Part 1: Russia seeks global influence by exploiting energy geopolitics

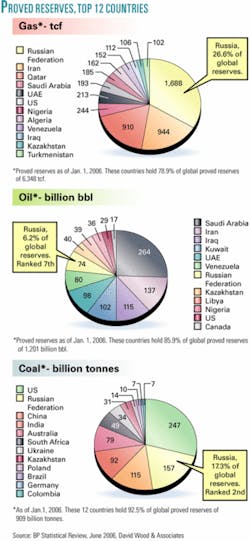

Russia is blessed with a significant share of the world’s energy resources. It is among the top five producing countries worldwide for all three fossil fuels: natural gas, crude oil, and coal (see table). Russia holds the largest proved gas reserves of any country in the world and holds the seventh largest proved reserves of crude, ranking just behind the six top Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries oil producers. In addition, it holds the second largest proved reserves of coal of any country worldwide (see figure).

Russia seems to be banking on energy exploitation and appropriations of these resources to reestablish its status as a world power. In doing so, however, it is showing few signs of avoiding several main pitfalls that have befallen other petroeconomies:

- It is taking few measures to avoid “Dutch disease,” the deindustrialization of a nation’s economy that occurs when the discovery of a natural resource raises the value of that nation’s currency, making manufactured goods less competitive with other nations, increasing imports and decreasing exports.1 The term originated in Holland after the discovery of North Sea gas.

- It has neglected to develop a progressive and stable taxation system that would prevent operating companies’ being forced out of business in adverse economic conditions.

- It has not restrained predatory nationalistic instincts to appropriate assets and frighten away foreign investment in the medium-term.

In Russia, energy resources seem to be considered more as weapons of political leverage and a means of enriching favored elites than as opportunities to benefit and develop wider Russian society.

President Vladimir Putin continues to exploit Russia’s strategic oil and gas export supply chains to extend its international diplomatic influence and power. Its control over key infrastructure supplying oil and gas into Western Europe provides it with more power in the prevailing global environment of booming commodity prices responding to perceived long-term tight supply.

Times have changed for this petroeconomy since the dark days of 1998, when oil prices were about $10/ bbl and gas prices were less than half what they are today, forcing Russia to default on its international debts. It now has the potential to achieve economic prosperity and to command the attention and respect of major energy consumers of both the Organization for European Cooperation and Development (OECD) and the developing world.

The increased petrorevenues and global influence that Russia now enjoys have maintained Putin’s popularity in Russia, even though he continues to recentralize power, erode Russia’s democratic institutions, and take privately held assets into state ownership at every opportunity.

However, there is international concern about the unsubtle policies that Russia and state-owned energy institutions such as OAO Gazprom now pursue to extend their sphere of influence internationally. These policies have been referred to aptly as “Russian Energy Imperialism.”2

If Putin stands down as president in 2008, he can claim as his legacy that he has reestablished state control of Russia’s energy resources. To do this, he has had to accept international condemnation at the dismantlement of Yukos. But in doing so he has positioned state-controlled Gazprom and OAO Rosneft firmly at the center of Russia’s petroleum sector.

Indeed in recent years Putin’s focus on diplomatic business overseas has been mainly related to Gazprom’s interests and expanding energy export infrastructure. It is not surprising that he has placed state management of natural resources at the center of Russia’s foreign policy. Since 1990, Russia has greatly diminished as a military power and has struggled to maintain its international image.

Putin was quick to recognize that energy resources offer a short-term opportunity to bolster Russia’s power on the world stage. However, the unsubtle tactics he has employed to pursue that strategy have taken the world’s energy consumers by surprise and raised alarms about becoming even partially dependent on Russian energy supplies. Hence, it remains uncertain whether this strategy will be effective in the longer term. Putting the export of energy resources at the core of Russia’s foreign policy now means that political, rather than market or commercial, issues determine decisions made on investments and alliances with international corporations.

Powerhouse Gazprom

Russia’s largest company, Gazprom, is the world’s largest gas producer, generating some 95% of the country’s gas and controlling more than 25% of the world’s gas reserves. Its barrel-of-oil-equivalent (boe) reserves are the third largest in the world, slightly behind Saudi Arabia and Iran and ahead of Iraq and Kuwait. Gazprom’s daily production is equivalent to 10.3 million bbl of oil, compared with Russia’s daily crude and petroleum product liquids exports of some 7 million bbl.

However, domestic efficiency is an issue for this institutional monolith. The gas prices Gazprom can charge its Russian customers remain below commercial thresholds due to the government’s longstanding subsidy policies. Gazprom’s gas prices are kept artificially low for their home market in order to bolster domestic support for the government. This policy depresses domestic profits and distorts commercial decisions for the company.

Notwithstanding such price benefits, many domestic customers fail to pay their bills, requiring Gazprom to subsidize its domestic commitments from revenues received from export customers, mainly in Western Europe. Hence Gazprom’s strategic focus remains very much on its exports.

The high level of government and corporate corruption throughout Russia is another key factor influencing Russia’s energy sector. Decisions often are based on how much they will enrich individual oligarchs, senior managers, or state officials rather than what makes commercial sense. What is more disconcerting is that Russians seem prepared to continue accepting staggering levels of corruption, extortion, and civil rights restrictions as a normal way of doing business. This system reduces reinvestment in Russia’s aging energy infrastructure, as powerful individuals-for personal and often frivolous use-remit huge amounts of the profits out of the country. Instead, Russia looks to foreign companies to make infrastructure investments in exchange for access, albeit on dubious terms, to energy resources.

Russian muscle-flexing as an energy superpower manifests itself in the form of hegemony over adjacent European and Asian markets and the Former Soviet Union states that this country’s export infrastructure transits. In particular, Russia seeks to manipulate and control countries-Ukraine, Belarus, and Poland-that have transit pipelines to Europe and to restrict the ability of Caspian states to export petroleum outside its sphere of influence.

Ukraine, Caspian states

Ukraine and the Caspian states seem to be caught between a bear and a rabbit. Over the course of the past year Russia has openly engaged in a “cold energy war” against Ukraine, with both political and commercial goals. It is attempting to wrest control of existing gas and oil pipelines transiting Ukraine as well as to dominate Ukraine’s domestic energy sector. It also is keen to block the development of pipelines from Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan in Central Asia to Europe, and particularly routes through Ukraine.

These Soviet-style aggressive tactics are not limited to Ukraine. Georgia in late September 2006 expelled a number of Russian diplomats amid accusations of spying and attempts to precipitate a coup. Georgia also has great strategic significance as a transit country from the Caspian region to Turkey. With the newly commissioned Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan (BTC) crude oil pipeline and the recently completed 42-in. South Caucasus Pipeline, it now has the ability to offer export routes for Caspian gas that bypass Russia.

Gazprom, negotiating from a position of strength, is reported to have offered gas price stability to Ukraine in return for a share in the country’s assets and control over its main gas pipelines. This harsh proposal implies that Russia will punish Ukraine with sharp gas price increases if it does not accede. Ukrainian President Viktor Yushchenko in response reaffirmed the country’s energy strategy seeking alternative gas deliveries from the Caspian states and participation in a project (initially from Azerbaijan) to deliver Caspian gas to Europe via a pipeline system that would bypass Russia.

Europe, itself short of gas supplies, is keen to bring in new supplies and diversify from Russian dependence but cannot afford disputes with Russia that could lead to supply interruptions.

Russia, in response to Ukraine-European plans to cut it out of new supply routes, is using its commercial and political influence in the gas-rich Caspian states to buy gas at prices above those offered by Ukraine. Gazprom commenced purchase of Turkmen gas for $100/thousand cu m in October 2006, commenting that it would not prevent Ukraine from being able to purchase its gas for $95/thousand cu m, provided it grants Russia control over Ukraine’s major gas pipeline infrastructure.

In May 2006, Russia offered to buy gas from Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan at prices exceeding $100/thousand cu m-much more than the prevailing price-in exchange for reassurances that the country would not build or send its gas through pipelines that would cut Russia out of its delivery network.

In September 2006 Gazprom signed a deal with Turkmenistan to buy 162 billion cu m of gas for $100/thousand cu m in 2006-09 with assurances that all gas exported will be delivered through Russia and that Turkmenistan is not interested in a trans-Caspian gas pipeline.

The US and Europe support a pipeline bypassing Russia, with countries such as Poland key to diversification from Russian gas supplies. Finance for this project could be raised in Europe and the US, as it was for the BTC line that has bypassed Russia in oil exports from Azerbaijan to Europe and beyond. It probably would require more than $10 billion.

The question is whether Russia’s political and economic grip over key Caspian states, beyond Azerbaijan where most of the gas reserves lie, is strong enough to prevent them from participating in the project. Russia has demonstrated that it will do all it can to destabilize countries along the pipeline route with divide-and-rule tactics.

International companies

International oil companies (IOCs) seem to be displaying a lemming-like mentality.

Russia is in the process of seducing key current and future gas markets, such as Germany, UK, China, Japan, and Korea, with strategic new pipeline links that have limited transit countries involved and that can provide gas consumers with long-term supply security.

Russia already has successfully seduced many major IOCs with the offer of access to huge reserves in return for capital investment in Russia and, more importantly, equity interests in key assets outside of Russia. It is positioning itself to control sufficient energy infrastructure in Europe to be able to reward or punish its gas customers, depending on the degree of their concessions and acquiescence.

The IOCs are attracted by access to reserves that will resolve their short-term reserves-to-production ratio problems, thereby being able to provide investors with impressive reserves reports. BP jumped in during 2002 through TNK-BP, and Total SA, Statoil ASA, Norsk Hydro ASA, and many US companies are competing to offer Gazprom assets to join in the apparent bonanza. It all unfortunately comes with strings attached and the growing suspicion that the Russian government ultimately will manipulate the taxation mechanisms to ensure that the IOCs make little or no profit from their investments.

Shell and ExxonMobil’s experiences in various phases of the Sakhalin field development, extending over the past decade, offer salutary tales for would-be investors.

Sakhalin Island lies in an excellent position to export oil and gas to Japan, Korea, China, and the US West Coast. LNG customers are already signed up in those markets for Shell-led Sakhalin-II LNG. However, the strategic importance of these reserves to Russia is such that Gazprom and Rosneft are manipulating themselves back into controlling positions. Gazprom now owns 50% plus one share interest in the project.3 Shell also faces court action and fines for alleged environmental infractions and has lost a $300 million second bank loan for the project.

Putin has managed to manipulate rules on foreign investment in “strategic companies” to secure state control. On the other hand, IOCs holding attractive infrastructure and customer bases in Russia’s markets remain vulnerable to takeovers from the Russian state-owned giants. Rumors of Gazprom’s interest in UK gas distribution and marketing group Centrica have persisted since 2005. European and national governments in Europe will find it hard to resist such moves on legal grounds. This makes Western European companies vulnerable to Russian energy expansionism even if they do not hold assets in Russia.

US strategy frustrated

As a superpower, the US is becoming weaker in the global energy sector. Even if more reserves in giant deepwater fields can be found in North America, they remain eye-wateringly expensive to develop and produce compared with oil and gas reserves in OPEC countries and Russia. This provides Russia with a tool to exploit in its efforts to redress the international power balance, which has so firmly swung in favor of the US, and Russia has not been slow to use it.

US tolerance of Russia’s recent lurch towards undemocratic behavior and business practices, particularly with respect to free market enterprises, is in itself a recognition that Russia can play a pivotal role in global energy supply and future energy security for the US. Having Russia’s energy resources available, to act as a foil against potential supply interruptions precipitated by OPEC policies as several of its members harden their anti-US-OECD stance, is a good reason for OECD countries to establish and maintain good relations with Russia.

In 2006 across the Middle East region, sectarian violence persisted in Iraq; Iran continued to pursue its nuclear ambitions; open hostilities erupted between Israel and Lebanon and between Israel and the Palestinians; and Taliban offensives, launched from Pakistan, were renewed in Afghanistan. These heightened tensions across the Middle East, where some 60% of the world’s proved petroleum reserves reside, suggest that the US is unlikely to precipitate further instability in world energy supplies by confronting Russia’s expansionist and bullying energy strategy in the near future.

And in the current geopolitical environment, it is difficult for OECD countries to put diplomatic pressure on Russia by exposing its imperialistic tactics. When OECD politicians make comments about deteriorating democracy, corruption, and human rights directly to Putin, his response is usually a shrug and, avoiding a direct response, to make reference to Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq, the Guantánamo Bay detention center in Cuba, and incidents such as the “cash for peerages” scandal and poor ethical standards displayed by some UK government ministers. His point is that the US, UK, and other G8 economies should put their own houses in order before dictating to Russia how it should behave.

However, US resistance to Russian accession to the World Trade Organization and sanctions on two Russian arms companies for alleged supply of arms to Iran have raised tension between Russia and the US. Russian responses in September 2006 were to imply that such actions would lead to restrictions of access to mineral resources by US companies. Russian authorities recently cancelled environmental approval for the Sakhalin-2 LNG project, the $22 billion Shell-led project already more than 100% over budget, and failed to accept Exxon’s cost revision for the Sakhalin-1 project. Both of these are projects operated under production-sharing terms, which the Russian authorities wish to modify into standard Russian taxation terms now that billions of dollars of investment have been sunk into the projects.

Other major IOCs are suffering obstacles and problems raised once initial investments have been made; Total and TNK-BP also are facing the threat of withdrawn environmental permits. Last month Russia alleged environmental violations in huge Kvoykta gas field, raising fears that BP might lose control of that project (see Part 2). These maneuverings by Russian authorities are focused on either improving the government take from the projects or outright assets appropriation.

This month Russia and Iran, together holding 41.5% of the world’s gas reserves, discussed how to create an OPEC-like cartel for gas, a move sure to unsettle global gas consumers.

Part 2 of this article will appear in the Feb. 19, 2007, issue.

References

- OGJ, Nov. 6, 2006, p. 18.

- Economides, M.J., energytribune.com, Sept. 13, 2006.

- OGJ, Jan. 2, 2007, p. 29.

The author

David Wood ([email protected]) is an international energy consultant specializing in the integration of technical, economic, risk, and strategic information to aid portfolio evaluation and management decisions. He holds a PhD from Imperial College, London. Key elements of his work are research and training concerning a wide range of energy-related topics, including project contracts, economics, natural gas, LNG, gas-to-liquids, and portfolio and risk analysis. He is based in Lincoln, UK, but operates worldwide (www.dwasolutions.com).