Ohio seeks sustainability from Utica development

Tayvis Dunnahoe, Editor

ATHENS COUNTY, Ohio—The Ohio Geological Survey estimates the Utica/Point Pleasant reserve potential at 1.96 billion to 8.2 billion boe. In preparation for the current boom in Ohio, local leaders are looking to educate themselves on the best means to contribute to the increase in economic activity.

The Voinovich School at Ohio University, which focuses on transformative programs of job creation and real-world education for Ohio's next generation of entrepreneurs, recently held its second annual Appalachian Ohio State of the Region conference, titled "Shale and Beyond," at Ohio University in Athens, Ohio.

"Moving economies forward on a regional basis is hard work," said Doug O'Brien, US Dept. of Agriculture acting undersecretary, rural development.

Importance of planning

Fitting with this theme, the conference focused on local examples of how communities are working with industry to address public concerns and to develop sustainable jobs from the early phases of development.

"The issue of Ohio's current shale boom is like two sides of a coin," said Glenn Enslin, former director of Economic Development for Carroll County. "Everyone is aware of the political side."

Carroll and Harrison counties are the epicenter of Ohio's Utica shale play. "We've seen a huge boom there," Enslin said. According to Enslin, property that would have languished on the market for months has recently been selling in record time. In one case, a property listed for $899,000 sold in 2 days.

The county has seen 20 to 25 companies show up in the last year. One local hardware store has doubled in size to meet local demand. "My regular gas station went from two employees to seven to deal with the drastic increase in traffic," Enslin said. "Exponential growth in the region is one side of the coin, with the other side being the bust that often follows."

Ohio is no stranger to the boom and bust cycles inherent to natural resource developments. "The timber industry came here 150 years ago, and they took the trees and the money and left leaving denuded hillsides, polluted streams, and thousands of people without jobs," Enslin said. He cited the coal industry as having a similar effect on the state. Not unlike most of the participants in the conference, Enslin urged local communities to think about taking a different approach. "There has to be a way to turn this boom into sustainable developments that will last," Enslin said.

"There's a huge shift when it comes to energy development and community planning all across the United States. What you do in Washington, Carroll, or Williams County can be uniquely different in regard to a number of things," said Dale Arnold, Director of Energy, Utility, and Local Government Policy with the Ohio Farm Bureau Federation. "Oil and gas is just one part of it. What communities learn from these efforts will serve them extremely well when other energy resources begin development."

By 2025, 25% of the nation's needs for fuel and electric generation will come from on-farm resources, whether through providing feedstock or accommodating large, medium, and small generation, transportation, and distribution facilities on farm grounds. "You might see it from your backyard" Arnold said. Although, he added, installing infrastructure on existing farmland can be done successfully with the proper amount of planning and engagement.

"Are we going to do this alone in agriculture? No," Arnold said. The process will be a coordinated effort between project developers, government regulatory agencies (i.e., towns, state, and federal), economic development groups, and community stakeholders. "As we say in the farm business, if you are not at the table negotiating and advocating for your particular position, you will be part of the menu," Arnold added. From the Farm Bureau's perspective, project developers benefit from early engagement with the public. Working with people through education and outreach programs sooner can ease development concerns in local communities.

"We're really trying to educate one another and understand what the issues are, and then find the opportunities," said Cambridge Area Chamber of Commerce President Jo Sexton. Located in Guernsey County, Sexton's organization was an early adopter of community involvement when operations began in the Utica. "Our first information meeting attracted about 45 members, and within several months it grew to over 200," Sexton said. She added that during the early phases of development, the Chamber of Commerce was not equipped to speak about unconventional technology or environmental impacts. "We can speak on business development," she said, "These discussions are key to capitalizing on the opportunities inherent to oil and gas operations in the region."

As a result, the local population has remained much more informed about the issues. Local newspapers have added special coverage on oil and gas information, and the area is growing economically. "The worst thing communities can do is not embrace the opportunity that development brings," Sexton said.

The general role community planning organizations play in Ohio's shale development is to capture longer-term economic opportunities, which is crucial for avoiding boom/bust economic cycles. From a business perspective, a heavy focus in the area of supply chain development such as polymer and metal fabrication, supplying feedstocks, and developing uses of the affordable energy derived from Utica development will benefit the region as drilling activity eventually slows and the play moves into full-scale production.

Supply chain economics

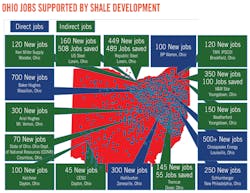

A major benefit to the US energy boom is jobs creation in areas such as Ohio. "The overall economic growth has slowed in 2013, although we expect it to reach about 2% this year," noted Brendan O'Neil, managing director, IHS Public Sector Consulting. It is expected that Ohio will be among the highest performers through 2014 with the current resource development in the state. "The real story to Ohio's improved economy is about supply chain development," O'Neil said. Increasing awareness among Ohio's local suppliers will have an exponential effect on increased upstream activity.

Direct effects such as employment are already increasing in the region. An indirect effect of Utica development will be in terms of more suppliers doing business with operators working in the state. "Ohio and Illinois are interesting cases in the field of unconventional resources," O'Neil said.

Illinois, based on IHS's recent economic impact study, "America's New Energy Future: The Unconventional Oil and Gas Revolution and the US Economy," is not considered an oil- and gas-producing state based on a number of parameters; however, it stands to gain from neighboring regions through developing its supply chain. "Both Illinois and Ohio produce a wide array of manufactured goods that find their way into upstream activity," O'Neil explained. The core of Utica activity is centralized in the condensate-heavy center portion of the play, primarily in Jefferson, Harrison, Guernsey, and Carroll counties. The oil-prone western portion is shallow with very low pressures, and the eastern portion contains very deep (8,000 ft), mostly dry gas, which makes the economics of drilling in these areas less desirable.

"Unconventional resource development is more than just about drilling," said Scott Miller, director of Ohio University's Consortium for Energy, Economics, and the Environment (CE3), which is part of the Voinovich School of Leadership and Public Affairs. From a supply chain perspective, the shale boom is represented by the sum of its parts. With an average frac spread as an example, all of its components—valves, flexible hoses, gaskets, fittings, steel parts, etc.—are produced in Ohio. "Companies interested in being included in this supply chain should be on top of their regional Chamber directors to encourage education and to increase awareness opportunities," Miller said. "Oil and gas activity will have a ripple effect in Ohio's economy."

CE3 recently completed a grant in which it audited what it believed to be the primary region benefitting the most from supplying operators and drilling companies working in Ohio. The 12-county region (see map) includes counties that will not necessarily produce oil and gas from the shale, but these counties will have opportunities to strengthen their businesses through close associations with industry needs.

According to Miller, there are a number of opportunities for Ohio's business community to get involved locally. The organization is working to spread awareness throughout the state. CE3 has developed a database of more than 1,300 companies in the region that manufacture items useful to the oil and gas industry. Such awareness and accessibility to the oil and gas industry are key to helping Ohio stay ahead, Miller said. Aside from parts and service supply, Ohio also is experiencing a return to manufacturing because of an increased need for infrastructure development. "We are actually witnessing steel jobs coming back into the Mahoning Valley," Miller said.

Supply chain enhancement, new processing facilities, and increased drilling activity are each providing economic benefits in Ohio. "We want to use these activities and incorporate manufacturing from Ohio into this supply chain," said Eric Planey, international business attraction vice president with the Youngstown-Warren Area Chamber of Commerce. According to Planey, shale is bringing increased capital investment to and reviving industrial manufacturing in the area. "We're very proud of that," he said.

As early as 2008, the area saw the construction of a new steel mill to supply operations in the Marcellus shale. "The US energy industry will help Ohio work into the international market as well," Planey said, as manufacturers worldwide are looking to cheap and abundant natural gas in North America to fuel future manufacturing projects. Once developed, Ohio's Utica gas production could become a primary feedstock for new manufacturing. In Youngstown alone, 15-17 Houston-based companies have set up shop with direct relation to Utica oil and gas activity.

Planey also sees job growth as another strong indication of Ohio's success. He noted that the state recently collected record income taxes of more than $1 million. But rapid job growth can be problematic in areas where the workforce is primarily untrained and inexperienced. Employing members of the local community in as many positions as are available is a stated goal of community leaders in Southeast Ohio. In addition to retraining workers, many organizations are turning toward specialized training organizations and academia for opportunities to improve their workforce capabilities.

Importance of education

"Well over 38,000 people were employed in Ohio in the oil and gas industry as of January 2013," said Rhonda Reda, executive director of the Ohio Oil and Gas Energy Education Program (OOGEEP) and the Ohio Oil and Gas Foundation. The state has 65,000 active wells in 49 counties. "Unconventional resources development only supplies a portion of the job opportunities in Ohio's oil and gas industry," she said.

OOGEEP, which is funded by the oil and gas industry, originally looked at the Utica shale in 2008. At the time, most companies were skeptical about the area's potential. "By 2012, we've seen reinvestment in the region of about $10 billion," Reda said, although—returns have been hindered by lack of pipeline capacity, processing, and refining capabilities. However, Reda and other area participants are certain this will change over time.

As opportunities increase, companies and learning institutions will benefit from better understanding the oil and gas industry. "Companies lose opportunities through not knowing industry terminology," Reda said. Colleges and technical schools should work to understand what professions are involved in developing oil and gas projects—more than 75 specialized professions.

In Ohio, few colleges offer advanced degrees in petroleum engineering. However, the trades are taught in depth. "Diesel mechanics, machinists, well tenders, commercial drivers, and mechanics will be the top five trades needed to successfully develop Ohio's unconventional resources," Reda said, adding that the state has done a disservice by not focusing on the trades as "that's where the biggest shortage will appear."

While petroleum engineers will typically move with the company into new areas, OOGEEP is identifying ways to bring newer generations of workers to the region. "We've audited many schools in Ohio to determine which colleges and trade schools have the highest quality training programs. Many also meet API standards to develop graduates that are well suited to work in the oil and gas industry," Reda said. The organization has worked with many training centers to update their curricula for this purpose. It has since unveiled its list of 70 Ohio colleges, universities, and trade schools that are industry-vetted and approved.

In other cases, a few Ohio schools have taken their own initiative to train students to meet the rising demand for oil and gas workers. "One thing we've struggled with is getting our students onto a well site, mostly due to liability and safety concerns," said Tim Snodgrass, project director of Energize Appalachian Ohio Grant at Zane State College. "Even on those rare occasions when we can make it onto a well pad, the students are relegated to observation," he added. While observation is key to learning certain processes, hands-on experience is also a valuable component.

About a year ago, the energy team at Zane State College decided to use its remaining job training grant to purchase equipment for its oil and gas programs. The result was an onsite training facility, or "land lab," featuring a closed-loop production facility that pumps oil 18 ft below the surface to a storage tank 125 ft away. "We didn't build it in response to industry needs but rather to those of our students," Snodgrass said. As classes discuss operations in the classroom, students now have a well pad to attend to for review. "We've had good responses from our local contractors," Snodgrass said. "We couldn't have built it without their help," he said, noting that local companies contributed nearly $2 in goods and services for every $1 the school invested.

The 2-year program has about 24 students currently enrolled. "In the absence of an industry-recognized credential, we focus on giving the students a good background in oil field operations and the science involved," Snodgrass said. The program's students have an average age closer to 30 than 20. "Most of our students returned to school to land a better job," Snodgrass said. "Unfortunately, the industry sometimes plucks a few before they have finished the program."

The program began in 2011 and enrollment has been as high as 40. The program's first graduating class saw 12 students complete the program, with half of those having landed jobs. While many of the program's students find employment prior to completion, Snodgrass said, "most of our students return to school to get a good job."

The way forward

"It's important to point out that the Utica is merely one of 30 potentially productive formations in the state of Ohio," Reda said. Ohio has seen many changes in the early phase of Utica development. The majority of the areas now being drilled are not unfamiliar with the advantages and problems associated with the boom/bust cycles of most natural resource development.

With a clear focus on early planning, consistent engagement with the industry, and working to see how to best adapt to oncoming rushes of population and opportunites, it is likely Ohio can build something that lasts. Enslin spoke on behalf of his experiences in Carroll County and with the coal industry prior to shale. "The best way for communities to find sustainability is to constantly ask what we want our communities to look like 10 years from now and encourage the way forward."