COMMENT—Beyond transparency: EITI stretches 'civil society' role

Michael Socarras

Chadbourne & Parke

Washington, DC

The Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI), endorsed by US President Barack Obama and supported by oil companies as an antidote for corruption, is becoming as much a tool of interest-group politics as it is a mechanism of transparency.

Obama announced in New York last Sept. 20 that the US and other countries have joined the Open Government Partnership to "work with civil society groups to develop an action plan of specific commitments." He added, "Today, the United States is releasing our plan, which we are posting on the White House web site and at OpenGovPartnership.org." The US National Action Plan states that the Obama Administration "is hereby committing to implement the EITI," including its "civil society" requirements. If implemented, Obama's announcement would place US oil and gas policy under a set of regulatory standards set by the EITI that, among other things, mandate participation by private interest groups—civil society—in a wide range of US government policy decisions yet to be defined.

Headquartered in Oslo, EITI describes its mission as promoting transparency in the world's oil, gas, and mining industries. There is undoubtedly a need for ideas to combat corruption and for efforts to implement them. But EITI goes beyond those goals. It prescribes 21 requirements for membership, including audits of companies' royalty, tax, and other payments to national governments; audits of the royalties, tax, and other extractive industry revenues entered on national government accounts; and a comparison of the two sets of audits to identify any discrepancy suggesting a possible diversion of funds. At the conclusion of a candidacy period, a country presents a compliance report validated by a third-party contractor that EITI's board considers to certify compliance.

Chevron, Statoil, Royal Dutch Shell, Areva, Standard Life Investments, and the International Council on Mining and Metals are the six current "companies and investors" members on the EITI board of directors. The current board alternates include ExxonMobil, BP, Pemex, Freeport MacMoRan Copper & Gold, and AllianzGI Investments Europe.

About EITI, ExxonMobil says, "We believe transparency initiatives should apply universally to all companies—publicly traded, private, and state-owned—with an interest in a country's extractive sector; protect proprietary information; and respect the laws of a host government or a company's contractual obligations. We support initiatives such as the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative, the Group of Eight (G-8) Transparency Initiative, and the United Nations Convention Against Corruption."

Countries currently certified by EITI's board as compliant are Azerbaijan, Central African Republic, Ghana, Kyrgyz Republic, Liberia, Mali, Mauritania, Mongolia, Niger, Nigeria, Norway, Peru, and Timor-Leste. Yemen's compliant status has been suspended.

Interest groups

Whatever it might be doing to eliminate corruption, EITI is no less about opaque interest group politics than it is about transparency. A careful look at EITI shows that it is a way for international activists who call themselves "civil society" to leverage the corruption issue so as to bypass institutions of the nation-state and to obtain for themselves, country by country, a seat alongside government officials when decisions are made on how countries spend their resource revenue.

EITI readily admits that it goes much further than just certifying audits. EITI's rules require each implementing state to establish a "multistakeholder group" (MSG) that includes the civil society groups to which Obama referred last September. Under EITI's new rules, adopted in 2011, a country seeking compliance certification must persuade EITI's board to approve a compliance plan developed with MSG participation and work with the MSG to design, monitor, and implement the plan. In this way the MSG is effectively institutionalized as a domestic political force in the country's policymaking. EITI is based on the premise that when people learn how much money their government takes in from oil, gas, and mining resources, a national debate will open up in which civil society groups will play a key role.

In its guidance to countries on the role of civil society, EITI criticizes "actions that have restricted public debate about revenue transparency and the use to which resource revenues are put." A look at EITI's internal deliberations shows that EITI was always designed as a political initiative, has already become a political force in several countries, and is debating how hard and how fast to push a political agenda.

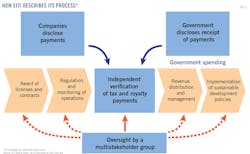

For the EITI board's Oct. 25-26, 2011, meeting in Jakarta, the EITI Secretariat produced the very insightful Board Paper 18-10 to explain (on p. 10) that, as EITI intends, "The multistakeholder group in most countries has become a basis for wider dialogue about reform." Using a diagram that the EITI Secretariat says it has used for years to illustrate "the dynamic and open-ended nature of the EITI," this Board Paper admits that EITI has long sought to involve MSGs, including so-called civil society groups, in government spending. That diagram shows a "value chain" that progresses along five links: (1) awarding of licenses and contracts, (2) regulation and monitoring of operations, (3) independent verification and monitoring of tax and royalty payments, (4) revenue distribution and management, and (5) implementation of sustainable development policies. The Secretariat's paper labels steps (4) and (5) "government spending" and indicates that an MSG would exercise "oversight" over those links in the chain (Fig. 1).

Using that paper for discussion, the EITI's Strategic Working Group began to consider last November proposals from various sources, particularly the Revenue Watch Institute, founded by billionaire activist George Soros, and the World Bank, to move even more aggressively into legal and political reform. Board Paper 18-10 stated, "The World Bank proposes new EITI criteria that would require compliant implementing countries to 'develop and implement a strategy of concretely linking and mainstreaming EITI into overarching national processes and related initiatives.'" Those include, for instance, various treaty initiatives. EITI Board Paper 18-10 expresses skepticism of those proposals not because it opposes politicization but rather because, as quoted above, in most compliant countries the MSG has already become involved in political reform.

Thus, as applied to any implementing country including the US, EITI would seat so-called civil society groups at the table of national political discussion and give them an explicitly open-ended role in debates over government spending of natural resource revenues. There is no reason to think that in the US this would stop at the federal level; state governors may find themselves sitting next to international civil society groups to formulate policy on state energy and mining revenues.

Civil society

Who are these civil society groups? A visit to http://eiti.org shows that EITI's board includes five full and five alternate members from "civil society organizations." The full members represent Soros's Open Society Forum/Mongolia, the Soros-funded Revenue Watch Institute, a Ghanaian organization called Wacam, a Congolese group whose French name means African Association for the Defense of Human Rights, and Global Witness.

The Open-Society Forum is well known for advocating Soros's ideas and goals. Its web site showcases a video about Soros in which it is claimed that he has spent $8 billion on various initiatives. Soros is shown on the video advocating a need to "speak truth to power." The Republican Party does not seem to stand for truth, as Soros sees it, and he has made no secret of his personal mission to remove it from power. On Nov. 11, 2003, the Washington Post quoted Soros as saying that removing then-President George W. Bush from office was "the central focus of my life" and "a matter of life and death."

Revenue Watch Institute says it was founded as a program of Soros's Open Society Institute. Focusing on countries rich in natural resources, it declares that "a mainstay of RWI's work is the development of civil society capacity." That means Revenue Watch funds and trains activists around the world who advance Soros's ideas, including presumably his declared mission to oppose the Republican Party's international agenda. Wacam on Aug. 27, 2008, issued a statement criticizing Ghana's political parties for failing to discuss environmental issues during political campaigns.

The African Association for the Defense of Human Rights describes itself on its French-language web site as dedicated to promoting human rights. On Feb. 13, 2012, it issued a press release expressing its concern about the "arbitrary arrest and kidnapping" of three members of the national police by members of the Republican Guard.

Global Witness promotes itself on a video on its website that briefly features an image of former US Sec. of defense Donald Rumsfeld with a voice-over about international corruption. The video concludes with a call for a "massive shake-up in the rules of international trade."

The transparency advocate EITI is itself opaque about where these board members obtain funding, except to the extent that two of them are apparently funded by Soros. There is a limit to EITI's zeal for transparency when it comes to its own civil society members.

While Obama has used the euphemism "civil society groups" to refer to these organizations, his former press secretary Robert Gibbs's reference on another occasion to "the professional left" could be just as apt.

Board dynamics

While private interest groups hold only five of the 19 permanent seats on the EITI board, they hold the balance between the royalty-paying and the royalty-collecting board members, neither of which has a majority. Moreover, EITI says its board operates by consensus, so that if interest group members of a country's MSG are unhappy about being denied influence over resource decisions, the international civil society members of the EITI board could back them up by withholding recertification and unjustly labeling the country as corrupt.

The fact that activist groups indeed control the board is indicated in its choice of chair: UK Labor Party politician Clare Short, who is best known for her vigorous opposition to US-led military interventions in the Middle East. In 1991, she resigned as party spokesman in protest at the Labor Party's stance on the first Gulf War, and in 2003 she threatened to resign again, this time from Tony Blair's cabinet, if Britain joined the US invasion of Iraq without UN approval.

Clare Short's public statements on matters of critical interest to industry members are another sign that activists hold the balance of power on EITI's board. The US Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act requires that SEC-regulated companies make certain discloses of revenues on a country-by-country and project-by-project basis. Some reports indicate that industry members of EITI's board threatened to resign if EITI were to support the adoption of a similar requirement by the EU Commission. Short told Petroleum Economist that "once the companies calm down and realize this is going to happen to them even if they don't like it, I think you'll see them use their influence to encourage other countries to join [the EITI] so that the playing field is leveled."

Also on EITI's board as full members are representatives of Niger, Nigeria, Mongolia, Indonesia, Spain, the Netherlands, and the US. The board thus has seven country votes, six industry votes, and five civil society votes plus the chair. As governments and companies typically sit across negotiating tables to resolve multibillion-dollar differences, neither side can have a controlling majority, thus allowing pressure groups to hold the balance.

Why do developing countries and companies want to be part of EITI at all? The countries, being royalty collectors, are keenly interested in knowing whether EITI-approved auditors can confirm that extracting companies are paying the royalties that they are supposed to be paying, while the companies benefit from having independent verification that royalty, tax, and other payments are not lining the pockets of government officials. Thanks to the foresight of Peter Eigen, founder of Transparency International and past chair of EITI's board, civil society groups have negotiated a seat at the table for themselves as their price for giving countries and industry the transparency they wish to have about each other.

The US role

As a supporting member of EITI, the US is not under its oversight. The US and other countries would come under EITI oversight only if they become implementing members. Obama's announcement that the US will implement EITI will bring the US under EITI oversight for the first time.

The reasons for Obama's decision are not transparent. To the extent that the Obama Administration's says that its motive is to lead by example in the fight against corruption, the rationale overlooks EITI's political goals and is simplistic.

To the leader of an emerging country with extractive industry revenues, the fact that the US is compliant with EITI standards says little about whether his own nation should be. The two countries are not comparable. If the emerging country leader decides to join EITI, it will be because of a cost-benefit calculation completely unlike anything Obama weighed when he decided to make his announcement in New York.

A different concern is whether the US should be helping EITI to create new political forces for reform that circumvent national institutions. Constitutional processes of all countries produce leaders who are supposed to represent their peoples' interests, including their interest in the wise use of oil and gas revenues as well as transparency and reform. The political side of EITI's agenda is premised on the unstated notion that national constitutions have failed to achieve that end and that, to overcome constitutional failure, EITI must insist that civil society should be consulted in resource decisions.

Several consequences follow from this. One is clearly an erosion of national sovereignty in that government officials must develop national policies in consultation with citizens of their countries who have not been selected for that role under national constitutions, but who instead are deemed representative of civil society by foreigners sitting on EITI's board. As the EITI Secretariat's board paper recognizes, in most countries the multistakeholder groups are already participating in political decisions that reach beyond audits.

Another clear and indisputable consequence is that national policies would be influenced by undisclosed foreign interests to the degree EITI deems appropriate, under threat of national decertification. This is indisputable based on the fact that EITI involves international and local activist groups in national policy-making but does not require, and in itself does not practice, fully transparent disclosure of all of these groups' funding sources.

A third consequence is that EITI undermines constitutions. The people whom a national government serves are its true civil society. The relationship between the people—i.e., true civil society—and their government is mediated exclusively by the constitution of the country. Any doubt about the exclusivity of a national constitution as the sole legitimate expression of the people's will and interests undermines the constitution. Otherwise, why should the armed forces, the clergy, or tribal chiefs be excluded from wielding extra-constitutional influence in any particular country?

Troubling notion

From the perspective of the US, the notion that EITI should certify that American public officials are not pocketing oil, gas, or mining company payments is troubling. It implies that the Constitution and laws of the US and the several states are inadequate to prevent embezzlement and to ensure public debate over energy policy. It is unclear why the US has need to invite Peter Eigen, Clare Short, George Soros, or Congolese human rights activists to help ensure US transparency. While a citizen of Ghana may not be offended to hear that his government has brought in foreign advisors to solve a purported problem, Americans may take a less sanguine view about finding themselves in the same spot.

It is also strange for EITI to welcome Obama's decision to place the US on the path to becoming an EITI compliant country. What does EITI have to offer that US institutions lack? Since the only reasonable answer to that question is nothing, EITI can only be looking to use this invitation to promote its agenda, including its goal of seating private activists at the tables of national economic policy worldwide.

There is no doubt that auditing oil, gas, and mining company payments to certain national governments, and comparing them with ledger entries on national treasury accounts, is a good and useful step for some companies and governments. It is less clear, however, that placing private pressure groups in oversight of national resource decisions is a price worth paying.

The author

More Oil & Gas Journal Current Issue Articles

More Oil & Gas Journal Archives Issue Articles

View Oil and Gas Articles on PennEnergy.com