Take-or-pay gas supplies may swamp Turkey's demand

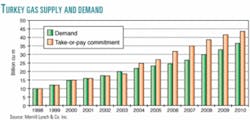

While it may have alleviated its oversupply problems for 2003, Turkey's take-or-pay contracts for natural gas are likely to outstrip its projected demand by 20% in 2006, said analysts at Merrill Lynch & Co. Inc.

The mismatch between Turkey's market for natural gas and its growing contractual supplies "looks to reach disproportionate levels from 2004," said Merrill Lynch analysts in a July 21 report. They project a take-or-pay surplus "of some 1-3 billion cu m over the next couple of years," growing to as much as 8 billion cu m in 2006-08.

"Without a recovery in demand, the pressure remains on Botas [Turkey's state pipeline company] either to seek to renegotiate the terms of contractual deliveries over the medium term or to divert supplies to third-party corporate or country buyers," the analysts said.

Renegotiating contracts

Turkey's government "successfully renegotiated every supply contract to some extent" for 2003, "allowing so much flexibility that demand is likely to run ahead of the temporary take-or-pay levels," said Merrill Lynch analysts. However, they said, "Suppliers are strongly resisting attempts by the Turkish government to renegotiate contract terms over the longer term."

They noted recent reports in the Turkish newspaper Hurriyet that the Royal Dutch/Shell Group is negotiating with Turkish government officials to buy Turkey's LNG supply contracts with Algeria and Nigeria. Shell "is presumably willing to bet on its trading capabilities in LNG and looks to place the gas in western European (or even US) gas markets," Merrill Lynch reported. "The company's position as the main private stakeholder in Nigeria LNG may help in getting the contract's destination clauses revoked."

All of Turkey's gas supply contracts "are thought to contain destination clauses," said analysts. But if those restrictions can be lifted by agreement with the seller, they said, "Botas may gain the flexibility to sell the gas on to third parties."

Merrill Lynch also noted a February agreement between Turkey and Greece to build between those countries a pipeline with an annual capacity of 500 million cu m, "potentially enabling Iranian gas to be sold into northern Greece. The sums involved are small, although we expect the pipeline to be built to considerably higher capacity, allowing Turkey to potentially access the Black Sea states [Romania, Bulgaria, and former Yugoslavia] that currently rely almost exclusively on Russian gas."

The Bluestream deal

So far, Turkey's primary emphasis has been on renegotiating Russian gas supplies through the recently commissioned Bluestream ultradeepwater pipeline across the Black Sea (OJG, Nov. 20, 2000, p. 78).

Bluestream is a 50:50 joint venture of ENI SPA of Italy and OAO Gazprom of Russia, designed to link the gas distribution network of the Krasnodar region in southern Russia to the central Turkish grid at its capital city of Ankara via a 2,150 km pipeline. "The gas sales agreement between the Bluestream partners and Botas ultimately calls for the sale of 16 billion cu m/year of gas," said Merrill Lynch analysts.

"Although Bluestream agreed to lower volumes for 2003, this was primarily a result of a technical delay on the Russian side of the line," they reported. "The line is now ready to deliver gas, and the owners are still holding out for Botas taking its contractual obligation, once the take-or-pay clause [goes] into force towards the end of August. Botas, however, seems ready to dispute the contract terms and may seek to push for a full arbitration."

The analysts said, "This dispute seems to reflect what we believe is a massive pricing premium that Bluestream gas enjoys in the Turkish market—a price that was needed to justify the huge costs of building the pipeline across the depths of the Black Sea. We estimate the border price of Bluestream gas at around $3.25/MMbtu, whereas the landed price of Iranian gas is put at around one third of that."

There's an additional transportation charge to get Iranian gas to Turkey's key markets. But even with the recent decision by the Energy Market Regulatory Authority to regulate Botas' pipeline tariff at 40¢/MMbtu, Iranian gas remains "the cheapest in the market," the analysts said.

Botas enjoys some leverage in renegotiating legally binding take-or-pay contracts, since Turkey eventually will become a key regional hub for new gas supplies into Western Europe. "For Iran, there is virtually no way to access future European markets without going through Turkey," said Merrill Lynch analysts. "For Russia, Turkey represents an important alternative access route to Europe, offsetting its current reliance on Ukraine as a transit. It is undoubtedly in the interests of both countries to at least consider near-term contract renegotiation, rather than risk long term damage to their future gas supply growth."

Shah Deniz gas

Another target for potential renegotiation of price and volume, said the analysts, is the natural gas purchase agreement that Botas signed in 2001 with the development partners for giant Shah Deniz field in Azerbaijan. That deal calls for gas to be supplied to Turkey at an initial rate of 2 billion cu m/year, starting in 2006, and increasing to a maximum 6.6 billion cu m/year by 2009.

Partners in the Shah Deniz consortium approved first-phase development plans for that project in February, with a "likely" total investment of $3.2 billion (OGJ Online, Mar. 10, 2003). That includes $2.3 billion for upstream operations and $900 million for midstream investments, including a gas export line to Turkey.

Partners in the Shah Deniz consortium include BP PLC, operator, 25.5%, Statoil ASA 25.5%, State Oil Co. of the Azerbaijan Republic, Total SA, Naftiran Intertrade Co. Ltd., and LukAgip NV—each with 10%—and Turkiye Petrolleri Anonim Ortakligi 9%.

"Statoil has by far the greatest relative volume exposure to this project among the European partners, perhaps explaining why the company has been so keen to take a leading role in the gas sales and pipeline elements of the project," said Merrill Lynch analysts.

Turkey's market changes

In the mid-1990s when Turkey's demand for electricity was growing at 12% annually, the country embarked on an aggressive program to lock in new natural gas supplies from Russia, Iran, and Nigeria to fuel that growth. "Power shortages were common in the country prior to [its] 1999 economic collapse, a problem that was compounded by a severe drought, reducing hydroelectric output. The government sought to promote newbuild power generation capacity, both government-sponsored and IPP [independent power plants]," Merrill Lynch reported.

However, a major earthquake on Aug. 17, 1999, and the subsequent collapse of the country's economy derailed Turkey's growing demand for energy. The earthquake, with a Richter magnitude of 7.4, was the largest on record to have devastated a modern, industrialized area since the 1906 San Francisco and the 1923 Tokyo earthquakes. Its epicenter was 7 miles southeast of Izmit, an industrial city about 56 miles east of Istanbul, and was felt over a large area, as far east as Ankara, 200 miles away. Unofficial estimates put the death toll at 30,000-40,000.

Residential and industrial demand for natural gas "actually contracted" as a result of "lower economic output and the physical impact of earthquake damage in the northwest industrial region of Kocaeli. In addition, a lack of available capital saw Botas pull back from plans to expand the distribution network outside of the four main cities," said analysts.

Botas earlier established a gas grid in the four largest Turkish cities—Istanbul, Ankara, Bursa, and Eskiesehir—where 20% of the country's population is concentrated, analysts said.

"The somewhat inevitable result of rapidly growing supply at a time of economic malaise is that Turkey has been left with a substantial [and growing] surplus of contracted gas," they reported. "Our estimates suggest that the country could be up to 9-13% over-supplied in the next 2-3 years, a level that could balloon out to 20% oversupply before the end of the decade."

Turkey is Europe's seventh largest consumer of natural gas, representing 5% of the European Union's total gas consumption. Natural gas accounts for 23% of Turkey's energy mix, compared with the European average of 24%. However, the makeup of Turkey's demand is substantially different from the rest of Europe, with a heavy bias of 67% going to power generation, compared with a European average of 20%, the Merrill Lynch analysts reported.

Turkey's demand for gas remains uncertain for the "near and medium" terms, they said. "There are some signs of economic recovery," the analysts observed. "However, the country's high indebtedness leaves the economic situation somewhat fragile. Assuming that the economy does not take another backward turn, then we believe that gas demand can reassert growth rates in the low double digits."

Still, they said, "Our estimates fall well short of the growth rates that Botas planned upon in the mid-to-late 1990s."

Merrill Lynch officials reported, "It is the likely slowdown in newbuild, gas-fired power generation over the 2004-06 period that is placing the key downward pressure on demand. Yet, it is probable that if economic growth does recover to any real extent, then Turkey runs the risk of mid-1990s type power shortages reemerging towards the end of this decade."

They said, "With the economic uncertainty still very much a reality, we doubt that many new generators will commit to adding capacity unless real fiscal incentives are added to entice the investment dollar."