In the next 10 years, the worldwide commodity petrochemicals industry will experience a larger fixed and variable production cost gap between the large, global petrochemical companies and smaller, regional players.

Five years of poor business conditions created these circumstances. Larger producers have reduced fixed costs by consolidating and shutting down higher-cost assets, and lowered variable costs by investing in low-cost feedstock sources. Regional producers, however, did not have merger opportunities and had limited feedstock supply selection inherent in regionally focused operations.

The flawed industry view that long-term survival depends solely on riding the profit cycle crests has caused a deeper rift in the cost structures of global and regional players.

The petrochemical industry hopes that a recovery in 2002-03 will finally bring it out of its doldrums. Another competitive force is emerging in the global petrochemical business: low-cost manufacturing in feedstock-rich regions like the Middle East. Investment plans there are risky; however, new capacity in the Middle East still represents a competitive threat.

Many companies have not done enough to compete in the new business environment of lower fixed costs and feedstock costs. Producers who want to survive in the next 10 years must proactively change their operations.

Competitive trends

The petrochemical business environment during the next few years will experience further cost competitiveness, intense competition, and uncertain demand cycles.

A supply-demand imbalance in the past few years caused these conditions and brought about capacity consolidation, which has led to fewer and larger producers.

With the capital required for a world-scale plant being small compared to total assets in Middle Eastern companies, producers have relatively easy access to capital to invest in low-feedstock-cost regions. These producers typically have a portfolio weighted toward the low end of the global cost curve.

The Middle East has become more open to investment in the past few years. Persian Gulf countries have increased foreign investment by improving foreign investor rights, reducing taxes and tariffs, and undergoing privatization schemes.

These countries have chosen petrochemical production as a diversification from oil because it provides raw materials to other manufacturing industries. The region also has good feedstock availability and cost.

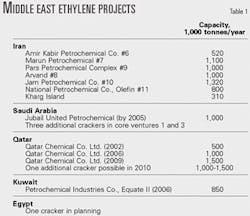

The Middle East has many cracker complexes scheduled to start up over the next 10 years (Table 1).

New cracker complexes planned for the next 10 years in Iran alone are equivalent to the current size of the Saudi Arabian ethylene industry. A delay in these projects is likely, however, especially for the projects to be completed before 2005.

Most of these cracker projects will use ethane as feedstock, with little potential for coproducts. The primary derivative is polyethylene based on market size and transportation advantages. The main feedstock to these crackers is ethane from natural gas. The remaining methane in the natural gas will be used for:

- An alternative feedstock for Middle East power plants to meet increased electricity demand. This will allow countries to export more oil for increased revenues.

- New methanol plants that will replace higher-cost capacity in market regions.

- Ammonia plants for fertilizers and derivatives.

- A gas to repressurize older oil wells.

Middle Eastern companies are still uncertain, however, whether there is a large enough methane sink for all the cracker projects.

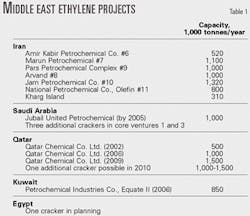

Based on our projections for industrial development and gas needs, there is still a large disconnection between gas-use forecasts and ethane-demand growth for ethylene production. Table 2 shows estimates for demand growth of ethylene derivatives.

The largest unknowns are the need for oil well repressurization and the flaring of excess methane. Nevertheless, Middle East capacity expansions account for the majority of planned future cracker projects, which are shifting the global olefins cost curve downward.

Thermoplastics

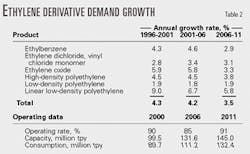

Global thermoplastics demand will grow at an annual rate of 4.8% between 2001 and 2006 (Table 3).

This compares to the historical annual growth rate of 5.5% from 1994 to 2000, and 6.1% from 1990 to 2000. Because historical growth includes a demand decline due to the Asian financial crisis, the forecast is conservative.

Polyethylene has experienced the most overcapacity during the past few years; therefore, we expect the polyethylene recovery to lag that of the average petrochemical industry. Polyethylene oversupply in 2002-06 will result in a slowdown of project approvals for post-2004 projects. The 2003-04 planned expansions are already under construction.

This implies 0.5-0.9 million tonnes of capacity shutdowns, including laggard units for high-density polyethylene (HDPE) slurry and small, aging low-density polyethylene (LDPE) units. These estimates are based on plants:

- Built before 1970, especially HDPE slurry and LDPE, mostly in Western Europe, US, and Japan.

- Located in higher feedstock-cost areas such as Western Europe and Japan.

- With less capacity; such as those in Japan, Western Europe, and, to a minor extent, the US.

Global polyethylene nameplate utilization rates should therefore remain greater than 80%. The amount of capacity that companies will shut down will partly depend on margin performance during 2002-03.

Western Europe and North America will reduce net exports of polyethylene. The Middle East will increase net exports to China despite a conservative polyethylene annual consumption growth projection for China of only 6.5% during 2001-06.

This compares to a forecast GDP annual growth rate of 7% in the same period.

Global polypropylene capacity, on the other hand, is growing slower than incremental demand.

Between now and 2006, this imbalance will create a need for 3.6 million tonnes of new capacity in excess of the 19.0 million tonnes scheduled for construction.

Polypropylene utilization rates, consequently, will increase sharply during 2002.

Just as the Middle East has an advantage in ethylene derivatives, Asia can have a similar competitiveness and opportunity in propylene derivatives because the two major sources of propylene are naphtha cracking and fluid catalytic cracking.

In Asia, naphtha cracking is more common than ethane cracking and refinery capacity is growing to meet rising fuel demand.

Refining, aromatics

Asia Pacific will have an advantage in aromatics and derivatives production because:

- New refineries to meet strong regional fuel market growth will generate large amounts of aromatics.

- A proliferation of ethane-based crackers will increase the value of Asia's naphtha-cracker-based coproducts because it is the fastest growing naphtha-cracking region.

During 2001-11, worldwide base aromatics demand will increase at about 4.1%/year for paraxylene, 3.7%/year for benzene, and 4%/year for toluene. The aromatics market will generally recover earlier than the olefins-polyolefins business.

Methanol

Global methanol demand will grow 2%/year between 2001 and 2011.With methyl tertiary butyl ether (MTBE) accounting for about 25% of methanol demand in 2001, most of methanol's outlook depends on regulations regarding MTBE's use as an oxygenate.

With California delaying its MTBE ban, US MTBE will experience a gradual decline in demand. Other countries, however, are unlikely to enact an MTBE ban.

Companies are building methanol capacity in low-cost methane regions like the Caribbean, Middle East, and potentially Chile and Australia. North American methanol producers are shutting down capacity due to higher feedstock costs.

Responding to competition

Petrochemical producers that do not benefit from economies of scale or technology advancements will suffer due to an increasingly competitive industry brought about by mergers, technology investment, low-cost feedstock investment, and uncertain demand.

There are, however, competitive strategies for long-term survival. Options for high-cost regional producers include:

- Integration for feedstock flexibility and asset optimization.

- Expanding facilities for improved economies.

- Recovering cracker coproducts instead of competing in the polyethylene market.

- Merging and consolidating to reduce fixed costs.

- Shutting down high-cost capacity to increase unit margins.

- Investing in new product, new process, and product improvement research and development

- Improving asset portfolios by investing globally, in low feedstock-cost regions, and in growing market regions.

The author

Paul Bjacek is the world petrochemical director at SRI Consulting, Houston. He has also served as a business research manager for Chevron Chemical Co. and in consulting positions with Ernst & Young LLP, Chem Systems, and the WEFA Group. Bjacek holds an MS in sea law, economics, and policy from the London School of Economics and a BS in chemistry and business from the University of Scranton, Pa. He is also past president of the Commercial Development and Marketing Association.

Correction

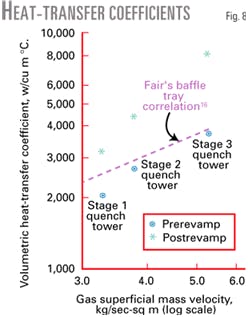

In the article, "Olefin producer uses shed decks to improve quench tower operations" (OGJ, May 20, 2002, p.50) by H.Z. Kister and S. Schwartz, Fig. 8 contained an error. Here is the correct version.