Since the early 1990s China’s skyrocketing demand for energy has dramatically affected global markets and international policy. To close the growing gap between stagnant domestic production and expanding consumption, Beijing has sought to reform its energy sector and diversify its energy mix and sources. Improvements are still needed in Chinese energy governance, however, to enhance energy conservation and diversify the energy mix.

Furthermore, Beijing’s aggressive pursuit of energy security on the international scene has become a global concern. Securing supplies from abroad has become a major component of the country’s foreign policy.

Swift economic growth

Following the establishment of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in 1949, the nation was largely self-sufficient in energy. The largest oil field, Daqing, was discovered in 1959 and largely met China’s petroleum demand. Thus, the first two “oil shocks” (1973-74 and 1979-80) had little impact on the Chinese economy and energy sector. Indeed, China exported crude oil to several of its Asian neighbors during this period.

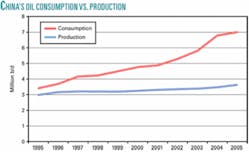

Since the early 1980s, however, China’s economy has grown impressively. This growth, in conjunction with a population of more than a billion people, demanded more energy than domestic production could provide. In 1993 China became a net importer of oil, and by 2006 it was the world’s third-largest net importer of oil behind the US and Japan.

This gap between stagnant energy production and fast-growing consumption is projected to expand even further in the next 2 decades. According to the Energy Information Administration (EIA), China’s oil consumption is projected to rise to 15 million b/d by 2030 from 5.6 million b/d in 2003 (a 3.8% average annual change-the highest in the world). Similarly, natural gas consumption will jump during the same period to 7 tcf from 1.2 tcf (a 6.8% average annual change-again the highest in the world).

China’s limited oil and gas reserves further complicate its energy outlook. In 2006 proved oil reserves were 16 billion bbl (1.3% of the world’s total), and gas reserves were 83 tcf (also 1.3% of the world’s total).

This combination of limited indigenous energy resources and rising demand has prompted Chinese leaders to adopt a multifaceted energy strategy. Three elements of this strategy can be identified:

- Reforming the energy sector to maximize domestic production and attract foreign investment.

- Diversifying the energy mix to reduce the nation’s dependency on fossil fuels and contain pollution.

- Diversifying energy sources to restrain dependence on one or a few producing regions.

Energy sector reform

Chinese leaders agree that a viable and aggressive energy policy is essential to maintain and further expand the high economic growth of the last 2 decades. However, unlike many other countries, China lacks a national energy agency to draw and implement such a policy. Several national agencies have been established and dissolved since the PRC’s founding.

The Ministry of Fuel Industries was abolished in 1955, when separate ministries for coal, electricity, and oil were established. In 1970 a new Ministry of Fuel and Chemical Industries combined the functions of those three ministries, but it was dissolved 5 years later.

In 1988 a Ministry of Energy was launched to oversee coal, oil, nuclear, and hydroelectric development, but it was dissolved in 1993.1 In the early 2000s the central government created the Energy Bureau under the National Development and Reform Commission as an integrated central authority responsible for developing long-term energy strategies.2 In June 2005 this bureau was replaced by the Energy Leading Group, a cabinet minister organization chaired by the prime minister. The purpose of this new agency is to strengthen energy policy planning and implementation.3 These continuing changes suggest that China lacks a strong national mechanism to oversee its energy sector.

Institutional instability aside, oil and gas resources are controlled by three state firms: China National Petroleum Corp. (CNPC), China Petroleum & Chemical Corp. (Sinopec), and China National Offshore Oil Corp. (CNOOC). The Chinese government maintains a majority stake in all of them. CNPC and Sinopec operate almost all of China’s refineries and the domestic pipeline network, while CNOOC has the most expertise with international transactions.

The country’s first private sector company, the Great Wall Petroleum Group, was founded in 2005.

These corporations seek to enhance China’s energy security by investing in domestic exploration and development and securing foreign supplies. In addition, Beijing seeks to neutralize threats to oil and gas shipments and to build a strategic petroleum reserve (SPR). The idea of building an SPR has been considered since the late 1990s, and a proposal to build one was approved in the tenth 5-year plan (2000-05). Several important issues such as the amount of oil to be stored and the time to start the reserve have been under intense debate. Chinese officials assert that eventually the SPR will hold oil covering about 90 days’ supply.

Energy diversification

China’s energy consumption is dominated by fossil fuels, particularly coal. This energy mix has caused serious pollution and threatens the sustainable energy supply. Indeed, many of China’s cities are among the most polluted in the world.

Production from Daqing oil field peaked in the 1970s, and has fallen since 2004. Chinese authorities have sought assistance from international oil companies to boost oil recovery and extend the life of producing fields. Furthermore, heavy investments have been made in exploration and development, particularly offshore.

In the mid-2000s Daqing, Shengli, Liaohe, Xinjiang, Changqing, Sinopec Star, and Zhongyuan fields provided most of China’s oil production. Since the early 1990s domestic production has failed to keep up with demand.

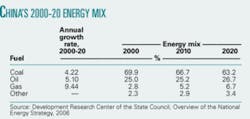

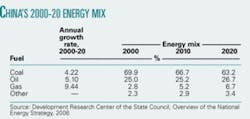

Figures in the table show two important trends:

- Natural gas represents a small proportion of China’s energy mix.

- Gas consumption is growing faster than that of coal and oil. Several discoveries have been made in recent years, including Puguang, Sulige, and Kela-2 gas fields.

Most of China’s gas fields are in the western and north-central areas away from the population and industrial centers in the east and southeast. To offset this imbalance, the Chinese government built the West-East gas pipeline.

Other pipelines from Kazakhstan and Russia are under consideration. In addition, two LNG import terminals, one in Guangdong and the other in Fujian, have been built, and several others have been proposed. China’s gas development is still in its infancy, hence it has great potential.

Future consumption will draw on three sources: higher domestic gas production, emerging LNG import terminals, and proposed international pipeline projects.

While China is the world’s largest producer and consumer of coal-its primary energy source-its dependence on the substance is projected to decline slightly.

In recent years, Chinese authorities have sought foreign investment to expand coal liquefaction projects. The goal is to reduce dependence on oil and to increase energy efficiency and environmental benefits.

Chinese authorities also have shown strong interest in other sources of energy, particularly renewables and nuclear power.

In January 2006 the Renewable Energy Law took effect. It establishes a regulatory framework for renewable energy development and provides economic incentives and financial support for research and development. Similarly, China has stepped up the pace of nuclear power plant construction and has one of the most ambitious plans for nuclear power in the world.

Source diversification

Securing future energy supplies has become a key aim of China’s energy and foreign policies. Beijing officially joined the World Trade Organization in December 2001. Around this time, then-Premier Zhu Rongji, and Hu Jintao, general secretary of the Communist Party, called on Chinese companies to pursue a Zou Chu Qu or “going-out” policy, which should be seen as part of a broader policy of global economic engagement.4

Three major characteristics of this policy can be identified:

- Chinese oil companies have only a short history of mergers and acquisitions abroad. The policy was launched and gained momentum only in the last several years. In the mid-1990s most of China’s oil deals were in three countries-Indonesia, Oman, and Yemen. A decade later Chinese companies are actively pursuing oil deals in North and South America, Africa, Asia, and the Middle East.

- Chinese companies have sought to establish presence mostly in countries where American and European companies are absent or have withdrawn. These targeted countries, such as Iran, Sudan, Uzbekistan, and Venezuela, have adopted domestic and foreign policies that are largely in contrast with the interests of Western powers.

- Despite conscious efforts to diversify import sources, China’s oil suppliers are heavily concentrated in the Middle East and Africa. These regions are likely to continue providing the bulk of China’s oil needs.

Following are profiles of countries and regions in which China has shown special interest:

Russia

On the bilateral level, China’s relations with Russia have substantially improved since the early 1990s. Close cooperation between the nations was enshrined in the Friendship and Cooperation Treaty of July 2001.

Since June 2005, Russia and China signed the final demarcation of their long borders. Bilateral trade has experienced exponential growth. China has become Russia’s second-largest trading partner after the European Union.

Despite similar perceptions and joint interests, some Russian policy-makers are concerned about China’s rising economic and strategic power. In addition, Russia’s Pacific provinces are vulnerable to China’s legal and illegal immigration. Finally, Beijing’s and Moscow’s interests differ in Central Asia, where both seek influence.

These contradictory strategic trends have restrained energy cooperation between China and Russia. In 2006 CNPC wanted to buy $3 billion of the shares in the Russian energy giant Rosneft, but it was allocated a bloc of shares valued at $500 million.

However construction has begun on parts of the long oil pipeline Russia is laying between Taishet in Eastern Siberia to Skovorodino on the border with China.

Central Asia

Central Asia is particularly attractive to China for many reasons: The region is known to have large hydrocarbon reserves; imports from Central Asia would reduce China’s overwhelming dependence on the Middle East; and shipping oil and gas by land from Central Asia would help China avoid sea lanes largely dominated by the US navy.

Central Asian producers, for their part, can reduce their equally overwhelming dependence on Russia by exporting some of their oil and gas to China.

Within this context, China and Central Asian producers have pursued their mutually beneficial energy interests. In April 2006 Chinese President Hu Jintao signed agreements with the late Turkmen President Saparmurat Niyazov for Turkmenistan to sell gas to China and to build a pipeline to deliver it. In June 1997 CNPC purchased 60% of Kazakhstan’s Aktyubinsk Oil Co. for $4.3 billion. In October 2005 CNPC finalized the purchase of Petrokazakhstan, whose assets include 11 oil fields and licenses to seven exploration blocks.

In May 2006 China began receiving crude oil from its first transnational oil pipeline. The pipeline was developed by the Sino-Kazakh Pipeline Co., a 50-50 joint venture of CNPC and Kazakhstan’s KazTransOil. The Kazakh and Chinese governments also have explored the possibility of laying a gas pipeline parallel to the oil pipeline.5

Africa

The Chinese role in Africa has dramatically changed in the last half-century. In the 1960s and 1970s Beijing’s interest centered on repelling Western imperialism and on building ideological solidarity with other underdeveloped nations to advance Chinese-style communism. Following the Cold War, Chinese interests evolved into more pragmatic pursuits such as trade, investment, and energy.

Unlike their Western counterparts, Chinese leaders avoid controversial political issues such as human rights, promoting democracy, and proliferation of weapons of mass destruction. Instead, China’s approach towards Africa is almost exclusively based on and driven by commercial interests.

In November 2006 Chinese and African leaders adopted an action plan in which the two sides “resolved” to bolster joint energy and resources exploration and exploitation under the principle of reciprocity and common development. The document noted that China and Africa are “highly complementary” in energy and resources and that better information-sharing and pragmatic cooperation in these sectors serve the long-term interests of both sides. Beijing confirmed its intention to help African countries turn their advantages in energy and resources into development strengths.

In the last several years Africa has become a major oil supplier to China. In the mid-2000s Africa supplies almost a third of China’s oil imports. Most of this oil comes from Angola and Sudan. In 2006 Angola overtook Saudi Arabia as China’s single largest oil supplier.

The Middle East

Like African states, Middle Eastern oil producers share significant commercial and strategic interests with China. With oil, Middle Eastern producers want to secure a buyer, and China wants to secure a reliable supplier.

For the last several years China has taken an assertive role in developing Iran’s hydrocarbon resources. In October 2004 Sinopec signed a memorandum of understanding to buy 250 tonnes of LNG from Iran over the next 25 years in exchange for the development of Iran’s Yadavaran oil field. This agreement, estimated at $70-100 billion, would offer Sinopec a 51% stake in Yadavaran and deliver 150,000 b/d of Iranian crude oil to China in the same time period.

In June 1997 a consortium of Chinese energy companies signed a 22-year production-sharing agreement with Saddam Hussein’s regime to develop Iraq’s oil fields after the lifting of UN sanctions. In the post-Hussein period, the status of this agreement remains uncertain.

Relations between Beijing and Riyadh have improved in recent years. Visits by top officials from both countries illustrate this close and growing partnership. In 1999, then-President Jiang Zemin visited Saudi Arabia and signed several trade and energy agreements.

Since then the kingdom has become a major oil supplier to China. After long and unsuccessful negotiations with American oil companies to develop Saudi Arabia’s gas, Riyadh awarded concessions to European, Russian, and Chinese companies in 2004.

On the other hand, China has attracted Saudi investment in joint ventures to expand and upgrade Chinese refining capacity. In January 2006 King Abdullah visited China on his first trip outside the Middle East since becoming the Saudi ruler. This was the first visit by a Saudi king to China since the two countries established diplomatic relations in 1990. Four months later, President Hu Jintao made his first state visit to Saudi Arabia.

References

- Daojiong, Zha, “China’s Energy Security: Domestic and International Issues,” Survival, Vol. 48, No.1, Spring 2006, pp. 179-90.

- Yi-Chong, Xu, “China’s Energy Security,” Australian Journal of International Affairs, Vol. 60, No. 2, June 2006, pp. 265-86.

- Goldstein, Lyle, Kozyrev, Vitaly, “China, Japan, and the Scramble for Siberia,” Survival, Vol. 48, No.1, Spring 2006, pp. 163-78.

- Leverett, Flynt, Bader, Jeffrey, “Managing China-US Energy Competition in the Middle East,” Washington Quarterly, Vol. 29, No.1, Winter 2005-06, pp. 187-201.

- Neff, Andrew, “China Competing with Russia for Central Asian Investments,” (OGJ, Mar. 6, 2006, p. 41).

The author

Gawdat G. Bahgat is professor of political science and director of the Center for Middle Eastern Studies at Indiana University of Pennsylvania in Indiana, Pa. He has taught at the university for the past 11 years and has held his current position since 1997. He also has taught political science and Middle East studies at American University in Cairo, the University of North Florida in Jacksonville, and Florida State University in Tallahassee. Bahgat has written and published six books and monographs on politics in the Persian Gulf and Caspian Sea and has written more than 100 articles and book reviews on security, the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction, terrorism, energy, ethnic and religious conflicts, Islamic revival, and American foreign policy. His professional areas of expertise encompass the Middle East, Persian Gulf, Russia, China, Central Asia, and the Caucasus. His latest book is “Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons in the Middle East (2007).” Bahgat earned his PhD in political science at Florida State University in 1991 and holds an MA in Middle Eastern studies from American University in Cairo (1985) and a BA in political science at Cairo University (1977).