POINT OF VIEW: PDO undertakes more complex production, development projects

During his 5 years as managing director of Petroleum Development Oman, John Malcolm has seen an increase in the complexity of operations for sustaining oil production from the company’s large Block 6 in Oman.

PDO produces oil and gas from about 3,750 wells in 120 fields and operates about 16,000 km of pipelines and flowlines, numerous oil production facilities, and three gas processing plants. In 2006, it used 36 drilling rigs to drill 249 oil wells in the complex geology of Oman that includes light and heavy oil accumulations in carbonates and sandstones, at shallow and deep depths. Its 2007 program calls for drilling about 400 wells.

In 2006, PDO produced an average 589,000 bo/d, which was about 7% less than in the year before. Its natural gas and condensate production during 2006 was 430,000 boe/d. The company expects to produce 560,000-570,000 bo/d in 2007.

Owners of PDO include the Omani government 60%; Royal Dutch Shell PLC 34%; Total SA 4%, and Partex Oil & Gas Group 2%. In December 2004, PDO signed a 40-year extension of its concession and shareholder agreement for Block 6, which was to expire in 2012.

The shareholders of PDO have an equity stake in the oil but not the nonassociated gas resources in Block 6. The company, however, produces and explores for nonassociated gas on behalf of the Omani government under a separate agreement.

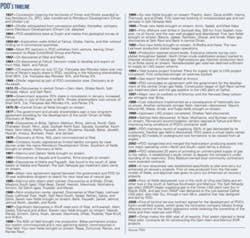

The company’s first commercial oil discoveries were in the early 1960s, with first oil exported from Oman starting 40 years ago in 1967 (see timeline in accompanying box). PDO’s oil production peaked at an average 846,000 b/d in 1997.

Reservoir complexity

Malcolm said as fields in Oman have matured, PDO has started relying on a wider range of development options and operational strategies for ensuring long-term production capacity.

As a gross generalization illustrating the change, Malcolm said that during the 1970s to mid-1990s PDO was highly successful in finding and developing new accumulations. “Find them, drill them, and hook them up quickly.” Also during this time various optimization technologies, secondary recovery, and the use of 3D seismic tremendously helped reach record oil producing rates, he said.

By the mid-1990s, Malcolm noted “PDO stopped finding fields that could be easily hooked up.” For instance, in 1997 it found Harweel, the first in a cluster of high-pressure, sour-oil fields at depths ranging between 3 and 5 km. For such fields, the time between finding, appraisal, developing, and producing has increased because of their complexity, he said.

As discussed in more detail in the article, on p. 56, describing some of PDO’s planned enhanced oil recovery projects, the company will be injecting miscible sour gas to produce the cluster of fields near Harweel. To bring these fields on stream, PDO needed about 5 years of study, which included 3 years of development and production during Phase 1. Currently under construction is the $1 billion Phase 2AB of the project that will start producing the cluster of eight fields containing 10 intrasalt carbonate reservoirs.

PDO expects the Harweel cluster production to reach 60,000 b/d in 2010, with the potential to increase to 100,000 bo/d in the next decade.

Malcolm said that “if we had sweet reservoirs, we wouldn’t be doing what we are doing.”

Besides miscible sour-gas injection, PDO now is pursuing a host of other enhanced oil recovery projects that involve steam and chemicals for producing more of the company’s estimated 50 billion bbl of oil initially in place, about 15% of which already has been recovered.

With the long-term in mind, Malcolm said, “We have been working closely with several parties that have proven EOR experience, including the Shell EOR center of excellence now established in Oman. Although EOR may still be regarded as being in the distant future by many oil companies in the region, it is inevitable. Oil fields-even prolific ones-are eventually going to need thermal, chemical, or gaseous means of extracting oil.”

Field evaluations

In 2003, PDO established a study center for providing a better understanding of the company’s reservoirs. Malcolm said that the center has completed studies on about 70% of the oil initially in place in PDO’s 120 fields and is at a stage where it will start reassessing some field development plans.

The studies look at the future of a field for at least the next 5-10 years so that PDO can make decisions on proper technology for improving the field performance.

Staffed initially with mostly expatriates from Shell, the center’s staff now is 30-40% Omani. The work is done by integrated teams of reservoir engineers, geologists, petrophysicists, well engineers, and petroleum engineers.

“Doing things in country is very important, from both the country’s and company’s point of view. Links between the study center and assets are so much better than if separated by 1,000s of miles, allowing knowledge to move easier between them,” he said.

In the early 1990s, the production from the company’s existing fields with existing hardware declined at an average year-on-year rate of 10%, but this decline rate grew to 17-18% in early 2002, Malcolm said. In the past those decline rates could be more than offset by the production of “new” oil from additional reservoirs and additional wells, but that is no longer the case.

Still, with the better understanding of reservoirs, better reservoir monitoring and management methods, and better operational practices, the decline rate has been reduced even as the production water has increased, from 2 bbl of water/1 bbl of oil produced in 1992 to about 7-8 bbl of water/1 bbl of oil today.

In the next 5 years, PDO’s plans include expanding or initiating 15 waterflood projects; beginning in 2010, it will be completing one major field development project per year for the rest of that decade.

Contracting strategies

To gain efficiency, PDO has changed many of its contracting strategies. Malcolm said “Many things done 20 years ago in the way we contracted were appropriate for that time. But the last 20 years have seen massive changes and we have to look around for innovative contracting philosophy.”

For instance, PDO now contracts Chinese rigs and seismic crews as well as Indian hoists and continues to look all over the world for contractors that can work in an effective and safe manner, Malcolm said.

PDO also has started to do its own front-end engineering, to provide more flexibility in project construction, especially if the market changes, Malcolm said. One illustration of the effectiveness of doing work in-house is the company’s Qarn Alam thermal project, for which the bids last year came in too high. Because of its in-house work, PDO could divide the project into segments that could be managed by smaller contracting firms, at much less cost, Malcolm said.

The company also has started awarding service contracts for operating smaller noncore fields, although keeping equity ownership in the oil. Its first contract was signed in 2006 with MedcoEnergi International, an Indonesian company.

The service contract lets Medco and its partners accelerate development of a cluster of 18 small fields in the Nimr-Karim area of south Oman, so that PDO can devote more attention to its portfolio of large fields, Malcolm said.

PDO is now going ahead with a second such service contract covering the Rima satellite cluster, which produces 2,100 bo/d from nine fields. The contract also includes another nine undeveloped fields. PDO estimates that these fields contain 650 million bbl of oil in place.

Malcolm said such contracts “pull in a broad range of people from both small companies and service companies with the hope that they will have new bright ideas.”

PDO also has an active local community contracting program that gives local contractors a chance to bid on various projects. Malcolm noted that one local contractor that began building fences for PDO many years has now grown into an international company that recently had an initial public offering of its stock.

Career highlights

John Malcolm has been managing director of Petroleum Development Oman (PDO) since November 2002.

Employment

Malcolm in 1975 began his industrial career in the British heavy chemicals industry with positions in process control systems, project engineering, and operations-maintenance. In 1981, he moved to the Middle East and worked on engineering upgrades for a major refinery. After a 2-year break from industry to engage in teaching, research, and consultancy at Heriot-Watt University in Edinburgh, he joined Shell in January 1986.

His first position with Shell was in PDO, as the head of instrumentation and process control. Later, he became the head of central engineering at PDO. After 2 years in Oman, he was assigned to Shell’s central office in the Hague, working on front-end prospect engineering, operational reviews, and a major standardization drive within Shell EP.

Next, he joined Shell Exploration & Production (UK) Ltd. in Aberdeen where he was a project manager for several engineering projects before returning to Shell’s Hague office to work on redesign, transition, and management of Shell’s Research and Technology center. He later held the position of vice-president.

This assignment was followed by an appointment as deputy director for the Far East and Australasia.

In 1999, Malcolm became general manager of Al Furat Petroleum Co.-a Damascus-based joint venture of Syria Petroleum Co., Shell, and Petro Canada. Later he was also appointed as the general manager of Syria Shell Petroleum Development.

In late 2002, he returned to Oman as managing director of PDO.

Education

Malcolm has a BSc in electrical and electronic engineering and a PhD in process control engineering, from Heriot-Watt University, Edinburgh.

Affiliation

Malcolm is a Fellow of the Institution of Engineering and Technology (FIET).