Chinese downstream development depends on GDP growth

China, a key country in the worldwide downstream petroleum industry, has had the largest influence on global refined product demand growth. The influence of China on Asian and global refined product markets has grown proportionately to its economy and will continue to do so in the near future.

China Petroleum & Chemical Corp. (Sinopec), China National Petroleum Corp. (CPNC), and China National Offshore Oil Corp. (CNOOC) have been cutting deals to access energy resources around the world. The companies have also actively been expanding refining capacity, a trend that will continue in the long term.

China’s overall challenge is to sustain its economic growth and relieve the pressures that accompany this expansion. High on the list of pressures is for Chinese refiners to maintain the supply of key refined products.

The Chinese government will attempt to contain the demand for refined products, but it is more likely that there will be more pressure to expand the economy; this will create a greater potential for increased demand in the various Chinese refined product forecasts. China’s needs will be such that alliances and participations with foreign firms that were resisted historically may be more achievable and profitable in the future.

Economy

China’s economic growth is a part of an overall plan by the Chinese government. The Chinese government understands that sustaining the government’s legitimacy depends in part on delivering, to the population at large, a satisfactory GDP per capita measured by international benchmarks.

For the long term, the Chinese government’s goal is to provide a GDP per capita to the Chinese people that is similar to that enjoyed by OECD nations-Europe, the US, Japan, Korea.

That GDP per capita goal carries with it the expectation of all the accoutrements of wealth-larger homes, travel, automobiles, and modern energy-consuming appliances. This achievement would take decades; in the meantime one can expect policies geared toward a broader based, consumer-oriented economy.

The implications of a nation as large as China achieving such an economic goal are significant. The population of China is greater than that of all OECD nations combined.

With a population as large as China’s, coming even close to OECD-level GDP per capita implies a huge draw on world resources. If these goals were met, or even approached, world crude oil demand would increase dramatically.

China’s long-term goals are not unprecedented. A useful point of reference is the economic experience of Japan.

Japan averaged about 7.5%/year real GDP growth during 1950-80. That period saw Japan’s GDP per capita increase from about 15% of the US level to about 85%. China seeks perhaps to parallel that level of performance, albeit with a far larger population.

China’s economy should continue to experience strong growth for the short-to-medium term. The country must overcome some fundamental issues such as a shortage of power and basic raw materials; however, China has been resourceful in marshalling its resources to solve problems quickly.

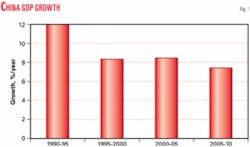

Although China seeks to protect its economy from unsustainable growth patterns that would trigger damaging volatility, the overall outlook is quite positive. And although China’s current efforts are aimed more at cooling the economy, its GDP growth will average about 7.5%/year during 2004-10 (Fig. 1), a rate that in principle can be sustained for many years.

Petroleum

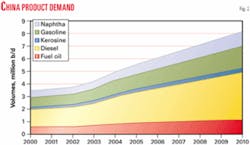

China’s demand for refined products will continue to grow (Fig. 2).

Gasoline is important to China because the country is modeling much of its economy on the US. The central position of the automobile in US culture is apparent to China and car ownership is expanding rapidly there.

China is taking many steps to encourage automobile ownership. Bicycles are banned from major streets in large cities. Automobile manufacturing plants are expanding rapidly, usually in joint ventures with leading foreign automakers. Gasoline taxes are low, similar to US levels.

In 2004, China took steps to curtail automobile purchases by constraining credit; but those are only temporary measures and part of a short-term program to cool the economy from excessive growth rates.

Automobile ownership is quite low in China. The Chinese private automobile fleet consists of about 20 vehicles/1,000 people, as compared with 120 for Thailand and 600 for more-advanced European Union countries. There is tremendous upward potential for the automobile industry in China.

Automobile ownership levels will most probably increase substantially in the near-to-medium term. Credit-tightening moves that the Chinese government imposed this year discouraging rapid automobile ownership growth are only temporary and will probably be loosened in the near future.

For the wealthier parts of China such as the coastal provinces, rates of automobile ownership similar to or greater than Thailand are possible.

Gasoline demand per automobile in China is relatively low. Although the number of automobiles is growing rapidly, many new vehicles see relatively light use by Western standards.

Demand for gasoline will still grow at relatively modest levels during the next 5 years. Beyond then, there is greater potential for growth in the per-capita private automobile ownership and shifts in private-automobile use patterns could translate into far greater gasoline demand.

Diesel demand in China has risen principally in the transport sector. As in the US, diesel is used as a heavy vehicle fuel far more than as an automobile fuel.

Recent increases in diesel demand, however, are related in part to a power shortfall in China. The country suffers from persistent power shortfalls particularly in the summer months. These shortfalls are concentrated in the coastal regions that are experiencing the greatest economic growth.

Power demand growth is partially a result of the rapid growth of electricity-consuming appliances such as air-conditioning units. The power shortfalls trigger rolling blackouts in some regions. Many industrial and major commercial power companies respond to power shortfalls by installing back-up power supplies, usually diesel-driven generator sets.

The power sector has therefore contributed to recent diesel demand increases, which should continue for the next few years. China is developing many new coal, gas, nuclear, and hydro powered electrical-generating stations that should mitigate the power-shortage problem in the medium term and perhaps decrease the demand for diesel for power production.

Chinese fuel oil demand is also growing. Fuel oil is used as a substitute for coal for industrial heating purposes. Chinese fuel oil production is quite low.

The typical Chinese refinery is medium sized but highly complex; coking and resid FCC units are common. China’s refineries, therefore, produce less than 10% fuel oil on average, a percentage that has been decreasing.

Just as automobile penetration per capita is low in China, so is petrochemical penetration. China has tremendous growth potential and there are numerous new projects to build plants that will manufacture olefin-based and aromatic materials.

Unlike many countries in Asia, China also consumes gas oils as petrochemical feeds, which provides an element of flexibility that is lacking elsewhere. Ethane and LPG feedstocks are not widely used because China’s energy consumption has focused on feedstocks other than gas.

Evolution of the gas system may create an economic opportunity for ethane extraction. Nevertheless, China will require about 540,000 b/d more naphtha in 2010 than in 2004; this demand must be met with a combination of indigenous refining and rapidly growing imports.

Refining

A big question is whether China’s refining sector can provide all the country’s petroleum products. During the past 2 years, China’s petroleum demand grew so rapidly that state planners and national oil companies were taken by surprise.

Refining capacity additions by Sinopec and CNPC have lagged demand, which has led to a short-term opportunity for imports and for “social refiners” in China to make up the difference. (More about “social refiners” presently.)

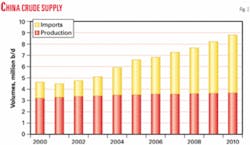

China’s crude consumption has risen very rapidly and strained capacity (Fig. 3). After several years of modest growth, product demand and processing rose rapidly in 2004.

Most of the growth in crude supply is from international sources. Domestic upstream growth consisted mainly of crudes that were difficult to refine, heavy, sweet, and had high total acid numbers; some of these were exported.

Expanding crude import requirements will maintain the pressure on Chinese companies to acquire new supplies overseas. Chinese import requirements will grow in this decade to proportions that would justify accessing supplies from all major exporting regions. China’s crude imports include a disproportionate reliance on sweeter crudes, by Asian standards, with greater distillate yields.

China’s domestic product balance is short on distillates and long on gasoline, which must be exported. China’s refiners will probably try to decrease their reliance on the more costly, sweet crudes by investing in more hydrocracking capacity, a situation that exists in many current refining projects.

Projects

Sinopec and CNPC have vigorously expanded refinery production capacity. Historically, foreign participation projects have not resulted in positive results for those companies seeking to make investments. Petrochemical projects have advanced more rapidly than refining and marketing projects, although the pace of project development seems to have quickened in the past year.

Table 1 shows projects that will add about 1.8 million b/d of refining capacity. About 1.2 million b/d of additional capacity is needed to satisfy domestic refining requirements.

Chinese projects are often developed with little fanfare; substantial additional capacity could come online in the next 5 years. Those additional projects are likely to occur as expansions in existing plants. China refining companies could also develop new international projects this decade.

While increasing its refining capacity, China is also improving its petroleum trade infrastructure. China has historically had difficulty with shallow-port depths and inadequate infrastructure to handle imported products.

Substantial marine infrastructure projects, including deepwater berths, are being installed near Shanghai and other ports. That infrastructure will tend to lower the barriers to importing products and reduce costs for importers and their customers.

Small refiners

China has a peculiar system of small refiners, other than CNPC and Sinopec, often referred to as “social refiners.” These refiners include mostly small companies, often owned by regional or municipal governments but also by entrepreneurs.

These refiners are generally so disfavored by China that the central government has announced their closure more than once. The social refiners, however, have their supporters including companies that find them useful supply alternatives to the major oil companies. CNOOC acquires bitumen from such refiners under contract and, in exchange, supplies some crude.

The social refiners are currently experiencing tremendously low margins. The Chinese government, mostly in an attempt to dampen inflationary pressures, has imposed price controls on petroleum products at levels appreciably below international levels.

Those price controls have lowered refining profits for Sinopec and CNPC, which must acquire crude internationally or from CNOOC to supplement their own onshore production. These price controls, however, are far harsher for the social refiners that are not integrated with the upstream industry.

The demise of social refiners has been predicted more than once. A historical feature of refining is that bankruptcy destroys companies but often does not destroy the refining assets. The social refiners will probably survive the recent downturn.

China’s price policy, which is so devastating to refinery margins, will probably not last long. The same pricing policy that harms the social refiners also makes it difficult for other refiners to supply the country with fuel.

Shortfalls, especially of diesel fuel, are common in some areas, particularly the rapidly growing southern China. Major refiners also have negative profits when they process imported crudes with these pricing policies.

Power companies with oil-fired generators may have difficulty accessing adequate fuel supplies, which would exacerbate power shortfalls in the summer. China will need to relax this policy, which would lessen the pressure on the social refiners and perhaps allow them to expand operations.✦

The author

John H. Vautrain (jhvautrain@ purvingertz.com) is vice-president and director for Purvin & Gertz Inc., Singapore. Before joining Purvin & Gertz in 1981, he worked for Phillips Petroleum Co. and Union Carbide Corp. Vautrain was manager of Purvin & Gertz’s Long Beach, Calif., office 1987-2000. Elected director in 1997, he has been based in Singapore since 2000. His Asian consulting activities include crude marketing, petroleum refining, LPG, natural gas, and LNG. Vautrain holds a BA in chemistry from the University of Texas and an ME in chemical engineering from the University of Utah. He is a member of the International Association for Energy Economics, SPE, and AIChE.