revolution also sent a signal that the region was in for a period of instability and that the prior view that future output from Iran and Iraq would expand substantially was no longer likely. In both cases, prices were affected by changing expectations about future production levels.

The subsequent fall in oil prices in the mid-1980s can be linked to a fundamental shift in medium-term expectations about demand (as consuming countries engaged in fuel substitution and conservation) and to Saudi Arabia’s becoming no longer willing to restrict output to protect the price structure.

From the 1980s until the 1999 oil price recovery, OPEC was unable to limit (or had collectively been unwilling to agree to a strategy of limiting) sufficient volumes of oil production to obtain price levels that were substantially above long run replacement costs. Part of the problem with OPEC is that it collectively does not and cannot arrive at a consensus on long-term production strategy because of the divergent long-term interests of its membership.

Prices surge

Since mid-2004 the price of oil has risen dramatically as the world oil market also has faced a perfect storm of bad luck. Resource nationalism has run rampant, harming near-term output, and shifting expectations on future production.

World oil prices initially rose to $30/bbl from about $10/bbl.While this was substantially above the levels experienced in the 1990s, it reflected some combination of rising demand and increased difficulty in replacing reserves as producers moved to technically more challenging environments, having produced much of the “easy” oil. The supply outlook was generally positive, with output rising to keep pace with growing global demand.

Expectations about rising investment in oil and gas development in Nigeria, Russia, Sudan, Venezuela, the US, and many other places soon turned into an environment where projects were postponed, access to resources was denied or postponed, or contract terms were changed. Within a few years, an era of positive expectations during 2000-04 evolved into an era of negative expectations, and the bad news keeps on coming.

Superimposed on this supply situation have been rising incomes in China, India, and other parts of the developing world.

In these economies, too, demand is rising rapidly for middle distillates, particularly diesel fuel.

The figure and table show the forces that have brought about much of the shift in expectations about production. Note that by early 2005 historic forecasts of production growth by the US Energy Information Administration and others were unrealized. Combined with falling OPEC excess capacity, this shrinking of expectations about future production helped drive crude oil prices upward.

Effects of disruption

The oil market is highly integrated, and a disruption somewhere in the market is a disruption everywhere.

The silent disruption described here results not from a single event but from events at several production centers. This production is missing from the market, and the subsequent higher prices are imposing substantial costs on the US economy and US consumers.

In the period described in the figure as the “Era of positive expectations,” buyers and sellers reasonably expected that oil supplies would grow from major producing regions. These additions to output did not occur, largely because of problems above the ground and not below. The problems in the upstream market have been amplified by constraints in refining capacity (see sidebar).

Oil prices of course could be expected to rise in response to demand growth and the rising costs of new supplies. But current price increases reflect a failure of the world petroleum market to deliver new supplies from fields that could easily do so within the current (or even a lower) price structure.

US policies that have restricted opportunities to expand conventional supplies from Alaska and prospective offshore and onshore provinces in the Lower 48 have contributed to this high-price environment, along with civil strife in Nigeria, delays in new OPEC capacity, and resource nationalism in Venezuela.

Many observers have argued that these higher prices provide benefits in the forms of demand reduction, new conservation initiatives, and acceleration of incentives for moving the US to the fuels of the future. Whether this is a cost-effective approach for the US economy depends on whether current prices are in fact approaching the long-run backstop price: i.e., the price where alternative fuels, conservation, unconventional supplies, etc., are so plentiful that the price of oil can rise only modestly if at all.

Our perspective is that the current price structure is not sustainable. But failure to provide access to conventional fuels may mean the transition to a lower and more-realistic price level may also involve unnecessary economic pain.

This article is based on testimony presented to the Task Force on Competition Policy and Antitrust of the US House of Representatives Committee on Judiciary hearing on retail gasoline prices May 7, 2008.

The authors

Lucian (Lou) Pugliaresi ([email protected]) has been president of Energy Policy Research Foundation (EPRINC) since February 2007 and managed the transfer of its forerunner, Petroleum Industry Research Foundation Inc. (PIRINC), from New York to Washington, DC. He served on the board of trustees of PIRINC before assuming the presidency. Since leaving government service in 1989, Pugliaresi worked as a consultant on a wide range of domestic and international petroleum issues. His government service included posts at the National Security Council at the White House; Departments of State, Energy, and the Interior; and the Environmental Protection Agency.

Ben Montalbano ([email protected]) is a senior research analyst at EPRINC. He is a graduate of the University of Colorado at Boulder where he studied Economics. Montalbano joined EPRINC in January 2008 and earlier provided research support to the foundation during his college years, covering both world energy markets and oil and gas production developments. He speaks fluent Russian. In addition to his research efforts in the oil and gas market, he has worked in the information technology industry.