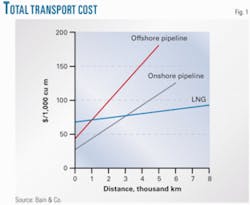

The relatively short distance between North African natural gas fields and Europe’s consumer markets makes North Africa the most attractive source to meet future European gas demand. Most European ports and pipeline access points lay well within 2,000 km of North African production, and transportation will add less than $100/1,000 cu m via offshore pipelines and little more than $50/1,000 cu m for gas that moves via onshore pipes or if shipped in a liquefied state (Fig. 1).

This article assesses the relative advantages and disadvantages of sourcing gas for European consumption from North Africa and the Caspian region.

Background

European efforts to secure dependable new natural gas supply sources come at a time of upheaval in Europe’s gas industry. To stimulate competition, EU regulators have increased efforts to weaken national oligopolies. Major non-EU gas producers like Gazprom and Sonatrach, meanwhile, are trying to enter Europe’s attractive downstream markets, including those in the UK, Germany, and Italy.

Facing new obstacles in their domestic markets, European energy companies, utilities, and their financial backers concurrently face increasing difficulties in winning access to promising gas fields beyond EU borders. They are contending with huge business risks as they decide whether to stake out their own positions or grow through mergers and acquisitions to build the exploration, production, and transportation infrastructure required to move gas from wellhead to end-user.

EU governments, producers, and consumers face two major hurdles. Gas prices have risen sharply. The EU’s increased reliance on gas to replace less environmentally friendly coal in power generation, along with a surge in new energy demand from China and India, have nearly doubled natural gas prices during the past 2 years.

Capital costs are also rising. Investments in new pipeline and LNG facilities already in the works are slated to increase Europe’s gross transport capacity by 27% by 2013. The global gas industry is consolidating rapidly. Mergers and acquisitions in the sector have increased at 40%/year compounded over the past 3 years, to more than $370 billion in 20072.

EU gas consumers also face ongoing political uncertainty and heightened security risks. Russia has shown that it is prepared to flex its energy muscles as a political weapon against its former Soviet and Warsaw Pact neighbors, using the threat to shut off supplies to force them to renegotiate long-term contracts. Political instability across the gas-rich nations of Central Asia, the Middle East, and North Africa poses an ongoing threat to the security of EU energy markets.

Faced with these uncertainties, Europe’s energy companies are looking to diversify supply sources. Twenty-one major pipelines and LNG regasification facilities are currently either under construction or planned for completion by 2013, with 250 billion cu m/year capacity to transport new supply from Central Asia and North and West Africa; enough gas to meet about half of EU’s annual consumption (Tables 1-2).

Caspian

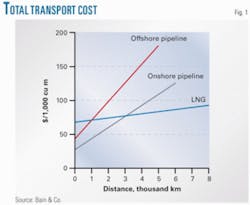

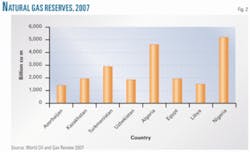

Many of the most promising new gas fields in terms of proven reserves lie in the former Soviet republics of Central Asia, mainly in Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan. The four nations’ combined reserves total slightly more than 8 trillion cu m, with Turkmenistan accounting for roughly 40% of the total. With 2007 annual production of 61.6 and 58.7 billion cu m, respectively, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan also rank as the region’s leading producers (Fig. 2).

Gas sourced from Central Asia, however, faces large political and regulatory risks. Of the five proposed pipeline projects that will carry gas from the region, three will be controlled either directly or indirectly by Russia, including the Blue Stream pipeline’s extension. A joint venture between Gazprom and Eni, Blue Stream will by 2010 transport 16 billion cu m/year 1,250 km from the Russian pipeline network through Turkey to Hungary.

Two other proposed pipelines running through Turkey aim to connect the Caspian fields directly to EU markets. The 3,300-km Nabucco pipeline will feed 31 billion cu m/year of gas into Europe, connecting the Caspian region via Turkey to a terminus in Austria. Nabucco’s schedule calls for completion in 2012, but doubt remains whether it will be built at all.

Gazprom and Eni’s recently agreed 560-mile, 30 billion cu m/year South Stream pipeline, running across Bulgaria to deliver gas from Azerbaijan and Iran to Hungary and Italy, may preempt the need for Nabucco. South Stream’s proposed route runs from Russia to Bulgaria across the Black Sea, bypassing Turkey. It then forks in two directions: one going north to Austria and northern Italy; the other south to Greece and southern Italy. The companies expect South Stream to be completed by 2013.

Another project that would create a direct South Mediterranean gas ring to Central Asia and due to begin construction this year is the Italy-Greece Interconnector pipeline, a joint venture of Edison Italia and DEPA. Designed to deliver 8 billion cu m/year of gas and to come online by 2012, IGI has broad EU support but is still in the permitting process. Whether it ends up meeting its goals depends on completion of three other pipelines connecting it to the Turkish network and ultimately to Iran and Central Asia.

Africa

Sourcing gas from the vast, and still largely untapped, North and West African fields of Algeria, Egypt, Libya, and Nigeria offers energy and utility companies more promising commercial prospects. Combined, the four nations’ proven reserves topped 13 trillion cu m in 2007, nearly double those of the Caspian region, and production was also greater (Fig. 3).

African gas also lies much closer to European markets than Central Asia’s and is better situated to permit direct import via either pipeline or LNG delivery. Two new pipelinesthe 210-km Medgaz connecting Algeria to the southern coast of Spain and the 900-km Galsi running undersea from Algeria to Sardiniaare scheduled to come on line in 2009 and 2012, respectively. Each will feed 8 billion cu m/year of gas into Europe’s pipeline grid.

Completion of a third pipeline, the Arab Natural Gas Pipeline, linking North African-sourced gas with supplies coming from Central Asia, faces greater problems. The multiphase plan foresees construction of a line transporting 10 billion cu m/year of gas across deserts and undersea from Egypt; traversing Syria, Lebanon, and Jordon en route to Turkey, where it would connect with Nabucco. Beyond any questions regarding Nabucco, the complicated politics of the Middle East keep the Arab Natural Gas Pipeline’s overall fate uncertain, even while sporadic construction progress is reported.

A dozen new LNG regasification terminals slated to open from western France to Trieste, however, will add another 100 billion cu m/year of new import capacity by 2012.

African infrastructure

Africa’s underdeveloped and fragmented infrastructure poses the biggest impediment to moving its natural gas resources into Europe, while at the same time offering Europe’s large and mid-sized energy companies and investors an opportunity.

Conditions for improving Africa’s infrastructure are more favorable than they have been for some time. Among gas-rich North African countries, Egypt’s production and export capacity has grown most rapidly, making it the most attractive market for new entrants. Completion of three LNG trains with two more in the works has helped Egypt boost production by 14%/year for the past 5 years.

Lifting US sanctions on Libya in 2004 has brought US oil and gas companies back into the country where they are now competing with European companies for exploration and production concessions under a new open-bid process. Algeria, already North Africa’s largest natural gas producer with an output of 101 billion cu m/year recently began a long-delayed new round of bids for oil and gas leases.

Newcomers to the region face three options: pursue upstream exploration and production leases, invest in downstream export infrastructure by building gas liquefaction terminals, or both. Securing production facilities has emerged as the preferred entry strategy. Companies that invest in exploration and production and can tap their own gas supply for export face less risk regarding the terms and volumes at which supplies will be available.

Once a company commits to establishing an upstream presence, it must decide whether to enter the market by building a position from scratch or acquiring a company already active in the region. Companies that choose to pursue an organic-growth strategy by bidding for new lease concessions must further decide whether to do so alone or in partnership with other companies.

A company that wins an exploration and production concession must be prepared to build an on-site organization in cooperation with local partners and government agencies. It must also navigate the sometimes intricate rules governing joint ventures with state-owned partners.

Egypt has one of the more straightforward and consistent regulatory frameworks for exploration and development agreements, but the details remain important. A foreign firm entering a 50-50 joint venture with EGAS, the state-owned gas company, bears all initial exploration risks and development costs. Once a field starts producing, the contractor may recover its initial investment outlays and all operation costs up to 40% of production. Any further production is then split equally between the contractor and EGAS.

Companies might choose to join forces to lease concession rights with other foreign partners already active in North Africa, but will obviously still need to perform thorough due diligence regarding the quality of the lease. They must also establish clearly from the outset how responsibilities will be shared and then be prepared to manage the relationship. Entering a North African market through partnerships, however, can still serve as an effective means of building local expertise and establishing a successful long-term presence.

The quality of a target company’s lease concessions ranks among the most important considerations for companies wishing to enter North Africa through acquisition. Beyond such standard key indicators as the total volume of gas reserves, the ratio of production to reserves, and production costs, important issues specific to North Africa’s underdeveloped infrastructure require consideration. Chief among these is the distance from producing fields to transportation and export facilities. Companies that control existing pipelines or LNG ports, or holding a stake in projected ones, would be especially attractive acquisition targets.

The bottleneck in regional export facilities remains particularly acute in Egypt and Libya.

References

- BP Statistical Review of World Energy, 2007.

- PriceWaterhouse Coopers Power Deals, 2007.

The authors

Julian Critchlow is a partner with Bain & Co., based in London. He has also served as a chemical engineer at ICI and Exxon. He holds MA and masters of engineering degrees from Cambridge University (1986,1987) and an MBA with honors from The Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania (1991). He leads Bain’s European energy and utilities practice.

Roberto Prioreschi is a partner with Bain & Co., based in Rome. He has previously worked for Procter & Gamble and Enel SpA. He is an honors graduate in economics from Spienza University, Rome (1992). He is a member of Bain’s energy and utilities practice.

Joseph Scalise is a partner with Bain & Co., based in San Francisco. He has previously worked at the board of governors of the US Federal Reserve System in Washington, DC. He holds a BA degree summa cum laude from Lehigh University (1993) and an MBA from The Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania (1998). He is a member of Bain’s global energy and utilities practice.