Strategic Development on the Outer Edge

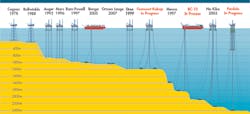

When Shell acquired the ultra-deepwater leases for Perdido in 1996, the technology to develop them didn’t exist. There were other notable deepwater developments, of course. Each had pushed the boundaries of technology, but in solving Perdido’s many technical challenges, Shell has opened new frontiers for oil and gas exploration.

The Perdido oil and gas development covers a portion of the geological formation known as the Perdido Fold Belt. The producing reservoirs lie within the Paleogene or Lower Tertiary zone, a portion of the Gulf of Mexico that has not been produced before. The seabed there resembles a small version of the Grand Canyon, including cliffs with near vertical drops of up to 1,000 feet.

The hub of the Perdido development is some 200 miles due south of Freeport Texas. The nearest neighbor is the Hoover-Diana platform, about 60 miles to the north. Shell began 3D seismic surveys on Perdido in 1998. The discovery well was completed in 2002. Development drilling began in 2007 and is scheduled to continue through 2016.

“There is a lot of courage in this story,” says Bill Townsley, Perdido venture manager. “We purchased the Perdido leases in up to 10,000 feet of water at a time when the industry’s capability was barely 3,000 feet. One of our satellite wellheads will be installed at 9,627 feet.”

A workable plan

“I joined the project in January of 2005,” says Dale Snyder, Perdido project manager. “By the end of the year, we’d settled on a development concept and begun the front-end engineering and design.”

Engineers also had to design for the higher crushing pressures of depths greater than 9,000 feet, and other environmental forces such as storm-driven waves, hurricane-force winds and the Gulf of Mexico’s strong loop currents.

“The deeper you go, the bigger these structures get – unless you break the pattern,” Snyder says. “For Perdido, we also have reservoirs that are atypical for the Gulf of Mexico. Because of low reservoir pressures and the variety of our target zones, Perdido requires a lot of wells.”

There are up to 35 wells in the Perdido development plan. Twenty-two are directly under the spar. A conventional deepwater production system would require 22 risers with all their associated bulk and weight.

“Economically, we just couldn’t make that work,” Snyder says. “It is very expensive to solve the technical problems and operate things at extreme water depths. Beyond that, if you build a mammoth structure, the cost of construction becomes prohibitive. For Perdido, we wanted a new kind of deepwater platform, one that was light enough to be economical, yet big and sturdy enough to contain all the drilling and production equipment we needed to develop the field.”

The Perdido concept design team wanted a central platform with full drilling and production capability onboard. Before Perdido, the world’s deepest water depth for such a platform was 6,300 feet, but several emerging technologies, including direct vertical access to the wells (DVA) and a subsea boosting system allowed the engineering and design team to greatly reduce the size of the structure.

“We needed to be able to pump liquids from the seabed to the surface,” Snyder explains. “In shallower waters, that’s not a big issue, but when the water is a mile and a half deep, it takes a lot of pressure to move fluids up to the platform. Most new reservoirs have enough internal pressure to overcome the hydrostatic pressure above them and push fluids up the wellbore to the surface. Perdido’s reservoirs are relatively low pressure, so we needed a boosting system.”

The other significant challenge was the potential of forming hydrates – an icy mix of water and natural gas that can easily clog flowlines. The solution was to separate gas and liquids on the seabed, then let the subsea boosting system push them to the surface, each through different lines.

With that capability, the design team could comingle fluids from all the wells on the seafloor, before pumping it to the surface. It was part of the enabling technology. Instead of 22 production risers from 22 wells, they only needed five, and with just five risers, Perdido could be a much smaller platform.

Target Zero

From the beginning, the safety of the workforce was a critical design element for the engineering team. No project managers want to have injuries on the job, but the remoteness of the Perdido development presented some unique challenges.

“We started off in 2005 with the idea that Safety was the most important thing we would do on Perdido,” Snyder recalls. “We would get it right. We would be a world leader in safety, and we put tremendous effort into that.”

The design team named their safety program “Target Zero.” The core concept was that if you could convince someone to work safely for just one shift, then it was possible to do the entire project that way. In mid-November, 2009, Perdido reached the milestone of 10 million man hours without a lost-time injury. Even with the wide range of complex operations, high-risk activities and fabrication sites around the world, by the time Perdido reached first oil on March 31, 2010, there were still no known lost-time incidents.

“Of all our accomplishments,” Snyder says, “I am most proud of our safety performance. It shows the leadership and commitment of our teams to go after safety and make it the most important thing we do.”

A new frontier

“This is a whole new regime for the Gulf of Mexico,” Snyder says. “Not only have we paved the way by solving the biggest problems of an ultra-deepwater development, it is equally important that we’ve figured out how to produce from the Lower Tertiary. The whole industry is watching to see how we do, because many development companies see this as the next big opportunity.”

“While the project had its share of inevitable setbacks, the team’s response was outstanding, says Lisa Johnson, who was the decision executive during offshore instllation. “There was always a healthy balance of support and challenge throughout the team, as well as with our Perdido partners.”

Particularly effective was an all-team meeting with the Perdido contractors. Held early in the project, it allowed everyone involved to review various aspects of their work and to identify anyBill Townsley, Perdido Development venture manager

Building on a strong partnership

“I’ve dealt with a lot of partnerships in my career,” says Bill Townsley, Perdido Development venture manager. “The deepwater environment is no place to be arrogant about your skills. We have two experienced partners on this project, so one of the things we’ve done is to be very open and transparent with our design and planning. The cooperation between partners has helped to keep us on track and deliver this project on time.”