SPECIAL REPORT: Iran’s gasoline woes persist despite rationing, price hikes

Iran’s gasoline shortage and its growing dependency on imports have been the subject of discussion and debate, both in and outside Iran. The problem, which began after the 1980-88 Iran-Iraq war, has worsened. Its resolution has become more difficult because successive postwar administrations have failed to address the issue boldly and decisively.

Today, the gasoline shortage and the estimated $40 billion/year subsidy that the government pays for this and other fuels is a huge economic burden to the state. Because of Iran’s controversial stance on certain international political issues, it also has become an important national security concern.

Recognizing the gravity of the situation, President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad recently launched an initiative that raised the price of gasoline and, for the first time, introduced an elaborate rationing system.

This article will describe the background of the problem, the deterioration in Iran’s gasoline prices relative to international prices of gasoline and crude oil, the huge losses borne by the National Iranian Oil Co. (NIOC) in its downstream operations, and the persistent public expectations for the government to provide cheap fuel despite these heavy losses.

The article also evaluates the recently adopted rationing scheme, its efficacy and chances of success as a long-term policy measure to resolve current problems and pave the way for the eventual privatization of NIOC’s downstream operations.

In addition to decreasing demand, Iran also is intensifying efforts to boost its own output of gasoline and other fuels through a major refinery expansion and modification program.

Iran’s gasoline problem

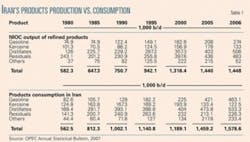

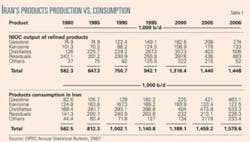

Iran’s refining capacity has not kept pace with rapidly growing demand, and this imbalance has necessitated a rapid surge in gasoline imports (Table 1). This has created a huge financial burden on the state and jeopardizes the national security of the country by making it vulnerable to import disruptions. Ahmadinejad’s initiative aims to address these concerns.

Ahmadinejad has acted much more boldly than his predecessors. His rationing plan has provided a demand-management apparatus and has put into place a scheme that might be fine-tuned if needed and used more vigorously to mitigate adverse impacts of a major interruption in gasoline imports. However, it falls short of being a long-term solution to a perennial problem that has dogged every administration since the 1980-88 Iran-Iraq war.

The key factors contributing to Iran’s gasoline problem are the government’s ownership of downstream assets and its intervention in a process that should function through free market mechanisms rather than by state controls and government fiat.

Iran is not unique in this respect. In almost all OPEC countries, government ownership of energy-related assets and intervention in markets are prevalent, and for the same reason most of them face similar issues. However, owing to its large industrial base, rapid growth, large population, unique demographic profile, and controversial stance on international political issues, Iran’s case is much more complicated.

Iran’s population has more than doubled to about 70 million today from about 34 million in 1979, nearly half 30 years old or younger. The vehicle fleetnow as many as 7 millionand industrial activities have grown rapidly. Improvements in fuel efficiency in almost all sectors, particularly transportation, have been lackluster.

Meanwhile, the prices of gasoline and other fuels have been kept artificially low, resulting in astronomical growth in consumption of these products and even their smuggling to neighboring countries.

Rebuilding capacity

In addition to slowing gasoline consumption, Iran is attempting to lessen its reliance on imported gasoline by increasing its own production.

Its ability to produce crude oil and petroleum products was severely undermined by the 1980-88 war and by a series of trade constraints and economic sanctions imposed on the country since the 1979 revolution. The war with Iraq heavily damaged oil fields and refineries, resulting in considerable declines in the country’s ability to produce and refine crude oil.

The post-1979 trade restrictions and economic sanctions imposed by the US and others made it much more challenging to restore or expand refining and oil production capacity. Whereas the decline in oil production led to lower exports and revenues, the damage to refineries forced the country to meet its rising fuel consumption with costly imports.

Despite numerous constraints and economic sanctions, however, the country has managed to restore oil production to about 4 million b/d, and refining capacity is rising, although production output remains insufficient (Table 2).

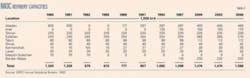

In a major 3-4-year refinery expansion program, National Iranian Oil Engineering & Construction Co. (NIOEC) plans to increase capacity to more than 3 million b/sd from about 1.7 million with the construction of seven grassroots refineries and the upgrading or modification of five existing refineries to produce more gasoline (Table 3). NIOEC reported that gasoline production capability will rise to 140 million l./day, up from 40 million l./day, to become 35% of the total products output, compared with the current 16% of the total.

Tempering consumption

Until these facilities are on stream, however, a successful means must be found to temper consumption. Past responses to the imbalance in gasoline supply and demand were lethargic, inadequate, and ill-conceived.

In a market-based economy, a circumstance of this nature would have led to rapid increases in petroleum product prices, thereby discouraging consumption and generating cash for investments in refineries. But in Iran, the nominal prices of productsparticularly gasolineeither remained unchanged or rose slowly and with considerable lag.

Even in a state-run enterprise such as a national oil company, one would expect a government to raise petroleum product prices, at least in tandem with inflation or with the increase in the opportunity cost of crude oil, i.e., what it could fetch if exported. But for numerous reasons, some clearly political, no post-Iraq-war administration until recently has taken the initiative to address this problem boldly. Consequently, rather than generating revenue and income for NIOC and the government, all refineries in the country have operated perennially with huge losses and consumed a considerable portion of the funds generated from oil exports.

Frustrated by this state of affairs a few years ago, former Oil Minister Gholamreza Aghazadeh was quoted in the press as lamenting that he would be happy to deliver gasoline free to any entity at the refinery gates if it accepted the sales and distribution responsibilities.

Some believe the country’s hesitation to raise gasoline prices goes back to an event in the early 1960s. There was an attempt in 1964 to raise the price of gasoline to 10 rials/l. from 5 rials/l.a 100% increase. According to those in decision-making positions at the time, the purpose of this price hike was to generate additional revenue rather than to discourage consumption. The initiative was short-lived. Due to public opposition and the assassination of the prime minister at the time, the price of gasoline was lowered to 6 rials. Although there is no convincing evidence that the assassination was in any way related to the gasoline price increase, some believe it has contributed to the succeeding governments’ hesitation to raise gasoline prices adequately.

‘Cheap’ gasoline?

Although a large percentage of the driving population in Iran is of the post-revolutionary period, the “cheap” gasoline era of the 1960s and 1970s still evokes nostalgia in the minds of many.

The “cheap” gasoline price of that era is often mentioned in discussions criticizing the government’s energy policy. However, gasoline at 6 rials/l. or at 10 rials/l. for a subsequently introduced higher octane grade called “Super”about 23 rials/gal in the 1960swas not really cheap, being either close to or surpassing international prices. At the then-prevailing 70 rials-to-$1 exchange rate, 23 rials/gal translated to $0.33/gal.

The average retail gasoline price in the US at the time was about $0.25-0.30/galsubstantially lower than in Iran.

Today, gasoline prices in the US are the lowest among all industrial countries, including Canada, which is a major oil exporter, and yet the current 1,000 rials/l. in Iran is only a small fraction of the current US prices.

In the 1960s, crude was around $1.60/bbl. At about $0.33/gal or $13.86/bbl, the retail gasoline price in Iran in the 1960s was about nine times the price of crude oil.

At today’s exchange rate of about 9,300 rials to $1 and the crude oil price at $85/bbl, a retail gasoline price at even 4,900 rials/l. (five times the 1,000 rial price that has been in effect since April 2007) would cover only the opportunity cost of the crude, still leaving NIOC to absorb refining, distribution, and sales costs. Iran’s domestic gasoline prices could easily top 10,000 rials/l. if parity with international prices were the real objective.

Failed economics

Although there are no consistent and reliable figures for the amount of subsidy provided to consumers of gasoline and other fuels in Iran, it is obvious that it is huge by any standard. Iran now consumes some 1.5-1.7 million b/d of petroleum products. Thus the annual subsidy, even at the artificially inflated exchange rate, could easily top $40 billion.

The weight of these subsidies is not only on the shoulders of the government but also on NIOC’s downstream operations. Iran has had the luxury of continuing to operate these money-losing refineries only because of huge cash flows generated from crude oil exports.

The multifold increase in crude oil prices over the last few years has provided the government with the financial wherewithal not only to continue operating these refineries at great losses but also to add to capacity and upgrade some of them.

Obviously, this subsidy trend is not sustainable. Most observers believe the government will be forced to follow a free market model in pricing its gasoline and other petroleum products and gradually phase out its subsidy program. Procrastinationas has happened in the pastwould only make the task of tackling this problem progressively more difficult.

Ahmadinejad’s program

Over the last year or so, Iran’s high degree of dependency on imported gasoline has been the subject of numerous analyses in the West and has been identified as Iran’s Achilles’ heel. Accordingly, it has been asserted that the economic damage and hardship resulting from a successful attempt by the West to halt gasoline exports to Iran could cause enough unrest to undermine Ahmadinejad’s presidency.

In reaction to these potential threats and the damaging impact of the highly subsidized gasoline prices on the overall economy and on NIOC, Ahmadinejad last May launched a plan that included both a price increase and a rationing program. The gasoline price was raised by 25% to 1,000 rials/l.a tepid amount compared with what was needed to effectively address the problem.

The plan also includes a rationing scheme through the use of a ration card called “Houshmand” or “smart card.”

The scheme consists of different ration allowances for varied types of vehicles and usesranging from 100 l./month for private cars to 800 l./month for taxis.

By adding the rationing system to the price increase, the government in effect seemed to concede that it doesn’t have confidence in the demand-reduction impact of the price increase alone, and its hope of reducing demand rests largely on the rationing scheme.

The initiative triggered unrest on a small scale initially and resulted in some gas stations being set on fire, but it seems now to be firmly in place and fully implemented.

The goal of the combined price increase and rationing is to reduce gasoline consumption to about 39 million l./day from 75 million l./daya 47% reduction. According to some sources, gasoline demand has declined nearly 20%, resulting in a decline in imports of 50% and an almost complete halt to smuggling to neighboring countries.

There is a degree of skepticism among analysts and other observers as to the plan’s long-term prospects for success, however. Most believe the issues surrounding fuels such as gasoline, heating oil, and natural gas, which enjoy huge subsidies, are not resolved. Rather than opting for large, systematic price increases that would reduce consumption and bring the domestic price of gasoline closer to international levels and that would prepare the country for the eventual privatization of downstream operations, the government opted primarily for a rationing method that has been tried many times in other parts of the world and has almost always failed to achieve a long-lasting, tangible result.

Ahmadinejad, however, reportedly favors a combination of a relatively small price increasesmall compared to what is neededand adoption of a strict rationing scheme for two reasons. First, he believes that too large an increase in price would be not only inflationary but also unfair to the low-income and middle classes. Second, he considers rationing a “catch-all” device that distributes the pain and hardship equally and fairly to all consumers.

Many experts, however, argue that rationing is a form of “command and control,” which requires a huge bureaucracy. Rationing, they say, almost always fails to achieve its goals, including those of fairness and benign inflation. Even if it initially succeeds on a limited basis, success will be short-lived. Moreover, rationing, by its nature, carries a huge stigma because its adoption signifies the failure of or lack of trust in market-based measures. Free markets provide competitive prices, which in turn signal to the decision-makers how to utilize their resources in the most efficient and optimal manner. Interventions and rationings, on the other hand, result in distortion of these signals and thus in wasteful decisions.

Critics also expect the rationing plan to fail because it is prone to manipulation, cheating, and the emergence of black markets, despite its high administrative cost. In fact anecdotal evidence suggests that black markets have already emerged, and cheating and abuses of the system are abundant. Whether the government will be able to prevent these abuses by adding new features to its smart cards is not yet clear. But it is obvious that if the rationing system is not followed up by rapid price increases and a gradual phasing out of the subsidy system, abuses are certain to continue or even worsen.

Ironically the flaw in the rationing system that allows smart-card holders to cheat and sell part of their ration in the black markets has inadvertently produced a positive result and indirectly helped to enhance the scheme’s effectiveness. Paradoxically, this occurs because the cheating by smart-card holders introduces some elements of the free market incentives to the rationing scheme.

Even though the 25% increase in price may not generate enough incentives for conservation, the opportunity to sell part of the ration at much higher prices (reportedly at 6,000-11,000 rials/l.) on the black markets not only raises the overall average price of gasoline but also gives the card holder incentive to conserve and sell the unused portion of his ration in the black market. Forgoing the opportunity to make that additional income is tantamount to paying that high black market price for the quantity not offered. The same incentive also discourages the smuggling of gasoline to neighboring countries because domestic black markets offer a better opportunity for profit.

Pragmatic approach

Despite repeated calls for action from different circles within the country, no one seems to suggest that either a huge price increasei.e., to raise fuel prices to international levels in a very short periodor complete privatization of downstream operations is feasible at this time. Such initiatives are considered radical, impractical, and extreme. Yet suggestions abound for galvanizing the rationing scheme or making it more effective. Some have suggested replacing the single price in the rationing scheme with a new progressive pricing mechanism where the price would rise with the level of each vehicle owner’s consumption.

Others have suggested a combination of rationing and a semifree-market approach. In this approach, reportedly discussed in Majlis (the parliament), the present rationing system would continue, but consumers would also have the choice of purchasing unlimited quantities of gasoline at the quasi free-market price.

Initially one or two pumps in each gas station would be set aside to sell gasoline at a much higher price with no limitations on the quantity. The price in these pumps that target affluent consumers would rise much faster until it approached parity (or near parity) with international prices. Meanwhile, the price in other pumps would also rise, but at a much slower pace to allow other consumers to adjust more gradually to the higher prices. Within a few years, the prices for the rationed and nonrationed gasoline would converge. This would gradually prepare the public for much higher prices and pave the way for the eventual privatization of all downstream activities.

Inflation and fairness

Inflation, fairness, and affordability are issues frequently raised with regard to the need to increase fuel prices in Iran. Having been accustomed to unrealistically cheap fuel prices for so long, the public reacts negatively to any proposal to reduce or eliminate the subsidies. Rather than being assertive and educating the public on the dire consequences of continuing the status quo, past governments have succumbed to public opposition. Every administration in the past 2-3 decades has failed to face the issues head-on, instead adopting half-hearted measures. This has exacerbated the problem almost beyond remedy.

Most experts argue that the issues of inflation, fairness, and affordability merit close examination and analysis. However, their adverse impact seems to have been grossly exaggerated. Inflation is a monetary phenomenon, and with a proper monetary policy, the spillover from higher fuel prices can be small and manageable. Moreover, the resulting inflation cannot be long-lasting if it is not fueled by an unnecessary expansion in money supply. Interestingly, countries that keep fuel prices low through huge subsidies are almost invariably among those with very high inflation rates.

And the reverse often is true. For example, as a result of rising crude oil prices in recent years, gasoline prices in the US have more than doubled, and EU countries have seen their fuel prices rise sharply. Yet inflation has remained in check because of their measured monetary policies. On the other hand, inflation inVenezuelaone of the two countries with gasoline prices below those in Iranaveraged 39.3% during 1990-2004.

The argument for fairness and affordability also collapses under close examination. Fuels of all kinds are used much more by affluent citizens than by the poor or middle class. Therefore, rich people are the biggest beneficiaries of the fuel subsidies. In an efficient economy, the problems of fairness and affordability are not tackled by market interference; they are remedied by such measures as income subsidies or tax relief. Thus markets are allowed to function with minimum distortion and government interference.

Finally, national ownership of an industry’s production and operation is almost certain to result in unrealistic public expectations. For example, sharp increases in crude oil prices over the last few years have actually raised the amount of subsidies on gasoline and other fuels because of higher opportunity costs of the crude oil used in domestic refineries. Yet the public’s expectations for subsidies have become even more extensive. They seem to believe that when the government’s revenue goes up as a result of higher oil prices, so should the subsidies. Here again, one can clearly see the disadvantages of a government being involved in a business activity that should be owned and operated by the private sector.

Prospects for success

If history is a guide, one must be skeptical about the prospects of success for Ahmadinejad’s plan. His approach is bolder than others, which makes it appear to have a better chance. But if rationing fails in implementation, as many observers and experts expect, Ahmadinejad’s initiative will not significantly differ from those of previous administrations.

Those who believe rationing is a panacea would argue that the previous administrations failed because they resorted only to price increases. But in reality, their plans failed because their price increases were insufficient, as is the case with Ahmadinejad’s initiative.

Iran’s gasoline problem is deeply entrenched in all aspects of its economy and the life of its people. Left unchecked for decades, the problem of cheap gasoline and other fuels has become institutionalized. As a result, any initiative by the government to truly stem the problem will be extremely painful to the consumer, unsettling for the general economy, and risky for the government.

Some observes say Ahmadinejad would have a greater chance of success if he treated his rationing plan as a temporary measure, lowered his expectations for its success, completely precluded it from his long-term planning, and pursued his demand-reduction goals by resorting to price increases and improvements in fuel efficiency. These observers also believe his chances of success would improve considerably if he coupled his price increases with a well planned and executed financial assistance program to mitigate the financial hardship of higher fuel prices on low-income consumers.

Resolving the gasoline problem is a major challenge that has defied the will and wit of previous administrations. Only time will tell if Ahmadinejad is the man to succeed.

This article is a modified version of an editorial the author wrote for the Middle East Economic Survey, Vol. L, No. 50, Dec. 10, 2007.

The author

Cyrus Tahmassebi is an independent consultant who formerly was the chief economist and director of market research for Ashland Inc. During his 15-year tenure with Ashland, Tahmassebi gained international recognition for his oil market forecasts and views on energy-related issues. Before joining Ashland in 1981, he was a visiting fellow at Harvard University. Tahmassebi has long, broad-based experience in international oil and natural gas markets. He worked for National Iranian Oil Co. and National Iranian Gas Co. (NIGC) in senior management positions for over 16 years. During his years with NIGC, Tahmassebi was responsible for the economic-feasibility study of major LNG and pipeline gas export projects and participated in negotiations concerning these projects. He also represented Iran on OPEC’s gas committee. He received a BS and MS from Brigham Young University in Provo, Utah, and his PhD from Indiana University in Bloomington, Ind. He has written extensively on oil, gas, and energy markets and has given talks at various seminars and workshops worldwide.