SPECIAL REPORT: Louisiana adds new reef sites for storm-damaged structures

Widespread destruction during the 2005 hurricane season in the Gulf of Mexico has led to Louisiana creating additional Special Artificial Reef Site (SARS) locations for disposing of some offshore structures damaged during the storms.

The Louisiana Advisory Council approves the establishment of these sites. During 2006, the council approved 10 projects representing 35 platforms as SARS areas within the Louisiana Artificial Reef Program (LARP).

Because the number of destroyed structures submitted for SARS review may have peaked, the project reviews from the 2005 hurricane season should finish by yearend 2007.

2005 hurricanes

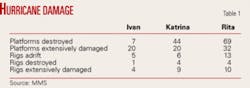

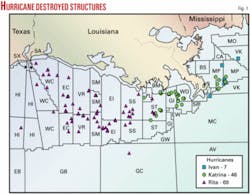

Hurricane Katrina destroyed 46 platforms and severely damaged 20 others, while Hurricane Rita destroyed 69 platforms and damaged 32 others (Table 1, Fig. 1). The storms also destroyed 8 drilling rigs and another 19 rigs sustained much damage.

The creation of the SARS program in 1991 within LARP has allowed companies to reef offshore infrastructure such as platforms, drilling rigs, and derrick barges destroyed by hurricanes or other unusual circumstances.

Louisiana created the SARS program initially to accommodate a drilling rig in South Timbalier Block 86 that collapsed during Hurricane Juan in 1985.

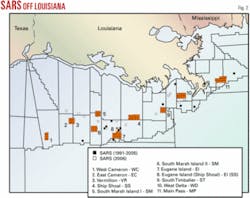

LARP has nine designated sites for disposition of offshore structures as artificial reefs (Fig. 2). Under normal conditions, a structure that falls outside these nine areas must either be towed to it or moved ashore.

For structures destroyed in hurricanes, SARS allows the LARP to establish reefs outside of the nine designated areas.

SARS approvals

State regulators must decide if a project submittal fits the SARS program based on:

- Would the destroyed structure benefit recreational or commercial fishing, or fish habitat at its current location?

- Would the site pose a threat to navigation or other users, or interfere with future oil and gas field development?

- Could the site serve as a biological field study or a location for future decommissioned structures?

Regulators evaluate the technical and environmental aspects of each project, and if the structure fails to offer benefits for the marine habitat, the structure owners will have to remove it in accordance with federal requirements.

Decommissioning platforms

A platform destroyed in a hurricane usually lies horizontally on the seafloor, as if the structure was pushed over on its side. In some cases, much of the structure may have been submerged in mud. Structural integrity of jacket components likely is unknown, increasing the risks for lifting operations. Complete removal also may not be technically feasible or may pose risks to divers that exceed acceptable limits.

If the structural integrity meets minimum thresholds, the platform then can be lifted and transported ashore or to a reef site; otherwise, the toppled structure requires cutting and removal in pieces or dismantling in a manner that satisfies clearance requirements.

Diving personnel or remotely operated vehicles (ROVs) have to cut and move debris to establish access to wells. Diver exposure may greatly exceed the time required in normal operations, increasing risks and costs. The divers also work in conditions with limited access and poor visibility.

Decommissioning tasks often are complex and require the design of new tools. ROVs can reduce the need for divers, but in most cases, ROVs cannot do all the operations required and are expensive to operate.

The cost for decommissioning a destroyed structure may be 5-25 times more than for an undamaged structure.

The petroleum industry has extensive experience in decommissioning offshore structures in the gulf, but only a small fraction of this work-about 5%-relates to removing structures damaged by weather.

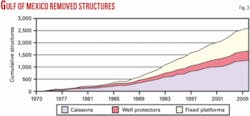

The industry, to date, has removed 1,286 caissons and 1,438 jacket structures from the gulf (Fig. 3), and for the past decade removals have averaged 136 structures/year.

Rigs-to-reef program

In 1984, US Pres. Ronald Reagan signed the National Fishing Enhancement Act (NFEA - Title II of Public Law 98-623) to “promote and facilitate responsible and effective efforts to establish artificial reefs ... constructed or placed for the purpose of enhancing fishery resources and commercial and recreational opportunities.”

The NFEA consolidated several decades of local and state laws and directed the National Marine Fisheries Service to develop the National Artificial Reef Plan to serve as a guide to state artificial reef programs. The NFEA also mandated the Secretary of Commerce and other support groups to develop a long-term plan for siting, constructing, permitting, installing, monitoring, managing, and maintaining artificial reefs within and seaward of state jurisdictions.

The US Minerals Management Service (MMS) adopted a rig-to-reef policy in 1985,1-2 and in 1986, the Louisiana Fishing Enhancement Act (Act 100-1986) created the LARP.3 In 1991, the Texas legislative established the Texas Artificial Reef Plan.

The industry has donated 147 structures for artificial reefs in LARP between 1987 and 2006 and 91 structures to the Texas Artificial Reef program between 1991 and 2006.

Regulatory requirements

Various government bodies regulate offshore structure decommissioning and abandonment. The regulatory body with primary responsibility depends on the structure’s location. State agencies are responsible for structures in state waters; the MMS is responsible for structures in federal waters.

Regulations in 30 CFR §250.1703 specify general requirements for decommissioning in federal waters and require, within 1 year after the lease or pipeline right-of-way terminates, permanent plugging and abandonment of all wells, removal of all platforms and other facilities, and clearance from the seafloor of all obstructions created by the operations.4

The same federal regulations that guide normal decommissioning operation apply to infrastructure destroyed by accident, terrorism, or natural catastrophe, but approval delays may occur, depending on the nature of the destruction and market conditions following the event.

Decommissioning decision

For a mature field with marginal production, an operator may not find it economically justifiable to repair or replace a damaged or destroyed platform. Several factors affect the decision to repair, replace, or abandon damaged and destroyed infrastructure.

For structures, the return on investment on fabricating and installing a new platform, subsea assembly, or pipeline interconnections depends on:

- Costs for removing and repairing the destroyed or damaged structure.

- Costs for plugging and abandoning wellbores.

- Costs for reentry and redrilling wells.

- Estimates of remaining reserves.

- Current and forecast commodity prices.

- Operating costs.

- Strategic considerations.

For pipelines, companies recover the return on investment primarily through flow rates, so that a critical factor in making a decommissioning decision is the expected depletion rates of the producing area.

P&A

An operator must permanently plug and abandon (P&A) all unplugged and temporarily abandoned wells on a lease within 1 year after the lease terminates. If MMS determines that the well poses a hazard to safety or the environment or if the well is not useful for lease operations and not capable of profitable oil or gas production, the well may need to be P&A’d before this time.

Economic and strategic considerations determine if wells on a destroyed structure should be temporarily or permanently P&A’d. A temporarily abandoned well will be re-entered in the future when the field is redeveloped. If the decision is to cease production at the structure and not redevelop the field, all wellbores must be permanently P&Aed. In either case, prior to P&A operations, the operator must clear the debris around the site to establish access to the wellheads.

Well P&A procedures and tools are designed for vertical access, but hurricane-damaged wells may not allow vertical entry. Without the structure, the work requires a jack-up rig or a liftboat, and the operation may have similar characteristics and costs to plugging a wet (subsea) well.

Well conductors usually bend at the mudline with the toppled structure, and in some cases, the toppling may sever the conductors. To gain vertical access to the wellbores, the operation may require that the conductors be first cut before plugs are pumped into the well.

These operations are more expensive and risky than cutting conductors in the usual manner.

Removal options

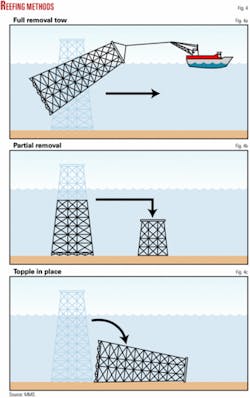

Federal regulations require platform removal from a lease within 1 year after production on the lease ceases. This is also the time when all remaining wellbores are plugged, and production tubing strings and conductors are cut and pulled in accordance with federal regulations. Under normal conditions, the operator has three options for removing the platform: complete removal, partial removal, or topple in place (Fig. 4):

In a complete removal, a lift vessel removes the jacket structure in one piece or in sections, depending on the jacket size and the vessel lift capacity. The work involves cutting off the foundation piles 5 m (15 ft) below the seabed and transporting the piles and removed jacket ashore for recycling, storage, refurbishment, or disposal. Another option is to transport the jacket and dispose of it at an artificial reef site.

In a partial removal, the work entails cutting off the jacket at a depth specified by US Coast Guard (USCG) regulations such that an unobstructed water column exists for safe navigation above the remaining part of the jacket. Abrasive cutting or divers are used to sever the jacket because explosives are not permitted in open water.

The bottom part of the jacket remains attached to the seafloor, while the top part may be taken ashore for recycling, storage, refurbishment, or disposal. Another option is to place the top portion on the seabed next to the bottom section of the jacket. The operator must satisfy all regulatory requirements for the creation of an artificial reef at the site.

A structure that is toppled-in-place involves cutting the jacket legs so that the jacket collapses under its own weight, or by using a pull barge to provide the forward momentum. Regulations require an unobstructed water column of a specific depth for a structure toppled-in-place and the structure must satisfy the regulatory requirements for the creation of an artificial reef at the site.

Site clearance

The last task in decommissioning is site clearance and verification. The operator has 60 days after removing the structure to clear the site and verify clearance.

For structures that are reefed in place, the regulators frequently waive site clearance and verification requirements. For structures destroyed in a hurricane, steel and other material debris may remain on the seabed in and around the site, depending on the nature of the removal operation and regulatory agency approval.

Destroyed structure removal

The risks involved in decommissioning destroyed infrastructure are higher than under normal conditions. Structures destroyed by storms cannot undergo the normal topsides inspection and preparation stage, such as flushing and cleaning piping and equipment, preparing modules and support frames, and flushing and cleaning pipelines.

A destroyed structure typically lies on the seabed similar to a structure toppled-in-place. In these cases, access to wells is more difficult, and the only thing holding back flow from the well is the subsurface safety valve.

If floating structures break free from their moorings, the structure may float away several miles from the field. For example, Hurricane Rita flipped the Typhoon tension-leg platform in Green Canyon-237 upside-down and moved it nearly 100 km from the field.

In June 2006, Typhoon was disposed of in a SARS in the Eugene Island area.

Liability

MMS regulations provide that a platform operator may be released from removal obligations if a state agency responsible for managing fisheries resources will accept liability. The Louisiana Fishing Enhancement Act established the Department of Wildlife and Fisheries as the responsible agency off Louisiana.

The state assumes ownership of the structure after a company donates it to the reef program and the state is responsible for any future costs of buoy construction and replacement, operation, and liability.

The Act absolves the donor and other participants constructing a reef from liability provided they meet the terms and conditions of the reef permit.

Donation requirements

Operators that donate a platform for an artificial reef can often lower the decommissioning cost below the cost of bringing the platform ashore for disposal, but many factors determine the cost of converting a platform into a reef, and subsequently, the cost savings, if any.5

Location is one of the primary factors. Structures close to shore that meet clearance requirements can be towed to the nearest port or scrap yard. Farther offshore, reefing is more economic when a structure is close to a designated reef planning area.

Different decommissioning options will generate various cost estimates based on the platform characteristics (size, weight, and complexity), site (water depth, distance to shore, and distance to nearest reef site), operator requirements (cutting method, scheduling, and contract structure), and conditions at the time of the operation (available equipment, market rates, and weather).

Cost savings from reefing can vary from less than 10% relative to the cheapest alternative to more than 100%, depending on the removal method, operator requirements, and assumptions involved in the estimate. In some cases, reefing may cost the operator more than removal to shore.

The state and operator obtain a third-party estimate of the cost for removal alternatives before the decommissioning operation. This estimate is the basis for determining the donation amount.

The operator and state split evenly the cost savings associated with a reef donation.

LARP statistics

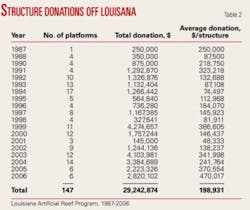

Table 2 shows the structures donated to LARP, donation amounts, and average annual donation per structure. From 1987-2006, operators have donated 147 structures at 36 sites and the trust fund has accrued $29.2 million plus about $5 million in interest, totaling $34.2 million.

The number and amount of donations vary with time, and during the past decade, operators have donated about eight structures/year at an average donation of $1.54 million/year, or $200,000/structure.

Eight of the 147 platforms donated to LARP through 2006 were destroyed by hurricanes, and 29 of the 147 structures are in SARS.

SARS definition

A site, and materials contained at the site qualifies as a SARS when one or more of the following criteria are met:

- There is a historical or biological significance associated with the site; if, for example, a particular area is a successful fishing spot frequented by fishermen or divers or if the site provides good fishery habitat.

- The site is part of a cooperative effort between the LARP and another state, federal government, or private group.

- The site contains shipwrecks or other derelicts that cannot be practicably removed or relocated, and the site provides benefits to the LARP.

- The site forms an integral part of experimental or demonstration projects undertaken by the LARP.

The accompanying box shows the procedures for establishing a SARS.

A site considered for SARS must meet the following criteria specified in Amendment II of the Louisiana Reef Plan:6

- Benefit recreational or commercial fishing, or fish habitat.

- Help fish populations by not removing existing material from site.

- Not a threat to navigation;

- Not currently in bottom trawlable area.

- Overall benefit user groups.

- Eliminate from an existing planning area an area of equal in size to the SARS.

- Except for possible trace amounts, the structures are free and clear of any hydrocarbons or other hazardous materials as listed in current US Environmental Protection Agency regulations.

Screening criteria

A Reef Priority Index (RPI) defines the priority of projects submitted for SARS review (see accompanying box).

The RPI provides a screening tool for the projects that then are evaluated on a case-by-case basis. Items taken into account include value of habitat formed, available fishing reports, number of platforms, ability of the site for disposing of additional structures, distance to nearby planning areas and other SARS sites, clearance, relief, pipelines, and proximity to mud-slide prone regions.

Locations without active pipelines were SARS candidates. Locations required a review if an active pipeline was within or bordering a lease at a distance less than 1,000 ft for the SARS.

Mud-slide prone areas in general are not appropriate reef sites because platforms may move, break, or become submerged. Submerged or buried platforms have little or no habitat value.

Another important factor in approving a SARS was the potential for disposing of additional structures at the site.

SARS

Before Hurricanes Katrina and Rita, LARP had 12 approved SARS that held structures destroyed in hurricanes, damaged in construction accidents, in biological studies, and met deepwater reef criteria (Table 3). The 12 SARS held 29 structures, including two drilling barges and one drilling rig.

Each SARS can accommodate 7-10 platforms, as shown in the development of West Delta-134, Main Pass-243, and Eugene Island-313.

At EI-273, EI-309, EI-322, EI-324, EI-384, SP-89, and VE-395, only one or two structures are currently contained at each SARS, but the sites will likely attract additional structures in the future.

Following Hurricanes Katrina and Rita, the LARP advisory council reviewed the scope of the damage from the storms and discussed the expected effect on the program. The council made recommendations to approve, to approve with modification, to discuss for future planning purposes, and to reject.

Project modifications typically require platform additions or removals at the site, and the discussion for planning purposes normally centered on the site’s suitability for future additions and deepwater sites for large platforms.

In June 2006, the council reviewed applicant data for 25 projects with 39 destroyed platforms. Of these, the council approved 7 projects with 21 platforms for SARS (Table 4, Fig. 2).

In November 2006, the council reviewed 13 projects with 25 platforms and 3 mobile offshore drilling units (MODUs). The projects were both new and previously reviewed-reconfigured projects. The council approved 3 projects with 14 platforms (Table 4, Fig. 2), and did not recommend any of the MODU projects.

At yearend 2006, the council had approved 10 projects with 35 platforms for SARS. The average RPI for the approved SARS projects was 24.7 while for the 27 rejected projects it was 6.5.

Notable projects

Two SARS projects are of particular interest. An eight-pile platform owned by Taylor in MC-20 failed in a mud-slide region and was nearly 75% submerged below the mud line. Estimates indicate that the dredging for access and lifting the structure would require removal of mud equal to the volume of the New Orleans Superdome. The council did not approve the structure for a SARS because the habitat value of the Taylor platform is considered minimal.

BP proposed a reef site for an eight-pile platform at GI-40/48, less than 3 miles from the Louisiana Offshore Operating Port (LOOP) anchorage area. Clearance restrictions will require lighted buoys at the site, and because of the proximity to LOOP, the BP project will require further evaluation and risk assessment prior to approval.

References

- Dauterive, L., Rigs-to-reefs, policy, progress, and perspective, MMS 2000-073. US Department of the Interior, MMS OCS Region, New Orleans, 2001.

- Reggio, V.C. Jr, Rigs-to-reefs: the use of obsolete petroleum structures as artificial reefs, OCS Report/MMS 87-0015, MMS Gulf of Mexico OCS Regional Office, Metairie, La., 1987.

- Wilson, C.A., and Van Sickle, V.R, “Louisiana state artificial reef plan,” Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries, Technical Bulletin, Vol. 41, 1987, pp. 1-51.

- “Oil and Gas and Sulphur Operations in the Outer Continental Shelf -Decommissioning Activities; Final Rule May 17, 2002,” Federal Register, Vol. 67, No. 96, pp. 35398-412.

- Kaiser, M.J., “The Louisiana artificial reef program,” Marine Policy, Vol. 30, 2006, pp. 605-23.

- Amendment II to Louisiana’s Artificial Reef Plan, Special Artificial Reef Sites, Adopted at the Council Meeting, Baton Rouge, La., Apr. 8, 2003.

The authors

Mark J. Kaiser ([email protected]) is research professor and director, research and development at the Center for Energy Studies at Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge. His primary research interests are related to policy issues, modeling, and econometric studies in the energy industry. Before joining LSU in 2001, he held appointments at Auburn University, the American University of Armenia, and Wichita State University. He has a PhD in industrial engineering and operations research from Purdue University.

Rick Kasprzak ([email protected]) is the program manager of the Louisiana Artificial Reef Program for the Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries. He previously was a biologist with the Department of Wildlife and Fisheries focusing on the population dynamics of finfish and shrimp populations. Kasprzak has a BS degree from Loyola College, Maryland.

SARS procedural guidelines

Establishing a SARS follows a well-defined set of procedures, as follows:

- The Louisiana Artificial Reef Coordinator will draft a proposal to establish a SARS for submission to the Artificial Reef Council. The proposal shall include location, clearance, bottom profile, condition of structure, list of potential hazardous material, and justification that the criteria outlined are met.

- Following acceptance of the proposal by the Louisiana Artificial Reef Council, the intent to create a SARS will be announced through a Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries news release.

- Thirty days following news releases, if no major objections are received, the Louisiana Artificial Reef Coordinator will apply for the necessary permits. In the event objections are received, a public hearing will be held to provide further information before a final determination by the Council.

If appropriate, a Deed of Donation will be agreed upon by the donor and recipients of the reef material.

The Secretary of the Department of Wildlife and Fisheries shall sign all necessary permits and the Deed of Donation.