China fills first SPR site, faces oil, pipeline issues

After 10 years of indecision, China is building a strategic petroleum reserve (SPR) to protect against possible oil supply cutoffs and is addressing the companion issues of securing sufficient oil and improving the country’s pipeline and refining infrastructure to accommodate the reserves.

From 1993 until Hu Jintao’s accession to power in 2003, the “build” and “don’t build” factions’ debate raged within China over the merits of an SPR. This debate likely was prolonged by China’s lack of a powerful central energy ministry that could control the various government bureaucracies, state oil companies, and other stakeholders who compete to shape China’s energy policy. China’s Ministry of Energy (1988-93) was dissolved after energy producers incorporated in 1988 and refused to work with the new ministry.

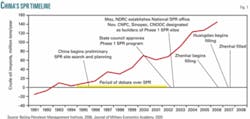

In 2004, however, Chinese companies began building four Phase 1 reserve sites. In 2006 China commenced filling the first site at Zhenhai, which reportedly was completed in June of this year.

Chinese firms also are improving the pipeline and refining infrastructure essential for utilizing SPR oil during a crisis. Fig. 1 provides a timeline of China’s SPR plans.

Challenges

However, China also is facing important challenges in planning its SPR, including:

- High construction, storage, and oil acquisition costs.

- The need to formulate SPR management guidelines.

- Criticism for driving up world oil prices. This has created a vicious circle in which Chinese decision-makers found that opacity and transparency both lead to condemnation, and they ultimately chose opaque SPR oil acquisition practices.

Some Chinese analysts believe that an SPR can be used to control oil price swings. If China uses its SPR for price management, however, it would create conflict with the International Energy Agency (IEA), which helps govern the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development countries’ stockpile use. At the December 2006 Five Country energy ministers’ meeting in Beijing, Chinese officials said the SPR would not be used for price management. A June 17 report from Xinhua Financial Network News, nevertheless, notes that 30% of the SPR’s capacity may be leased out to commercial firms. If so, commercial and strategic storage space should be kept physically separate, or else pressure could arise to manipulate stockpile levels in response to price concerns.

High costs and other factors may drive China to adopt a more flexible SPR management system than that used by Japan and the US. China’s SPR is still a work in progress and is characterized more by a “crossing the river by feeling the stones” approach than by a coherent national policy. This analysis attempts to arrange the “stones” by examining the following aspects of China’s SPR development:

- China’s current SPR construction status.

- Possible operational models.

- Potential methods of SPR financing and management.

- Sources of oil for China’s SPR.

- SPR connections to broader refining and pipeline systems.

- Key unresolved issues.

Current status

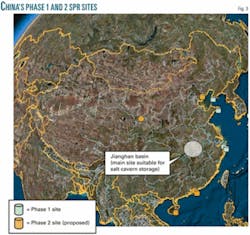

China’s SPR is being constructed in three phases. In Phase 1, due to be completed by yearend 2008, some 100 million bbl of crude oil will be stored at Dalian and Huangdao, in Shandong, and Zhenhai and Zhoushan in Zhejiang province, roughly 150 km from Shanghai. Zhenhai has taken cargoes from Russia and the Middle East, and Zhoushan is injecting crude from the Middle East and Africa-particularly Angola, Iran, and Sudan-as well as local production from Bohai Gulf and Liaohe fields. The Huangdao reserve is almost certain to begin filling by yearend unless oil prices spike. The Dalian SPR site is set to be completed in 2008. Fig. 2 provides details on the status and capacities of the four Phase 1 SPR sites.

April 2007 data showed a disparity of more than 600,000 b/d between China’s crude oil imports and refinery throughputs. While some of this gap may be attributable to spotty data, it is likely that a sizeable proportion of this oil flowed into commercial and strategic stockpiles. China’s SPR fill rate is price-sensitive, and the final authority to purchase crude for the reserve lies with the State Council.

Phases 2 and 3 will bring China’s strategic crude holdings to 300 million and 500 million bbl, respectively. Sites are still being determined. The port of Caofeidian on the Bohai Gulf 120 km northeast of Beijing apparently has been selected as a Phase 2 reserve base. Caofeidian will be able to accommodate very large crude carriers (VLCCs) and will be located near substantial refining and petrochemical projects. It also lies near the giant new Jidong Nanpu oil field, which by 2010 could be producing 200,000 b/d.

China is considering a Phase 2 SPR site in Northwestern Gansu province, which could be fed with crude piped in from Kazakhstan and Xinjiang. It would lie near Lanzhou, which has a large refining capacity. The cities of Nansha and Bao’an in Guangdong province and a site on Hainan Island are also on the Phase 2 short list. China does not appear to have begun formal selection of Phase 3 sites. Fig. 3 shows Phase 1 SPR sites and projected Phase 2 sites.

Operational models

As Chinese analysts consider models for China’s SPR, they primarily look to the US, Japan, and South Korea

- US model. The fully government-funded US SPR consists primarily of 62 solution-mined caverns in salt domes along the Texas and Louisiana Gulf Coast that can store up to 727 million bbl of crude. DynMcDermott Corp. manages these sites on behalf of the US Department of Energy at a project management office in New Orleans.

US SPR management policies are conservative. The president can order a “full drawdown” of the SPR to offset a severe oil supply disruption caused by an interruption in imports, interruptions in domestic oil supplies, or an “act of God,” such as floods, hurricanes, or other disruptions. He also can order a limited drawdown to cope with less serious interruptions that would have deleterious economic effects. Limited drawdowns cannot exceed 30 million bbl, last more than 60 days, or take the SPR inventory below 500 million bbl.

The US secretary of energy has the authority to conduct test sales of less than 5 million bbl and use exchanges to introduce higher-quality crude into the SPR or help oil companies resolve delivery problems. If a ship accident blocks a channel, for example, a company can borrow or exchange crude with DOE to forestall refinery shutdowns and then return an equal volume plus an exchange premium within 1-6 months.

As of June 20, 2007, private oil companies operating in the US maintained crude and product stocks of roughly 340 million bbl, but these stocks are intended to cover commercial demands, and they provide far less forward coverage than the SPR. Unlike Japan and South Korea, the US has no mandatory commercial stockpiling.

- Japan. Japan uses a hybrid stockpiling system in which the government stores 292 million bbl of crude in tanks and mined rock caverns at 10 national petroleum stockpiling bases and tanks leased from private firms. Private companies are required to store a minimum of 70 days worth of oil imports. Roughly half of this is stored as crude oil and half as oil products. As of March 2006, the combined government and private stocks provide 168 days of import protection. Japanese SPR drawdown standards are considered to be even more rigid than those of the US.

- South Korea. Korean National Oil Co. (KNOC) currently stores roughly 78 million bbl of crude, while private Korean oil companies must maintain 40 days of forward coverage for domestic supplies. Korean oil stockpiling is funded by duties imposed on petroleum imports. Through KNOC, the Korean government takes a liberal approach to stockpile management, using measures such as joint oil stockpiling and “time swaps.” Joint stockpiling means that KNOC leases storage space at 65¢-$1.00/bbl/year to petroleum producing countries in exchange for the preemptive right to purchase the stored crude in the event of a supply disruption.

China’s approach

China appears to be pursuing a state-private SPR system. National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) head Ma Kai says the commercial oil stocks of China National Petroleum Corp., Sinopec, and China National Offshore Oil Co. Ltd. will all play a role in China’s SPR. As of June 2007 these stocks provide about 21 days of forward coverage. According to some sources, NDRC wants China’s SPR to be run like the state grain and cotton stockpiles, which are managed by dedicated state-owned management companies who “manage autonomously and bear sole responsibility for profits and losses.” One key difference is that the strategic petroleum reserve will be far more centralized than the grain and cotton reserves, which have management at the provincial, county, and city levels.

Recent events, such as the Xinhua report that China may allocate 30% of its SPR capacity for private companies’ use, indicate that China may be incorporating commercial stocks into its SPR. It remains to be seen whether such reserves would be dynamically managed as in South Korea, or simply stocks that companies are forced to hold, as in Japan.

Under new rules promulgated by the Ministry of Commerce, Chinese crude oil wholesalers must now maintain at least 200,000 cu m (1.26 million bbl) of storage capacity, 50 times more than the previous requirement of 4,000 cu m.

Companies are preparing for their oil storage role. Sinopec is building more than 100 large oil storage tanks, adding to its 400 existing 30,000 cu m tanks and giving it the ability to store more than 15 million bbl of crude. In addition, Sinopec is setting up a central oil reserve management unit that will be the first of its kind among China’s national energy companies (Fig. 4).

In 2004, China created an SPR office within the NDRC’s Energy Bureau. However, little specific information has been released. Also, it is unclear what role the Ministry of Commerce may have in running China’s SPR.

Trevor Houser of China Strategic Advisory notes that the Zhenhai reserve appears to be operated more like a commercial storage facility than a US-style SPR, as Sinopec appears to be leasing tank space from the government. One advantage of having integrated oil companies operate the sites is that they will store appropriate crude streams for local refineries. In addition, regular inventory draws help maintain oil quality because oil stored in tanks needs to be circulated periodically.

If SPR site managers truly bear responsibility for profits and losses, they may be pressured to maximize returns by selling oil when prices are high and acquiring it when they fall. In essence, the SPR could eventually be run like the storage tanks used by traders in Cushing, Okla., rather than like a true strategic reserve. As such, China’s new energy law will need to include restrictions on drawdowns in situations other than major supply disruptions. This could ensure inventory maintenance while reducing the incentive to manipulate prices.

SPR finance

China’s SPR likely will combine commercial and government stocks because China may be unable to afford a US-style, fully government-funded SPR. The US has spent a total of $22 billion on its SPR. Of this, $5 billion was for facility construction and $17 billion for crude oil acquisition. US strategic reserves were purchased at an average of $27/bbl.

China is storing its Phase 1 reserves in aboveground steel tanks, which cost several times as much per barrel as solution-mined salt caverns. China also did not begin stockpiling oil until prices were already at $50/bbl or more. At the Jan. 29, 2007, Petrostock conference, Pei Jianjun, division chief of NDRC, noted that due to the high costs of building an SPR, China will need to establish stable and diversified long-term funding sources. Pei suggests central government financial allocations, state bank loans, and commercial lending. Some observers have suggested that China could use its $1 trillion-plus foreign exchange reserves to purchase oil for the SPR. However, People’s Bank of China Vice-Governor Wu Xiaoling has said the central bank cannot directly use China’s massive foreign exchange reserves to purchase energy assets, including oil for the SPR.

Funding options

Beijing currently tacks a 17% value added tax onto fuel oil imports and might consider adding duties for other imported products and crude (currently subject to a 5% export tax) to fund SPR oil purchases. Japan and South Korea use petroleum import duties to help fund their SPRs.

China could also tax coal production to help fund the SPR. The NDRC says that Chinese coal demand could hit 2.5 billion tons in 2007. Thus, assuming that half of this amount can be taxed, imposing a Y10 ($1.32)/ton coal tax could raise Y12.5 billion ($1.65 billion)/year, providing sufficient funds to purchase 70,000 b/d of oil for the SPR, assuming an average price of $65/bbl. Wholesale coal prices in China typically are Y220-320 ($29-42)/ton, so the tax would represent a 3-5% cost increase.

A coal tax would also promote environmental objectives by increasing the costs of coal usage, and because it helps fund the national SPR, Party officials could deflect criticism by framing the tax as an essential component of China’s national energy security. Similarly, fuel oil taxes could help promote clean fuel use by raising the cost of fuel oil and would also help China’s customs service capture revenue lost to unscrupulous oil importers who bill their cargoes as “fuel oil” to avoid crude oil import duties.

Imposing new taxes would pose formidable political and administrative challenges. However, because coal and fuel oil use is so widespread, the costs could be distributed among many different importers, producers, and consumers. The large volumes of coal and fuel oil consumed also mean that even if a sizeable amount of imports and consumption evaded the taxes, funds collected could still offset a substantial portion of the SPR’s cost. The taxes could be lifted or reduced once the SPR is filled.

Transport issues

For an SPR to be most effective, it must be able to rapidly release oil into a well-developed pipeline and maritime transportation system linked to substantial refining capacity. Partly because of this, the 11th 5-year plan for energy development emphasizes creating a national oil and gas pipeline grid. Robust capacity to shift oil supplies rapidly between major demand and import areas would introduce a degree of redundancy in case an incident closed one or more major ports capable of serving VLCCs. By 2010, Chinese companies plan to expand the country’s pipeline network for oil, gas, and products to 65,000 km from 40,000 km. Table 1 shows major Chinese oil pipeline projects.

The tanks for China’s Phase 1 SPR are relatively quick and simple to build and are the primary choice for areas lacking geological structures suitable for large-scale underground storage. The disadvantages of using tanks include high storage cost, exposure to high steel prices, the need for relatively large land areas, and vulnerability to natural disasters and attack.

For Phase 2 and 3 SPR sites, Chinese planners are considering underground facilities. Geological constraints-the lack of US Gulf Coast-type salt domes-will force China to use mined rock caverns. Experts at the US Geological Survey indicate that the only location in China where salt beds would be thick enough to leach out 1,000-2,000-ft tall US-style storage caverns would be the Jianghan basin near Wuhan, more than 600 miles from the sea. There appear to be no major underground salt beds or domes near the major oil import and demand centers along China’s East Coast.

China also has considered future commercial storage in which a major oil producer would acquire storage capacity in China and then sell China a call option for strategic oil release in case of a supply disruption. Both Saudi Arabia and Iran have discussed such deals with China, and Saudi Aramco apparently is prepared to build a 30 million-tonne (205 million bbl) commercial storage facility on Hainan Island. This would tie into broader Saudi moves to promote Chinese demand for Saudi oil by investing in new refineries designed to accept Saudi crude, which is often heavier and more sour than traditional Chinese crude streams. Future storage of sour OPEC crudes would mesh well with China’s moves to increase sour-crude refining capacity.

Table 2 shows the costs and benefits of above-ground tanks, mined rock caverns, solution mined salt caverns, and other SPR storage options.

Crude sourcing

NDRC senior consultant Zhou Fengqi said in mid-2006 that China intended to avoid upsetting world oil markets by choosing to use equity production to fill the SPR rather than purchasing oil on the spot market. Equity barrels would come either from joint ventures of Chinese oil companies and Western firms working in China, such as in Bohai Bay, or from Chinese production in overseas areas such as Sudan.

However, the ultimate price effect would be the same for each choice because using equity oil, term contracts, or spot purchases would all have the same net effect on Chinese demand and overall world oil demand. According to Xinhua, the Zhoushan SPR is being filled with a mixture of Middle East oil and crude from Bohai Bay and Liaohe oil fields. Zhenhai likely used a similar crude mix and has taken sour cargoes from Russia and the Middle East. Using domestic production to fill an SPR is not unprecedented, as the US often injects royalty production from Gulf of Mexico into its SPR. It is unclear if the Chinese government provides oil companies with incentives for making domestic production available to the SPR.

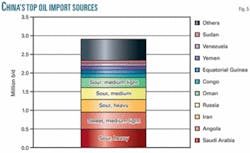

Fig. 5 provides a partial list of Chinese SPR shipment sources as well as the basic characteristics of China’s primary oil import streams.

Beijing’s oil taxation policies will determine where future SPR oil originates. A number of Chinese analysts suggest dropping duties on oil imports bound for the SPR, as well as providing other financial incentives for directing oil to the SPR. China might also consider adopting a royalty-in-kind (RIK) policy where, instead of tax payments, companies make an equivalent value of their oil production available to the Chinese SPR. Such policies could make equity oil a prime SPR fill stream. On the contrary, without preferential or RIK policies, SPR crude will be sourced in the same fashion as other oil imports.

The composition of Chinese oil companies’ refining capacity may also affect SPR oil acquisition. The companies will match crude oil purchases with their refineries’ needs. Chinese sources claim that heavy and sour Middle Eastern crudes will fill tanks managed by Sinopec and Sinochem (Zhenhai, Zhoushan, and Huangdao) while lighter and sweeter crudes from West Africa will fill the Dalian SPR managed by PetroChina.

Chinese firms are planning to expand refining capacity by more than 1.25 million b/d by 2010. Much of the new capacity will have to handle sour and heavy crudes because such oil is cheaper to acquire and makes up an increasing share of global oil production.

Boosting demand

China’s SPR fill will add 100,000-150,000 b/d to global oil demand for years. And given its rapid oil demand growth, China may need to boost filling rates well beyond those levels if it intends to meet its goal of 90 days of import coverage by 2020. This could greatly impact the oil market at the margin, particularly if China continues to acquire much of its crude on the spot market.

If global oil demand in 2007-08 grows by 1.4 million b/d, China’s SPR fill could make up 10% of global demand growth. Compared with total world oil use of about 86 million b/d, 150,000 b/d may seem of small import. Yet in the context of an already tight oil market, that diverted supply could be important.

Price effects also could be exaggerated by the fact that SPR oil purchases will be lumpy, meaning that sometimes multiple cargoes will be bound for the reserve, while at others, none will.

If Chinese operators are transparent about oil purchases for the SPR, as the US DOE is, the market can incorporate that information and lessen the possibility of price spikes, although long-term prices may rise as a result. Many Chinese energy analysts seem to believe transparency will simply drive prices up, raise purchasing costs, and cause China to get blamed for high global oil prices. China’s policy thus far has been to acquire cargoes and then release the information later. China is in a tough position, and barring a major mindset change, its SPR crude acquisition will likely remain opaque.

Key questions

Key questions remain concerning China’s new SPR. Legal and regulatory issues in particular are being handled cautiously. A knowledgeable Chinese energy analyst interviewed by the author notes that many important SPR operational questions remain unresolved. Thus, questions for future analysis include:

- How will the SPR fit into China’s new energy law?

- What drawdown standards will China use? Will it abide by the IEA guideline of using strategic stocks to manage 7.5% of its greater supply disruptions, or will it develop an entirely independent system?

- How closely will China coordinate its SPR management policies with the IEA? There currently are consultative meetings, but no formal cooperation.

Now that China has made the decision to build an SPR and is taking steps to implement it, it remains to be seen how the program will evolve from this point and how the SPR will affect world oil demand.

References

A full list of references is available from the author.

The author

Gabriel Collins ([email protected]) is a research fellow in the US Naval War College’s China Maritime Studies Institute. He is a 2005 honors graduate of Princeton University. Proficient in Mandarin Chinese and Russian, Collins specializes in primary research of Chinese and Russian energy policy, maritime energy security, Chinese shipbuilding, and Chinese naval modernization. Collins is a member of International Association for Energy Economics and has published energy research in Oil & Gas Journal, Geopolitics of Energy, The National Interest, Hart’s Oil & Gas Investor, LNG Observer, and Orbis (forthcoming).