Residents of Iran’s north must surely have experienced chagrin at a visceral level in December 2007 when they froze after Turkmenistan halted natural gas exports to the country. Surely the irony was not lost that, even though Iran sits atop the world’s second largest gas reserves after Russia’s, it is beholden to Turkmenistan for imports supplying as much as 5% of its gas needs.

Turkmenistan cited pipeline issues as the cause of the gas curtailment, but most insiders believed that Turkmen authorities, who wanted price increases, were upset at payment delays and at Iran’s refusal to submit to the dynamics of the new pricing realities. Iran had paid Turkmenistan $75-140/1,000 cu m for its gas; however, the Turkmen leadership wanted its deliveries to reflect the new market. Under the new agreement, Turkmen gas will now cost $130/1,000 cu m until June 30, 2008, when the price will increase to $150/1,000 cu m.

While upwards of 40 million people endured frigid temperatures that plummeted to 4° to 30° C., Iran’s President Mahmoud Ahmedinejad darkly proclaimed that the gas halt was a conspiracy and done “at the behest of some domestic actors.” Domestic confidence crumbled with the government’s inability to meet its national gas needs without the Turkmen imports. How is it that a country with the world’s second largest gas reserves found itself in this perverse situation?

Huge gas reserves

Iran’s dilemma actually is common to many resource-rich countries. Iran’s gas reserves are intimidating28 trillion cu m (995 tcf). However, 62% of the reserves are in nonassociated fields that have not yet been fully prepared for investment. Given the growth of gas in the world energy market and the concordant development of the global LNG market, Iran’s oil and gas development should be at its peak like that of Qatar, its erstwhile rival and North field neighbor adjoining Iran’s South Pars field.

However this is not the case. Iran’s clerical leadership had set its sights on rapidly developing the country’s gas reserves even in the face of stringent opposition from the US and the United Nations. The deficiency of Iran’s gas development lies more with its internal economic policies than with external, international economic pressure. As the price of gas rises, Iran’s inability to secure investment and provide domestic energy for its citizens will be thrown into sharper relief. The conundrum revolves around the economic term of “perverse incentives” active in the gas sector, and to a certain extent played out in the gasoline arena.

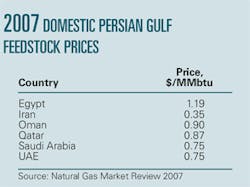

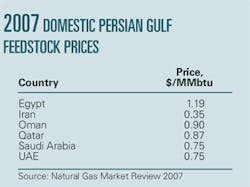

To soothe domestic discontent over its stagnant economy, Iran subsidizes domestic gas consumption at a rate of $0.35/MMbtu, which places its cost to domestic consumers at one of the lowest rates in the Middle East (see table).

This low price is a reason for the extreme difficulty the National Iranian Gas Co. (NIGC) has in seeking to monetize its large gas resources, especially those in offshore South Pars (see map).

The gas crunch is not unique to Iran; it occurs across the Persian Gulf as governments struggle to maintain their domestic pricing schemes and the stark gap between domestic and international prices. For example, the UAE is experiencing an electric power generation crisis because gas prices have increased more than tenfold in less than a decade, and further strain is expected as production costs are projected to soar by more than 100% in the next 2 years.

Last summer the UAE experienced such an acute gas shortageabout 1 bcfthat it was compelled to switch to crude oil and coal for power generation. Gulf governments are caught in the trilemma of needing to fuel domestic industrialization while providing inexpensive power in the face of increasing domestic demand for a populace that views cheap power as the essence of the social contract.

Nuclear energy

Nuclear energy appeared to be the best option to the quandary in which the gas-producing countries in the Persian Gulf found themselves when gas became unavailable and oil too valuable to be used for domestic power generationa nearly insoluble problem. The current Iranian nuclear program, even though of front page news concern to the international community, is not unique to the region when taken in proper focus.

For example, Egypt is pursuing its own nuclear energy vision, with President Mubarak’s lauding the national goal to build six 2,000-Mw nuclear reactors, and in 2006 the six-nation Gulf Cooperation Council released plans to develop a comprehensive nuclear energy program for the region.

This year French President Nicolas Sarkozy traveled to the UAE to finalize a deal that will give Total SA permission to join forces with the reactor-designer Areva and the utility company Suez to build nuclear power stations within the UAE. This indicates that Iran’s Bushear nuclear plant, built with Russian support, is not necessarily an aggressive step towards nuclear weapon proliferation in the region but could likely be the blowback from a misguided energy policy symptomatic of many energy-producing countries.

The crisis with Turkmenistan challenged Iran’s status as a stable gas supplier. With the European Union’s fear of a Kremlin-dominated Gazprom and gas diversification as a high priority, many EU countries may be willing to gamble on an Iranian supply of gas. By 2030, it is estimated that Europe will depend on foreign suppliers for as much as 85% of its gas supply, quite a jump from the current 55%.

Possible reinvigoration

Iran, with its large reserves, presents a very attractive option because energy needs and supply diversification may trump current geopolitical issues connected with Iran’s nuclear ambitions. Iranian gas could find a place in the EU energy security mix. Even though current international sanctions and internal technical and political problems have hindered both gas production and the development of Iran’s energy industry, potential investment from Europe could reinvigorate Iran’s energy sector.

Portugal has been holding negotiations with Iran since 2006, and Italian-based Edison is discussing possible Iranian gas sales to the Italian market. Meanwhile, Austria’s EconGas GMBH signed a gas supply agreement for Iran to begin deliveries in 2013.

Austria’s OMV planned to develop Iran’s South Pars gas field for the planned Nabucco pipeline, but the marked tension between the US and Iran prompted OMV to turn instead to negotiations with Azerbaijan.

As a further reflection of the increased US pressure on international oil companies (IOCs) operating in Iran, Shell and Repsol are negotiating to leave the $10 billion gas project planned for Block 14 in South Pars field. Unwilling to fully sever the energy umbilical cord, these two companies want to reserve the right to return and bid on future blocks if and when US-Iranian relations improve.

By far, Iran’s largest investment contract was with the Swiss company, Elektrizitaets-Gesellschaft Laufenburg (EGL), which signed a 25-year contract with NIGC Mar. 17 for gas supplies valued at €18-27 billion ($28-42 billion) over the contractual life. This deal anticipates the delivery of 5.5 billion cu m/year of gas to Europe. The final value of the agreementwhich depends on the evolving price of gas over the coming yearsis structured to provide a fourth avenue for gas to enter Western Europe apart from Russia, the North Sea, and North Africa. The anticipated route is from Turkey through Greece and Albania. For the gas to reach Italy, a pipeline may be constructed under the Adriatic Sea in 2010.

EGL has concluded final negotiations with possible partners, and this summer it anticipates public announcements of the pipeline construction partners. The pipelinewhich is expected to begin operations in 2012will connect existing gas supply chains in Greece with those in Italy.

When the EGL deal was announced, the US vigorously protested it, vowing to review it for possible violations of the Iran Sanctions Act. However, Joachim Conrad, who heads EGL, brushed aside concerns on the grounds that Europe’s long-term energy security is more important than short-term political disagreements. Swiss Foreign Minister Micheline Calmy-Rey also argued that the deal did not violate the Iran Sanctions Act.

Placed in the broader context, Iran is merely one prong in the EU’s multipronged strategy to achieve gas diversification. The “Iran card” allows the EU to exercise leverage with Gazprom ahead of 2010, when many major gas supply contracts are slated to be renegotiated. The EGL deal dramatizes the attractiveness of Iranian gas, assessed at €90-200/1,000 cu m, compared with Gazprom gas at €240/1,000 cu mwhich may increase to €260 at yearend.

Iran doubtlessly provides a useful counterweight to Gazprom’s singular influence over the EU’s gas supply. On the most practical basis, there is no other viable supplier for the EU from the fourth corridor. Potential gas volumes from Azerbaijan cannot support the deliveries needed. And developing gas fields from Iraqi Kurdistan or obtaining associated gas from the northern Iraqi oil fields are illusory stratagems until the security situation improves and the political dispute between the central and regional authorities finds a solution, which may not be any time soon.

Stable Iran supply?

The persistent question, however, is whether Iran will be a stable supplier. It has curtailed gas shipments to Turkey twice, initially in 2006 and again earlier this year when Turkmenistan ceased shipments to Iran. In December 2006 Turkmenistan stopped supplies until a new gas pricing agreement could be concluded. As a result of the 2008 Turkmen cutoff, Iran cut shipments to Turkey by 75%, reducing them to 5 million cu m from 20 million cu m.

The Turkmenistan cutoff to Iran had a ripple effect, causing Ankara to dip into its stored supply by a third and Turkey to further cut off Azeri shipments transiting to Greece. This halt came at an unfortunate moment for Turkey, which experienced a stellar jump in consumption due to the unusually cold weather.

Granted, the issue behind Iran’s stoppage did not seem political in nature as did the Russia-Ukraine gas crisis. However, there is a very real possibility that if Iran and Turkmenistan bicker, Turkey and the EU will suffer the consequences. And judging from the past, it appears that in order to encourage agreement, Turkmenistan will resort to gas reductions at the peak of winter to encourage compliance.

Turkmenistan’s current strategy is to modify the 2006 price schedule with Iran that stipulates an increase in gas exports of up to 14 billion cu m/year from the base volume of 8 billion cu m/year. With tremendous momentum from its successful price renegotiations with Gazprom and PetroChina, and enjoying the rising price from the Asian market, Turkmenistan was emboldened to press Iran for the price increases.

The latest Iran-Turkmenistan price dispute raises questions about the proposed $7.5 billion, 3,000 km Nabucco pipeline, construction of which is expected to begin in 2010. Nabucco, if constructed, will allow Iranian gas to flow through pipelines from eastern Turkey to Austria’s Baumgarten gas hub, via Bulgaria, Romania, and Hungary, and transport some 30 billion cu m/year of gas.

However, the fear is that an export halt anywhere along the gas line could affect the entire network and prompt each participating country to hoard gas for its domestic consumers. Even though Moscow and Tehran are allies in many areas, the scramble for the EU market whets Gazprom’s desire to frustrate an Iranian attempt to enter the EU market.

The Nabucco negotiations, which encouraged Russia to step up support for the South Stream pipeline, show the potential for Iranian gas to disrupt the energy balance of power in the region.

Price liberalization

For Iran to truly reach its potential and become a stable supplier for the EU, price liberalization must bring sufficient investment into the gas industry. Leaving aside for a moment the political pressures from the US and UN Security Council, gas and oil power are too cheap in Iran.

Its clerical leadership is politically divided as to how best to exploit its gas resources. Part of the leadership contends that the gas should be used primarily for oil field reinjection to take advantage of high oil prices; another group believes that gas should fuel the domestic market at prices below market to encourage industrial development and provide low domestic energy prices to the populace; while a third group says Iran should emulate Qatar and develop its gas and LNG more actively for export.

As this article goes to press there is no clear winner in this dispute, and it appears that in making concessions to each viewpoint, Iran is incorporating all of them. However, if another gas shortage occurs, populist calls will be strong to halt any gas export or LNG programs. Herein lies the danger of relying on Iranian gas.

The Iranian domestic gas market will probably experience some minor price liberalization in the near-to-midterm. The nation’s budgetary strains from supporting domestic consumption are beginning to unravel the economy. The June 2007 riots, which started from the government’s decision to ration gasoline while increasing the price, proved that the leadership must tread carefully. In the past, the commercial and political costs of producing gas for domestic power generation were slight, and it could be contended that the best possible use of domestic energy was to encourage industrialization and provide cheap energy.

But current conditions are quite different; there is a very real opportunity cost for providing extra gas for domestic power generation at below market rates as opposed to supplying the international market. Additional gas production requires major investment in an industry that faces great cost increases and that demands increased technical skill.

Additional gas sold to international buyers in the EU rather than to domestic consumers will yield a much higher return under the current pricing scheme. Iran’s uranium enrichment activities likely will chill some foreign investment, as shown by the fact that OMV, Shell, and Repsol moved away from the Iranian blocks. But the EGL deal suggests that long-term energy security ultimately will trump the political debate.

South Pars field offers investment bargains to IOCs. Since gas, rather than oil, is one of the last provinces where IOCs retain technological dominance and the ability to achieve contractual leverage, South Pars eventually will experience increased investment.

However, as Turkmenistan and Gazprom have shown, market-based pricing is the future, as is the reality that rate hikes will be passed down the line. The Iran-Turkmenistan pricing dispute shows the growing clout and confidence of the Central Asian gas producers. Burdened with its subsidized internal market, Iran has no real choice but to recognize these artificially low domestic gas prices as perverse incentives that create chaos in the domestic economy and feed an unrealistic thirst for cheap energy in the citizenry.

Of course, raising gas prices in the face of rapid inflation and record unemployment will be a difficult maneuver, but history has shown that if proactive stratagems are taken, worse case scenarios, which might include domino-like chains of events, can sometimes be avoided.

The author

Justin Dargin is a research fellow at Harvard University where he researches energy policy in the Persian Gulf region. Specializing in international law and energy law, he is a prolific author on energy affairs. He is a cofounder and director of the nonprofit International Institute of Ideas (Interintel), which seeks to address the concerns of global energy poverty and sustainable development by providing developing communities access to inexpensive energy supplies. During his graduate legal studies, Dargin interned in the legal department at the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries, where he advised senior staff on the implications of European Union and American law in multilateral relations. Dargin also was a researcher at the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies, where he studied Middle East gas issues, and pioneered a substantive work on transnational gas trade in the form of the Dolphin Project. Dargin holds a BBA in management and information systems from University of Michigan and a JD degree from Michigan State University. Fluent in Spanish, English, and Arabic, Dargin also has been active in energy issues involving Latin America and the Middle East.