High cost of maintaining Eagle Ford roads strains DeWitt County

Rachael Seeley,

Editor

CUERO, Tex.-Development of the Eagle Ford shale has transformed rural DeWitt County, Tex., into one of the top oil and gas producing counties in Texas, bringing with it a welcome economic stimulus. However, the county's asphalt and gravel roads were not designed for the accompanying increase in heavy truck traffic, and the county is now looking to the state for help funding an unprecedented rise in road spending.

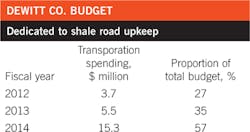

From 2012 to 2014, the county road budget rose four-fold to $15.3 million to meet the growing cost of maintaining the county road system (see table, p. 4). "For the weight of the trucks, the volume of the trucks, and the fact that it's mostly two-way traffic, we just had a road system that was wholly inadequate," County Judge Daryl Fowler told UOGR.

Road spending accounts for 57% of the county's 2014 budget, which, at $26.5 million, is the largest budget DeWitt County has ever passed. "We just had to take these emergency measures" to pay for road damage, Fowler said.

The Eagle Ford shale lies beneath about two thirds of DeWitt County, and the county maintains about 342 miles of roads affected by shale development-or roughly half of its 690 miles of county road.

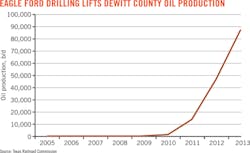

DeWitt County is now the second-largest producing county in the Eagle Ford. County-wide oil production soared from 440 b/d in 2009 to 80,500 b/d in the first half of 2014 (see figure). Thirty-two rigs were active in mid-June, representing 8.6% of all rigs working in the shale play.

Heavy truck damage

In 2007, the state of Texas issued 69 well permits in DeWitt County. The number of permits has risen steadily since then, reaching 449 in 2012. A report by the Texas Department of Transportation report about 1,200 loaded trucks are needed to bring one gas well into production.

Fowler said oversized trucks weighing 125,000-150,000 lb frequent the county roads. These loads gradually crush gravel into dust. Over time, the crowning of the road that directs rainwater into the gutter is lost and ruts form, exposing the native soil beneath. Fowler said the damage is most apparent after rainstorms, when water pools in the ruts, transforming them into mud pits that make it difficult to move rigs, water, equipment, and product.

He cited an example: In January 2012, a major storm dropped about 6 in. of rain along the DeWitt and Gonzalez county line. Water pooled in the native soil exposed by ruts in the road, transforming it into mud that, Fowler said, created transportation difficulties for Rosetta Resources Inc., which was active in the area.

Fowler said the county road around Rosetta's leasehold "became quicksand, and their tanker trucks laden with product got stuck. They had beautiful lease roads and then-when they got to that gate and had to navigate that next 1 mile [of county road] down to the state highway-they were getting stuck. They had to use bulldozers and cranes to move those trucks."

To address the problem and avoid production delays, Fowler said, Rosetta volunteered to donate material to rebuild the road around its leasehold if the county provided labor and equipment.

Fowler said the completed project cost $250,000; Rosetta donated nearly 10,000 tons of gravel, valued at $200,000, and the county provided labor and equipment valued at $50,000.

Rosetta is not the only producer that has offered assistance repairing roads. In the summer of 2010, Petrohawk Energy, now owned by BHP Billiton, volunteered to donate $8,000 for each well drilled during a 2-year period to help cover road damages. Pioneer Natural Resources Co. followed suit. Together, Fowler said, the producers donated $2.6 million to the county over a 2-year period.

"It was a huge benefit to us-we couldn't keep up, but we didn't get behind," Fowler said about road damage.

Omar Garcia, president of the South Texas Energy and Economic Roundtable, an oil and gas trade group, said industry has been proactive in efforts to work with county judges and municipalities to address road needs-providing equipment, materials, and in some instances funding.

"If an oil and gas company is damaging the roads they will go and repair them. They will work with the counties to repair them because it's very important that we have a very robust transportation system to get the product to market," Garcia told UOGR.

Funding constraints

Although Eagle Ford drilling and associated truck traffic in DeWitt County rose sharply in 2010, the county did not see a corresponding increase in property tax revenue to fund its annual transportation budget until January 2012.

This is due to the the manner that property tax collection is organized in Texas. Once a well is spudded there is a delay of up to 2 years before the county collects associated property taxes. For a well spudded on Feb. 1, 2014, Fowler said, the county cannot appraise the value of the minerals until January 2015, and property taxes are not due until January 2016.

"There's this huge lag, and that was crippling us," Fowler said.

DeWitt County commissioned an engineering study of road maintenance needs. The Road Damage Cost Allocation Study, issued in 2012, found that the county road system was designed to handle light, local traffic. Most roads have a 4-6-in. thick sand and gravel base on top of native soil, which is sand, and topped with asphalt surface treatments.

"The anticipated traffic on this type of road would consist of passenger cars, pickup trucks, and about two 18-wheel tanker trucks (80,000 lb each) per week," the study said.

It found that upgrading the country road system to meet the needs of the energy industry would cost $432 million, higher than DeWitt County's entire, record-high budget for fiscal year 2014. Included in the estimate was the cost of widening 99 miles of road to three lanes from two and deepening the roadbeds to 16-18 in. at a cost of $1.9 million/mile.

Tax revenue constraints

Appraised property value in DeWitt County has risen 10-fold in the past 3 years, due largely to an increase in the value of mineral rights in the Eagle Ford shale. When Fowler took office in 2011, the county's appraised property value was less than $1 billion. This year it is expected to reach $10 billion.

However, Texas tax law prevents the county from collecting a proportionately higher amount in property taxes-its primary source of funding.

Texas law caps growth in county property tax revenue at 8%/year. For a county that has seen a leap in appraised property tax value, such as DeWitt, this means that the property tax rate must be reduced in order to stay below the 8% revenue growth threshold. If a county exceeds this limit, Texas law provides a 90-day window during which citizens can collect signatures to call for a rollback election to vote on reducing the tax rate to the capped level.

Fowler said that reducing the property tax level to keep revenue collection below the 8% growth threshold would have left DeWitt County short of the funds needed to maintain its roads. So Fowler took a risk his second year in office-opting to keep the same property tax rate and enabling the county to collect more revenue.

To prevent calls for a rollback election, Fowler and his staff pledged to dedicate as much of the increased tax revenue as possible to roads. "We went to the electorate. We went to the newspapers, the Rotary Club, the Lions Club, the Young Farmer's Club... anybody that would listen," Fowler said.

No rollback election was called. The next year, 2012, property tax revenue increased to $11.25 million from $7.5 million. Of that, 72% was attributable to oil and gas production.

While the bulk of increased tax revenue is being dedicated to roads, Fowler said, Eagle Ford shale development has also increased demands on other county functions. More courthouse staff is needed to handle increased civil suits-many related to real estate, along with pipeline right-of-way condemnations and family mineral right disputes. The needs of the sheriff's department have also risen, as the department contends with increased traffic accidents, road fatalities, and traffic control.

Regardless, Fowler feels strongly that the county should not borrow to finance support for boom-time development. "Our position, our budget policy, is for this to be paid for as we go along and use the tax base, as it grows, to be the funding vehicle to rebuild the roads," Fowler said.

State collects severance taxes

Rather than incur debt, Fowler would prefer to see the state of Texas return to the county a portion of the severance taxes collected on local oil and gas production. Last year, Texas collected $244.2 million in severance taxes on DeWitt County production.

The state taxes oil production at a rate of 4.6% on the market value of production and gas at a rate of 7.5%. Last year, DeWitt County ranked second in the state in terms of severance tax collection. Only Karnes County, also in the Eagle Ford play, contributed more, at $344.4 million.

The allocation of severance tax revenue is benchmarked to a threshold set in 1987. Collections greater than the $1.132 billion collected that year are divided between the state's Permanent School Fund (25%) and the Economic Stabilization Fund (75%), better known as the Rainy Day Fund. The two funds split about $2.5 billion in fiscal year 2013 as state oil production soared to 30-year highs.

Of that, $1.9 billion was deposited in the Rainy Day Fund, bringing the total account balance to $6.2 billion, the state's Annual Cash Report 2013 shows.

Fowler would like to see a portion of the severance tax revenue now allocated to the Rainy Day Fund dedicated to counties where severance tax revenue was generated. Up to 25% of the severance taxes remitted to the state is deducted from the royalty owner's share of production based on the royalty terms agreed to in each lease.

Fowler would like to see a portion of the royalty owner's severance taxes returned to the county where production took place. The revenue, he said, could be used to pay for road damage and increased county services. He characterized the current severance tax formula as a "free lunch" for the state at the expense of the county.

Legislative progress

Texas took a step toward making more money available for roads during the 2013 legislative session. The passage of House Bill 1025 appropriated $450 million to state and county roads damaged during energy development. Of this, the Texas Department of Transportation (TXDOT) received $225 million, and $225 million was divided among counties in the form of formula-based grants outlined in Senate Bill 1747. DeWitt County received a $4.9 million grant and must match 20% of that amount with county funds.

More relief could be on the way. On Nov. 4, 2014, a state constitutional amendment will be on the ballot that would allocate a predictable, reoccurring amount of severance tax receipts to road infrastructure. The amendment, SJR 1 or Proposition 1, calls for dedicating a portion of severance tax revenue collections that exceed the 1987 threshold to the State Highway Fund.

"The bill would take the 75% and divide that in half so that half of the money that the Rainy Day Fund is currently receiving would be diverted to the state highway fund and the remaining 25% would be retained by the Permanent School Fund," Fowler said.

"Proposition 1 would transfer one half of the present Rainy Day Fund revenue to the new Transportation Fund while maintaining the present level of funding going into the Permanent School Fund," Fowler said.

TXDOT said passage of SJR 1 could generate as much as $1.2 billion/year for the State Highway Fund for several years.

However, TXDOT estimates it needs up to $5 billion/year to address statewide roadway needs, and the language of the amendment does not guarantee any money will be distributed to energy producing counties. TXDOT funds are used on state highways, while counties are obliged to maintain local roads using local tax dollars. Most of these funds would likely be used by TXDOT to address needs in the state's fast-growing urban areas.

Economic growth

Road damage notwithstanding, Eagle Ford shale development has also generated numerous economic benefits for DeWitt County.

Before the Eagle Ford boom, Fowler said, the biggest economic activity to arrive in Cuero-the seat of county government-was a state prison constructed 20 years ago. The county was until recently classified as economically disadvantaged by the state of Texas.

Today, energy development is attracting new residents and businesses. Several major oil companies-including EOG Resources Corp., Pioneer, and BHP Billiton Petroleum Inc.-have established offices in Cuero.

To accommodate a growing workforce, the number of hotel rooms in the town is set to more than double to 599, and a developer has broken ground on the town's first new subdivision in more than 20 years. The 150-acre development, The Quarry, will include 224 single-family homes, an elementary school, and potentially the town's first unsubsidized apartment complex.

Charles Medcalf, president of Medcalf Custom Builders, developer of the subdivision, said there is pent-up housing demand in Cuero. Medcalf's sales office, an unmarked trailer on the development site, receives about two walk-ins a week despite spending no money on advertising. "We're seeing an influx of new residents," Medcalf told UOGR. Most of the prospective buyers are "extremely well-qualified," he said.

Further signs of economic development are visible throughout the city.

Last year, Pioneer opened a 90,000-sq-ft Eagle Ford shale operations center in Cuero. Other developments include a new Chrysler dealership, a new HEB grocery store, and potentially a second dormitory-style worker housing facility.

"We were a sleepy little town, then, all of a sudden, this big wave came in," Fowler said.

Looking ahead

The judge is keeping an eye on the long-term picture despite the current economic stimulus. Eagle Ford shale drilling will one day come to an end, he said, and when it does he wants to ensure the DeWitt County residents and businesses that remain are not left to service debt taken on during boom times.

"There's always a bust. Even if there is not a bust, once the last well is drilled the [production growth] bell curve turns in the opposite direction and you have about a 2-year window before those wells deplete to a minimum value for held-by-production purposes," Fowler said. Once those rigs have moved away, the county will be left with a declining tax base that is also parabolic, and any financial needs that were not addressed and paid for during boom times will be left for those that remain.

"That's a capital sin in my book. The local people didn't create the damages and should not be left with a magnified cost to repair," Fowler said.