The push to develop natural gas from the Arctic and other sources is being driven by declining deliverability, despite high levels of drilling activity in western Canada and the US.

Canadian operators drilled 19,851 wells in 2003, most targeting gas. The Petroleum Services Association of Canada has amplified its estimates several times and now expects 22,255 wells to be drilled in 2004. About 70% of the total are gas wells, but many are shallow producing wells that can be drilled quickly as companies act to cash in on high commodity prices.

Despite the record activity in the Western Canada Sedimentary Basin (WCSB) and the higher rate of drilling, flat or declining production is resulting. Statistics Canada said Canadian gas production fell 3.8% in 2003, and exports to the US fell by 5.6% to 9.83 bcfd. The decline in Alberta production was about 2% in 2003.

Canada's National Energy Board (NEB) reported that the overall WCSB decline rate increased to 23% in 2002 from 13% in 1992, and 3.8 bcf of production must be replaced each year to keep production flat. That replacement level has not been achieved since 2001. The board expects production to decline by 3%/year through 2005.

The US Energy Information Administration in its 2004 outlook and 25-year forecast reported that US gas demand would increase by an average 1.4%/year through 2025, and it cannot count on Canadian imports to fill the supply gap. EIA said imports from Canada would remain at about 3.6 tcf/year to 2010 and decline to 2.6 tcf by 2025.

The Canadian Gas Association (CGA) said there are abundant supplies of gas in Canada and North America, and the issue is adequate investment.

CGA Pres. Michael Cleland said tight supply must be eased by new investment in supply and delivery infrastructure. The association called on governments to streamline access and other permit procedures to create a "smarter regulatory framework" and make policies that encourage innovation and investment.

David J.Hughes of the Geological Survey of Canada said if supply-demand forecasts are to be believed, there appear to be serious supply shortfalls in continental gas coming, and it is unlikely that Canada will be able to close the gap. Hughes said he expects Canadian gas deliverability to be flat at best or in a slight decline this year.

Other options

Hughes said in a paper to the Canadian Institute, however, that there is a portfolio of options and solutions to the supply gap:

- Increased conservation and efficiency in gas use.

- Importation of LNG, which is already factored into existing forecasts but which has geopolitical and NIMBY ("Not in my backyard") implications.

- Unconventional gas, also already factored in. This will play a major role in forecasts.

- Fuel switching to oil or coal. However, capacity is limited without new capital investment.

- Destruction of demand by movement of gas-intensive industries, such as fertilizer and petrochemical plants, offshore. This is now occurring, but it also has geopolitical implications.

Hughes said the bad news is that North America is on a gas production treadmill that requires ever more drilling to keep up with demand, and it looks as if that battle may be lost. The good news, he said, is that the gas price outlook remains good for the foreseeable future.

Exploration

Meanwhile, exploration activity is proceeding slowly in the Mackenzie Delta to prove up additional reserves to support the proposed Mackenzie Valley Pipeline. Exploration companies are faced with a problem of timing. A question for them is: How many costly drilling projects should be undertaken before a pipeline successfully negotiates the regulatory process and there is more certainty on the final timing, sizing of the line, and access to it?

Exploration is being conducted by an eight-company explorer group: ChevronTexaco, Petro-Canada, Encana Corp., BP PLC, Anadarko Canada Corp., Devon Canada Corp., Apache Canada Ltd., and Burlington Resources Canada Ltd.

Devon is the largest landholder in the area, with 1.8 million net acres in the Delta and Beaufort Sea areas. The company has interests with partner Petro-Canada in six leases onshore and interests in four exploration licenses in the Beaufort Sea. Devon has participated in six onshore wells and reported one discovery, the Tuk M18 well, which has estimated reserves of 200-300 bcf.

Petro-Canada is operator of one suspended well, the Nuna I-30. Devon also has conducted extensive 3D seismic offshore in preparation for a possible drilling project in the Beaufort Sea in winter 2005-06. Any offshore project will be subject to regulatory and corporate approvals. By drilling six wells Devon and its partner Petro-Canada have protected or extended permits on the bulk of their leases in the region.

Chevron Canada Resources and partners BP Canada and Burlington Resources Canada also have drilled several tests in the Delta. Chevron has interests in 21 significant discovery licenses in the Delta, the Beaufort Sea, and in Eagle Plains in the Yukon Territory.

Chevron spudded the Ellice I-48 test in March 73 miles northwest of Inuvik. Chevron said results of the test are confidential but described it as a natural gas prospect. The company has submitted regulatory applications and anticipates performing at least one exploration test and conducting additional seismic work this winter.

The North Langley K-30 well, 81 miles northwest of Inuvik, was spudded in March 2003 and tested at a restricted flow rate of 18 MMcfd from the Tertiary interval. It was the first well Chevron drilled in the region since the late 1980s.

In first quarter 2004, EnCana Corp. and partners Anadarko Corp and Conoco Phillips completed the Umiak N-16 test on Richards Island about 47 miles north of Inuvik. The company said it encountered hydrocarbons and that results are encouraging. Additional drilling is planned for the upcoming winter.

EnCana has a 37% interest in two exploratory blocks covering 529,000 gross acres and about 198,000 net acres in the Delta.

Michel Scott, vice-president of frontiers for Devon, said the question for explorers is whether to spend money now on exploration or wait until the availability of a pipeline is more assured. He said exploration companies want a pipeline to have as many access ramps as possible with flexibility for expansion and a shipper-friendly environment.

"You can't expect explorers to do all the drilling up front and take all the risks," he said.

The Devon executive said there is potential both onshore and offshore in the arctic region.

"There have been a total of 250 wells drilled, 160 onshore and 90 offshore, so we know there are accumulations up there," he said.

"According to [Canada's NEB], the area has potential for 65 tcf, with 50 tcf offshore. In our seismic work we see some very significant potential accumulations there."

Stakeholder concerns

Scott said Devon would not be involved unless there was a chance to get gas to market. He said the tight supply-demand balance and current gas prices suggest it is time to bring on new gas supplies, whether from frontier areas or from LNG.

"We are in a price zone which supports both. It is logical to see an area like the Mackenzie Delta tied in. It [the Mackenzie Valley pipeline] is really only an extension of the pipeline system in Canada and North America. It is not like trying to bring gas from Alaska, which is a gigantic project," he said.

The Devon executive said explorers have learned to be more careful in terms of timing expenditures because they don't control the timing of the pipeline.

"There is no point for us now going off and chasing smaller targets, until we can see the pipeline a little more clearly," he said.

"We fundamentally believe the time is ripe for the Mackenzie Valley. But there are still some hurdles—if the pipeline hearings do not go well, or if the local population doesn't want the project."

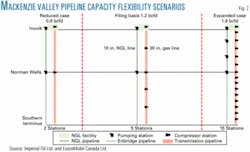

Scott said that in the absence of major new discoveries to date, it makes sense to plan the pipeline sizing with the flexibility to expand through compression. He said current exploration is a basin-opening project, and once it is opened it will spur much more exploration.

Greg Stringham, a vice-president with the Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers, said a slow exploration pace in the Delta is not a major concern at this time.

"Exploration can move faster than pipeline construction so I don't think exploration is going to be a critical path item. They will probably continue to explore and buy up lands and some of the companies are still proceeding with wells," Stringham said.

"But I think this slower pace will continue until probably near approval of [the pipeline] application or when the construction cycle starts. That gives them 3 years and enough time to get out in the field and get some exploration done."

The pipelines' progress

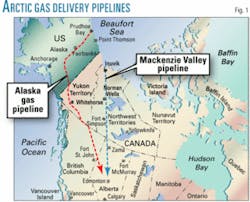

The consortium planning the Mackenzie Valley gas and natural gas liquids pipelines from Canada's Arctic to southern markets says the cost of the project has increased 40% to $7 billion (Can.) from $5 billion (Fig. 1).

The increased cost estimate was released earlier this month as the group filed an 8,000-page application with NEB and other regulators.

Toronto-based Imperial Oil Resources Ltd., lead member of the consortium, attributed the cost increases to more accurate estimates for development of three anchor gas fields in the Mackenzie Delta and the increased size of a planned gas processing plant near Inuvik, NWT, which will remove gas liquids.

Imperial spokesman Hart Searle said the group now has a much better understanding of costs for development of the three fields. The 758-mile gas transmission line would have an initial design capacity of 1.2 bcfd—expandable to accommodate gas from future fields (Fig. 2). It would connect in northern Alberta with existing pipeline systems operated by TransCanada PipeLines Ltd.

Reserves in the three anchor fields, Taglu, Parsons Lake, and Nignintgak are now estimated at 6.1 tcf. The project will include drilling 46 wells in these fields and laying gathering lines to a processing plant.

A proposed 295-mile natural gas liquids line parallel to the gas line will extend to Norman Wells, NWT. The liquids will be batched there for shipment south in a crude oil pipeline currently operated by Enbridge Inc.

Members of the consortium making the applications are Imperial, ConocoPhillips Canada, Shell Canada, ExxonMobil Canada, and the Aboriginal Pipeline Group (APG).

Imperial said it expects hearings to begin in 2005 and to take a minimum of 1 year to complete. If approved, the construction phase could take three winters, and gas could flow south in late 2009.

The consortium stressed that a final decision on the project would depend on the outcome of regulatory hearings, any conditions applied, and final cost estimates for the project. Imperial said other matters also have to be resolved, including finalization of benefits and access agreements, assessment of markets, and firm fiscal terms. It said these issues are essential to the development of a firm project schedule and critical to a final construction decision.

TransCanada buys in

In the meantime, Trans-Canada Pipelines Ltd., Calgary, has agreed to pursue extension of its Alberta pipeline system to connect with the Mackenzie line just south of the Alberta/NWT border, and in June it sought regulatory approval for funding and participation agreements that provide APG with an $80 million loan to help finance its share of planning costs. In return, TransCanada would obtain a 5% interest in the pipeline, and the producers have provisionally agreed to reduce their ownership share by 5% of anchor capacity at the time they take a decision to construct.

TransCanada also would have options to acquire additional interests if members of the producer group decided to sell or reduce their interests. The pipeline company would have an option to acquire 50% of any such interests.

Other members of the producer group would have opportunities to acquire the remaining 50%. Other financial terms would kick in as the project proceeds.

The agreement would give APG and Imperial each a one-third interest in the pipeline, and the remaining third would be held by the three other members of the producers group.

Bumps in the road

Although aboriginal groups support the project, the Deh Cho First Nations group in the Northwest Territories is seeking a court injunction against the pipeline, saying land claims have not been settled with Ottawa. It also is seeking to be included in a review panel for the pipeline. The group is located at the southern end of the likely pipeline route.

Most of the aboriginal people have signed on to the pipeline project, and APG represents their interests. Three other aboriginal groups who support the pipeline said they might counter-sue Deh Cho. Nellie Cournoyea, a former premier of the Northwest Territories, said the decision to choke the rest of the people could not be left up to a group that does not know what it wants.

Cornoyea is CEO of the Inuvialuit Regional Corp., which represents aboriginal business interests in the Arctic. She said the Deh Cho had no right to impede development.

Roland George, an analyst with Purvin and Gertz Inc., commented, "The Deh Cho are not so much against the pipeline as wanting to use it for leverage. These are things which are going to be bumps in the road."

Imperial spokesman Hart Searle said it is too early to say if the legal action would complicate the position on the pipeline application.

"It is very much premature [to speculate] on what might or might not happen. History would tell us that action on things like this is not instantaneous. This is not our process. We are not directly involved but we will continue to watch it closely."

Slow review process

The review process is expected to be long and complex. Regulatory hearings involving NEB and other agencies are expected to take 2 years. If approved, construction of the pipeline and related facilities would take 3 years. There have been complaints from some players that the regulatory process is lagging and needs to be streamlined.

Imperial CEO and Pres. Tim Hearn said he is concerned that bureaucratic requirements are delaying the pipeline project in reaching the construction stage. Hearn said speeding up the hearing process would not compromise environmental concerns.

TransCanada CEO Hal Kvisle said recently the slow pace of regulatory activity by Ottawa could derail the pipeline project if market conditions change.

"I continue to be frustrated that the time required to build aUcomplicated pipeline is a small fraction of the time taken to get through what I can only describe as ponderous regulatory and approval processes," he said.

Kvisle said Ottawa seems in no hurry to resolve the long-standing unsettled land claims and rights-of-way issues. A Mackenzie Valley pipeline could be built in about 18 months after a regulatory green light for construction, he said, but the big issue is how long it is going to take to get the green light.

George said it is unknown what interveners will do at hearings but several environmental groups are expected to participate, and hearings could be adversarial.

"Some of them are fairly antidevelopment. With others, it's more a question of sustainable development. It's the NIMBY bunch who are going to be participating who could make life interesting." George said.

Alaska Highway pipeline

Both TransCanada and Enbridge Inc., Canada's largest pipeline companies, have indicated interest in construction of segments of the proposed Alaska Highway gas pipeline from Prudhoe Bay.

TransCanada has said it is in talks with Alaska to build the state's leg of the pipeline. The company controls much of the right-of-way for the line, which is far in the future. Enbridge announced earlier this year that it has filed an application with the state to negotiate commercial agreements for the construction and operation of the segment of the Alaska Highway line proposed to be built in the state.

The two companies are also involved in separate proposals with partners for LNG terminals in Quebec.

British Columbia

Northeastern British Columbia is another area, in addition to the arctic, that offers the prospect of additional gas reserves in western Canada.

A number of heavyweight companies, including EnCana Corp., Talisman Energy Inc., Canadian Natural Resources Ltd., BP PLC, Burlington Resources, and Anadarko Canada, are all seeking deeper gas finds in the region.

EnCana recently spent $500 million to acquire rights in the Cutbank Ridge area and estimates 4 tcf of recoverable gas in the region, about 30 miles southwest of Dawson Creek, BC. The company acquired 150,000 net acres and has a preliminary development plan to drill 100-200 wells/year.

Alberta's oil sands

An unanswered question is how much demand rapidly expanding oil sands development in northern Alberta will place on new gas supply from the arctic.

A recent study by the Canadian Energy Research Institute (CERI) said a moderate growth scenario based on pricing of West Texas Intermediate oil at $25/bbl at Cushing, Okla., would see oil sands production increase to 2.2 million b/d by 2017 from more than 1 million b/d.

Robert Dunbar, CERI research director, said that natural gas feedstock demand for oil sands by 2017 could be 1.5-2.2 bcfd. He noted, however, that the industry is actively seeking ways to reduce reliance on natural gas.

A number of alternates are being investigated, including gas produced from bitumen, nuclear energy, and improved technology.

Dunbar said the oil sands would compete with other North American gas consumers for gas supplies.

Michel Scott of Devon said that, at the end of the day, any unit of gas that comes in from the frontiers is going into a total supply pool that is available to North America regardless of where the molecules go. Scott said any increase in oil sands production would likely be there whether or not gas was coming from the frontiers.

"I don't link the two. It is just the law of supply and demand. As gas prices firm up, those people who chase oil sands and heavy oil are going to be looking at other methods to sweep the oil sands out of the reservoir. Gas is getting pretty expensive," Scott said.

Greg Stringham of CAPP said oil sands operators are looking at a number of different alternatives to natural gas as a feedstock for in situ recovery. He said the oil sands would still require some Mackenzie pipeline gas.