COMMENT: Iranian oil industry, 100, showing wear

The Iranian oil and gas industry approaches its 100th anniversary bloated, corrupt, and nearly bankrupt, managing four times the employees but two-thirds the oil production it had before the Islamic Revolution of 1978-79.

The industry began life on May 26, 1908, when William K. D’Arcy discovered commercial amounts of oil in southwestern Iran, giving rise to Anglo-Persian Oil Co., later called Anglo-Iranian Oil Co. Its history, characterized by stormy relations between the Iranian government and international oil companies, includes nationalization, participation in the formation of the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries, growth coupled with technological advance, and eventual decline.

It’s a history that demonstrates the benefits a healthy oil and gas industry can bring to a country rich with hydrocarbon resources. It’s also a history that shows the regrettable results of mismanagement by a revolutionary regime concerned more about political control than about economic performance.

Route to nationalization

Nationalization of the Iranian oil industry followed years of unsuccessful negotiations between the government and Anglo-Iranian Oil.

Throughout the global economic depression of the decade before World War II, the government sought a greater share of revenue from oil produced in Iran, eventually settling for an increase of only 2 British shillings/tonne of exported oil. Its efforts to secure a fair share of oil revenue during and after the war failed.

From the Iranian viewpoint, Anglo-Iranian Oil sought only to prolong the colonization of Iranian oil rather than to commercialize it, making nationalization inevitable. The government acted on Mar. 20, 1951, with the formation of National Iranian Oil Co. (NIOC).

For more than 3 years after nationalization, the entire Iranian petroleum industry was shut down, and Abadan refinery, the largest in the world at that time, remained idle. The crisis ended with a change of administration in Iran and a new agreement with not only Anglo-Iranian Oil’s successor, British Petroleum Co., but also the largest international oil companiesthe so-called seven sisters.

The companies formed the Iranian Oil Consortium in October 1954 to work in partnership with NIOC. Their shares were BP 40%; Royal Dutch Shell 14%; Standard Oil Co. of California, Standard Oil Co. of New Jersey, Texas Oil Co., Gulf Oil Co., and Mobil Oil Co. 8% each; and French Oil Co. 6%. Once again Iranian oil started to flow.

The Iranian share of profits in the consortium agreement was not impressive by modern standards, barely matching Aramco’s 50-50 profit-sharing agreement in Saudi Arabia. However, Iran’s success in nationalization of its oil industry became a model for other oil-producing countries, particularly the Arab producers in the Persian Gulf region, which nationalized their oil industries in the following years.

Era of development

From 1954 onward was an era of construction and economic development in Iran. The successful application of nationalization and the recapture of oil wealth inspired Iranians and stimulated economic expansion for a quarter of a century.

In 1957, the government of Iran established a new standard for oil agreements worldwide: the principle of 50-50 profit sharing plus 25% income tax payable by international oil companies. Thus was the concept of 75-25 profit sharing created.

Agip and Pan American Oil Co. were the first companies to participate with NIOC on the basis of the 75-25 contracts. This kind of agreement, although not popular with international oil companies, caught on quickly in oil-producing nations.

In the following years, NIOC captured parts of the East European markets, to the dissatisfaction of major oil companies. Iran also quickly recognized the value of the gas that had been flared under the consortium contract. Under an unprecedented agreement with the former Soviet Union, Iran began to export moderate volumes of gas in exchange for its first large steel mill.

In 1973, after long and difficult negotiations, the government dissolved the consortium, 6 years before the termination date of the original agreement. With that act the Iranian oil industry became nationalized not only officially but in practice as well. NIOC became the essence of the oil industry in Iran and took on the responsibilities and challenges that went with a modern and well-established oil company.

The company had grown from a passive office in 1951 after nationalization to an active, mature, and well-respected international oil company in 1973. Its managerial team by then was well-trained and experienced.

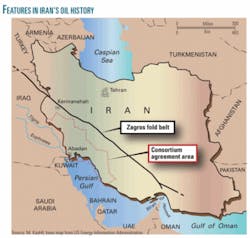

After 1973, Iranian oil production easily surpassed 6 million b/d, and NIOC kept an average of 52 drilling rigs active in the Zagros fold belt (see map). New pipelines were laid to refineries and exporting terminals. Nine well-maintained refineries were in operation, and two more were near completion, with total capacity reaching more than 1.58 million b/d. The largest and the most modern terminal (Azarpod) in the region was constructed in the Persian Gulf to accommodate very large crude carriers.

Also in the early 1970s, NIOC expanded internationally, investing heavily in refinery construction in South Korea, India, Senegal, and South Africa under agreements to provide crude oil to the new facilities. NIOC also signed a preliminary agreement to enter US markets to refine crude and distribute products.

All of this was accomplished while Iran played a leading role in decision-making by OPEC, which it helped found in September 1960.

Revolution, destruction

The Islamic Revolution changed everything. A healthy, economically sound oil industry gradually ceased to exist. Production of over 6 million b/d dived to below 3 million b/d after the revolution and never reattained its prerevolution peak. Experienced and well-trained oil workers from all levels in every industry sector were arrested or terminated; many fled the country to escape execution.

Before these chaotic acts of retaliation showed any sign of abatement, the 8-year war with Iraq began with an Iraqi invasion in September 1980. A result of this nonsensical conflict was the destruction of the Abadan refinery, the Kermanshah refinery near the Iraqi border, many miles of pipelines and oil field installations, particularly in southwestern Iran, and major production platforms in the Persian Gulf.

Twenty years after the war ended, the damage to the oil industry is still evident. Hardly any of the affected installations have been replaced or repaired by the Islamic regime.

Currently, oil production is barely 3.8 million b/d, declining at an average rate of at least 200,000 b/d/year (OGJ, Feb. 10, 2003, p. 20). Lack of regular maintenance and rare replacement of worn-out parts and equipment for the past 29 years have caused much irreversible damage to the Iranian oil industry. Uncontrolled production during the war with Iraq and in the aftermath, lack of investment and introduction of new and modern technologies to the Iranian oil industry, andmost of allever-increasing sanctions by the western powers and by the United Nations Security Council coupled with poor management with roots in bribery and corruption, have driven the Iranian oil industry to the brink of bankruptcy (OGJ, Jan. 28, 2008, p. 20).

The throughput capacity of the refineries in Iran has been so limited that the Islamic Republic has been forced to import petroleum products, including gasoline, from foreign producers in order to meet public needs. To make the situation worse, presently there is only one gas station in Iran for every 37,000 automobiles, far below the ratios of other oil-exporting countries.

NIOC changes

NIOC before the revolution was a very effective organization with a well-functioning management. It operated efficiently not only in refining but also in production, petrochemicals, natural gas, domestic performance, and international marketing.

It accomplished all this with merely 32,000 employees. Presently, with the creation of the Ministry of Petroleum in addition to NIOC, a near-bankrupt oil industry is struggling to survive with nearly 112,000 employees.

In the name of privatization, the Islamic Republic divided NIOC into pieces, each given to an individual affiliated or ideologically associated with the regime. In most cases, each sector registered under a new company outside of Iran.

Many formally named and unnamed oil companies and petroleum-oriented businesses have been established under the regime for the sole purpose of collecting bribes under the guise of commissions in order to prepare and fix contracts with the Ministry of Petroleum. Under these conditions one has to be connected to the system to be successful. The connection too often requires illicit payments.

In a well-publicized example, Statoil of Norway in 2006 acknowledged the payment of bribes in 2002 and 2003 to an Iranian official to secure a development contract for part of offshore South Pars gas field. The company paid fines and disgorgements in the US and Norway totaling $21 million and submitted to a 3-year deferred-prosecution agreement.

Last year, top executives of Total came under formal investigation by French authorities for suspected bribes paid in 1997 in connection with contracts for two South Pars development phases. Total in March 2007 acknowledged the investigation and said the agreements under investigation complied with “applicable law.” France didn’t totally prohibit the payment of bribes until 2000.

The oil ministry of the Islamic Republic has a section under the name of “office” for foreign negotiations and contracts. NIOC, now part of the ministry, has a similar department that independently negotiates and signs contracts with foreign oil companies. Therefore, one organization has different offices for the same purpose.

Often a contract is awarded to an unqualified domestic “oil company” to carry out a specific assignment. The “oil company” then delegates the assignment to an inexperienced foreign company of East Asian origins, awarding a much cheaperpossibly half the originalamount while appropriating the remainder for itself. This results in a great setback for the Iranian oil industry. All of these corrupt actions are knowingly carried out to benefit only a small group within the system.

Iran’s corruption is widely acknowledged. In the 2007 Corruption Perceptions Index published by Transparency International, the country scored 2.5 on a scale in which 10 means “highly clean” and 0 means “highly corrupt.” Other countries receiving that score were Burundi, Honduras, Libya, Nepal, Philippines, and Yemen.

The Iranian regime’s deceptions extend to oil and gas reserves disclosures. While most oil-producing countries publish estimates of their proved reserves periodically, state-controlled firms in Iran, such as NIOC, do not let outsiders verify their extremely inflated estimates (OGJ, Nov. 1, 2004, p. 20). Oil industry authorities in the Islamic Republic, in order to secure loans from international monetary organizations, to attract private investors and major companies, and inflate Iran’s production quota in OPEC, have always provided false reserves information. Further, reserves estimates are used as political tools, bolstering power and prestige for the Islamic Republic.

There is a massive managerial vacuum in Iran due to a bureaucratic and hierarchical decision-making structure and the fact that many decision-makers are not necessarily appointed for their managerial competence. Because only a few leaders in the Islamic Republic control the wealth, the system is incompetent and open to abuse.

Shrinking income

Oil accounts for about 90% of Iran’s hard-currency income. Increased oil prices in the last several years have encouraged many members of OPEC to invest this extra cash flow in their own petroleum infrastructures.

Iran and Venezuela are exceptions. For the past 29 years, Iran has produced an average of 3.395 million b/d of oil and exported an average of 2.445 million b/d. The average export per year has been 892.425 million bbl. The Islamic Republic thus has sold 25,880,325,000 bbl of crude oil in the past 29 years at an average price of $30.96/bbl, earning more than $801.2 billion.

Where has this huge amount of money gone? Certainly, none of it was invested in Iranian oil infrastructure, which badly needs renovation and repair, upstream and downstream.

The Islamic regime of Iran is one of a few governments that the world community has accused of promoting international terrorism, purchasing and storing weapons of mass destruction, and abusing human rights. Critics, including western democracies, believe oil revenues are making these programs possible.

No one can recall any part of the world where a country so rich in manpower and natural resources (about 10% of total world oil and about 17% of total world gas reserves, according to official estimates) and with such a huge well-educated middle class, has experienced such a profound and rapid deterioration of its living standards as Iran has since the revolution of 1979.

The author

Mansour S. Kashfi ([email protected]) is president of Kashex International Consulting. He also is a faculty member at Eastfield College in Dallas. Kashfi has over 40 years of research experience in a wide range of oil and gas, geology, policy, and economic issues, with expertise in the petroleum geology of the Middle East and world oil market development. He has published more than 50 books and articles. Kashfi holds a BS degree in geology from University of Tehran, an MS in geology-subsurface stratigraphy from Michigan State University, and a PhD in geology-tectonics and sedimentology from University of Tennessee.