Does an $80/bbl oil price pose a threat the economy? Not necessarily, according to the president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas.

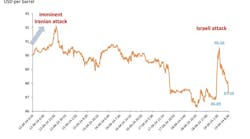

“Oil prices have been on a steady climb in recent years, tripling since early 2003 and breaching $80/bbl last month. This worries many people who remember the energy crises of the 1970s and the ensuing recessions. In fact, nine of the 10 post-World War II recessions were preceded by sharply rising oil prices,” Richard W. Fischer told the Charlotte (NC) Economics Club. “I will remind you, however, we have had several episodes of sharply rising oil prices in the past 15 years without recessions.”

In what Fischer called personal observations and not official policy, he differentiated short-term oil price swings from long-term supply and demand fundamentals. Instead of ignoring energy prices because they are dropped from the core inflation index, he picks them apart to understand their recent climb. His first question is whether a price run-up resulted from reduced supply or increased demand.

Different responses

“If it is reduced supply, like most of the oil price shocks prior to the mid-1990s, slowing economic activity and higher overall prices are likely. If the oil price increase is the result of a demand shock arising from productivity gains, however, we could see expanding economic activity and reduced inflationary pressures,” Fischer said.

The US economy has recently responded to rising oil prices with continued growth in the gross domestic product, declines in unemployment, and relatively moderate price pressures, he continued. Consumer spending and consumer confidence have remained strong, while business investments have expanded. Economic growth overseas has not been derailed, which has kept demand for US exports healthy.

Economic research has suggested that factors including a lower energy-to-GDP ratio, experience with oil price shocks, and trading of energy derivatives, which reduce the need for physical inventories, may explain recent economic resilience, Fischer said. But he suspects there may be another reason.

Stronger demand

“For a few years now, some economists have suggested that the US economy ought to respond differently to rising oil prices if the increase is the result of stronger demand for oil needed to fuel an expanding US economy rather than a result of diminished supplies,” he said.

A productivity shock originating in the US will boost domestic output and pull up the price of oil. Monetary policy that holds the nominal growth of GDP constant will reduce inflationary pressures. Economic expansion in India, China, or elsewhere will increase that country’s oil demand but also can raise its productivity, affecting the US as lower prices for imported goods and technological gains.

“As long as this continues, we can expect to see an expansion of output and lower overall prices, even as the world price of oil rises. A vicious cycle is, in a sense, almost transformed into a virtuous cycle,” Fischer said.