CASPIAN OIL OUTLOOK-2: Caspian nations pursuing oil exports at greatly varying paces

This is the second of two parts on the outlook for oil exports from countries that border the Caspian Sea.

Gushers and dry holes

With the battle for pipelines essentially over, international oil companies (IOCs) and regional governments can get down to the business of actually pumping out the Caspian’s oil potential.

Numerous projects are under way, the majority of which are being led by foreign energy companies. Yet after a number of drilling disappointments in the southern Caspian Sea, including several dry holes, some projects in Azerbaijan have already closed down.

Other projects, such as the elephantine Kashagan field off Kazakhstan, appear set to live up to the hype. Still, only a handful of major projects will provide the bulk of the new oil emanating from the Caspian region (Table 2).

null

Kazakhstan: still to bloom

No state represents the potential of the Caspian region better than Kazakhstan. The country’s vast proved oil reserves were largely untapped in the Soviet era, and the discovery of the massive Kashagan field in 1999-the largest oilfield discovery in the world for 30 years-in shallow water of the North Caspian has only added to its allure..

Yet Kazakhstan’s offshore is largely unexplored, and the much-vaunted “Caspian Development Programme” has been derailed by a restrictive production-sharing agreement (PSA) regime and a new tax policy in 2004 that foreign energy companies say has hampered investment.

Still, Kazakhstan’s potentially voluminous offshore oil reserves have made it the most attractive investment destination in the Caspian region for IOCs. Its main Caspian project already in production is at Tengiz oil field on the eastern shore, developed by Tengizchevroil (TCO), a Chevron-led consortium, with estimated recoverable reserves of 7-9 billion bbl.

The $3 billion second generation and sour gas injection (SGP/SGI) expansion finally went forward in January 2003 after a dispute over financing of the project, and output at the field rose to 270,000 b/d by the end of 2004. Production is slated to reach 750,000 b/d by the end of the decade and could top out at 1 million b/d by 2012 under the right economic conditions.

Although not technically a “Caspian project,” the development of its Karachaganak gas-condensate field on the Russian-Kazakh border is nonetheless a key energy project for Kazakhstan. Led by BG Group, the Karachaganak Petroleum Operating BV (KPO) consortium has focused on extracting liquid hydrocarbons in the initial stages of the field’s development.

A pipeline connection to the CPC’s Tengiz-Novorossiisk pipeline, completed in 2003, has given the consortium an export outlet for its condensate output, although a problem with contamination forced KPO to push back exports via the CPC until mid-2004.

KPO is producing 100,000 b/d in condensate with plans to increase that total to 140,000 b/d, although Phase III development of the field will focus on gas extraction. Karachaganak condensate exports eventually could be redirected to China once the Kazakhstan-China pipeline is completed.

The aforementioned Kashagan project is Kazakhstan’s first major offshore oil field development, and its massive size-with an estimated 38 billion bbl in proved reserves, including at least 7 billion to 9 billion bbl recoverable-has stimulated significant IOC interest in the offshore development program.

Due to its massive production potential and obvious importance-both to Kazakhstan and global oil supply-the project has been delayed by a series of setbacks as the government and the consortium developing the field, the Agip Kazakhstan North Caspian Operating Co. (Agip KCO), have argued over plans for developing Kashagan.

An original timetable for the start of oil production in 2005 proved untenable, prompting the government to demand compensation from Agip KCO, led by Italy’s Eni, before consenting to a delay in the start of production. The new timetable for production envisions first oil in 2007-08 at 75,000 b/d, rising quickly to 450,000 b/d by 2010, then to 900,000 b/d by 2013, and finally hitting a plateau output of 1.2 million b/d by 2016.

Recently, five of the existing members of Agip KCO struck an agreement-after protracted negotiations-with the government to divide up BG Group’s 16.67% stake in the project among them, with Kazmunaigaz getting an 8.33% stake to give the state a direct role in Kashagan.

Several more oil projects in the Kazakh sector of the North Caspian are in the very early stages, with talks still continuing over fields such as Isatai, Zhemchuzhina, and Zhambyl. In addition, Russia and Kazakhstan have agreed to jointly develop the 7.33 billion bbl Kurmangazy field, which lies in the Kazakh sector of the sea but straddles the Russia-Kazakh border. However, a deal on a PSA for the field has been delayed over Rosneft’s concerns over the Kazakh fiscal regime, even as Kazmunaigaz is ready to bring in France’s Total as operator of the project.

The Kurmangazy dispute epitomizes the Kazakhstan dilemma for foreign oil companies: a massive oil field that holds much untapped potential but an overbearing government eager to dictate the terms and pace of development.

Kazakhstan is hoping to treble its current production of 1.2 million b/d by 2015, but government interference is beginning to hinder foreign investment. In turn, the government is increasingly turning to state-to-state oilfield development deals rather than open tenders for its offshore blocks.

Kazakhstan will need additional export outlets, as well as perhaps a more conciliatory approach to foreign investors, if it is to catapult into the superleague of world oil producers in the next decade (Table 3).

null

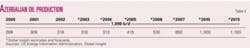

Azerbaijan: boom, then bust?

Once seen as the jewel in the Caspian crown, Azerbaijan is proving that much of the 1990s hype surrounding the Caspian is overblown.

A series of high-profile drilling disappointments in the Azeri sector of the Caspian Sea left several IOCs high and dry, though the Azeri government continued to promote the country’s offshore potential all the while. The result has been a distinct shift northwards in foreign investment in the region, leaving Azerbaijan scrambling to convince energy companies to continue drilling while hoping for another major discovery.

For Azerbaijan, one of the oldest hydrocarbon-producing regions in the world, the 21st century oil boom starts-and may end-with the exploitation of the ACG structure. The BP-led AIOC signed the 30-year, $8 billion “contract of the century” in 1994, and initial oil production began in 1997, but 2005 marks a turning point for the project.

With the BTC pipeline slated to come on stream later this year (initial exports from Ceyhan are expected in the fourth quarter following the pipeline’s official commissioning in May 2005), AIOC has begun to ramp up production at the structure, which stood at 130,000 b/d at the end of 2004.

The start of production at Central Azeri field in February 2005 has already ratcheted up output to around 165,000 b/d through March, and production for 2005 is expected to rise to around 220,000 b/d.

With West Azeri field scheduled to come on stream in 2006, AIOC is expecting output to increase to 424,000 b/d of oil, then to 754,000 b/d in 2007 with the first oil from East Azeri field. The final phase of the ACG project, development of deepwater Guneshli field in 2008, is expected to push AIOC’s oil production past the 1 million b/d level in 2008 with 1.046 million b/d once the field is brought on stream.

However, AIOC’s development plans for the 5.4-billion-bbl ACG structure envision a sharp dropoff in production after hitting peak output. The ACG fields will see production taper off to 800,000 b/d early in the next decade before a steep decline starts, with output leveling off at between 250,000 and 300,000 b/d by 2020 (Table 4).

Now that Azerbaijan’s oil boom has finally arrived, however, the government needs other projects to sustain that boom, but the prospects thus far are not good. High hopes for offshore projects at the Lenkoran-Talysh, Oguz, Apsheron, and Ateshgah blocks were dashed by drilling failures, and each of those projects has closed.

Similarly, ExxonMobil’s inability to find commercial hydrocarbon reserves at either the Zafar-Mashal structure or the Nakhichevan block means that these two projects are effectively dead as well.

Just as Azerbaijan’s long-awaited return to world oil prominence is kicking off, the country is staring directly into the abyss in the absence of another major discovery.

Azerbaijan still has hope, however, that several fields could dispel the notion that the country is all hype, no substance. For example, Lukoil is drilling the Yalama block in the northern part of the Azeri section of the Caspian Sea. In addition, the country stands to benefit greatly from a multilateral accord on the legal status of the Caspian Sea-if only the littoral states could agree to one.

Several prospects in disputed waters near the Azeri-Iranian and Azeri-Turkmen maritime borders could see significant investment if the legal uncertainty about their ownership is removed. In particular, the Araz-Alov-Sharg structure, with an estimated 6.6 billion bbl in reserves, could be a major boon for Azerbaijan’s oil industry.

A joint development deal between Azerbaijan and Iran, along the lines of the Russian-Kazakh agreement in the North Caspian, could open up the structure for development, but in the absence of such an agreement, Azerbaijan will increasingly rely on the ACG project to drive its oil production.

Turkmenistan: frozen in time

Over the course of the past 14 years, independent Turkmenistan has distinguished itself among the ex-Soviet Caspian nations as a virtual black hole of foreign investment.

Not only are the estimated oil reserves in its sector of the Caspian Sea thought to be substantially smaller than those of Azerbaijan or Kazakhstan, but Turkmenistan has also done a far better job of repelling foreign investment than it has of attracting it.

The central Asian republic inherited a bloated bureaucracy from the Soviet era, but under President Saparmurad Niyazov (also known as “Turkmenbashi,” or “Father of the Turkmen”), the investment climate has perhaps even worsened.

Niyazov, who was appointed president-for-life in 1999 by the rubber-stamp Turkmen legislature, has exhibited a knack for erratic policymaking and micromanagement of the economy, fostering a wildly unpredictable investment climate, complete with arcane regulations and constantly changing administrative requirements.

The absence of political or economic reforms gives Turkmenistan the aura of a mini-Soviet planned economy, pre-collapse. The majority of international energy companies who dared venture into the murky world of Turkmenistan in the 1990s have departed, leaving only a handful behind.

Still, those few companies that have found themselves on Niyazov’s good side have managed to carve out a small niche in the country’s Caspian shelf. Dragon Oil, a company based in the United Arab Emirates, has the rights to the Cheleken contract area on the shoreline, and the company’s extensive well workover and continuous drilling program have boosted production above 20,000 b/d.

Petronas, the Malaysian state oil company drilling at Makhtumkuli-3A field (also known as East Livanov), announced encouraging results earlier this year with plans to begin production by late 2005. Furthermore, the UK’s Burren Energy is continuing to produce oil from the onshore Burun field under the Nebit Dag PSA with Turkmenistan.

Despite the shoddy investment climate and the “reputational risk” to IOCs from Turkmenistan’s awful human rights record, investment dollars in the country’s oil sector are actually on the rise, led by Russian companies but also including well-known players such as Denmark’s Maersk Oil and lesser-known Western companies such as Canada’s Buried Hill Energy.

A consortium of Russian companies, including Zarubezhneft, Rosneft, and Itera, are still negotiating details for the Zarit PSA, while Gazprom and Lukoil are also seeking to develop oil fields in the Turkmen sector of the Caspian.

Maersk signed a PSA for offshore blocks in October 2002, while Buried Hill enlisted the services of former Canadian prime minister Jean Chretien to secure rights to Serdar field. However, Azerbaijan, which also claims the field but calls it Kyapaz, has raised objections to the licensing of the field, threatening retaliation against Canada.

Given the dictatorial nature of the Niyazov regime-as well as the uncertainty in the investment climate-Turkmenistan will struggle to attract larger levels of foreign investment, making it nearly impossible to achieve Turkmenbashi’s ambitious production growth targets.

Although Turkmenistan has substantial gas reserves, the country has comparatively small oil resources, and the goal of 2 million b/d in oil output by 2020 looks unobtainable, especially given current production of just over 200,000 b/d (Table 5).

In the absence of direct access to export markets or further market-oriented reforms, foreign investment in Turkmenistan’s oil sector will remain limited, which in turn will put a ceiling on Turkmenistan’s ability to significantly increase its oil production.

Russia: another oil patch

For Russia, the Caspian Sea represents just one of a number of emerging oil regions.

The Russian sector of the sea has been largely unexplored, with the Kremlin (Russia’s presidential administration) and Russian oil majors instead placing emphasis on efforts to exploit existing fields in Western Siberia, which has a well-developed system of infrastructure already in place.

Foreign investment in the Russian oil industry has concentrated thus far on Sakhalin Island in the Far East and the Russian Arctic, as well as Western Siberia. Eastern Siberia is beginning to come into focus as the government seeks to license new oil fields and develop the region, but the Caspian region is largely the purview of Russian companies.

Russia was an active participant in the Caspian oil and gas pipeline battles of the 1990s, but the government is beginning to emphasize exploration and development of its sector of the Caspian. A 2002 agreement with Kazakhstan on the division of the North Caspian Sea provides the framework underpinning cooperation and joint development of Khvalynskoye and Tsentralnoye fields, which lie mainly in Russian waters.

Russia’s Lukoil was appointed by the government to represent the country in the joint development projects, and the oil major has formed a joint venture, TsentrKaspNeftegaz, with Gazprom to develop Tsentralnoye field along with Kazmunaigaz, the Kazakh state oil and gas company.

Lukoil and Kazmunaigaz agreed on a timetable of 2007-08 for initial oil production from the field, but given that the project remains in its initial stages, this is obviously unrealistic. In March 2005, Lukoil formed a JV, the Caspian Oil & Gas Co., directly with Kazmunaigaz in order to undertake development of Khvalynskoye field.

Despite these tentative steps forward, Russia’s exploration and development of its part of the Caspian Sea will likely remain on the back burner in the short term as foreign investors remain wary of the Kremlin’s increasingly interventionist approach to the Russian natural resources sector.

The long-running “Yukos affair” continues to cast a shadow over the Russian oil industry, especially in the wake of the verdict in the trial of former Yukos CEO Mikhail Khodorkovsky. Despite the cancellation of the state’s plans to merge Gazprom and Rosneft, the Russian government’s determination to acquire a majority stake in Gazprom and regain control of the gas giant indicates the state’s desire to play an even more direct role in the development of Russia’s oil and gas reserves.

Oil reserves in the Russian sector of the Caspian, therefore, are likely to remain an exclusively Russian play (with Kazmunaigaz along for the ride with the bilateral deal to divide the North Caspian).

The Kremlin will likely dictate the pace of development of the Russian sector of the Caspian in line with state political and economic objectives. Regardless, the Caspian’s contribution to Russia’s overall oil production will remain minimal for the foreseeable future.

Iran: delay tactics

Iran has taken a rejectionnist stand on Caspian development by the other littoral states to date, holding out for one-fifth of the sea’s resources.

Kazakhstan, Azerbaijan, and Russia have backed the division of reserves based on length of coastline, which would give Iran only a 13% stake of the area resources, the smallest of the five states.

Iran has been fighting a losing battle against the other Caspian littoral states, basing its rationale for a division of the sea on early 20th-century agreements that hold little water given the emergence of the new states from the breakup of the Soviet empire.

Indeed, development work by the northern Caspian states has picked up since the Russia-Azerbaijan-Kazakhstan trilateral agreement of 2003, leaving Iran’s as a sole dissenting voice, with some occasional backing from Turkmenistan, which would receive an 18% stake under the median-line division.

However, Iranian resolve over an overall territorial division does seem to be slipping, at least in practical terms if not on the rhetorical level, where the 20% claim lives on. An aggressive drive to increase transit oil from existing Caspian developments is one sign of pragmatism from the Iranian side.

Iran has a goal of increasing its volume of oil transit to 1.6 million b/d by the end of the decade from some 110,000 b/d at the end of 2003. Some of this volume would necessarily come from offshore production. Energy cooperation between Iran and the former Soviet Caspian states is also increasing via new gas pipeline linkages and electricity connections.

Another sign of weakening Iranian resolve on this issue has been the government’s decision to commission seismic surveys and launch an exploratory drilling program in the near offshore area in 2005.

Iran is looking for additional oil reserves to meet ambitious production targets of 5 million b/d by end-2005-which appears unlikely given current capacity of 4 million b/d-and 7 million b/d by 2015.

With an estimated 300,000 b/d of oil production lost each year through field maturity and attrition, Iran will likely require Caspian development to bring onstream the resources necessary to supplement aging onshore and gulf oil fields, a point which seems to be gathering currency within the government.

Iran started construction of the Iran-Alborz drilling platform in the Caspian in 2004 to drill to depths of over 1,000 m, although technical problems have held up the start of exploration work. Foreign players are also being sounded out for Caspian work, including Petrobras and Statoil, in addition to engineering players, given the lack of experience by domestic Iranian companies in deep offshore exploration and production.

As initial exploration work continues and Iran reaps the rewards of Caspian oil development in other littoral states through transit trade and product imports, the country’s rejectionist stance is likely to become even less tenable. From Iran’s perspective, this leaves a widening gap for a negotiated settlement on an overall division of regional reserves and the eventual allocation of exploration and production acreage in the Iranian sector to foreign players.

Outlook and implications

Looking at the bottom line, what, if any, impact will Caspian region oil production have on global oil markets?

Going forward, the trend in oil markets is relatively simple: Demand is rising steadily, with supply struggling to keep pace.

Spare capacity is being squeezed, and with much of the world’s oil extracted in countries with unstable political environments, traders are bidding up prices as a result.

Demand growth has continued unabated in spite of higher prices, suggesting that demand is relatively inelastic and, unlike the oil shocks of the 1970s, rising oil prices are not snuffing out global economic growth.

Assuming oil consumption continues to rise in coming years by, say, a modest 1.8%/year rate, some 1 million to 1.5 million b/d of new oil supplies will be needed to satisfy demand. Factoring in declining production from mature existing basins in places like the continental US and the North Sea, some 2.5 to 3 million b/d of “new” oil will be needed.

Rebuilding spare capacity to quieten tempestuous markets in the event of a supply disruption will require an additional 500,000 to 1 million b/d in new oil production over a 5-year period, for example, raising the requirements for new oil supplies to perhaps 4 million b/d/year in order to balance the market in the future.

Can Caspian oil fill the void? The simple answer is no.

Given the projected oil volumes coming from the major established and planned projects-Tengiz, ACG, and Kashagan-the Caspian region could contribute an estimated 2.2 million b/d/year of oil to world markets by 2010.

Considering current output from these projects of around 535,000 b/d, this adds approximately 1.765 million b/d in “new oil” to the market 5 years from now-hardly enough to offset declining production elsewhere around the globe, let alone build spare capacity or even have the ability to impact prices.

Of course, some additional oil could emanate from the Caspian, notably from Karachaganak and probably from Petronas’s project in Turkmenistan, but these volumes are unlikely to add more than incremental supplies to the market.

Before dismissing Caspian oil’s impact on global oil supplies, however, it is useful to take a longer-term approach-and keep in mind the numerous wild cards involved in calculating the region’s future production.

The Tengiz, ACG, and Kashagan projects are projected to provide 3 million b/d of oil to global supplies by 2015, including some 2.57 million b/d in new oil. However, by 2015, the Kurmangazy, Khvalynskoye, and Tsentralnoye projects could all be onstream as well, adding to the region’s base of oil output.

Further development of the untapped Kazakh offshore reserves, combined with a potential lucky discovery in the Azeri sector of the Caspian, could provide further supplies-say an extra 1 million b/d in total. A multilateral agreement on the division of the Caspian could trigger investment in development of several disputed hydrocarbon structures in the southern Caspian and-given adequate export outlets-suddenly the Caspian region could actually contribute that desired 4 million b/d to oil markets in 2015.

However, this is still largely an optimistic scenario, driven by assumptions that history has not borne out. The succession of drilling failures in the Azeri sector of the Caspian does not bode well for future discoveries, and the ongoing dispute over the legal status of the sea-nearly 14 years since the breakup of the Soviet Union-does not augur well for a quick resolution that would open up new fields to exploitation.

While recent history in itself does not mean that the littoral states are precluded from reaching an agreement on the division of the sea’s resources, neither does it suggest that Azerbaijan, Iran, Kazakhstan, Russia, and Turkmenistan can resolve their differences and strike a deal acceptable to all parties.

Furthermore, the potential 4 million b/d in Caspian oil production to be added by 2015 is the sum total, not new oil per year. By itself, then, new Caspian oil will have little real impact on global markets, perhaps only helping to offset declining global production elsewhere.

In combination with other emerging oil supply centers such as West Africa, and Caspian region may help to balance out global markets, but if demand continues to rise at even a modest rate, these regions will still struggle to satiate the world’s appetite for new oil. By itself, and in the absence of a major supply disruption in the Middle East, Caspian oil will have no substantive impact on prices in the coming decade.

Hence, Western policymakers looking to the Caspian region to help bring down lofty oil prices will be sorely disappointed. Given the projected rise in demand, new oil emanating from the Caspian basin will have a hard time even reducing the world’s increasing dependence on “risky” Middle East oil. As such, OPEC will certainly gain more power as the world becomes more dependent on the producer cartel for oil supplies.

With OPEC apparently committed to a higher price band, oil prices look set to remain above $40/bbl. The hope among consuming countries that future Caspian oil supplies might serve as the catalyst to reduce oil prices in the coming decade appears overblown hype.

Not quite a dry hole, the Caspian region’s impact on world oil markets will certainly be no gusher, either.

Acknowledgment

Catherine Hunter and Simon Wardell contributed to this article.