Europe looks for supply diversity in the Caspian, Persian Gulf

Declining indigenous gas production is the biggest issue facing the European natural gas industry because it is leading to an increased reliance by consumers on supplies from geographically remote producers.

Of the world’s gas resources, 40% lies in the Caspian and Persian Gulf states, thousands of miles from 20% of the world’s gas consumers in Europe (Fig. 1). The questions are: How much of this gas will be brought to the European market, in what forms, and by which routes?

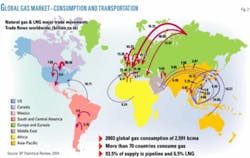

Despite the rise of LNG, the majority of the world’s gas consumption (93.5% in 2003) is satisfied by connecting consumers with natural gas resources by pipelines (Fig. 2). Gas pipeline dominance as a route to market is likely to be maintained in the short term.

Several major long-distance gas pipelines recently have been brought into operation or are at an advanced stage of project planning. The world continues to invest billions of dollars in new long-distance pipelines because:

- As indigenous resources in developed countries continue to decline, gas from further afield must be developed.

- Large-diameter pipelines can continue to be cost-competitive with LNG even over thousands of miles.

- Technological advances, i.e., new high-strength steels and automated laying and welding techniques, can result in significant pipeline-cost reductions that are likely to continue to ensure the competitiveness of pipelines.

What will it take to connect the Caspian and gulf regions to Europe by pipeline? Developments are required in three broad areas: political will, market liberalization, and economics.

The Caspian and gulf are complex areas from a geopolitical point of view; however, Europe’s desire for supply diversification, the prevention of economic dominance by any one supplier, and resource owners’ needs to bring their products to market provide strong drivers for political solutions.

Many of the gas markets along proposed pipeline routes are undergoing structural changes, and some are not readily accessible by alternative gas supplies. That means the development of another transit pipeline to Europe is a good possibility. But it will take both gas-market liberalization and political will to encourage investment and stimulate market growth.

The extension eastwards of the European Union and its policy instruments provides a driver for market reform. Private capital will be essential because any pipeline project will require massive capital investment running into billions of dollars. Such capital will require adequate returns; therefore, any project must be economically sound.

Supply, demand

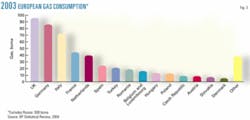

Most analysts are now predicting European gas consumption will continue to grow at 2-3%/year until at least 2015, driven largely by combined-cycle gas turbines for power generation. Such demand growth should, in general, be supported by environmental regulations, including emissions-trading mechanisms. Combined-cycle gas turbines could, however, be threatened to some extent by coal and a resurgence of nuclear power.

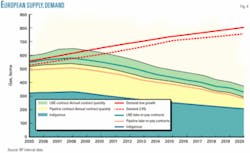

Nevertheless, it is not unreasonable to suppose that European gas consumption will increase to as much as 800 billion cu m/year (bcmy) by 2020 from 508 bcmy in 2003 (Figs. 3 and 4). Fig. 4 also illustrates how Europe will be supplied by a combination of indigenous production and existing natural gas and LNG contracts.

Declining UK and other indigenous gas production will lead to a growing supply-demand gap in Europe, which may reach 200 bcmy by 2015 and as much as 400 bcmy by 2020. Some of this gap will, of course, be filled by extending existing gas supply contracts.

The magnitude of the gap, however, is likely to ensure that there will be a growing customer base for additional gas supply sources. This demand must be satisfied and the gap filled.

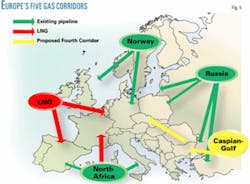

Fig. 5 illustrates Europe’s so-called five gas supply “corridors”: Norwegian and UK pipeline gas, North African pipeline gas, Russian pipeline gas, LNG from a range of sources, and the proposed “Fourth Corridor” pipeline gas from the Caspian and gulf.

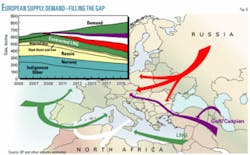

It is likely that Europe’s future supply-demand gap will be filled by some combination of new supplies from Russia, North Africa, and the Caspian and gulf through long-distance pipelines and LNG. Fig. 6 gives a projection of how this gap could be filled, utilizing a combination of BP PLC and other industry estimates.

In principle, there is sufficient room in Europe for new Russian, African, and gulf/Caspian pipeline gas and LNG. The exact mix will in large part depend upon the economics of the various alternatives.

Caspian and gulf pipeline gas and the Fourth Corridor will thus have to compete with the four existing supply sources. This will partly be determined by the availability of the gas resources in this region.

Caspian, gulf resources

The Caspian and gulf reserve base is enormous and far exceeds that required to satisfy domestic demand. Some 6 trillion cu m (tcm) of proven gas reserves are available to the three states east and west of the Caspian Sea, and some 70 tcm are available in the gulf. One important point to note is that the southwest Caspian discovered-gas resource base currently is probably insufficient to support a new pipeline corridor to Europe. Thus, additional gas from the East Caspian via a trans-Caspian pipeline and-or gulf gas will be required to ensure the viability of the Fourth Corridor.

In the case of the Caspian, these reserves could go to market via a pipeline west to Europe, but there are other options such as north to Russia, south to Iran, and east to Asia. Gulf gas could also go west by pipeline to Europe or north to Russia and east to Asia. In addition, gulf states have the option to bring their gas to market via LNG.

Fourth corridor

Three basic pipeline routes to Europe from the Caspian and gulf have been proposed:

- Turkey to Italy via Greece.

- Turkey to Austria via the western Balkans.

- Turkey to Austria via Bulgaria, Romania, and Hungary.

Each of these routes has its own promoters, concepts, technical challenges, cost bases, and transit markets.

The first essentially makes use of an existing and expanded infrastructure-as well as some new-build, and possibly physical swaps-to bring Caspian and gulf gas to Italy via Turkey and Greece.

Edison SPA in Italy and Public Gas Corp. (DEPA) in Greece are completing a feasibility study with EU funding. The project would require, in addition to the Turkey-Greece interconnector currently about to begin construction, building a new 500-mile pipeline (about one-third subsea) from Greece to Italy with a capacity of about 10 bcmy starting in 2010 at a cost of about $1 billion. The economic viability of such a scheme, however, is still being studied.

Although this project could make a significant contribution to Europe’s energy supply, its somewhat limited proposed volume throughput and its reliance on a combination of existing infrastructure and debottlenecking-as well as new-build-means that it should not really be considered as a major new gas supply corridor to Europe but rather an extension to the existing system.

Also, this project will have to compete with LNG projects being promoted in southern Italy and with expansions of the existing pipeline system from Tunisia to Italy.

The second project is sponsored by a consortium of companies from the West Balkans but is not as advanced as the other two options and faces the additional challenge of having more limited gas-market availability in the relevant transit countries.

Project costs and timetables are uncertain at this stage, but costs are likely to be at least as great as Turkey-to-Austria via Bulgaria, Romania, and Hungary.

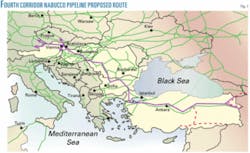

The final option, the so-called “Nabucco project,” is led by OMV AG, Austria, with the participation of Turkish, Bulgarian, Romanian, and Hungarian companies. The EU-funded feasibility study is nearing completion. Fig. 7 shows the proposed route.

It would require building a new 2,000-mile pipeline with capacity of up to 31 bcmy at a cost of some $6 billion. Up to half of that throughput capacity could service transit-country demand with the remainder reaching the Central European Gas Hub at Baumgarten, Austria. First gas is currently targeted for 2011.

If built, the line would represent a new gas-supply corridor: the “Fourth Corridor.” But can it be cost competitive with the other supply corridors?

Economics of five corridors

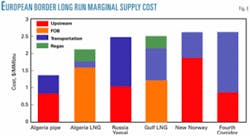

Fig. 8 shows the long-run marginal cost of supply for Norwegian, North African, Russian, and Fourth Corridor pipeline gas to the European border. The corresponding costs are also shown for African and gulf LNG. As illustration only for each of these calculations, common, consistent assumptions have been used for returns on capital for both upstream developments and downstream infrastructure (pipelines or LNG).

The calculations show the relative costs for each corridor; in practice, absolute costs may vary depending upon a variety of factors. It is also assumed that new infrastructure will be required for each option so that the comparison is on a like-for-like basis.

Note that even though some of the potential European supply-demand gap could be filled by expanding existing infrastructure-for example in Russia-in practice it will not be possible to fill all of the gap in this way. Thus, ultimately the Fourth Corridor must compete economically with any new-build infrastructure of the other corridors, both pipeline and LNG.

Not surprisingly, Algerian gas shows the lowest cost of supply to Europe. We can expect in the future, therefore, an increase in Algerian supply in the form of either pipeline gas and-or LNG. It is very unlikely, however, that Algeria alone will fill the gap because the overall resource base in Algeria (4.5 tcm proved reserves) will be insufficient and because of the European desire for competition and diversity of supply.

With 2.5 tcm proved reserves, Norway also does not have the indigenous resource base fully to fill the growing supply-demand gap. Hence, even though Norwegian cost of supply is comparable to the Fourth Corridor, in practice the Fourth Corridor’s main competitors can be considered to be pipeline gas from both North Africa and Russia and LNG.

We can see from Fig. 8 that the remaining three routes to market-new Russian pipeline gas, gulf LNG, and the Fourth Corridor-are roughly comparable from a long-run marginal cost point of view. The Fourth Corridor can thus be considered to be both competitive and economic.

Caspian, gulf alternative routes

We have seen that gas from this region can go to Europe via a Fourth Corridor pipeline that could compete economically with the other four gas corridors. Other options exist, however, for Caspian and gulf resource owners to bring their gas to alternative markets by pipeline: north to Russia, east to Asia and, in the case of the Caspian, south to Iran.

Will these options be more attractive for the resource owners? Gulf supply-demand forecasts are based on 4%/year growth, which is consistent with many analysts’ projections. Even if the combined demand grows to 400 bcmy by 2015, the potential production based on the known reserves base far outstrips domestic demand. Resource owners will thus look for export projects to monetize their gas.

Russia is a viable market for Caspian and gulf gas, not only to satisfy growing Russian domestic demand, but also to feed its export business to Europe. One can imagine physical swaps whereby Caspian and gulf gas flows north and then west to Europe, while East Siberian gas moves west to satisfy domestic demand.

That would certainly help optimize the current Russian pipeline transportation system. We again must recognize, however, the potential magnitude of Europe’s supply-demand gap of hundreds of billion cu m/year. No optimization of the existing Russian system can satisfy such increased demand; new Russian long-distance pipeline infrastructure, therefore, would have to be built to Europe if this route were chosen by Caspian and gulf resource owners.

This is not necessarily more competitive than building the proposed Fourth Corridor. In addition, the latter has the advantage of increasing supply competition to Europe, rather than relying on a potential dominant supplier that would potentially be able to dictate the terms of any gas sale from the Caspian and the gulf to Europe.

As already discussed, there is currently insufficient southwestern Caspian gas to fill a major Fourth Corridor pipeline to Europe, and gas from the eastern Caspian would require a 200-750 mile trans-Caspian pipeline (the exact length depending on the capacity of the existing Turkmen lines) at a cost of about $0.5-1.5 billion (depending on the length of the line).

Thus, Caspian resource owners could optimize their positions by selling gas to the large and growing markets in the north to Russia and in the south to Iran, which in turn could then expand their export businesses to Europe either by new pipelines (Russia) or LNG (Iran). While this certainly could be a viable economic option for Caspian resource owners, as discussed previously for Russia, given the size of the European supply-demand gap and the gas resource in the gulf region, the fundamental economic and competitive logic of building a Fourth Corridor remains.

Moving gas east to China’s growing gas market appears to be too challenging from an economic point of view. First, most of the demand lies in the coastal regions of eastern China. That increases to about 1,350-3,300 miles the distances gulf and Caspian gas would have to travel to market (the former being to connect with the West-East pipeline from southeastern Turkmenistan and the latter being a direct pipeline from southeastern Turkmenistan to Shanghai).

Indigenous production from western China currently flows to market by the 2,500-mile West-East pipeline, and there are options to enhance the capacity of this route. Russian pipeline gas, for example from the giant Kovykta field in East Siberia, is much closer (about 2,200 miles). In addition, the cost of supply of LNG from the gulf, Indonesia, and Australasia is likely to be much more competitive than a pipeline route from the Caspian and gulf.

Fourth Corridor competition

A very large and growing gas supply-demand gap is likely to exist in Europe after 2010, and sufficient gas resources exist in the Caspian and gulf regions to fill a significant part of this gap. A large new pipeline from this region to European markets is likely to be economically competitive with the existing gas supply corridors.

Such a pipeline could improve the competitive dynamics for both European customers and Caspian and gulf resource owners. For these resource owners, the Fourth Corridor is likely to be at least as attractive economically as other market options. A Fourth Corridor to Europe requires not only economic viability but also political will and regulatory developments stretching from the subsurface in the resource owners’ countries, through all the many transit countries, to the end-use customers in consuming nations.

Such developments are unlikely to happen quickly, and most parties involved now have other alternatives. Despite recent favorable developments, such as high-level European political support and serious feasibility studies and plans, the ultimate construction of a Fourth Corridor cannot yet be regarded as certain. Continued progress on economic, political, and regulatory fronts, however, could ultimately lead to interested parties concluding that the key question regarding the Fourth Corridor is not if it will be built, but when.

Based on a presentation to Gastech 2005, Mar. 16, 2005, Bilbao, Spain.

The author

Tom Quigley ([email protected]) is managing director, BP Gas & Power, Mediterranean, in Madrid. He joined BP in 1982 and spent 5 years in R&D working principally in exploration and production. That was followed by a 2-year assignment as commercial analyst for BP’s Far Eastern exploration program. Quigley later was appointed R&D manager for health, safety, and environment working principally for BP’s chemicals and oil segments. Quigley has extensive operating experience as a manufacturing manager for BP’s chemicals stream and as operations manager in BP’s oil fields in Colombia. In 1999, Quigley completed a year at Stanford University where he was awarded a Sloan Master of Science in management. He then became a vice-president of technology for BP’s gas and power business. Quigley holds a BS in physics from Leicester University and a PhD in theoretical physics from Oxford University.