COMMENT: US can learn from European experience with cap and trade

Cap-and-trade responses to climate change are in place in Europe and are in prospect in the US. All US presidential candidates believe climate change is a man-made problem that can be solved by reducing emissions of greenhouse gases (GHG). Before adopting a cap-and-trade system, the US should look closely at the European experience.

Under a federal cap and trade, the government sets a limit or cap on GHG emissions as a lower percentage of current emissions, and allowances are distributedeither for free or through an auctionto emitting parties. They report all emissions, and at the end of a compliance periodsay, 3 or 5 yearsthey surrender allowances equivalent to their actual emissions during the period. Any party failing to do so will be fined and required to achieve reductions in the next period.

The rationale is that, under such a system, any emitting party has an incentive to cut emissions to the level where the marginal price of reductions is equal to, or higher than, the cost of allowances on the market. As a result, emissions would be cut most where it is cheapest to do so and the lower the cap, the higher the price of emissions quotas.

Cap and trade systems have been applied successfully several times in the past, including in the US under the Environmental Protection Agency’s acid rain program aimed at reducing sulfur dioxide (SO2) emissions.

There is, however, some evidence that containing GHGs would differ from controlling SO2 because, among other reasons, virtually every industrial plant and living being emits CO2. Controlling emissions implies either a transaction cost so high that the whole system would be unsustainable or a wide degree of political arbitrariness.

The EU trading system

In 2005, the last year for which official data are available, emissions from the first 15 members of the European Union (EU15) were lower than those of 1990 by 1.5%, at the same levels as 1992, and higher than those of 2000. The year 2005 was also the first year Europe’s cap and trade mechanism, the Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS), became effective. The EU was targeting the Kyoto Protocol’s goal of cutting emissions by 8% below those of the baseline year at least since 2003, when a directive established the ETS.

Before 2005, no Europe-wide policy had been established, but individual member states were aware of the targets and had implemented various policies uncoordinated with other EU states, with the goal of getting closer to their emission-reduction goals. Moreover, at least since 2004, a secondary market for emissions arose, with a small but growing trading of emissions futures.

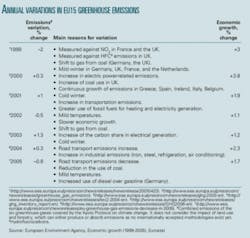

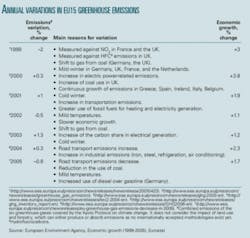

The table reports the yearly variations declared by the European Environment Agency (EEA) together with explanations the agency has supplied in its annual communiqués to explain the changes. Except for 1999, the variation is never attributed to specific policies. In 5 years out of 7, a significant role is attributed to climate conditionsthat is, to a factor completely exogenous and which cannot be politically controlled. Then, on and off, the greater or lesser use of coal in the mix is noted, and that mix depends both on industrial choices or long-term policies, and on demand, which in turn depends primarily on the temperature and on economic growth (or lack thereof).

It is therefore not an exaggeration to state that if Europe gets more or less close to the Kyoto target, it will depend largely on variables that are independent from climate policies; indeed the single most important variable will be...the weather: the warmer it is, especially in winter, the lower the emissions will be.

The very analyses of the agency therefore show that regardless of the cost, European policies are ineffective, thus inefficient. In fact, while emissions data are made available with a 2-year delay, verified emissions data related to the ETS sectors are more quickly available, so it is already possible to draw preliminary conclusions.

Phased emissions rights

Before the failure of European policies is assessed, a closer look at the European market for emissions rights is needed.

The ETS was created with a directive in 2003, and enforcement began on Jan. 1, 2005. The ETS identifies two phases of application: a first pilot phase during 2005-07 followed by a second momentum phase in 2008-12 that will coincide with the Kyoto Protocol applications period during which companies and countries are called upon to meet the objective of reducing emissions by 8% below 1990 levels.

At the beginning of each phase, a certain number of emissions permits is gratuitously assigned to firms covered by the ETS. Distribution of the permits takes place according to a national allocation plan by which each member state declares the total amount of the emission quotas that it intends to distribute within its state. On Apr. 30 of each year, the plant will have to return a number of permits equal to its emissions. If it is unable to do so, or if it did not have a way to buy the extra needed quotas on the market, it must pay a fine of €40/tonne of CO2 equivalent emitted above its allotted permit amount in the first phase and €100/tonne for unpermitted overage in the second phase.

The first phase covers only CO2, while in the second, the other greenhouse gases identified by the Kyoto Protocol come into play.1 Once the fine has been paid, the company is not exempted from cutting its emissions, so the €40 and €100 fines respectively do not work as a cap on carbon price. Finally, the directive does not allow the banking of allowances and their transfer from one phase to another. If the enterprise that holds excess emission quotas cannot sell them in useful time, their value crumbles to zero.

From this summary description, the three main elements of political arbitrariness of the ETS project emerge: the inclusion of some industries and not others, the prohibition against banking the permits, and their gratuitous distribution at the beginning of each phase on the basis of the historical emission record in a reference periodthe so-called grandfathering.2

Furthermore, the albeit small experience accumulated by ETS gives rise to perplexities about how well it is operating, with particular regard to the high volatility of the carbon allowance price. The price of the allowances, which at the beginning of the market increased from the initial €7/tonne to settle at around €20-25/tonne, suddenly crashed. The crash coincided with the publication of the data on emissions by the ETS industries. The price then shot up again to more than €20/tonne at the beginning of 2008 and the beginning of the second phase, and as this article is written, a tonne of CO2 is traded at or above €25. The immediate growth reflects the prohibition against banking excess permits, which couldn’t be transferred to 2008-12.

What caused the price volatility, which has effectively nullified the predictable cost of the quota system? According to a Bologna University Working Paper by Stefano Clô, a phenomenon of “over-allocation” in favor of the ETS industries has taken place. The national allocation plans approved by the Commission for 2008-12 reflect a sensitivity to these issues. For example, Brussels issued 1,439 permits vs. the 1,570 requested. But thisand, in junction the prices of quotas, which went back to pre-2006 levelsallows one to predict that the second phase will have tangible costs for the enterprises and consequently for consumers.

The observation about the system’s high level of inefficiency as a whole must be added to the need for equity and the need to set up a system of rules that is certain and stablea need made cogent by the size of the objectives and by the short time span in which they should be reached. Verified emissions data reveal that emissions from ETS industries in 2007 were higher than those in 2006 by more than 1%.

The new directive

The European Commission is aware of all these criticisms, but it finds itself locked in by commitments made perhaps too lightly. So in recent months, it has been working intensely, rewriting former decisions. This has culminated in the change of the objective of renewable resources from 20% of primary energy consumption to 20% of final consumptionalthough the Orwellian effort to rewrite past decisions prevented the European Commission from stating it openly.

The new directive introduces substantial changes, some of which are questionable. Its greatest flaw is in the zone of uncertainty, which the directive says it wants to eliminate but which is instead amplified.

Beyond the statements of principle, which change nothing, the directive immediately sets fair general objectives, such as harmonizing the emission market and creating maximum predictability and stability of choices.3

Furthermore, it is honestly recognized that “the environmental outcome of the first phase of the EU ETS could have been more significant but was limited due to excessive allocation of allowances in some member states and some sectors.”4

The new directive foresees the extension of the ETS to other emitting plants or industries for which it is possible to monitor emissions.5 The directive proposal suggests superseding multiple national allocation plans with the adoption of a single unified, communitarian cap to reach within a time period longer than the 5 years of the first two phases.

The other fundamental choice concerning the third phase is about passage from grandfathering to auctioning in the allocation of quotas to guarantee the “efficiency of the ETS, transparency and simplicity of the system, and [avoidance of] undesirable distributional effects.”6

Thus, starting from 2013, all quotas for the thermoelectric industry will be allocated through auctions. This choice seems in line with the preferences of most economists, who recognize two advantages in allocation through quota auctioning: less exposure to political whim and the ability to generate tax income.7

This last point is open to interpretation; it is not certain that a larger flow of resources to public finances can be considered advantageous, from both the environmental perspective and that of proper market operationin fact, the opposite is more likely.

The first argument about the greater neutrality of auctioning seems to have better foundations, but further reading of the European directive on emission trading indicates that exceptions seem far more numerous than the cases to which the presumed rule applies.

One line after stating that allocation for the thermoelectric industry is to be performed through auctioning from 2013 on, the report adds that, “in order to encourage a more efficient generation of electricity, electricity generators could, however, receive free allowances for heat delivered to district heating or industrial installations.”8

For all other industries, several factors will influence the passage from free distribution to auctioning, which will take place gradually.

Enterprises are then told that a variable allowances quota will be distributed free of charge. The quota will differ from industry to industry and from year to year, and within the same industry in a given year, it will change from case to case.

And there is more: if the other industrialized countries do not commit to reducing emissions, and if this creates a competitive disadvantage for some European enterprises, these will be able to enjoy special free-of-charge quota assignments.

To the political uncertainties over distribution of free emission quotas is therefore added the possibility that further free quotas are assigned to the most energy-hungry enterprises according to the choices of other sovereign nations. This generates a number of questions: From whom will these further free quotas be subtracted? Or are they to delay the reduction objectives? Which energy-hungry enterprises will receive themand in which industries?

The definition of “certainty,” so much in vogue in Brussels, apparently includes as a variable the political choices of an undefined number of foreign countries over the next 12 years.

The lesser evil

If one must choose between two unnecessary evils, it is wiser to pick the lesser one. Thinking about the costs of climate strategies means thinking about their benefits as well, and therefore the opportunity of imposing binding domestic targets.

This is particularly important in light of the substantial scientific uncertainties that remain concerning the global warming phenomenon and on the high probability that the benefit question will remain politically isolated in the short term in the effort to reduce emissions.

From this stems the substantial practical uselessness of the European policies, even if they were justified, effective, and efficient, because Europe represents an important but nevertheless minor and relatively decreasing fraction of global emissions.

Strictly connected to these questions is the issue of the political feasibility of climate policies. There is virtual unanimity among experts that from the political point of view, a cap and trade system is easier to launch than a carbon taxthe direct alternative to cap and tradeas the tax regulates prices instead of emission quantities. The European story provides evidence of that. However, the price of having a cap and trade systemthe option with less political resistanceis having a system that is volatile, opaque, and arbitrary.

A carbon tax, on the other hand, at least can provide a more predictable environment to businesses while creating fewer occasions for rent-seeking or corruption, because the degree of political arbitrariness is lower with a carbon tax. From a certain point of view, therefore, the option with less political desirability due to the difficulty of garnering consensus on a tax and the need to substantially reformulate the fiscal system actually has an advantage over cap and trade. This is because the politically less-feasible option guarantees that the measure will be taken only when a truly large portion of the population is willing to pay more to obtain a certain environmental goal.

For the same reason, it will be easier to abrogate the taxa move politically less difficult than cancelling regulations as encrusted with lobby activities as they are obscure to most peoplewhen and if it becomes evident that the European strategy is not sustainable or that global warming is a problem less severe than what is believed today.

Before following the European example, the next US president might want to further examine this state of affairs, visit Europe, and personally see that a failing policy in Europe can hardly lead to a healthy one in America.

References

- Methane (CH4), nitrous oxide (N2O), sulfur exafluoride (SF6), petrofluorocarbons (PFCs), and hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs).

- Industries covered by ETS represent only about 50% of European emissions. Other industries, such as agriculture, transportation, and construction are subject to other specific regulation aimed at reducing emissions.

- European Commission, “Proposal for a Directive of the European Parliament and of the Council amending Directive 2003/87/EC so as to improve and extend the greenhouse gas emission allowance trading system of the Community,” COM(2008)16, Jan. 23, 2008, (http://ec.europa.eu/environment/climat/emission/pdf/com_2008_16_en.pdf), p.2. On this specific point there is no consensus: see John Norregaard and Valerie Reppelin-Hill, “Taxes and Tradable Permits as Instruments for Controlling Pollution: Theory and Practice,” IMF Working Paper, No.13, 2000, (http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/wp/2000/wp0013.pdf).

- European Commission, COM(2008)16, p.2.

- Ibid, p.4.

- Ibid, p.7.

- Joscow, Paul L., Schmalensee, Richard, “The Political Economy of Market-Based Environmental Policy: The US Acid Rain Program,” Journal of Law and Economics, Vol. 41, No.1, 1998, pp. 89-135.

- European Commission, COM(2008)16, p. 8.

The author

Carlo Stagnaro ([email protected]) is energy and environment director at Istituto Bruno Leoni, a free market think tank based in Milan. He also serves on the editorial board of the Italian journal Energia. Stagnaro received a degree in environmental engineering from the University of Genoa and has written extensively on environment and energy issues, including global warming, energy and climate policies, liberalizations, and privatizations in the enerwgy sector. He is also a regular contributor to the Italian daily magazine Il Foglio.