Petroleos de Venezuela SA, Venezuela's state-run oil company, has embarked on an aggressive campaign to restore its credibility in the eyes of the world.

After suffering a debilitating strike that saw an almost complete shutdown of its operations a year ago and that resulted in the loss of nearly half of its employees, the state firm insists it has all but fully recovered. The strike was the culmination of growing opposition to Venezuelan President Hugo Chávez's efforts to impose a new leadership at the state company that would be friendlier to his regime. The strike started in the oil sector but spread throughout much of the country's business and professional classes. Those groups led an uprising against what the strikers still claim is the fiery populist's agenda to establish a Cuban-style socialist dictatorship in the most important hydrocarbon exporting nation in the Western Hemisphere.

Last year, long-simmering opposition to Chàvez even boiled over into a bizarre abortive coup against Chávez that saw the president ousted for 48 hr and then restored to power in April 2002. Ultimately, the opposition's frustration over the coup's failure led it to focus on paralyzing the nation's economy in order to force him from office. And that meant shutting down the oil industry.

The shutdown of oil operations for several months contributed to oil supply shortages in the first half of the year that have helped sustain benchmark US oil prices near $30/bbl for much of this year. But the result was devastating to Venezuela. The strike paralyzed the nation and erupted in sporadic violence that left scores dead or injured. Exports of crude and refined products disappeared, and local fuel supplies dwindled to a trickle. Losses to Venezuela's economy have been estimated as high as $16 billion.

Since then, PDVSA has struggled to return operations to normal. There has been substantive progress in restoring production, exports, and refining operations, although there remains disagreement over to what degree that has occurred.

PDVSA now contends that while its plans for growth have been curtailed from what they were before Chávez came to power, the state company asserts that its current targets are better aligned with what a state oil company's goals should be: an instrument of the state dedicated to the betterment of its people.

In the meantime, however, line managers expressed in private interviews with OGJ concerns about the strains of continuing to operate such a massive enterprise with inadequate staffing for perhaps several more years to come. And tensions continue to simmer within the company's ranks, especially between those strikers who walked off the job temporarily only to return before the ax fell and those who remained behind.

Yet those line managers also say they foresee benefits accruing from operating a leaner, more streamlined operation than the organization it had been— one they claim was bloated by excessively large middle-management ranks for years.

At the same time, PDVSA's leadership acknowledges that it is taking on an increasing burden of direct financial support for local communities and subsidy for local consumption of its products. That will further strain a company already stretched thin by job losses.

That outlook sets the stage for what may prove to be a fresh opening of opportunities for foreign investment in the hydrocarbon-rich nation—assuming political stability returns fully. With PDVSA having reined in its expansive growth plans from the pre-Chávez days, and with demand expected to grow for its crude and products—especially from the US, its No. 1 customer—it may prove impossible for Venezuela to meet that expected future demand without a greater influx of foreign participation in its oil and gas sector.

Indeed, Venezuela now is aggressively touting its prospectiveness for oil and gas investment by foreign companies as it seeks to restore confidence in its stability. Ironically, the same Chávez agenda that led to a huge contraction of one of the world's preeminent state oil companies also spurred a flight of foreign capital from the country before the political turmoil had engulfed its oil sector. Foreign multinational operating and service companies in many instances have reduced their presence there, a process that was under way before this year's civil strife began. And Venezuela's standing as a prospect for oil sector investment has fallen significantly; but that too represents an acceleration of a decline that had begun before Chávez took power, one that began with the disappointing results from the apertura initiative of the 1990s.

Multinational oil companies each assess political risk differently, but all recognize the necessity of that assessment. They continue to operate in many areas of the world that are subject to political turmoil, civil unrest, and even war and terrorism. In most instances, they can live with a certain amount of political risk, as long as they can find a way to calculate that risk. But when a high degree of uncertainty exists as to how political risk can be assessed in a country, investment interest in that nation isn't likely live up to its degree of hydrocarbon prospectivity.

Fresh turmoil ahead?

That's the dilemma Venezuela faces now. A fresh round of turmoil looms early next year with a renewed effort to hold a recall referendum election in the first quarter. (Venezuela's 1999 constitution allows such a recall referendum at the midpoint of a president's 6-year term, which was the case with Chávez as of last August.) Opposition leaders claim to have gathered over 3.6 million signatures on a referendum petition, a third more than needed and an amount greater than the number of votes Chávez received in the 1998 election that brought him to power. Although Chávez denounced the effort as rife with fraud, the Carter Center and the Organization of American States monitored and endorsed the petition drive as legitimate. Venezuela's National Electoral Council will decide, probably shortly after the first of the year, whether enough signatures are validated to hold the referendum. It it does, the next step would be the recall referendum election, to be held probably in February or March.

But Chàvez retains a strong bulwark of support in Venezuela, especially among the 70% of Venezuelans that live in poverty. And his track record—a failed coup against the government in the 1992, violent attacks against the strikers—suggests he will not go peacefully even if recalled. Continued turmoil in 2004 will ensure the uncertainty quotient of assessing Venezuela's political risk will remain high. At the same time, foreign companies have voiced concern about what they contend are fresh uncertainties and fiscal disincentives in Venezuela's new Hydrocarbon Law. And both concerns will have a direct impact on how much capital foreign companies will be willing to commit to its oil and gas sector.

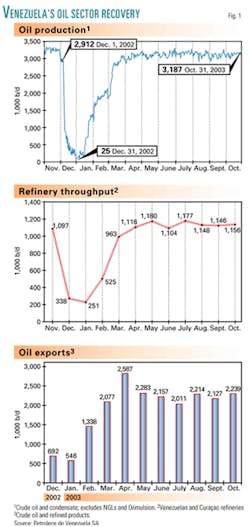

So even if PDVSA's operations have fully recovered, its ability to commit capital needed to expand production to levels needed in the future probably will remain constrained for the foreseeable future, thanks to a growing portfolio of domestic subsidy and direct community support. Its current 5-year business plan calls for outlays of $43 billion for 2003-08 (the 2004-09 business plan was expected to be unveiled by yearend), with private investment accounting for 46%. Such an outlook suggests that even an aggressive public relations campaign by PDVSA's leadership to encourage investment in the country's oil and gas sector won't be enough to achieve the company's goals.

It suggests that foreign investors will seek—and probably win—some improvements in fiscal and other incentives before committing more capital to Venezuela's highly prospective but troubled oil and gas sector.

PDVSA's initiatives

After a prolonged period of offering little other than assertions of production, export, and refining levels that differed sharply with outside perceptions, PDVSA in recent months has embarked on an aggressive campaign to reassure the world's business and financial communities that business is back to normal.

Such initiatives included:

- Conferences and nondeal road shows in key oil centers such as Houston, London, Aberdeen, and Caracas and other oil centers and in financial strongholds such as New York, Boston, and Paris.

- A visit by top PDVSA executives and officials of Venezuela's Mines and Energy Ministry to Washington, DC, to meet with government, media, corporate, and financial representatives.

- Securing improved ratings from the principal US credit ratings agencies.

- Submission of relevant financial statements to the US Securities and Exchange Commission—albeit late because of the disruptions early in the year.

- Payment by PDVSA affiliate PDV America of the last tranche of a $1 billion 1993 bond issue, completing all of the affiliate's debt commitments. Counting its PDVSA Finance affiliate's obligations, the company had paid $1.8 billion of its debt up to October, with another $425 million payments due by yearend.

- A commitment to strengthen and reinforce the presence of PDVSA affiliate Citgo Petroleum Corp. in the US. (The Tulsa-based Citgo is studying a possible move of its headquarters to Houston and had been rumored to be on the auction block, a rumor the parent now dismisses.)

- A call for two new licensing opportunities by yearend, focusing mainly on gas-prone blocks offshore.

- Invitations to insurance officials and refining experts to conduct safety audits of its giant refining complex on the Paraguana Peninsula. A series of mishaps earlier in the year were cited by opposition leaders as evidence of high-risk operations owing to lack of skilled staff.

- Plans to invite independent engineering consultants to audit and verify its production and reserves claims.

*An invitation to foreign journalists to tour PDVSA operations and interview officials ranging from PDVSA Pres. Alí Rodríguez Araque to various operations and line managers.

Recovery touted

PDVSA officials continue to press a theme not only of recovery but of a company better positioned for the future.

At a breakfast meeting with a group of journalists in November, Rodríguez claimed that the company's recovery had occurred much earlier than has been generally believed.

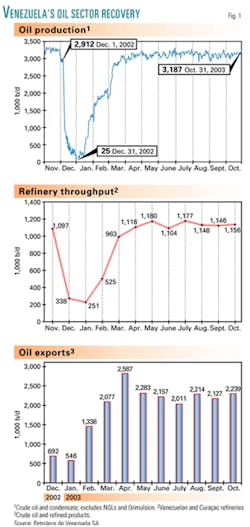

"Despite the attacks on the company, by the end of March, the situation was totally normal," he said. By then, PDVSA claims to have restored oil production to about 3.1 million b/d, a level it says it maintains today. In addition, it says exports of crude oil and refined products had jumped back to about 2.4 million b/d by then, and local refining system throughput (for which PDVSA includes the Isla refinery at Curaçao) had topped 1 million b/d.

Today, opposition leaders claim that Venezuela is producing only 2.6 million b/d, a figure comparable with the level reported for October by the secretariat of the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries. But PDVSA notes that its figure includes extra-heavy crude from the Orinoco belt and natural gas liquids, both excluded from OPEC's quota system and thus not reported to the secretariat. It estimated production of extra-heavy crude, NGLs, and condensate at 360,000 b/d in August. PDVSA last week estimated its exports of crude oil for January-November at an average 2 million b/d.

PDVSA officials also acknowledged that, early in the recovery process, production was occasionally overstated as a result of "miscommunication" between field personnel and company spokesmen.

Irrespective of which numbers are valid, even the opposition's current estimate is a far cry from yearend 2002, when oil production had plummeted to 25,000 b/d (Fig. 1), exports had disappeared, and refinery throughput (solely at the Puerto La Cruz refinery in eastern Venezuela) had plunged to a low of 70,000 b/d.

"What's most impressive," asserted Rodríguez, "was that this result was obtained after the abandonment of work of 18,000 people, including those who had control of key activities."

He recounted a process of restoration that involved coordination of remaining employees and Venezuelan military forces, buttressed by calling in hundreds of PDVSA retirees and consultants from service companies.

As to the issue of validating Venezuela's production levels, Rodríguez said that the state company soon will hire independent outside auditors to begin certifying its production month by month—probably beginning in first quarter 2004. In addition, the government has approved the creation of a new committee within the Ministry of Mines and Energy to certify, on a monthly basis, Venezuelan oil production and prices received for that production.

Rodríguez found some irony in the opposition's claims that the state company is producing far less than it claims.

"Until last year, Venezuela was accused of producing too much under its [OPEC] quota; now it is accused of producing too little," he said.

Struggles described

During a November press tour of Venezuela's operations in eastern and western producing areas and of the Paraguana Refining Complex (PRC), various managers recounted their experiences and progress in PDVSA's recovery from the strike. A number of them in interviews expressed the belief that, despite the strains of managing such vast and complex operations with inadequate staff levels, the company will be better off in the long run without many of the thousands who refused to return to their jobs. In some instances, the anger of those left behind at the strikers was almost palpable: They were occasionally referred to as "saboteurs" instead of as strikers. In fact, there frequent allegations of specific acts of sabotage leveled at strikers or their sympathizers.

Javier Alvarado, assistant manager of PDVSA's western division, cited a recent rise in sabotage incidents and expects security to be stepped up as the recall referendum gains momentum. Field personnel had discovered infield pipelines that had been damaged and electric cables severed.

"The other day, we caught someone red-handed dismantling a wellhead," he said. While the miscreant wasn't a former employee, Alvarado suggested he was hired or otherwise linked to strikers knowledgeable about field operations there.

Alvarado also recounted an instance of having discovered a mini gas plant whose cooling coils had been sawed through when the plant was down for maintenance—again suggesting a saboteur knowledgeable about operations.

Other managers told of damage done by departing strikers—in some instances key managers who allegedly took entire databases with them in order to disrupt operations managers at the PRC, which suffered a loss of 50% of its staff, detailed inadvertent damage to facilities by strikers who apparently believed Chávez would be ousted quickly and thus the strike would be short-lived. (PDVSA's Amuay and Cardón refineries on the Paraguana Peninsula were consolidated into one refinery several years ago, making it the world's largest refining facility at a capacity of 956,000 b/d.)

"When they shut down the refinery, they thought it would be down only a week or soUThey thought operators would be back on the job in a few weeks, so they didn't properly mothball the units," one refinery operator told OGJ. "Keeping it in this mode for months caused damage."

At Cardón, operators found a regenerator full of wet catalyst and a sulfur unit not properly flushed, resulting in line damage. At Amuay, product had solidified in the sulfur unit, causing plugging in the lines and related equipment. Operators at Amuay also found tanks and lines plugged with solidified asphalt and a plugged scrubber at the flexicoker unit.

Contrary to outside perceptions that the PRC has been plagued with operations mishaps because of unskilled operators or undermanned operations, Fernando Padrón, technical supervisor at PRC Amuay, claimed that lost-time incidents since resumption of operations have been "25% less than we had before" the strike. He did acknowledge, however, an Apr. 27 fire at the Amuay desulfurization unit and a recent minor explosion in a basement electrical substation.

PDVSA officials pointed to the certification of safe operations at PRC and Puerto La Cruz refineries by insurer America International Group in March when it decided to continue providing coverage to PDVSA. Still, there are extreme strains on the current operating staff. At PRC, PDVSA is aggressively hiring recent engineering graduates and pairing them with retirees for intensive on-the-job training cycled with equally intensive stretches of classroom study. One such retiree confided to OGJ of 12-14 hr workdays 7 days a week, a regimen he expected to continue for another year or two.

In addition, research programs at Intevep SA, PDVSA's research and development affiliate, were for the most part put on hold as the state company mustered several hundred technical professionals from Intevep to temporarily help fill the void left by striking workers.

But surviving managers in operating units discovered some benefits even amid the strains of understaffing.

"Despite all the problems along the chain," said Padron, the loss of staff represents "a good opportunity to make us more competitive." He noted that losing surplus personnel—citing a redundancy of as much as 100% in maintenance, for example—has helped reduce PRC's operating cost to $1.47/bbl from a prestrike $1.90/bbl.

A similar tale was told at Puerto La Cruz by Alejandro Granado, manager of refining in PDVSA's eastern division.

"In 2001, we did a study that determined that Puerto La Cruz's payroll was deviated 60% from the average seen for [refineries worldwide that were classed] the 'best of the best,' he said. "It was pure redundancyUThe strike allows us to be at that average."

A coddled elite?

The issue of surplus personnel, especially a large cadre of middle managers deemed by some of the PDVSA survivors to be not only superfluous but even a coddled elite, was a sore point in talks with PDVSA operating personnel and line managers.

One point brought up repeatedly was a study done during the tenure of former PDVSA.Pres. Luis Giusti that reportedly concluded there were 12,000 redundant staff at PDVSA.

"But even Giusti couldn't do anything about it," one field operations manager told OGJ. "It was politically impossible to lay off or fire anyone."

Another manager complained of the "very bureaucratic" structure of the old PDVSA organization, citing instances of a 1:1 ratio of managers to workers in some departments.

"It's more efficient now; we have more empowerment now," he said. "Under the old structure, there were 10 levels between us and Caracas; now it's 6, and going down to 4."

The concentration of staff losses in the executive class occurred across the company, say PDVSA officials. In the western operating area, for example, there will be an overall net reduction in staff of 23%. From a level of 13,167 in 2002, the strike left the operating unit's staff at 6,479. Of those, the unionized workforce fell by 36%, technical professional staff dropped by 73%, and executive staff levels plunged by 97%.

Since then 565 have been hired, split 50-50 between professionals with experience (5% of which are retirees serving as short-term employees) and recent engineering graduates. Plans call for hiring another 3,104 to reach an optimum level of 10,144.

Several PDVSA managers told of tense and difficult times for many striking personnel during the 2 months that followed a ultimatum from the PDVSA leadership that the strikers would be considered to have abandoned their posts and forfeited their jobs as of Jan. 15. Although the "deadline" was 60 days past when it was enforced, only a small minority of the strikers returned to their jobs.

"Some of [the strikers] said they thought the government would be ousted and were afraid they would lose their jobs if they worked, and so they stayed home," one PDVSA manager said. "Many now regret having taken the wrong decision."

Other officials claimed harassment and even death threats targeted workers who refused to join the strike.

For Genel Severeyn, Tia Juana district manager in the western operating unit, and his colleagues who remained on the job, the choice was simple: "We are workers, not politicians."

And any prospect of rehiring those who didn't return before the ax fell is out of the question, say PDVSA officials, despite the current strains on the company's workforce.

Citing security concerns related to alleged acts of sabotage by strikers or strike sympathizers, one PDVSA manager asked, "How can you hire someone back who proceeded to act that way?"

Another commented, "Those who claimed abuse of the [PDVSA] meritocracy by politics left on the basis of politics."

Alvarado offered some sympathy for colleagues he contends were led astray by a small group of executives opposed to Chávez. Because of the lucrative compensation packages and perks that came with being executives at PDVSA, he said, some executives were "kind of spoiled by the many entitlementsU some leaders thought there were some privileges they could keep if they kept working in PDVSA."

He pointed to the frequent changes in leadership at PDVSA by Chávez at the outset of his administration as the catalyst for many PDVSA employees to begin the resistance movement that led to his short-lived ouster in April 2002 and later to the strike that began a year ago.

Alvarado detailed his personal reasons for not joining the strike: "I have worked 25 years in PDVSA. I've worked for five governments; I want to work for the next one. I will not stop the company for any political reasonUI believe I should not stop my company.

"That's what I learned from [working at] Exxon [Corp.] and [Royal Dutch/] Shell: You don't stop; if [as an executive] you go outside and you go on strike for 60 days, you're firedU How can an executive go on strike?

"If I feel I don't agree with the owner, I step out, here's my position: Get a replacement for me. Not to use my power as a director to let other staff tell the guys, 'Hey, come with me, because if you don't come with us, when we are back, you are going to be fired—and that happened.

"That's wrong. Because you shouldn't use your power to influence and blackmailUyour employeesUand now they are selling cheese and doughnuts in the street, and I say to them, 'Go and ask them, those directors, where is my job?'"

Social commitments

Alvarado also spoke of how PDVSA is realigning itself more with the bulk of Venezuelan society, moving more to pick up direct funding and involvement in community services—effectively working as more of an arm of the government in social services.

Among such efforts are recent educational outreach programs to boost adult literacy and completion of high school education, programs to make PDVSA corporate medical clinics available to local communities on weekends, and development of new outside support services to create more jobs.

"In Venezuela, I'm sure that you know that the oil industry is one of the state-owned bodies that has efficiency, that can do things," Alvarado said. "You hand out some job to the PDVSA staff, and we're going to work.

"So I say why don't we look outside the fence and see where all those communities are that live for the oil and industry and work for the oil industry in servicesUWhy don't weUdevelop their schools, their streets, and whatever."

'Renationalization'

The opposition has posited that such changes at PDVSA amount to an effective "renationalization" of a state company that had been reshaping itself along traditional business lines to compete with the world's privately owned supermajors and that was widely viewed as drifting away from state control.

Rodríguez's comments regarding changes at the company did little to dispel that notion.

Now, "PDVSA is aligned with the national strategic objectives," he said. "In the past, PDVSA faced a contradiction between the plans and strategies of PDVSA and the plans and strategies of the state. In the past, the company was aligned with other interests than those of the state."

As an example of the latter, Rodríguez cited the apertura program started during the tenure of Giusti (who resigned shortly before Chávez took office in 1999, after PDVSA's leadership was the target of the latter's scathing campaign rhetoric).

"Under the apertura, this program reduced abruptly the fiscal contribution to the state and affected negatively the costs to PDVSA," he said. "Our new plan calls for us to reduce the costs to PDVSA and to increase our fiscal contribution to the state."

He also sought to counter claims that the new regime has created a less favorable climate for investment in Venezuela's oil sector.

"Without any kind of doubt, oil is a business," he said. "UFor an investor, less than a 15% internal rate of return [IRR] is not good business. For Venezuela, less than a 30% royalty is not a good business opportunity. And this was very clear at the time under the Hydrocarbon Law."

While the old Hydrocarbon Law allowed for special circumstances in which the royalty could be reduced to 16.7%, under the apertura program, Rodríguez contends, "this article was clearly violated."

He cited instances where a predecessor leadership PDVSA "flexibilized" the royalty scheme in order to improve a foreign investor's IRR.

"If an investor's [IRR] was 20%, the royalty would be 16.7%; but if [the IRR] was less than 20%, the royalty was reduced progressively. If the [IRR] was 12%, the royalty would be only 1%."

Because of such arrangements, Rodríguez contends, "that means the state sacrificed its share of the business in order to give more and more revenues to foreign investor. That is not good business."

Under the new Hydrocarbon Law, oil royalties are set at 30%, but income taxes have been reduced to 50% from 67.7%, he pointed out, adding, "The state wants to maintain the fiscal pressure on the investor, not to increase it."

In the case of natural gas exploration and production investments, the royalty is set at 20%, and income tax at 35%.

Rodríguez also pointed to concerns within OPEC that accelerating competition among those oil-exporting nations to attract foreign investment could undercut the group's own recent success at soldarity on calibrating production to support oil prices. (The PDVSA president previously served as OPEC secretary-general, where he sought to establish a common royalty rate floor of 20% among members.)

"Some countries now are competing by investment andUreducing the contribution to their populations," he said. "But if you reduce the royalty to 1%, the ability of the state to serve the demands of the population in a very poor country" is compromised. "It is the right of a nation to control our natural resources and to obtain a contribution for access to our natural resources."

He contends that Venezuela's 30% royalty compares favorably to the level of state takes, including severance taxes and royalties, of Alaska, Louisiana, Texas, and Alberta.

Business plans

PDVSA's current 5-year plan entails total outlays of $43 billion, with exploration and production accounting for $29 billion (Fig. 2). The emphasis of the new business plan will be on exploration for light and medium crudes in traditional producing areas, increased monetization of heavy oil resources, an aggressive program for gas development, and "enhancement" of PDVSA's refining and petrochemical businesses.

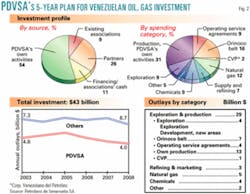

In specific terms, PDVSA's current 5 year plan calls for it to boost oil production capacity to 5.1 million b/d by 2008 from what it claims as 3.7 million b/d today. The biggest increment is expected to come from PDVSA's own production increases and from new discoveries (Fig. 3).

That compares with plans under Giusti to boost productive capacity to 6.2 million b/d by 2005.

Rodríguez described PDVSA's new business plan as a strategy to add value to the country's hydrocarbon resources.

He said that the first requirement of the new Hydrocarbon Law's Article 20 calls for PDVSA to separate its downstream and upstream operations in order to establish greater transparency of operations.

The second requirement is for the state company "to define the value of each barrel we are producing in the different areas" of the country and then to improve productivity and reduce the costs in each area.

Third, PDVSA is to accelerate efforts to better delineate reservoir characteristics and crude qualities in its fields. Rodriguez noted that PDVSA's earlier buying spree for refining capacity abroad left the company in the position of owning a lot of capacity in refineries that could not take its crudes, thus forcing it to buy crude from other countries.

"In this way we are adding to the value oil in other countries."

That brought up the question of the often-rumored possible sale of some of the companies' refining interests, notably the Lemont, Ill., refinery, which doesn't run Venezuelan crude.

Without specifying which, if any PDVSA refining interests were for sale, Rodríguez said, "Possibly we will make some decisions on different refineries in order to align our system with the objectiveU to add value to our natural resources."

Opportunities

PDVSA officials touted an array of new opportunities for investment that will be opening up for foreign investment under the new regime.

One official claimed that three of the operators of the four integrated heavy oil projects in the Orinoco oil belt have approached PDVSA to discuss possible expansions of the projects, with the fourth likely to follow suit soon.

Meantime, PDVSA has begun to implement its latest offerings of exploration and production license opportunities. Currently under way is an E&P license initiative in the Deltana Plataforma area off Venezuela's far eastern coast, a 3,000 sq km believed to contain giant gas-prone structures. The second offering in the Deltana Plataforma area focuses on Blocks 3 and 5, for which eight multinational companies were invited to participate. Earlier this year, PDVSA selected ChevronTexaco Corp. and Statoil ASA to operate Blocks 2 and 4, respectively, in the Plataforma Deltana area (OGJ Online, Feb. 10, 2003).

Venezuela is considering committing some Plataform Deltana gas to Trinidad and Tobago's Atlantic LNG export project, currently mulling a fifth LNG train. Meantime, PDVSA is pursuing its own LNG export project, dubbed Mariscal Sucre, involving gas fields in the Gulf of Paria, in concert with several multinational companies.

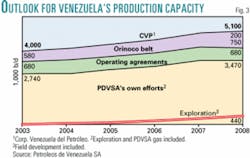

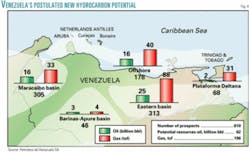

Originally scheduled to begin by yearend is a license offering covering seven blocks in the Gulf of Venezuela and in Falcon state, also believed to be largely gas-prone. These offerings only scratch the surface of an untapped exploration potential that PDVSA believes could yield another 62 billion bbl of oil and 196 tcf of gas (Fig. 4).

Lingering concerns

Despite PDVSA's aggressive efforts to restore the outside world's confidence in the state company and in Venezuela's oil and gas sector overall, there remain lingering concerns.

First and foremost is the recall referendum election, certain to be another nasty political spat that could bubble over into something worse. Chávez earlier this month demanded that the successful petition to seek the recall referendum be thrown out, claiming hundreds of thousands of fraudulent signatures, and later threatening not to recognize the petition even if the National Elections Council endorses it. Another year of political turmoil could ensue, with only wild guesses as to the outcome.

But a Chávez ouster could mean more turmoil at PDVSA. The opposition routinely criticizes the company as "rapidly deteriorating" under Chávez proteges and claims it is overrun with political functionaries whose primary function is to put remaining employees through political litmus tests.

Given the tone of such rhetoric and the antipathy many of the current PDVSA employees exhibit toward the former PDVSA employees, the atmosphere has become so charged that a reversal of fortune for Chávez also could spell a fresh round of bloodletting at PDVSA.

Should Chávez survive politically, there still remain concerns about Venezuela's fiscal solvency, especially following the devastating impacts of the strike. The Central Bank of Venezuela has estimated that the country's economy will contract by 12-15% this year. Some Venezuelan economists project that the country's economy will shrink by 6-8% in 2004.

And some multinationals continue to grumble about the changes in fiscal terms under the new Hydrocarbon Law as well as the law's limit of a 49% stake for private investors in any upstream project.

By most measures, PDVSA has made a remarkable recovery. And Venezuela's conventional hydrocarbon potential is unmatched in the Western Hemisphere.

But almost any scenario includes difficult shoals for PDVSA and Venezuela to navigate in the next year or so, with a growing possibility that more outside capital will be needed to meet even PDVSA's currently more modest production growth goals.

Meanwhile, demand for OPEC crude is widely expected to increase in the coming decade. And the US, Venezuela's chief customer, is looking increasingly to Russia, the Caspian Sea region, and West Africa as attractive alternatives to the volatile Persian Gulf region.

It all could add up increasing pressure on PDVSA to pursue more competitive terms or relinquish more control to foreign investors in order to keep up.