E&P asset/portfolio risk analysis: Addressing a many-faceted problem

E&P RISK ANALYSIS—1

The publicly quoted upstream oil and gas sector suffers from disappointing long-term returns and growth from capital invested in drilling. Results continuously fall short of "risked" return targets of 10-15% employed by much of the industry.

A key reason for this is a general failure of the exploration and production (E&P) industry, operating companies as well as industry analysts, to adequately account for all aspects of risk. The industry has no standard method for assessing and adjusting for risk.

Disagreement is widespread over what constitutes a comprehensive risk assessment and adjustment scheme. This results in inconsistencies and omissions when applying risk assessment schemes to individual assets or portfolios of assets.

Perceptions vary over what constitutes risk (opportunity for loss) and uncertainty and the need to manage and mitigate risks without compromising opportunities for gain. This inconsistency needs to change if companies are to improve their forecasting and credibility with investors and other stakeholders.

Risk is a many-faceted phenomenon requiring a range of assessment techniques to yield a systematic and quantifiable analysis that can be used to adjust (i.e., risk-weight) project, portfolio, and corporate cash flow analyses in meaningful ways.

Even the most sophisticated and comprehensive risk analysis techniques will only approximate to the "right" risk adjustment factor and will not account for all eventualities.

Some managers wonder why they should bother. Many would agree that all economic evaluation models more often than not provide the "wrong" answer. They justify using the models, however, on the basis that some models provide more useful insights than others and represent the best available tools to aid decisionmaking.

The same assessment applies to risk analysis, which requires rigorous and systematic analysis to optimize companies' understandings of corporate risk exposure. Of course, risk analysis should not only focus on the downside but also include balanced assessments of opportunities that might be exploited in conditions of uncertainty.

Some financial analysts would argue that the impacts of most upstream risks can be minimized best by simple diversification.

While diversification helps spread the risk and reduce the impact on company and portfolio performance of individual project failures, unlike the theoretical situation for financial instruments, diversification does not eliminate or reduce the impact of the tangible risks within individual projects, which, if they are to perform to full potential, still require management and mitigation of the opportunity for loss.

Diversification alone is not a sufficient risk management strategy for E&P asset portfolios. More proactive portfolio management methods potentially improve performances, but they rely upon quantified risk assessments of the individual assets.

Modern portfolio modeling and management systems provide great benefits to oil and gas companies by integrating economic and risk analysis at the asset and portfolio level with corporate strategy.

Fig. 1 illustrates how portfolio models can help to evaluate and optimize E&P assets and frame investment decisions and options. However, for such models to be meaningful, portfolio managers and analysts must not lose sight of the individual assets and the specific risks and opportunities associated with them. It is essential to perform risk analysis at the asset and portfolio levels, and that analysis should ideally be holistic, taking into account the many facets of risk and building options and cases into the valuation models to exploit identified opportunities.

In the upstream sector, risks can be broadly divided into subsurface and operational categories. The operational risks can be further divided into project and commercial categories, which can be further subdivided.

Table 1 illustrates one integrated and holistic E&P risk analysis scheme that assesses 12 distinct components of each E&P asset with equal weight and assumes that each component is independent. This assumption of independence justifies application of the multiplication rule to calculate combined probabilities. Other schemes may choose to subjectively apply unequal weights to the components assessed according to their deemed importance.

The assumption of independence seems well founded for most subsurface risks, i.e., the presence of a reservoir, a trap, or a source rock are geologically independent within most geological environments.

However, even between these technical attributes there are subtle dependencies. For example, the ability of a reservoir to flow at commercial rates is often dependent on reservoir continuity and trap geometry.

Similarly, the quality of the petroleum in the reservoir is linked to the quality and type of source rock, fluid migration history, depth of the trap, and interactions of petroleum fluids in the reservoir with other subsurface fluid movements.

For the project and commercial risk categories dependencies are more complex. Political bureaucracy may influence the risk of completing a project on time. Moreover, fiscal and business risks are intimately entwined and dependent upon some political risks.

The assumption of independence is therefore a simplification of a more complex overall interaction of the different facets of risk that affect E&P projects. However, it does provide a method for rigorous and systematic assessment.

Subsurface risk analysis

Companies that desire to maintain competitive advantages rarely disclose their risk assessments of subsurface categories, which geoscientists and engineers usually analyze and quantify on a probabilistic basis project by project. Hence third-party analysts without access to the data are unable to evaluate the assessments.

A common approach adopted for exploration projects is to assess in probabilistic terms the chance of several independent oil and gas prerequisites being present in the prospect in question (e.g., source rock, reservoir, and trap) and then multiplying the probability of each prerequisite together to provide an overall subsurface risk adjustment factor or chance of success.

Table 1 shows a typical 6-point subsurface risk analysis scheme. Some companies use 3-point or 4-point schemes. In fact, it is good technical practice to routinely evaluate a larger number of technical attributes prior to assigning probabilities to specific subsurface risk-assessment categories.

Fig. 2 shows a 12-point subsurface evaluation scheme that could be used as an aid to applying probabilities to the 6-point scheme illustrated in Table 1.

Many geologists and engineers might wish to expand the technical risk assessment matrix to include further subsurface attributes. In the qualitative assessment process there is no problem with doing this, but for a meaningful probabilistic scheme ultimately all the attributes considered have to be synthesized into a limited number of technical categories to calculate an overall subsurface risk-adjustment factor.

Discounted cash flow forecasts for E&P prospects, incorporating reserves, production rates, costs, and oil and gas price forecasts, based upon specific fiscal terms for the jurisdiction in question, can be adjusted or risk-weighted with the overall subsurface risk adjustment factor calculated. This expected monetary value (EMV) approach is the method adopted by many companies to express the risked values of their projects.

This approach is fine as far as it goes, but many companies then go on to assume that such analysis incorporates all facets of risk associated with the projects, failing to incorporate the multitude of operational risks that also affect the success of the project.

For rank wildcat wells, historical worldwide drilling results indicate that approximately 9 out of 10 are commercial failures (dry holes or noncommercial discoveries). The risk-adjustment techniques should clearly reflect this.

On the other hand, exploration prospects in more mature oil and gas basins (trend wildcats) have recently had their chances of success improved by high-resolution 3D seismic techniques to an approximate range of 20-50%.

Few in the industry take seriously claims made recently by some companies of being able to eliminate exploration risk by "exploring with seismic and appraising with the bit;" they prefer to believe the empirical observations that all major companies continue to drill a substantial number of dry holes when testing their exploration prospects.

Once oil is found, many but not all of the subsurface risks are removed (e.g., the presence of a source rock, reservoir, and trap are confirmed by a discovery). However, a myriad of operational risks associated with developing the discovery and translating the production into operating cash flow then come into play, often with a vengeance.

The subsurface risks that remain with field development projects reduce the chance of achieving commercial production targets to 50-90%, depending upon the reservoir complexities of the field (e.g., small-scale heterogeneities, faults, fractures, and water movements that lie beyond seismic resolution).

Infill development wells are likely to be less risky than step-out wells. The subsurface risking scheme employed should reflect such reservoir and trap performance uncertainties.

Operational risk analysis

Project risks

These encompass most of the operational risks that the company can, through efficient project management, influence or mitigate. Hence it is not unusual for such risks to be reduced as projects move through the planning, sanctioning, and implementation stages.

The three subcategories identified in the integrated E&P risk analysis scheme illustrated in Table 1 and assessed are:

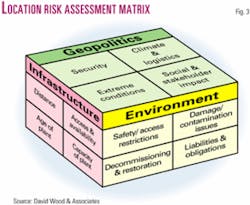

Location: This identifies risks associated with remote and frontier surface locations (e.g., polar, deepwater, mountainous, harsh climatic areas, etc.), environmentally sensitive access, entry restrictions to existing infrastructure or lack of infrastructure, obstacles to delivery to domestic or export markets, elevated chances for accidents, environmental damage, decommissioning costs, community reaction, and intense public attention. A 12-point location risk assessment matrix is illustrated in Fig. 3.

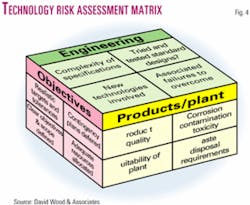

Technological: This addresses the reliability and complexity of the technology and plant on which cash flow from an asset depends. Questions for assessment include:

Are new, essentially untried technologies required to achieve field development?

Is the engineering complex, requiring innovative solutions and unusual components, or is it based on standardized designs?

Are drilling conditions difficult or benign, and are there tight or broad limits on target objectives?

Do the reservoir fluids contain toxic or corrosive components that require extra processing or could lead to contamination, decommissioning, and environmental cleanup issues?

Are production facilities and other infrastructure old, dilapidated, or subject to excessive downtime, due to equipment problems or working practices?

A 12-point technology risk-assessment matrix is illustrated in Fig. 4.

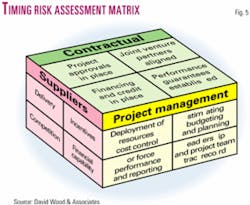

Timing: This evaluates operational and contractual issues that might cause major delays in field development, such as planning approvals, financing and liquidity risks, project management practices, contract structures, incentives and remuneration with key suppliers and service companies, labor union disputes, community protests, and track records of similar projects in the region.

Project cost risks are not assessed here as uncertainties in costs are generally built directly into the project cash flow analysis as probabilistic input distributions to simulation models. A 12-point timing risk-assessment matrix is illustrated in Fig. 5.

Project management practices to deliver an oil or gas field development within budget and on schedule would incorporate a detailed analysis of all project risks and develop mitigation strategies.

The more superficial analysis proposed here is for the purposes of assessing the overall risk exposure of an oil and gas prospect or field at a given point in time. It is not intended to replace that more detailed risk-assessment and cost-time simulation required as part of prudent project management.1

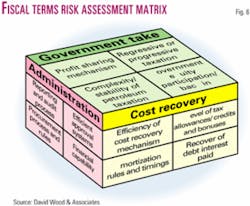

Commercial risks

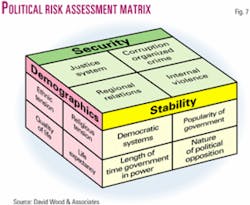

These encompass political, business, and fiscal risks, which warrant individual assessment. Figs. 6, 7, and 8 show matrices of interrelated issues important to the success of oil and gas projects.

Different companies and analysts will consider some of the attributes more important than others, and some will probably include some criteria not identified in the matrices. The matrices are designed to provide a guide to the range of commercial risks that can affect E&P projects and require analysis in a comprehensive risk-assessment scheme.

If the risk-assessment scheme is to be used to risk-adjust discounted cash flow models that have been structured to incorporate fiscal terms (tax rates, royalties, etc.), then the fiscal risk-assessment process should not also assess the economic performance of the fiscal system. If it does, then the cash flow calculation will be "adjusted" twice for economic performance of the fiscal terms. The fiscal risks are those associated with fiscal uncertainty—part of which is the risk of increased taxation such as in the UK in 2002.

There are many interactions and dependencies between the business and political risk-assessment attributes identified in Figs. 7 and 8. These are often the most subjective categories to assess.

Meaningful assessment requires detailed local understanding of a country and an eye for susceptibility or exposure of a country to regional and global risks.

Some organizations market regular reviews of political risk for most countries from a general perspective, which offers a useful starting point for such analysis. However, more specific analysis focused on the oil and gas industry is essential if the assessment is to be comprehensive and relevant to oil and gas projects. It is possible for countries to have specific risks or advantages for the oil and gas industry, which may not be identified in the more general proprietary political risk analysis on the market.

Next: Project maturity versus uncertainty and risk exposure.