Russia’s drive for power-2: Gazprom controls gas exports to Europe, Asia

Gazprom unveiled in September 2005 a short list of five foreign companies being considered as partners in Shtokmanovskoye, a supergiant gas-condensate field located in 350 m of water in the central part of the Barents Sea some 555 km east of Murmansk (see map, OGJ, Sept. 4, 2006, p. 70).

“Shtokman” clearly is a prize worth seeking. Its reserves are estimated at 3.7 trillion cu m of gas (131 tcf)-increased from 3.2 trillion cu m by the Russian Federation Nature Ministry’s State Commission for Mineral Reserves in January 2006-and 31 million tonnes of gas condensate. It is the fourth largest gas field in the world, slightly larger than Hassi R’Mel field in Algeria, and the third largest in Russia. The supergiant Persian Gulf North field-South Pars field straddling Qatar and Iran holds 1,400 tcf, and Urengoy and Yamburg fields in Russia hold 220 tcf and 140 tcf respectively.

The first stage of Shtokman field development as originally conceived was expected to involve output capacity of about 30 billion cu m/year, with as much as 24 billion cu m/year targeted as LNG. About 15 million tonnes/year of the LNG was scheduled for export to the US. Capital cost of the first phase of the project was estimated at $10 billion, including gas extraction, liquefaction, and a pipeline to shore, and LNG shipping.

Production start-up was scheduled for 2010-12, and many expect the total development costs to exceed the quoted figure of $20 billion, which equates to just $1.09/boe, based on its gas reserves.

The companies short-listed in 2005 excluded Exxon, Shell, and the Japanese companies Mitsui and Mitsubishi, which were fighting to maintain production-sharing terms in the Sakhalin project. Those named on the Shtokman short list were Statoil ASA and Norsk Hydro ASA-companies that have since agreed to merge-and Chevron Corp., ConocoPhillips, and Total SA. Expertise gained from developing the Snohvit LNG project under construction in the Norwegian sector of the Barents Sea is considered important, and Statoil and Total have a clear advantage in that regard. In addition, Hydro has participated with Gazprom in drilling the fourth Shtokman field appraisal well. Gazprom announced it would keep 51% of the project and would hold further talks to select a final lineup of two or three companies. Those talks lasted more than a year and involved each of the short-listed companies competing with each other to offer Gazprom equity shares in their international assets with strategic interest to Gazprom.

Revised Shtokman plan

In October 2006, however, Gazprom dismayed its foreign suitors by announcing that it was abandoning the bidding process and would develop Shtokman without any foreign equity partners under a plan that would export Shtokman gas by pipeline to Europe rather than export it to North America as LNG.1 At that time Gazprom justified its action by saying the potential partners hadn’t offered enough capital or attractive enough assets in return.

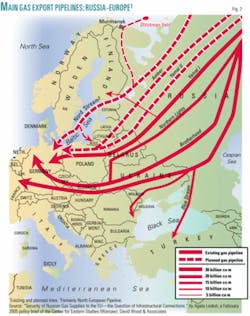

Under Gazprom’s revised plan, gas initially will be piped from the field to the Russian coast, across Russia to the Baltic Sea, and onward from Russia to Germany through the now-sanctioned joint Russian-German 1,200 km Nord Stream pipeline, formerly called the North European Gas Pipeline. Gazprom owns 51% of Nord Stream, and BASF AG and E.ON AG hold 24.5% each.

Original plans also called for an LNG liquefaction plant near St. Petersburg; whether this will now be built remains uncertain. Pipeline operations, however, are scheduled to begin in 2010 with an initial capacity of 27.5 billion cu m/year with gas supplied from Siberia. Capacity could be doubled with a parallel second line to be built in Phase 2.

In what appears to be recognition that Gazprom needs foreign deepwater operating expertise to develop the field, the gas monopoly announced that it had sent letters to the four companies on the Shtokman short list (reduced by the merger of Statoil and Hydro) offering them the possible opportunity to take part in the offshore development as contractors.2 Needless to say, the companies have not responded to this announcement with enthusiastic press releases. Nevertheless, Gazprom is expecting talks with the companies to recommence this month.

Russia had hinted prior to October 2006 that US companies Chevron and ConocoPhillips would, in any event, be left out of the Shtokman project if the US precipitates deterioration in trade relations between the countries, and the gas would be redirected away from the US to Europe. This is the type of political leverage Russia can bring to bear when it controls access to gas needed by other countries.

Yet North America is a potentially valuable market for Russian gas. Despite the decisions apparently made on the export route for Shtokman gas, it remains clear that Russia and Gazprom remain keen to export LNG to the US.

They continue to take positions to enter that market. Gazprom has set up a trading company in the US-Gazprom Marketing & Trading US in Houston. It planned to sell five or more LNG cargoes in the US in 2006 under swap or purchase-and-resale schemes, some of which have involved BP and BG. This author therefore believes that LNG export facets to the Shtokman-Nord Stream projects are likely to reemerge.

Maintaining leverage

Russia wants to retain as much control as possible over its energy resources and export infrastructure. By doing so it knows it will retain the power that enabled it to cut off gas to Ukraine in early 2006, and consequently to parts of Europe, in a successful attempt to double the price of gas to Ukraine.3 This tactic was successfully repeated in December 2006-January 2007 with Belarus. Such events must make potential customers downstream of Nord Stream-including North America-reflect upon their future security of gas supply and their potential vulnerability if becoming dependent on Russia for large volumes of gas.

With or without US company involvement in Shtokman, much of the LNG eventually produced by that project and Baltic LNG projects under discussion would probably be destined for North American consumption. What is clear, however, is that Russia sees the Shtokman and Baltic LNG schemes as an opportunity to leverage more concessions from North American and European companies. It remains to be seen whether any operators will be tempted to sign up as contractors to Gazprom, however.

Markets becoming wary

Despite its dominance as the main supplier of natural gas to Europe, Russia does not have it all its own way, and it certainly has established a credibility problem with some of its main markets. Many European countries are now uncomfortable about being so dependent on Russian energy supplies, particularly gas.

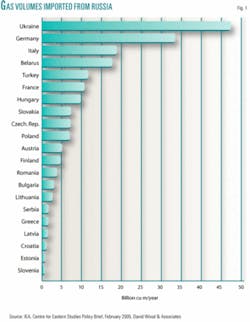

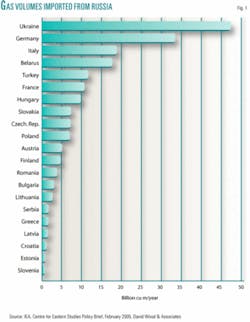

The major Western European consumers of Russian gas include Germany, which depends on Russia for more than 32% of its supply, and Italy and France, which depend on Russia for about 25% of their gas (Fig. 1). The dependence of Eastern European countries on Russian gas averages some 73% of annual gas supply, with Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia, and Slovakia being completely dependent on gas from Russia.4

Since the gas supply interruptions of January and February 2006 caused by Russia’s dispute with Ukraine, even Germany, Russia’s most prized gas customer in Europe, is seeking supply security in diversity. Like Russia’s other biggest customers, it is looking at alternatives to diversify its gas supply and guarantee supplies in the event of future pipeline disruptions.

Nord Stream is Russia’s preferred solution as it avoids Poland and Belarus (Fig. 2). Germany sanctioned this in 2006. However, German energy companies are now openly seeking LNG import supplies and may even build their own LNG receiving terminal at Wilhelmshaven in the near future.

Asian markets sought

Russia has the opportunity to develop the vast untapped natural gas resources of Eastern Siberia to supply China’s growing energy requirements and the thirsty markets of Japan and South Korea beyond.

It would seem commercially expedient for Russia to commence these multibillion dollar infrastructure projects as soon as possible with a careful pipeline strategy integrating capital contributions from these key Far East customers and international oil companies (IOCs).

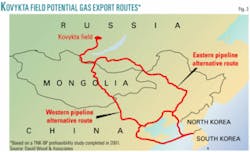

Indeed TNK-BP, as a holder of substantial stranded East Siberian gas reserves in Kovytka field, has been trying for several years to secure government approval to build a pipeline to China and potentially beyond to South Korea.

Kovykta field has gas reserves of 1.4 trillion cu m. A prefeasibility study has identified two potential routes for such a pipeline-an eastern route and a western route (Fig. 3). One, an $8.5 billion pipeline, would extend 2,645 km across Mongolia to Beijing and would include 22 compressor stations. The eastern option is a 4,485 km line extending across Ulan Ude and Chita to Beijing. This project would cost $10.5 billion and require about 37 compressor stations.

Each project has many engineering challenges associated with remoteness; varied terrain, such as permafrost, mountains, seismic zones, deserts, and wetlands; and protection of world heritage archeological sites such as China’s Great Wall. TNK-BP has major political challenges to overcome as well, particularly with Gazprom, if it is to bring this gas to market.

TNK-BP and Gazprom have discussed and disagreed over the preferred pipeline route for several years. The eastern option opens up opportunities to ultimately deliver gas to Japan, but it would cost more and take longer to build. The short-term opportunities in China’s gas market are what TNK-BP has been striving to unlock. In 2006 it was made clear that if such an export pipeline is to be built, it will be under Gazprom’s operatorship. And despite the commercial benefits this would bring to Russia’s East, the government has stated that work will not commence until after 2012 and will be under Russian control.

The delay makes little commercial sense but may be explained in terms of control and geopolitics. Imposition of such an export time frame devalues the reserves for publicly traded companies such as TNK-BP and makes it more likely that the reserves will end up in Gazprom’s hands at a low price in the medium-term.

Such maneuvering also inspires little confidence in the potential customers that they can expect Russian gas to solve their medium-term energy shortages. China is seeking LNG from a range of Far East suppliers and has entered into agreements with Iran for additional LNG volumes in the medium-term. Japan already has a well-established, diversified LNG supply base and is unlikely to replace much of that with pipeline gas from Russia unless very attractive, reliable, long-term prices are offered, which seems unlikely in the current energy market.

The Rosneft IPO case

In July 2006, Rosneft’s initial public offering (IPO) was thought by many to be simply laundered assets of the Russian government’s appropriations from Yukos, an existing publicly traded company. The flotation, with shares priced at $7.55, was one of the largest in history behind those of Japan’s Nippon Telegraph & Telephone Corp. Mobile Communications Network (some $18.36 billion), Enel SPA, Deutsche Telecom, and Bank of China. The group raised $10.66 billion through the flotation, the biggest in Russian history, which valued the firm at $80 billion. Rosneft shares, traded on the London Stock Exchange, increased progressively in price to $9.50/share from about $7.50/share between September and December 2006 and were trading around $8.90/share on Feb. 9, 2007.

The controversy, including a failed, last-gasp UK court challenge by Yukos to prevent the IPO from proceeding, concerns Rosneft’s acquired Yugansk oil unit. Rosneft bought Yugansk in 2004 after it was seized from Yukos and auctioned off to settle a disputed unpaid tax bill. Yukos has been gradually dismantled over the past 2 years and is in the middle of bankruptcy proceedings in Russia. Indeed, Andrei Illarionov, one of Putin’s own economic advisors, referred to the affair as the “robbery of the century.”

The initial price tag for the shares was above market expectations, ignoring the risks of investing in a country where the rule of commercial law can be flouted for purposes of political expediency. Yukos essentially lost its fight to survive on Sept. 19, 2006, when a Moscow arbitration court of appeal upheld an Aug. 1 court ruling declaring it bankrupt.

Many believe that it was the overt political ambitions of Mikhail Khodorkovsky, the jailed founder of Yukos, which led to the dismantling of this company, formerly Russia’s biggest crude oil producer. Russian authorities argue that Yukos was guilty of huge fraud and tax evasion and that they pursued it rightfully for money owed to the state. The problem with this argument is that the Russian government did not pursue companies owned by other oligarchs with similar histories and accounting practices.

In these circumstances it is understandable that many foreign institutional investors declined to subscribe to Rosneft’s IPO. Some 50% of the uptake involved just four buyers-Malaysia’s national oil company Petronas, China’s CNPC, BP, and a group of investors represented by Gazprombank-and it was declared to be “oversubscribed.” This gave the IPO the appearance of a dressed-up private placement. The IOCs involved clearly concluded that the access to reserves granted by this opportunity outweighed the uncertainty of the government interventions and manipulations ahead, which could erode much of the future value they should expect from a holding in Rosneft.

Gazprombank purchased its $1.2 billion in Rosneft shares on behalf of three of Russia’s richest oligarchs: Roman Abramovich, Vladimir Lisin, and Oleg Deripaska. The participation of these oligarchs helped to ensure that the IPO was oversubscribed and to demonstrate that it had the support of a substantial sector of Russian business. In February Gazprom announced it had received concrete expressions of interest from large US companies in the acquisition of assets formerly owned by Yukos as court-appointed receivers prepare to liquidate its remaining assets. No US company has yet confirmed such interest.

There are few countries in the world in which the Yukos and Rosneft outcomes would not be challenged in a robust way both politically and legally. The precedent is disturbing. Because they succeeded with it once, and have been emboldened by the outcome, few can expect similar events not to occur in the future. Whenever the Russian government becomes short of funds in the future, say if an oil or gas demand or price collapse occurs, Russian publicly traded companies had better beware. Also IOCs with attractive assets linked with strategically important export infrastructure may have to negotiate hard and accept erosion in their equity participations in order to avoid appropriations. Caveat emptor!

References

- Clark, J.R., and Rach, N.M., OGJ, Oct 16, 2006, p. 20.

- www.mosnews.com, Jan. 26, 2007.

- Jovene, Cecile, OGJ, Mar. 20, 2006, p. 57.

- International Energy Agency; Centre for Eastern Studies Policy Brief, February 2005.