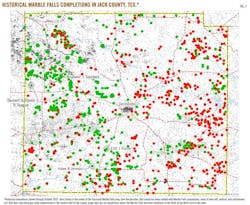

Marble Falls horizontal oil play developing in Fort Worth basin

James D. Henry

Old Aulacogen LP

Frisco, Tex.

At about the time in the mid-20th century that the Fort Worth basin of North Central Texas was being abandoned by the major oil companies as a worn-out backwater area, a young man named George Mitchell began drilling there for Pennsylvanian-age Atokan (aka Boonesville Bend) sandstones and conglomerates. Mitchell Energy eventually became the largest independent oil and gas company in Texas, and George Mitchell became a billionaire.

By 1980 the Atoka had been pretty well exhausted. George Mitchell began drilling deeper gas wells in the late Mississippian Barnett shale and experimenting with massive frac jobs and new stimulation techniques. By the turn of the millennium, the Newark East (Barnett) field had become the largest gas field in Texas both in terms of monthly production and areal extent.

As the Barnett play is now reaching its mature stage in the second decade of the new century, yet another play is rapidly developing in the Fort Worth basin. It involves the early Pennsylvanian-age Marble Falls formation.

Occurrence of the Marble Falls

Originally named by R.T. Hill from outcrops in Burnet County, Tex., in 1889, and like the previous play in the Barnett, the Marble Falls consists of a vertically fractured reservoir rock that has rather poor primary porosity and is most productive from horizontal boreholes.

Unfortunately, the stratigraphy of the Marble Falls, and indeed that of all the rocks in the Fort Worth basin that are sandwiched between the overlying Atoka and the underlying Barnett shale, is poorly understood and has rarely been studied or described in the literature.

Many Texas researchers, beginning with Ferdinan Roemer in 1847, have described the Carboniferous rocks at their surface outcrops on the northern edge of the Llano uplift, but there is a dearth of published information about those same—or near equivalent—rocks in the subsurface, and what little is available is regrettably repetitive and inaccurate.

It has long been the practice for unwary geologists studying the Fort Worth basin to lump all the rocks between the base of the Atoka section and the top of the petroliferous facies of the Barnett shale into a single large heterogeneous lithologic taxon called "the Marble Falls." In fact, that rock sequence in the subsurface consists of two distinct lithologies deposited by two separate and discrete sedimentary events that are separated by an angular unconformity that cuts out at least a dozen million years of time-rock in this basin.

The Mississippian/Pennsylvanian unconformity is well known throughout the Midcontinent, and we should be very surprised if we could not find it in the rocks of North Central Texas. Clearly we are dealing with two formations between the Atokan/Bend conglomerates and the Barnett shale, and it is not clear that either one of them is exactly correlative with the true Marble Falls of the outcrop.

Throughout most of the basin, the top of the Barnett shale is readily identified on conventional wireline logs. It is substantially more radioactive than any other shale in the basin, and its mean bulk density of about 2.50 g/cc makes it noticeably lighter than any of the other Carboniferous shales.

But mud loggers frequently have trouble calling the top of the Barnett while drilling because the immediately overlying limey shales and shaley limestones are lithologically extremely similar in color and texture. This similarity results from the fact that the typically greasy Barnett facies and the rocks that conformably overlie it were all part of a single depositional event that occurred during the Chesterian Stage, the youngest of the four recognized North American stages that make up the Mississippian (Lower Carboniferous) Period of the Paleozoic Era.

Whatever the depositional environment factor was that made the lower part of the Barnett so light and radioactive, it ceased, or migrated laterally, rather abruptly at some point in the 15-million-year duration of Chesterian time, but the other lithologic constituents of the Barnett continued to be deposited without interruption in a relatively calm, shallow epicontinental sea.

In parts of the Fort Worth basin, the depositional environment of the bituminous Barnett returned for a brief encore and left a couple dozen feet of typically petroliferous shale 100 ft or so above the main mass of Barnett lithology. Industry geologists commonly refer to it as the "false Barnett" or "upper Barnett."

Sandwiched in between the main Barnett and the false Barnett is a mostly calcareous interval that is believed to be very nearly the stratigraphic equivalent of the Forestburg limestone in southeastern Montague County.

Today, almost 450 ft of post-Barnett, Chesterian rocks can be found in the northwestern corner of the Fort Worth basin near the Jack/Young County line between the hamlets of Jermyn and Loving. Those strata are overlain unconformably by lithologically distinct sediments of a Pennsylvanian formation that is—correctly or otherwise—referred to as the Marble Falls.

Describing the Marble Falls

The true Marble Falls of the Fort Worth basin is a very impure calcareous rock that contains a remarkably large percentage of silica in the form of sponge spicules, quartz sand, and-or conglomerate, in addition to shale.

The lithology varies to a significant extent both vertically and laterally. One of the more common facies is an argillaceous limestone that exhibits a "salt and pepper" texture under the microscope.

In some areas of the basin, it is more of a calcareous sandstone than a sandy limestone, and it is technically more correct to refer to it as the Marble Falls formation rather than the Marble Falls limestone. This fact has only come to light within the last few years with the availability of better quality wireline logs and the acquisition of cores in some key areas.

The sand grains, which are virtually absent from the underlying Chesterian sediments, are likely derived from the Ouachita fold belt that was rapidly advancing towards North Texas from the east during the relatively brief 4-million-year time span of the Atokan Stage of the early Pennsylvanian Period.

The best description yet published of the subsurface Marble Falls is the 2010 master's thesis of Klinton M. Farrar at Texas Christian University.1 Farrar had access to about 280 ft of whole cores through the Marble Falls in the EOG 1 House well (42-237-39288) in southwestern Jack County.

He describes half a dozen different facies within the formation, but in general the Marble Falls consists largely of (1) bioturbated, spiculitic siltstones with subangular detrital quartz and (2) black, extremely fissile claystones. The beds contain abundant fossils of sponges, crinoids, agglutinated forams, bryozoans, echinoderms, and nautiloids. The basal few inches of the formation include a conglomerate of unidentifiable shell fragments (Fig. 1).

In the northeastern quadrant of Jack County is a local area where we can very clearly see the sandy limestone beds of the upper Marble Falls grading laterally into the lowermost shales of the Atokan shales and conglomerates. Consequently, there can be no question that the upper Marble Falls and the lowermost Atokan/Boonesville Bend beds are all part of a single continuous sedimentary event that covered North Texas and the Fort Worth basin after some unknown thickness of Chesterian (and perhaps Morrowan) rocks was removed by erosion. No regional unconformity higher in the Pennsylvanian and-or Permian section of North Texas has ever been documented.

The time-rock hiatus between the preserved Chesterian and Atokan strata in the Fort Worth basin includes the entire 6 million years of the Morrowan age. Whether or not Morrowan sediments were ever deposited in the deep part of the basin is unknown, but it appears that they might have been.

Frederick Byron Plummer studied the fauna of the type Marble Falls at the surface outcrops in Central Texas and concluded that that limestone formation was upper Morrowan.2 However that may be, there is no evidence for extant Morrowan age rocks in the subsurface of North Central Texas. Plummer also concluded that the Barnett shale was Chesterian, and on that there is general agreement.

The post-Barnett beds of the Chesterian Stage do not outcrop at the surface and have never been named or even described in the literature. We could, if we like, just refer to them as "the Chester," while trying to remember that they are not the only Chesterian rocks in the basin. But other Mississippian rocks elsewhere in North America already bear that Chester designation, and there is enough duplication and redundancy in the geological literature as it is.

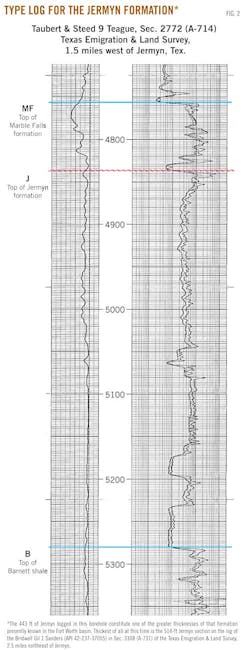

If we must give this interval a formational name—and it certainly deserves one—I would propose the "Jermyn formation," after the eponymous little hamlet in west-central Jack County near which this rock unit reaches its maximum preserved thickness. To that end, the dual induction log of the Taubert and Steed 9 Teague well (42-237-35307) that was drilled in 1983 in Section 2772 (A-714) of the Texas Emigration & Land Co. Survey about 1.5 miles northwest of Jermyn will serve as the type log for this formation, and the interval from 4,837 to 5,280 ft therein is here designated the type subsurface section.

Describing the Jermyn formation

The Jermyn formation consists mostly of massive limestones that appear to be extremely dense on the bulk density logs (circa 2.70 g/cc) and extraordinarily clean on the gamma ray log—cleaner, in fact, than any other rock unit in the Fort Worth basin (Fig. 2).

Farrar's thesis explains the high density readings as micritic limestones with interbeds of dolomitic claystone that "occur every 2.4 to 14 in. and are 0.6 to 3.0 in. thick." These massive rock units are occasionally separated by less massive shale beds that do not closely resemble either the petroliferous Barnett below or the Atoka shales above.

The Jermyn carbonates are gray to dark gray and completely nonfissile, and the shales are invariably black. The differences between these two formations are as evident in the core as they are on the log. Both formations are extensively fractured both vertically, horizontally, and at all angles in between. Some of the fractures have been completely healed with quartz and-or calcite, some partially so, and some not at all.

Unlike any other formation in the Fort Worth basin, deposition of the Jermyn was largely cyclical. Depending upon the degree to which pre-Atokan erosion has breached the formation, the number of preserved shale/limestone cycles in any given borehole may vary from a mere fraction of the first one to almost all of the third (or fourth) one. How many more there may have been originally, we cannot say, because a full original section of this unit is nowhere preserved.

Together, the Jermyn and the Marble Falls occupy a vertical interval of very approximately half a thousand feet throughout most of Jack County. The two formations thicken and thin in an inverse manner with each other so as to suggest that the Marble Falls was deposited on a gently rolling near-shore Jermyn terrain and preferentially filled in the paleotopographic lows.

Based upon geochemical analyses, Zumberge et al.3 determined that the Barnett is the source rock for the large majority of producible hydrocarbons in the Fort Worth basin but left open the possibility that other strata may have contributed thereto. The shale beds of the Jermyn, especially in the lower part of the formation, are bituminous to a very substantial degree, and they may have served as source rocks also. It is equally possible that those shales, because of their close proximity to the underlying Barnett, were simply contaminated by hydrocarbons that originated in the latter formation.

A short distance west of the Fort Worth basin, on the Bend arch and the Eastern Shelf of the Midland basin, the nomenclature changes and rocks exactly equivalent to the Marble Falls are often referred to as "the Duffer." From what we can see on the wireline logs, the lithology of the Duffer is not significantly different from the true Marble Falls of the Fort Worth basin, and it is a very common, though historically unspectacular, reservoir rock.

The Comyn limestone

There is, regrettably, yet another name for the Marble Falls that is occasionally bandied about the Fort Worth basin without regard for its original definition.

The Comyn (rhymes with "Roman") limestone first appeared in the literature when it was defined—but not described—by Marcus Cheney4 in 1940 as being "that portion of the Marble Falls that occurs in the Ranger [Eastland County, Tex.] area." Cheney named the unit for a small village in the J. Walker Survey (A-988) of northeastern Comanche County that was being used at the time by Humble Pipeline Co. as a storage and pumping facility for crude oil being transported from West Texas to refineries on the Gulf Coast.

The Comyn, of course, does not outcrop anywhere, so Cheney chose for a subsurface type section the interval between 4,132 and 4,320 ft in the Roxana 1 Seaman well in the extreme northwest corner of the J.B. Hart Survey (A-1874) of west central Palo Pinto County 50 miles away. Moreover, the Roxana well was drilled in 1918-19, long before even the most primitive electric logs were available.

Cheney published this new formation based solely upon a description of the Roxana drill cuttings by Marcus Goldman of the US Geological Survey in 1921. Cheney himself never saw those cuttings, which he said were "no doubt on file with state and national geological surveys." Other than that he made no effort to document the cuttings' location or accessibility.

Fortunately, we are able to refer to that same depth interval in commonly available wireline logs of boreholes that have been drilled within a couple of miles of Cheney's type log in more recent decades. In comparing these logs to the Comyn's designated depth in the Roxana well, it is clear that Cheney did indeed give a new name to the Atokan-age Marble Falls that immediately overlies the Jermyn formation in most of the Fort Worth basin. What is not apparent is why the Marble Falls needed a new and different name in "the Ranger area," whatever Cheney considered that to be.

As a matter of taxonomic practicality, the Comyn should be deprecated in favor of the Marble Falls and-or the Duffer. The Comyn should not be confused with the Jermyn, i.e., the post-Barnett Chesterian beds, although that is a common error of industry geologists who are not familiar with the origin of the name.

References

1. Farrar, Klinton M., master's thesis, Texas Christian University, 2010 (http://etd.tcu.edu/etdfiles/available/etd-04222010-092918/unrestricted/Farrar_thesis.pdf).

2. Plummer, Frederick Byron, University of Texas Pub. No. 4329, 1950, issued posthumously.

3. Zumberge et al., "Oil and Gas Geochemistry and Petroleum Systems of the Fort Worth Basin," AAPG Bull., Vol. 91, No. 4, April 2007, pp. 445-73.

4. Cheney, Marcus, AAPG Bull., Vol. 1, January 1940, pp. 65-118

The author

Jim Henry ([email protected]) is an independent consulting geologist doing business as Old Aulacogen. He was born and raised in the Fort Worth basin. He worked for Mitchell Energy & Development Corp. and authored one of the earliest papers on the Barnett shale. He has worked the Anadarko basin with Core Oil & Gas and Beard Oil. He has a BS in geology from the University of Texas-Austin.