Despite recent production decline, Europe is still the world’s largest offshore oil and gas producer.

Although oil prices have remained high for nearly 3 years, and total reserves probably still exceed 100 billion bbl, the mature parts of the region such as the UK have become less attractive for the oil majors. However, opportunities still abound for small E&P company players.

Right down the food chain, home-grown European offshore contractors are winning business worldwide and so are the European stock markets--London has hosted the IPOs of a number of international oilfield service companies.

The following is an examination of the state of plays and prospects and highlights some challenges ahead.

Hidden gems

Although generally referred to as “the North Sea,” the offshore play is more correctly the North Western Europe Continental Shelf (NWECS).

The area includes the waters of several countries: Denmark, Germany, Ireland, the Netherlands, Norway, and the UK. However, Norway and the UK account for most of the action.

The Norwegian and Barents seas cover a large area of the shelf and continental slope off Norway, while the UK also has production from the Irish Sea and the Atlantic shelf west of the Shetland Islands. Ireland has gas production off its southeast coast and developments happening off its environmentally challenging western coast. This Atlantic basin is underexplored but contains a number of proven and emerging play types with potential for field developments in 500 to 2,500 m of water.

One key fact now differentiates the NWECS from other offshore producing regions-offshore oil and gas production is growing across the world but declining in Western Europe. This is due to a lack of major new oil and gas prospects in the North Sea, which is presently responsible for the bulk of the region’s production.

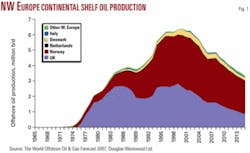

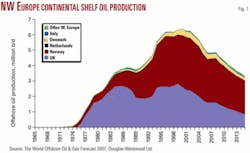

Offshore oil production in the NWECS region as a whole peaked at 6.4 million b/d in 2000, but the natural gas production peak of perhaps 232 billion cu m is unlikely to occur before 2010-12 (Figs. 1 and 2).

For Europe, a future of declining natural gas production from its offshore waters equates to increasing dependence on Russian and North African gas and raises considerable issues regarding security of future energy supply.

The fragility of the situation has been demonstrated when, in order to force former Soviet countries to pay more realistic prices, Russia’s Gazprom on Jan. 1, 2006, reduced gas supplies to the Ukraine and on Jan. 1, 2007, doubled the gas price to Belarus and Georgia. Then, on Jan. 8, 2007, in another price row Russia temporarily halted oil exports via Belarus.

The relevant giant gas pipelines are the same ones that feed Western Europe, and so does oil via Belarus. The result was political panic in capitals from Berlin to London. With 16% of the world’s natural gas reserves, Gazprom, in the words of London’s Financial Times, is now “a giant aware of its power.”

But off Europe, exploration and development continues, and despite the seemingly gloomy scenario of mainly small finds, exploration efforts still uncover some hidden gems even in the well-explored North Sea, and in Norway’s arctic waters fringing the Russian border, big games are in play.

UK sector

UK oil production peaked in 1999 at 2.8 million b/d and has since declined to below 1.5 million b/d. Annual gas production peaked in 2001 at 108 bcm/year and by 2006 had declined to 84 bcm/year.

As natural gas is a primary fuel for power generation, this has caused major concerns--and the fact this long-forecast situation seemed to have caught politicians by surprise is in itself remarkable. However, the past two winters were relatively mild, moderating gas demand. Then on Oct. 1, 2006, the 1,200-km Langeled subsea gas pipeline from Norway to the UK was opened-quite literally Norwegian gas saved Britain’s bacon and now boils its tea.

Offshore UK still has considerable numbers of small prospects to be drilled and small discoveries awaiting development, many suited to the smaller oil and gas companies that now dominate the offshore scene. According to the industry group “Oil & Gas UK,” since 1999 more than 30 new companies have entered the UK continental shelf with a commitment to invest in oil and gas assets. These companies now account for 38% of the industry’s total investment and 16% of production.

The emphasis is now firmly on developing the many small fields, but the current high costs of drilling and development is causing projects to be delayed. The negative impact of this cocktail of large costs and small plays was recently emphasized by Shell’s decision to sell some North Sea assets and scrap plans for a new £25 million headquarters in Aberdeen.

According to the industry group Oil & Gas UK, the average capital cost for a North Sea project begun in 2005 was about $8/bbl, with opex at $7. In 2007, capex is $15, opex $10. So with $70 oil on the face of it a high profit situation exists. However, about 45% of production is natural gas, whose price has slumped since the new Norwegian supplies came on line.

Historically, the UK has adapted its tax regime to changing times, but it is now in need of realignment to modern realities. To keep the show on the road, the new Prime Minister Gordon Brown needs to offer better fiscal incentives to E&P companies. Talks between the industry and the UK Treasury are ongoing.

Examples of current UK offshore field development projects include:

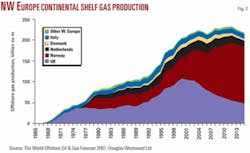

The Laggan discovery in the UK’s West of Shetland waters holds about 1 tcf of gas and lies in 640 m of water with a subsea development the most likely scheme. Total E&P UK PLC and partners are assessing the viability of building a new pipeline from Laggan directly to the St. Fergus gas terminal in Scotland.

The first of three planned appraisal wells was successful at nearby Rosebank/Lochnagar and could aid the development economics of the project (OGJ Online, July 19, 2007). Small fields such as Torridon, Laxford, and Victory could also be linked to Laggan’s infrastructure (Fig. 3).

Torridon field, also West of Shetland, is an important gas discovery in 700 m of water and operated by Chevron. An appraisal well was completed in April 2000. Torridon is possibly a floating production candidate, but there is no nearby infrastructure. Alternatively, it could also be tied back to Laggan.

Rosebank/Lochnagar is a large deepwater discovery currently being appraised. The field could contain 450 million to 500 million bbl of oil, making it one of the largest discoveries off Northwest Europe.

A major 2D-offset seismic shoot over Rosebank/Lochnagar is also planned. Chevron owns 40% of the equity in the field along with fellow stakeholders Norway’s Statoil with 30%, Austria’s OMV, with 20% and Denmark’s DONG with 10%.

Chestnut field, in shallow water on Block 22/2a, is being developed via a newbuild floating production unit, using Sevan’s SSP300 cylindrical design. Chestnut was discovered in 1986 and appraised by six wells. An extended well test produced about 1 million bbl of oil.

Full field production is scheduled for 2007 following development approval in 2005. The operator, Venture Production, has the option to use the vessel on another field after it is removed from Chestnut. The well, from the well test, plus a new subsea well will produce to the FPSO. The new well, depending on production levels, will be converted into a water injector at a later date.

Norway: the long view

Norway’s approach to its oil reserves has been very different from that of the UK.

With a small population and large offshore oil and gas production, its problem has been to manage the wealth that has been generated in such a way as to prevent offshore oil and gas, the country’s largest industry, from overheating the economy.

So in addition to a policy of carefully managed reserve development it has invested its national oil and gas profits to fund the pensions of this, and perhaps the next, generation.

There are still large parts of the Norwegian continental shelf which the Storting (Norwegian Parliament) has not opened up for petroleum activities, including all of the northern Barents Sea, Troms II, Nordland VII, parts of Nordland VI, coastal regions off Nordland, and Skagerrak.

Many of Norway’s future field development projects will be in remote arctic locations and in deep water, so have high subsea content. We estimate that Norwegian companies will spend an average of $4 billion/year on subsea developments for the next few years.

Although 52 fields are in production on the Norwegian continental shelf, the start-up of Statoil’s Snohvit field is no doubt a major milestone for Norway and Western Europe in general as it marks the region’s first LNG export terminal.

A key issue with the development was the hike in costs over and above the initial expected budget. This is a common problem across many LNG developments as contractor capacity is limited and raw materials prices soar.

The LNG business as a whole is a major growth sector and is forecast by Douglas-Westwood in “The World LNG & GTL Report 2007-2011” to see current expenditures of $11.5 billion, rising to $25.5 billion by 2011.

Norwegian developments include:

Due to start-up in 2007, Alvheim and nearby fields including Kameleon, East Kameleon, Kneler, and Boa are to be developed by Marathon. The development will employ at least 14 subsea wells in 120 m of water tied back to the FPSO. Gas export will be via the SAGE system.

Skarv field is thought to contain up to 500 million boe. BP has submitted a development plan for the field that includes a floating production unit with gas exported via an 80-km export line connecting to the Asgard Transport System. Skarv is due to start production by the third quarter of 2011. Nearby Idun field will be developed in conjunction with Skarv, and other surrounding finds may also be tied back to the FPSO in due course, including the overlying Snadd (gas) and Grasel (condensate) structures.

Statoil’s Gudrun structure is estimated to hold at least 150 million boe. According to Statoil, Gudrun could be developed either using a platform or as a subsea solution, with output transported to a Norwegian or UK installation for further processing and export. The field is on Block 025, about 40 km north of Sleipner and 13 km east of the Norway-UK median line. Statoil is the operator, partnered with Marathon, Gaz de France, and BP.

The Tyrihans complex is made up of Tyrihans North and Tyrihans South fields in more than 250 m of water. Tyrihans South, an oil field with a gas cap, was proven in 1983. Tyrihans North, a gas-condensate field with a thin oil zone, was proven in 1984.

Stolt Offshore was awarded a contract worth more than $83 million to lay two pipelines from the field to the Kristin platform. FMC was awarded a $216 million subsea contract which includes the supply of 13 subsea trees and five templates with manifolds, one of which will be used for seawater injection. Deliveries will take place in 2007 and 2008. Aker Kvaerner won a contract to provide subsea pumps for $32 million. Production is due to commence in 2009.

Technologies

The North Sea with its challenging environment was once the leading edge of offshore oil and gas and, encouraged by governments and driven by need, considerable funds were invested in new technologies to enable its development. This resulted in some successful commercial products and services, many of which are being applied worldwide.

Subsea processing is an area which in 2000 was seen as a niche sector of the market, with a small number of experts and evangelists driving the use of the technology forward. However, the change since then has been dramatic.

Now, subsea processing is being considered as an option by the majority of the larger oil companies on many of their new field development prospects and as an option to retrofit to existing fields. Even some of the smaller oil companies are now considering subsea processing.

The second edition of the Douglas-Westwood/OTM study, “The Subsea Processing Gamechanger Report 2006-2015,” surveyed more than 30 leading subsea experts from oil companies around the world and forecast that if operators’ performance expectations are met then over the next decade expenditure on subsea processing could in the ‘most likely’ scenario exceed $3.4 billion.

In the North Sea, the Norwegian sector is seeing some major subsea processing projects moving forward such as Tyrihans, Tordis, and Asgard, which will involve the use of various technologies including raw seawater injection, subsea separation, multiphase boosting, and subsea wet gas compression.

Multiphase metering is an associated enabling technology that has been successfully taken subsea by Western European companies such as Roxar and Framo. The application of such meters on a “one-per-well” basis is likely to become increasingly common as operators recognize the value in the detail and accuracy of data that these systems provide.

In another European success story, the FPSO business has seen the development and adoption of cylindrical units move ahead with the first Sevan Marine SSP-300 platform installed at Piranema field off Brazil and second heading for Chestnut field in the UK North Sea. Overall, the floating production sector is in fine health, with a total of $38 billion forecast to be spent worldwide in the next 5 years, according to the “World Floating Production Report 2007-2011,” Douglas-Westwood’s latest published study on the sector.

Corporate success

Facing a future of declining production in their home market, European oil and gas service sector companies are in hot pursuit of global business prospects.

European-grown companies large and small, ranging from Allseas (Netherlands) to MCS (Ireland), Kvaerner (Norway), the John Wood Group (UK), and Technip (France) are established in the key growth markets and are achieving notable successes both in the high technology and operational know-how sectors.

Some of this success is undoubtedly a result of many years of government encouraged R&D, but in other areas such as subsea operations European companies are also world leaders. Across Europe, various governments are encouraging their companies’ search for more international business, but some are more effective than others.

While the UK has suffered from constant changing of its government policies, the decimation of the Oil & Gas Division of its Department of Trade & Industry, and now the department itself, Norway has been taking the long view (OGJ Online, July 5, 2007). Its long-established oil and gas industry trade body INTSOK has partner companies encompassing the entire supply chain structure from its oil and gas companies to technology suppliers; but most importantly it is run by time-served oil sector executives. The overall result is that Norwegian industry is becoming very effective at winning foreign business by “hunting as a pack.”

As the UK’s main producer, Scotland is more focused on oil and gas than the UK central government with Scottish Enterprise heavily involved in the promotion of its companies and incentives such as the industry formation of the trade body Subsea UK.

A flood of money

Across the world, capital markets are awash with cash, with too much money chasing too few investment opportunities. With oil maintaining high prices, many generalist investors are seeking energy-related exposure and the result is that oil companies are usually fully valued, therefore European oil services companies have attracted attention.

In addition, the European stock markets are now driving oil services investment and sucking business away from Wall Street. This is partly due to the Sarbanes-Oxley issue, and the associated risks for IPOs are hampering US investment activity. With high oil prices delivering greatly enhanced profits, IPOs are attractive both as an exit mechanism for service company owners or for fundraising. With a large appetite from investors, we expect to see more international firms joining the London and Singapore exchanges.

Recent examples of the international diversity of highly successful IPOs on the London market include UK subsea flexible pipe maker Wellstream, which recently opened a plant in Brazil, and the Russian oil services group Integra.

However, another outcome is that oil service companies’ own desire for merger and acquisition is being outbid by institutional investors and we are still to see major group-building M&A programs by oil field services companies. Private equity is driving many transactions, both in private and public company sectors.

European future

With its main North Sea producing area in decline and the majors moving to pastures new, Offshore Europe is well into the process of becoming a very different region, dominated by small but potentially profitable players, the “puddle suckers.”

Yes, there will be big plays in future years, but mainly at the extreme environmental edges-the arctic and deepwater frontiers where big plays are essential to cover the very high costs.

But the North Sea itself was once the frontier and demanded great investments in the development of technological and operational expertise. The European technology and contracting companies that evolved now number among world-leaders. Europe is also home to some of the world’s leading financial centers, and this combination of capable contractors and world class financial engineering results in a region that is experiencing production decline but commercial growth.

Acknowledgments

The author acknowledges the contributions to this article from his colleagues Andrew Reid, director responsible for transaction services, Steve Robertson, assistant director and oil and gas manager, and Dr. Michael Smith, who manages the Energyfiles database.

The author

John Westwood ([email protected]) is the founder of energy analysts Douglas-Westwood. The firm, which acts as consultant to government agencies, oil and gas companies and contractors, and the financial sector, over the past 2 years has completed commercial due diligence on M&A and financing deals totaling $5 billion. He initially spent 12 years in offshore contracting in the North Sea, Southeast Asia, South America, and the US. He has since spent 22 years working on business research and analysis. He is the author of over 90 papers and is a regular speaker at industry events and investment seminars worldwide.