US midstream standing at yet another critical juncture

At any time, the effectiveness of the US midstream sector to deal with challenges has depended on how well its companies accept certain realities and deal with issues they face.

Currently, the business climate for the midstream sector is uncertain. Enron after-shocks, a sluggish economy, geopolitical events, and high-priced natural gas are only some of the larger issues testing the midstream sector. How midstream businesses react to these and other issues will determine the sector's future.

Gaining a perspective of where the midstream sector might be headed requires a review of its history and past challenges, an examination of its current makeup, and a discussion of the abilities of midstream players to handle what lies ahead. And it will be necessary to ask whether the midstream sector needs realignment.

What is 'midstream'?

The midstream sector is a collection of assets and services that help link supplies with demand for any energy commodity and is only as strong as its ability to link one side of the value chain with the other side.

The sector can include but is not limited to the following functions:

- Gas gathering, treating, and processing.

- Natural gas pipelines (primarily intrastate).

- Product pipelines (mainlines and distribution, or "purity lines").

- Fractionation.

- Natural gas and product storage.

- Product terminals.

- Import and export facilities.

For the present discussion, "midstream" will primarily refer to those functions involved in production, handling, and distribution of NGL.

The midstream NGL value chain is interwoven between the exploration and production sector upstream and the petrochemical, refining, and retail fuel and power markets downstream (Fig. 1) such that the sector is often subject to forces beyond its control. Market events that can affect crude oil, natural gas, petrochemicals, refined products, and even electricity can influence the performance of a midstream business.

Also, midstream has no distinct ownership boundaries. Today, major oil companies, independent oil and gas producers, independent gatherers and processors, intrastate pipeline companies, energy merchants, petrochemical producers, and master limited partnerships have operating or ownership positions along one or more segments of the midstream value chain.

The significance of this point for the sector's ability to handle the challenges will be discussed presently.

How we got here

Before 1980 and unlike today, ownership in midstream was much simpler:

Major oil companies built midstream facilities to bring their equity production to market and to supply their refineries and petrochemical plants.

Interstate pipeline companies moved into gas gathering and processing to expand their rate bases and secure natural gas supplies.

- Even "old line" petrochemical companies built NGL gathering lines, gas pipelines, and fractionation and storage facilities to secure their fuel and feedstock supplies.

During this time, energy markets were heavily regulated. Natural gas was considered a premium fuel, and the long-term availability of natural gas and NGLs was uncertain. The critical problem for these players was securing and controlling hydrocarbon supplies for their downstream facilities and customers.

Owning and operating midstream assets served this purpose, and there was an unwillingness to rationalize capacity or sell marginal midstream assets.

As such, midstream assets functioned more as a utility and less as a profit center. Seldom did these assets serve third parties for companies' fears of becoming federally regulated.

By the 1980s, independent midstream players serving third parties began to make their presence known. Independent gatherers and processors, intrastate pipelines, and NGL logistics companies were expanding, aided by price deregulation and a greater confidence of crude oil and natural gas availability.

- Because their assets were oriented to major producing basins or were located in major market centers, they had a strong regional presence.

- They mostly depended on wholesale markets.

- They operated for profit, serving upstream and downstream customers.

Although independent midstream companies were growing during this period, a number of issues highlighted the vulnerabilities and excesses of the sector:

- "Take-or-pay" contracts strained the relationship between producers and gas pipeline companies.

- Price deregulation brought on margin volatility and competition from alternative fuels and petrochemical feedstocks.

- The gas "bubble" developed, as gas went from supply constrained to demand limited.

- Gas drilling plummeted, NGL production stagnated, and gasoline-lead phasedown and vapor-pressure controls diminished the marketability of natural gasoline and normal butane as motor- gasoline blendstocks.

The conditions of the 1980s gave rise to midstream rationalization and consolidation in the early 1990s.

- Lacking the desire to seek third-party customers, some majors and E&P companies sold their midstream assets as their equity production declined and their focus shifted to bigger offshore or international plays.

- Consolidation also occurred within the midstream sector as independent players began to merge with or acquire other players to create greater economies of scale and scope.

The early 1990s also ushered in the environmental movement.

Natural gas was recognized as a reliable, clean fuel that would play a key role in the nation's clean-air crusade. Price deregulation and the repeal of the Fuel Use Act in 1987 that restricted gas use in new power-generation facilities started to yield dividends as gas demand began to rise.

By the mid-1990s, midstream was a model for extracting opportunities and serving customers and providing a marketing and trading platform in a relatively unregulated environment.

Additionally, midstream could offer returns exceeding the regulated cost-based returns of the utilities and interstate pipelines.

The attractiveness of the midstream sector combined with a growing economy and the advent of power deregulation gave rise to a "feeding frenzy" for midstream companies and assets in the mid to late 1990s.

Electric utilities, diversified energy companies, and energy marketers were the primary acquirers of midstream companies and assets.

During this time, cash flows, as defined by earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization (EBITDA) for many sector participants were peaking. Multiples paid for midstream businesses averaged 10 times the previous 12 months' EBITDA, with a range of 8 to 13 times. This implied a return on investment in the single digits, unless the acquirer could generate significant cost savings or business opportunities.

Some acquirers, new to midstream, failed to recognize the risks or take the necessary steps to succeed in a deregulated market. In many instances, adequate synergies were not generated to support the high multiples paid, which made the acquisition particularly sensitive to normal economic downturns or market shocks.

Upstream and downstream forces were often taken for granted in the belief that the midstream entity could be relatively immune to market pressures.

By 2000, another wave of transactions washed over midstream as some companies left their midstream businesses at a significant discount from their original purchase prices and at reduced multiples of 6 to 8 times EBITDA.

For other diversified energy companies, their midstream acquisitions and joint ventures provided them geographically focused assets with greater access to hydrocarbon resources and markets.

These companies were labeled the "energy super stores" or what is as commonly referred to today as the "energy merchants," entities marketing and trading a host of energy commodities.

Master limited partnerships greatly expanded their presence in the midstream sector during the past several years. These are publicly traded entities managed just like C-corporations but with distinctions:

- MLPs distribute a larger amount of cash flow to their shareholders because net income is taxed only at the shareholder level, thus avoiding the double taxation of dividends common to C-corporations.

- MLP units are valued based on their expected distributions, currently yielding 6% to 8% with expected growth of about 5% to 10%/year. The sanctity of the distribution is important to investors.

Consequently, the most successful MLPs have focused on that portion of the value chain with predictable, consistent cash flows. Many large, diversified natural gas companies and energy merchants have formed MLPs and are their general partners.

Today, a diverse group of companies makes up the midstream sector.

Majors, energy merchants, independent midstream players, and a petrochemical company occupy the top positions along the NGL value chain (Fig. 2).

These and smaller midstream companies make up the sector, as we know it today. Some are more integrated than others, and many have different strategic and financial objectives for being in the midstream business.

The sector continues to transform, however. The aftershocks of Enron have exposed the financial vulnerabilities of some energy merchants operating in the midstream sector. These players are fighting for their financial survival: putting projects on hold and selling assets (many of them midstream) either to their MLP affiliates or to third parties.

Other players and outside investors are taking advantage of this situation by acquiring these midstream assets, while a few industry participants are trying to decide if their midstream holdings are core to their long-term futures.

What we face

In the midst of this turbulence, midstream companies must respond to a number of realities and issues, listed here in no particular order:

- Price and margin volatility.

- US petrochemical industry's health.

- Poor market liquidity for NGLs.

- High-priced gas environment.

- A maturing gas resource base.

- Tight credit.

These issues are not mutually exclusive and often have cause and effect relationships so that each issue cannot be examined in isolation of the others.

A midstream company's ability to deal effectively with these issues depends on its size, corporate structure and financial strength, strategic focus, the type and location of its midstream asset, its integration along the value chain, and its commercial arrangements with customers.

The following discussion covers critical areas in which these issues have the most impact.

- Processing margins ("frac spread"). Price and margin volatility has been a long-standing issue confronting US gas processors since the early days of energy-price deregulation. NGL price volatility exists simply because NGL market values are set by or in competition with the value of petroleum-derived products used in the production of petrochemicals and motor gasoline.

Consequently, the same global market forces and geopolitical events that drive crude oil prices can greatly influence NGL prices.

While product prices determine NGL market values, the price floor for NGL is set by natural gas prices, which are influenced more by North American market fundamentals. At many times, the market cycles for natural gas, crude oil, and petrochemicals move in different directions, either because of weather, economic cycles, industry events, or geopolitical crises.

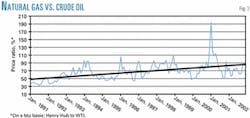

When these happenings occur, the "frac spread," or the margin between NGL and natural gas prices, can change dramatically and frequently (Fig. 3).

Over the past 5 years, the frac spread has averaged around 11¢/gal, below that required to justify a return on investment for a new cryogenic plant processing the average US gas quality of 2 gal/million cu ft (or GPM) gas.

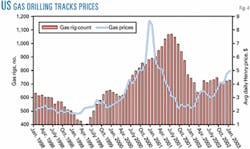

- Natural gas. Concerns are mounting that a fundamental shift is occurring in the North American gas market toward consistently higher prices. Since 2000, US Gulf Coast prices have averaged nearly $4/MMbtu, much higher than the $2/MMbtu average level of the 1990s.

Absolute prices are higher, but more importantly natural gas is becoming more valuable relative to crude oil (Fig. 4). The gas-to-crude price ratio averaged 77% over 1999-2002, compared with 70% over 1995-98 and 51% over 1991-94. As crude prices return to $25-30/bbl, gas prices in the $3.50-4.50/MMbtu range may be normal with more upside pressure than downside.

The days of sub-$3/MMbtu gas are less likely to occur, unless sustained crude prices drop to less than $22/bbl.

Several supply-demand fundamentals are responsible for elevating the value of gas relative to other energy commodities.

On the supply side, concerns are that natural gas production for 2002 declined 2-6% from 2001 production. Although drilling in Canada is nearing records, continued apprehension abounds concerning US gas production, based on the lack of any upturn in domestic drilling activity, despite the rise in gas prices earlier this year to more than $5/MMbtu (Fig. 5). Historically, a rig-count increase has lagged a gas-price increase by at least 6-9 months.

The disconnect between high gas prices and drilling activity indicates a structural change in the E&P industry. As a result, a repeat of the frenzied pace of opportunistic drilling spawned by the 2000-01 price spike is unlikely.

The structural change that could be under way is as follows:

- Lower 48 producing basins are maturing and offer lower rates of returns than in the past with exception of deepwater Gulf of Mexico and coalbed methane in the Rocky Mountains.

- Industry consolidations, particularly among majors, have created "super-large" companies that must pursue prospects that yield longer-term higher rates of return to support their cost structures. Accordingly, many large E&P companies are focusing on less mature international prospects, unconventional gas plays, and deepwater gulf.

- Many other US producers are limited by leveraged balance sheets. Because of tight capital, many medium-to-small players are husbanding their cash or developing what holdings they already have, which are generally older and therefore smaller reservoirs.

While the US is still rich in reserves, it may take a sustained, high-priced gas environment to spur an increase in drilling. Without the majors' strong participation and a slower response by independent producers, the rate of increase in drilling, seen after previous price spikes, may be slower and will probably exacerbate the current supply tightness.

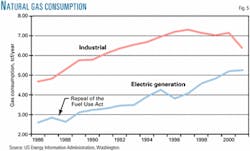

On the demand side, electric-power generation is about to overtake the industrial market as the primary consumer of natural gas in the US (Fig. 6).

Repeal of the Fuel Use Act in 1987, environmental regulations, and a growing appetite for electricity created a favorable environment for independent power producers and nonregulated utility affiliates to build gas-based power generation. These new power plants, still coming online, are more fuel efficient and are displacing older, less efficient utility boilers that had some fuel- switching capabilities.

Consequently, the newer power plants can tolerate higher relative values for natural gas than the older less efficient generators. As natural gas consumption for electric power continues to grow, the economics of power generation will increasingly set the marginal price for natural gas.

This situation threatens the price competitiveness of US manufacturers, steel, paper, and petrochemical producers as well as gas processors, all of whom either use gas as a fuel or feedstock or both.

The implications for the US petrochemical industry and its impact on the midstream sector are covered below.

Petchem dependence

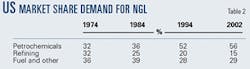

The midstream sector increasingly depends on the US petrochemical industry as a market for NGLs (Table 1).

The US petrochemical industry currently accounts for about 56% of total US NGL demand of around 2.8 million b/d, compared with only 32% of the 2.2 million b/d of NGL consumed nearly 30 years ago.

Its dominant NGL market share is due to the following reasons:

- US ethylene capacity based primarily on ethane and propane cracking doubled over the last 20 years.

- Refinery demand for normal butane and natural gasoline declined because of lead phaseout and vapor-pressure controls.

- Fuel and other uses for NGL grew only moderately.

From the perspective of US ethylene producers, ethane and propane now constitute 65% of their total feedstock supply vs. 50% 20 years ago. The reliability of natural gas and NGL supplies and the fact that it is cheaper to build ethylene plants based on light NGL were mainly responsible for this feedstock shift.

Midstream's relationship with the petrochemical industry goes well beyond market share. Given that the "old line" petrochemical companies were some of the first to enter midstream, the physical ties between the two industries are strong, as shown by the following:

- About 92% of US ethylene capacity is along the Texas-Louisiana Gulf Coast.

- More than 75% of that capacity has direct access to Mont Belvieu.

- More than 90% of total US ethylene capacity connects to at least some part of the US NGL transportation system.

- Almost every ethylene plant has access to underground NGL storage.

Obviously, the US petrochemical industry's health is important to the NGL value chain. A sluggish economy has reduced average operating rates of US ethylene plants to the low 80% levels. The relatively high prices of natural gas and NGL are also causing severe and perhaps long-term competitive damage to the US petrochemical industry, according to the consulting firm CMAI, Houston.

Economic slowdown and higher feedstock and fuel costs are already having an impact, as shown by Dow Chemical Co.'s announcement earlier this year that it would shut down its Seadrift and Texas City, Tex., ethylene plants later this year to reduce expenses. These are primarily ethane crackers consuming a total of 40,000 b/d of ethane, about 6% of the ethane produced by US gas processors.

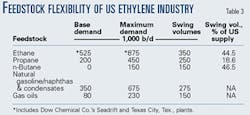

Petrochemical companies with flexible feedstock plants are also reevaluating their long-term feedstock slates and may be looking to reduce ethane cracking. The nation's ethylene producers have considerable flexibility to swing NGL consumption and affect NGL supply-demand balances (Table 2).

The major concern is that over time ethane-based ethylene plants in the Middle East and elsewhere, which have access to cheaper ethane and natural gas supplies, will pressure the US ethylene industry to minimize ethane cracking. If this were to happen, potentially 40% of the ethane produced by gas processors could be displaced, which would significantly change ethane's role as a clearing market for surplus btus.

On the positive side, cracking of heavier NGL could increase as their values are determined more by crude oil than by local natural gas prices and they produce more valuable coproducts.

Implications

The issues just described pose a number of challenges for all midstream participants and for the viability of the sector.

Managing price, margins

Companies with processing operations face considerable challenges in managing economic risks and achieving acceptable rates of return while still serving the producer.

It is virtually impossible to lock-in processing margins for any length of time because of the poor market liquidity for NGL. Long dated or futures markets for NGL are nonexistent. Those gas processors that have "keep whole" provisions in their processing contracts are therefore most susceptible to price and margin volatility.

Today, many of these processors are attempting to change this contractual structure by offering producers more of a fee-based processing arrangement that enables the processor to continue processing a producer's gas during times of very poor margins.

The benefits are twofold:

1. The producer is assured that his gas will be processed to meet pipeline-quality specifications when processing is uneconomical.

2. The processor can smooth out his earnings stream even though he caps his upside during very good times. This second benefit would be particularly important to those midstream companies that would like to place or transfer their processing business into an MLP.

The jury is still out, however, as to whether gas processors will be entirely successful in this endeavor. Competition from other processors may be the major obstacle, particularly along the Gulf Coast where "keep whole" agreements are more common. This contrasts with more isolated areas such as the Rockies, where processors have less competition and more leverage to strike processing arrangements that lessen the risk of price and margin volatility.

The challenge for some processors is to find the right balance with producers that will not overly penalize either party when markets swing out of balance. There is always the risk that some producers, who have enough critical mass, might process their own gas or seek out competing processors who are willing to withstand the volatility of a "keep whole" agreement.

Improving efficiencies

Midstream participants must adjust their operations when ethane cracking is significantly reduced as competition from international ethylene producers intensifies. Processors may need to upgrade their ability to reject or reinject ethane into the gas stream to optimize btu deliveries against pipeline specifications.

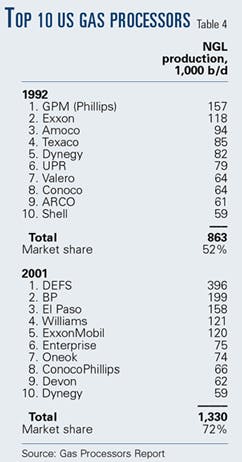

Additionally, the midstream sector must continue to rationalize underused capacity, particularly in gas processing. M&A activity has concentrated 72% of US NGL produced from gas processing in the hands of the top 10 operating companies vs. 52% 10 years ago (Table 3). Another 157 smaller processing companies account for the remaining 28%.

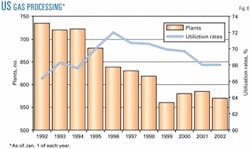

Despite past consolidations among gas processors, the average utilization rate for US gas processing plants has fluctuated between 66% and 72% for the past 10 years (Fig. 7). The low utilization rate is even more concerning given that the number of plants in the US has dropped from 735 to 570 during this period, according to annual surveys of US gas processing by Oil & Gas Journal (OGJ, June 24, 2002, p. 50).

Excess processing capacity continues to be a systemic problem because processing plants are generally captive to a specific production area for their source of gas. Facilities are usually sized for the maximum production that can be reasonably expected. Because a processing plant's useful life can be more than 30 years, production declines can eventually lower the plant's utilization rate during its lifetime.

As major gas-producing basins mature, it will place further pressure on gas processors to rationalize excess plant capacity, lower operating costs, and put greater focus on the growing gas basins that need processing services.

Midstream players that have NGL pipelines, fractionation, and storage facilities must also pay close attention to the dynamics occurring upstream and downstream to be able either to rationalize excesses or adequately plan to bring additional production to market.

The future

Although serious issues face the midstream sector, opportunities along the NGL value chain will continue to exist simply because:

- Natural gas is and will continue to be the clean fuel of choice.

- North American gas reserves are such that producers can find and supply needed natural gas if the economics are right, with Canadian and LNG imports increasingly bridging supply and demand gaps.

- Historically, 80% of all natural gas produced has been processed or conditioned to meet pipeline-quality specifications. There is no reason to believe this ratio will significantly decline. Processing, therefore, will continue to be a "must have" business.

- The US refining and petrochemical industries will remain the largest in the world because of the nation's market size and substantial logistic network, and the majority of the US petrochemical feedstock supply will continue to come from NGLs.

The issues previously discussed, however, will pressure companies with midstream businesses to become more efficient, more focused, and more nimble to generate adequate returns on investment. Rationalization must occur in some segments, margin risks must be mitigated, and links to upstream and downstream forces must be maintained and strengthened.

Revisiting the top NGL players and their situations as 2003 began provides an indication of their ability or position to handle challenges and suggests the direction of the midstream sector:

Duke Energy Field Services (DEFS), a joint venture between Duke Energy (70%) and ConocoPhillips (30%), is heavily concentrated in gas gathering and processing and is the nation's largest operator of gas processing capacity.

- Its core operations are in the Rockies, Midcontinent, Louisiana, Oklahoma, and Texas and offer value-added services such as gathering and processing, transportation, storage, fractionation, and marketing to third parties.

- DEFS is also the general partner of TEPPCO Partners, an MLP that transports and distributes NGL and refined product and has been actively acquiring NGL pipelines and gas gathering systems.

- Through a series of partnerships, the DEFS-TEPPCO combination provides enough critical mass to minimize risks and effectively service customers.

Enterprise Products Partners LP (an MLP) is entirely focused on the midstream sector, and it is the most integrated, operationally connected NGL midstream player in North America.

- It has been successfully expanding all along the NGL value chain, having franchise pipelines, fractionators, storage facilities, and an import-export terminal to link major NGL production centers along the Louisiana Gulf Coast and the Rockies with the major market centers at Mont Belvieu, Conway, Kan., and along the Mississippi River.

- Its alliance with Shell Oil Co. provides it a great anchor to process deepwater Gulf of Mexico natural gas as Enterprise is currently the sixth largest processor in the US with all its processing capacity in Louisiana.

- Unlike other midstream MLPs, Enterprise has successfully taken on the commodity risk of processing because its distribution is based on the cash flow generated by its fee-based NGL assets rather than on its processing operations.

The energy merchants such as Koch Industries Inc., the Williams Cos., El Paso Corp., and Dynegy Inc. continue to hold significant positions along the NGL value chain. With the exception of Koch, most of their energies, however, are currently devoted to repairing their balance sheets. With extremely tight credit, growth of the publicly traded energy merchants in this sector is questionable at this time.

- El Paso is attempting to transfer all of its midstream assets to its MLP, with its South Texas processing plants remaining in the corporation until contracts can be converted to more of a fixed-fee basis.

- Even though Williams has an MLP, Williams' NGL assets remain in the corporation. In 2002, Williams sold virtually all of its ownership interest in the Seminole NGL pipeline system to Enterprise to strengthen its balance sheet. The company currently has up for sale its Canadian processing plants and Louisiana ethylene plant with its associated midstream assets.

- Dynegy Midstream has been reducing its NGL presence over the last several years by selling non-core processing plants.

The energy merchants' retrenching leaves the integrated majors, such as BP PLC, ExxonMobil Corp., ConocoPhillips, and ChevronTexaco still holding dominant asset positions in the midstream sector.

Unlike their predecessors, majors today are much more sensitive to returns on investment and are focusing most of their attention on offshore and international E&P plays that generate higher returns.

Controlling hydrocarbon supplies from the wellhead to the burner-tip is not as critical as it was 30-40 years ago.

Most majors will continue to rationalize their marginal midstream assets and outsource midstream responsibilities to those players that are focused on expanding the business.

Many, however, are still deciding what course to take with their midstream assets, some of which were acquired from recent M&A activities.

In their current states, some of these assets are under performing either from a lack of capital, vision, or the right connectivity.

Our analysis shows that many of these midstream assets could easily "fit and groove" with each other or with other midstream businesses to create sufficient critical mass and synergies to improve their earnings potential significantly.

As previously mentioned, players that have been focused on growing either organically or by acquisitions within the sector are the MLPs. Their ability to raise capital has given them an edge to take advantage of recent turmoil.

Whether the MLPs have the most effective financial structure to continue to expand in this sector along the entire value chain is a topic for another article.

The most important point is that sector participants must have the vision, desire, and the right approach profitably to expand a midstream business because the sector needs and can support a small number of fairly integrated and properly capitalized midstream companies.

Those companies that can effectively integrate midstream assets to complement each other and that can provide strong links with customers either upstream or downstream or both will have greater success in serving the customer, minimizing business risks, and taking advantage of opportunities.

This is because, in time, the commodity risks associated with gas processing will be resolved contractually simply because the service is needed and most producers will want to focus resources on finding and producing crude oil and natural gas rather than have the processing function default to them.

A high-priced gas environment will eventually induce new supplies from Canada and possibly the McKenzie Delta, and LNG will become more of a prominent supply source where the midstream sector can play a critical role in conditioning and transporting the gas to market.

The US petrochemical industry will adjust its feedstock slate to remain competitive with foreign petrochemical producers, and NGLs will continue to be the feedstocks of choice.

The author

Peter Fasullo ([email protected]) is founder and principal of En*Vantage Inc., Houston, an energy investment and advisory firm. He began his career with MW Kellogg in 1976 as a process engineer and went on to Pace Consultants & Engineers in the early 1980s as a strategic planning consultant. Following Pace, he spent 14 years with Valero Energy Corp. In 1996, Fasullo became head of Valero's corporate development department and in 1997 became head of MAPCO's corporate and business development department. Fasullo holds BS and MS degrees in chemical engineering from Rice University and an MBA from the University of Houston.

Based on a presentation to the Gas Processors Association 82nd Annual Convention, Mar. 10-12, 2003, San Antonio.