LNG TRADE-1: US gas supply security requires source diversity

The necessary expansion and diversification of US natural gas supply sources brings with it increased exposure to political and economic risks that could cause this supply to be interrupted.

Part 1 of this article, presented here, examines the nature of US demand, the growing role of LNG in meeting this demand, and how insufficient diversification of supply sources would expose the country to particularly acute supply risk. Part 2 will address other issues complicating natural gas supply to the US as well as examine Europe’s dependence on Russian gas.

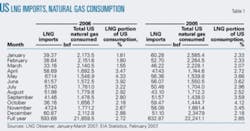

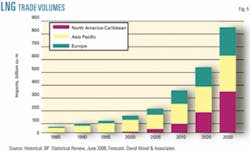

The US imported 16.81 billion cu m (594 bcf) of LNG in 2006, some 2.72% of the 619 billion cu m (21.86 tcf) of natural gas it consumed (Table 1). This compared with 2005 US imports of 17.92 billion cu m (633 bcf) of LNG, some 2.85% of the 630 billion cu m (22.24 tcf) of gas it consumed.

High US gas prices, slightly higher domestic gas production, and higher LNG prices in Europe, which led to some LNG cargoes being diverted from the US, caused the slight contraction in LNG imports and drop in US gas consumption. Imported LNG, however, continues to provide a pivotal incremental source of natural gas supply in tight winter market conditions, moderating the magnitude of any potential price spikes.

Global LNG industry construction in 2007 and 2008 will lead to 50 million tonnes/year of new liquefaction capacity, 14 million cu m of new LNG shipping capacity (some 90 vessels), and nearly 90 million tonnes/year of regasification capacity. The US, however, continues to lag in its efforts to add new LNG import capacity.

Lack of infrastructure to land sufficient LNG through 2007 and 2008, due to slow permitting (2003 and 2005) and persistent obstructive regional governments in the areas where supply is most needed (New England and California) is likely to cause gas-supply shortages, particularly if winter weather is severe and demand growth is sustained. The natural gas industry (both North American and international companies) has proposed more than 50 projects to build North American LNG import and regasification terminals.

The US produced 50.66 bcfd of natural gas in 2006, up from 49.59 bcfd in 2005. Russia produced 57.9 bcfd of gas in 2005.

Reserves-production ratios, however, show that US natural gas production represented 9.6% of its proven reserves and 81.4% of its annual gas consumption in 2005, requiring substantial imports to fill the gap. By contrast, Russian production represented 1.25% of its proven reserves and 147.7% of its annual gas consumption in 2005, leaving substantial volumes available for export.

The long-term implications of this imbalance for the US (and several other OECD countries) require prompt action. Delays in building new LNG receiving terminals and failure to further diversify gas procurement, in terms of both geographic sources of supply and the corporations operating the LNG supply chains, are likely to lead to serious natural gas supply interruptions and price hikes for gas consumers before 2020 and will be even more difficult to remedy then than now.

Permitting, opposition

The US government has slowly but progressively acted to streamline the permitting process for LNG terminals since 2002, primarily through the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission and the US Coast Guard.

FERC eliminated open-season requirements in 2002, giving developers clearer incentive to invest in LNG terminals, and progressively asserted its authority in determining facility siting. FERC ruled in December 2002 that the proposed Hackberry (La.) LNG import terminal could be built without complying with the open-access requirements that had been strictly applied to all parts of the gas transmission chain previously as part of ensuring open competition in the deregulated gas market.

The Hackberry decision has encouraged proposals to build new receiving terminals by removing the risk that potential developers might lose some of their built capacity by having to offer it to third-parties at market rates.

Moves in September 2004 sought to make FERC a one-stop LNG facilities regulator, eliminating conflicts with other agencies (e.g., military and state authorities) that had previously caused delays.

The Energy Policy Act of 2005 and new FERC regulations to implement both the act and maritime safety and security processes recommended by the Coast Guard, cleared away many potential obstacles and delays impeding approval of, and investment in, LNG terminals. But they also require project developers to engage in a minimum 6-month prefiling process and conduct more detailed waterway safety and security assessments earlier in project development than was previously the case.

Navigation and Vessel Inspection Circular (NVIC) 05-05, also issued in 2005, further affects the approval process for new terminals. Together with FERC’s filing process, NVIC requirements extend the full approval process to between 18 months and 2 years. In some locations, even once all federal hurdles have been crossed, state legal challenges can still delay a project’s progress into the construction phase.

Under construction

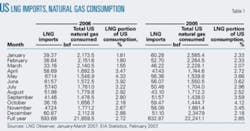

In late 2006 only nine new onshore terminal projects were under construction in North America, including two projects each in Canada and Mexico (Table 2). Several other projects have been permitted. The five under construction in the US are along the Gulf Coast.

Total peak sendout gas capacity of the nine projects is 14 bcfd (5 tcf/year). But such plants usually average throughput of less than 60% of maximum capacity, limiting their likely contribution to 3 tcf/year when they become fully operational in 2008-09.

These projects will help the US diversify its fuel supply by tapping global LNG markets. Expanding LNG import capacity is a necessary and, by many, an accepted step for the US to take.

Utilities contracting their gas supply from remote foreign LNG suppliers, however, face a range of new risks to manage and, where possible, mitigate. These geopolitical risks make the US gas and power utilities and their end users more vulnerable to potential supply interruptions and price spikes, in a future dependent on long-distance LNG supply chains from several continents.

The new Altamira LNG receiving terminal in northeast Mexico (Shell 50%, Total 25%, Mitsui 25%) became fully operational in late 2006, with an initial gas sendout capacity of 500 MMcfd, and potential to expand that to 700 MMcfd. The plant consists of two 150,000-cu m full-containment LNG storage tanks that can handle marine tankers with cargoes up to 200,000 cu m.

The LNG imported, however, is contracted to Mexican utility Comisión Federal de Electricidad (CFE) at 185 bcf/year, and no plans exist to import additional LNG for re-export to US.

Although this, and some of the Mexican terminals planned for the country’s west coast, will improve North America’s overall natural gas balances by serving growing natural gas demand in Mexico and filling its supply gap, it will not solve the US gas shortfall. It is clear that the most vulnerable regions of the US gas market, namely California and New England, need to build their own infrastructure. Imported LNG can help balance North American gas supply, but for the US to improve its own security of supply it must commit to build LNG receiving terminals in strategic areas within the US.

New England

Gas-fired generation accounted for about 16% of New England’s total electric consumption in 1999; this has since risen to closer to 40%, according to ISO New England (the entity responsible for managing the region’s gas transmission system), and could reach 50% by 2010.

Consumption of natural gas in the New England market has grown at one of the fastest rates in the US over the past 10 years. Natural gas is now the leading source of fuel for electric generation in New England. New England’s monthly load factor for gas pipelines approached 90% over the 3 mid-winter months this year, indicating little redundant capacity on gas pipelines during peak periods. If New England’s economy is to grow at the 1%/year forecast by the Energy Information Administration, much of that growth will be driven by increased power and therefore gas consumption, placing more pressure on an already strained gas supply network.

New England is at the end of the pipeline systems originating in the US Gulf Coast and from northeastern and western Canada. New England is more dependent on Canadian gas imports (40% of supply) than other US regions (~15%). LNG imports through Suez Energy NA’s Everett terminal in Boston make only 15% of New England’s gas supply.

Because the region lacks any gas storage, however, regasified LNG makes up 25% of the gas delivered on a peak winter day. Its tight supply situation, lack of underground gas storage, and limited existing LNG infrastructure cause the New England gas market to experience significantly higher wholesale and residential natural gas prices than the rest of the US.

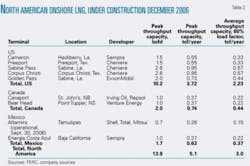

Fig. 1 shows the location of proposed LNG receiving terminals in Canada and the Northeast US. Canaport terminal is set for completion in late 2008, having started construction in May 2006. RepsolYPF has taken a 75% stake in the facility (Irving Oil, 25%) and 100% of the capacity (1-bcfd sendout capacity from two 160,000-cu m tanks).

Anadarko sold its Bear Head facility in July 2006, having started and halted construction earlier in the year when it failed to secure an LNG supply deal. Venture Energy bought Bear Head for $110 million, but still has to build the facility and find a supply deal.

MapleLNG Ltd’s proposed site at Goldboro, NS, adjacent to the Maritimes and Northeast Pipeline (M&NP) intake station, received environmental approval in March 2007. 4Gas North America and Suntera Canada Ltd., joint-venture partners in MapleLNG, purchased the LNG portion of an integrated LNG-petrochemical complex from Keltic Petrochemicals Inc. in March 2006 but have yet to announce an LNG supply deal.

MN&P will require five new compressor stations to accommodate additional capacity, and a new 145-km pipeline is planned from the Canaport site to the US border to tie into the US part of the MN&P network.

Other plants proposed in Canada have yet to make substantial progress.

Of the projects in the Northeast US, BP’s Crown Landing, NJ, and Hess-Poten & Partners Weaver’s Cove Energy, Fall River, Mass., terminals have received permitting but have yet to commence construction.

Public opposition and legal challenges continue to delay these and other New England LNG receiving terminal projects.

End users

The US imports 25% of the natural gas it consumes, mainly from Canada. LNG imports will play an increasingly central role in meeting US needs as demand grows, and Canada’s ability to supply declines. Natural gas provides 15% of US electricity generation; 45% of residential heating fuel; and 30% of the energy and petrochemicals consumed by agriculture and industry. Gas also supplies minor volumes of feedstock for the manufacture of hydrogen, a promising new entrant in the development of alternative fuels.

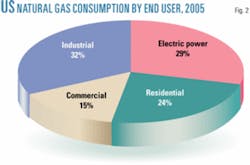

Fig. 2 shows the average consumption of natural gas by end user in the US during 2005. Industrial, electric power generation, and residential heating dominate natural gas consumption in US.

Geopolitical risks

Rapid depletion of US domestic gas reserves inexorably leads to growing dependence on foreign imports from beyond the politically safe confines of Canada. The future LNG supply mix for the US is likely to come from Algeria, Angola, Egypt, Equatorial Guinea, Libya, Nigeria, Norway, Peru, Russia, Qatar, Trinidad, and Yemen.

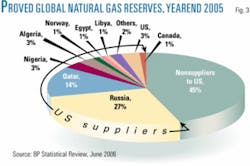

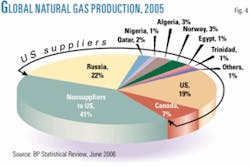

These countries (including the US itself and Canada) hold some 55% of global gas reserves (Fig. 3) and 59% of global production (Fig. 4). Diversity of supply from large and smaller reserve-holding countries is critical, as several of these countries have large radical minorities, which if they gained power would attempt to disrupt LNG supplies to OECD countries.

If political events interrupted the supply from just a few of these countries, the remainder might struggle to sustain global gas demand for long. A number of political scenarios could easily lead to such an outcome.

Risk exposure

Expanding US dependence on imported LNG will expose utilities and their customers to a spectrum of risks including political instability, fiscal delinquency, terrorism, war, and the prospect of market manipulation by a prospective international gas cartel. LNG undoubtedly increases US dependence on overseas energy producers, particularly in the Middle East, where much of the reserves are located. This increased dependence makes many in the US uncomfortable.

Even Trinidad & Tobago-the source of most LNG imported by the US in recent years-shows signs of a government keen to increase the power it wields over the LNG produced in its territory.

Geopolitically driven supply interruptions seem inevitable at some stage during the next decade or so. Unless LNG supplies are broadly diversified, these geopolitical risks may increase US gas and power utilities’ vulnerability in the long-term to the price shocks LNG imports are striving to avert.

OECD countries such as Japan, Germany, France, and South Korea, however, have depended on imported gas for decades and have succeeded in establishing and managing long-term relationships with a range of suppliers. The US-and such new entrants into the LNG import sector as the UK, India, and China-can learn many lessons from such longstanding relationships.

Gas demand is set to increase substantially over the next 2 decades in all consuming regions (Fig. 5), even as geopolitical tensions impacting gas supply chains intensify.

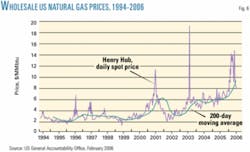

Embracing long-term high volume LNG supply contracts linked to stable pricing formulas should provide long-term confidence that LNG sale terms are sustainable for both buyer and seller on a commercial basis. Such price formulas in the US could involve a range of competing power-generation fuel and electricity prices, as well as short-term Henry Hub gas prices, reducing the potential effect of LNG supply interruptions caused by price volatility and gas price spikes that have characterized deregulated markets such as the US in recent years (Fig. 6).

Bibliography

BP Statistical Review, June 2006.

International Energy Agency, World Energy Outlook, 2006.

“LNG Import Statistics, 2006,” LNG Observer January-March 2007, p.25.

US Energy Information Administration, Natural Gas Monthly, February 2007.

US Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, Office of Energy Projects, “Existing and Proposed North American LNG Terminals, Map 16,” February 2007.

US Government Accountability Office, “Natural Gas: Factors Affecting Prices and Potential Impacts on Consumers,” statement of Jim Wells, GAO director, natural resources and environment, Feb. 13, 2006.

The author

David Wood ([email protected]) is an international energy consultant specializing in the integration of technical, economic, risk, and strategic information to aid portfolio evaluation and management decisions. He holds a PhD from Imperial College, London. His work focuses on research and training across a wide range of energy related topics, including project contracts, economics, gas-LNG-GTL, and portfolio and risk analysis.