MTBE latest victim of US environmental overregulation?

The current efforts in the US to ban the use of the gasoline oxygenate methyl tertiary butyl ether underscores how overzealous and wrong-headed enforcement of US environmental regulations continues to damage the country's economy.

By 1990, direct compliance costs and productivity growth-inhibiting effects from environmental regulations had taken a bite out of US economic growth.

Real gross domestic product probably could have been 20.65% higher than the US actually attained by that time (see chart and Marxsen, 2000, p. 76).

Today, environmental regulations are giving the US an even larger and still-growing cumulative shortfall in real GDP growth. A command-and-control regulatory approach dominates environmental policy and is often driven by inordinate preoccupation with insignificant risks and an almost complete disregard for the costs imposed by the bizarre edicts that it imposes.

The recent controversy emanating from the discovery of MTBE in the nation's drinking water provides one relatively small example of the often-foolish extremism in the name of the environment that has contributed substantially to 25 years of US wage stagnation.

Litigation's role

Litigation plays a large role in US environmental regulation. The city of Santa Monica, Calif., last year filed suit against 18 oil companies for damages possibly exceeding $200 million. The firms allegedly polluted city drinking-water wells by blending MTBE in the gasoline they sold.

The $200 million would presumably cover cleanup and litigation costs and was based on a US Environmental Protection Agency estimate of the cost of removing the MTBE from the city's drinking-water wells. Santa Monica Mayor Ken Genser claimed that the city could no longer use most of its wells for drinking water-wells that had been used for decades.

A Canadian company, Methanex Corp., recently sued the US under the aegis of the North American Free Trade Agreement because California approved a phased ban of MTBE in response to finding groundwater contamination. The California ban takes effect as of 2003, and the Vancouver, BC-based firm is seeking $970 million in damages. (MTBE is made from methanol, and Methanex is a major producer of methanol).

International agreements have long attempted to resist tariffs and quotas, and so protectionist tactics have shifted to using regulations instead. Now, multilateral bodies such as the World Trade Organization and newly formed international courts are changing the global legal environment. NAFTA includes provisions enabling foreign investors to sue national governments if expectations of future profits are nullified by federal, state, or local policies. Because California's MTBE ban is not really defensible on public health grounds, Methanex perceives an arbitrary taking. Perhaps California finds a truth-based defense prohibitively embarrassing, because its behavior is not protectionist but merely phobic.

Florida resident Paul Douglas Young has filed what may be the first MTBE class action lawsuit in Temple Terrace, Fla. Seeking to include all Floridians living within 2,000 ft of an ExxonMobil Corp. station, Young claims that MTBE seeped into his wells. He is hitting ExxonMobil with a "toxic trespass and nuisance" lawsuit. People in Illinois, New York, and California have filed similar lawsuits in their own localities.

Such legal efforts are put forth in the name of community action in the defense of environmental values. And juries grappling with subtle issues of science in such matters are often swayed by expert witnesses who may be more skilled in the art of persuasion through selective presentation than they are conscientious in the use of sound science.

Local officials are sensitive to the broader casual opinion of the public, misinformed though it may be. State officials discovered MTBE in three Nebraska municipalities' water systems. The chemical was found in wells in Hyannis, Scribner, and Ruskin during routine tests for volatile organic chemicals. The amounts were near or slightly above the laboratory-reporting limit (nearly the smallest amounts detectable by modern science) and posed no danger to public health. The insignificance of the risk, however, did not dissuade Hyannis from quitting pumping one of its four municipal wells in July and from searching for a place to sink a new well, at a cost approaching $300,000. Investigating a well site costs $5,000-10,000, and the cost is paid for by the person or company that owned the property when the contamination occurred. Fearing political repercussions, the state subsequently hired contractors to do basic tests on 2,100 leaking underground gasoline tanks, most of which have never been investigated for contamination.

MTBE survival, history

How can MTBE survive the lynch-mob mentality that now pervades US environmental politics? Those knowledgeable and interested enough to defend such a chemical find themselves overwhelmingly attacked for their profit motives. On the other hand, environmentalists' motives often seem pure because they are couched in idealistic terms.

In early October 2000, an 11-6 majority of the US Senate environmental and public works committee recommended a ban on MTBE as a gasoline additive beginning in 2005.

The irony here is that MTBE's popularity as a gasoline additive stems directly from congressional mandates to increase the oxygen content of gasoline to enhance its combustion and thus reduce certain harmful emissions in order to improve the nation's air quality.

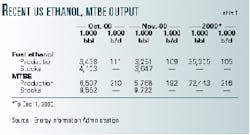

When President George Bush signed the Clean Air Act Amendments of 1990, areas in the US with the worst air quality were required to switch to reformulated gasoline (RFG) containing an oxygenate. In a practical sense-given the potential volumes entailed (Table 1)-refiners had just two choices: costly ethanol or cheaper MTBE.

Ethanol is not practical outside the Corn Belt states of the upper Midwest. Because of its affinity for water, ethanol already blended into gasoline makes it unsuitable for transporting through pipelines; and trucks must therefore transport it to refineries as blendstock. Even the fairly widespread use of ethanol in the upper Midwest owes to the fuel's subsidized status-it receives a tax credit of 54¢/gal. Without the tax credit, the additive could not remotely begin to compete with other, petroleum-based fuel additives.

Given the logisitical and economic problems associated with ethanol, most refiners chose MTBE as an oxygenate. Before the legislation requiring the use of oxygenates was implemented, small amounts of the then little-known MTBE were already being used to boost octane. Soon, gasoline all over the US was being blended with MTBE largely because it was well established within the existing refining and distribution system.

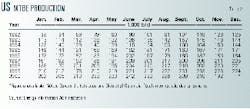

By the end of last year, billions of gallons of MTBE were being produced annually in the US, ranking it as one of the nation's most widely produced chemicals (Table 2).

MTBE in groundwater

A trace of MTBE in groundwater today is hardly a terrible surprise. For years, oil industry scientists, government regulators, and environmental engineers were predicting that MTBE would get into groundwater. In 1980, the CBS news magazine 60 Minutes reported that MTBE was first detected near a Shell Oil Co. service station in Rockaway, NJ. The late 1980s found dozens of sites in Maine contaminated with MTBE. Peter Garrett and two of his colleagues at the Maine Department of Environmental Protection warned the American Petroleum Institute, the National Well Water Association, and the EPA of the threat. The three colleagues recommended that MTBE either be banned outright or special precautions be used in its storage. They had found that, of all gasoline contaminants, MTBE moved the fastest and the farthest in groundwater and was the most difficult gasoline contaminant to clean up.

Clearly, it was only after it was first reported to be a groundwater threat that MTBE was effectively mandated as a gasoline additive. Recent progress toward banning it comes more from evolving political processes than from new scientific discoveries.

The source of nearly all MTBE groundwater contamination has been leaking underground storage tanks (LUSTs), a problem subsequently corrected in the 1990s. Ironically, about 1.25 million underground fuel tanks had been closed down by EPA's December 1998 deadline for meeting mandated leakproof specifications. A smaller number actually met the new specifications by that time-891,686 to be exact-partly because the average upgrade cost about $100,000.

In retrospect, the costly effort seems extravagant. A mid-1990s report from Lawrence Livermore National Laboratories and a consortium of California universities indicates that bacteria native to the soil soon destroy most of the constituents of gasoline that leaks from underground storage tanks. As luck would have it, MTBE appears to be virtually the only exception, being relatively inert biologically. The government, by essentially forcing the addition of most MTBE into the nation's gasoline supply in the first place, then established the need for leak-proofing fuel tanks.

Now that the LUST problem has been corrected, MTBE added to motor fuel ceases to contribute significantly to groundwater contamination. California has been one of the largest users of MTBE in the US. SRI Consulting, a unit of Menlo Park, Calif.-based SRI International Inc., argues that most of the "costs" appearing there in the form of damage to drinking water sources are actually "sunk costs." Well-water contamination lags leakage from nearby fuel tanks because MTBE moves underground no faster than the very slowly flowing groundwater itself. Most of the MTBE now showing up in California wells originally came from LUSTs long since either shut down or upgraded to prevent further leaking. In effect, the California MTBE ban remedies a problem that has already been solved.

MTBE health risk

Former EPA Administrator Carol Browner created a special blue-ribbon panel in 1998 to investigate concerns about oxygenates in gasoline. This panel reported that 5-10% of communities in areas using MTBE in gasoline have found detectable amounts of MTBE in community drinking water. EPA's limit for MTBE in drinking water is 20-40 ppb. Only about 1% of these detections have shown levels of MTBE above 20 ppb.

In the US, the average person consumes about 1 quart/day of water (in addition to another 1.5 quarts ingested in foods and drinks) and lives about 75 years. A quart of water per day for 75 years means the average person drinks about 27,375 quarts of water in a lifetime. At 20 ppb, a person's lifetime consumption of MTBE would be 0.01752 oz. If this lifetime quantity of MTBE were added all at once to a dry martini, an informed college student would probably drink it on a dare and suffer no harm.

Jack Snyder, a professor of toxicology at Thomas Jefferson University, has testified before the New Jersey state government that, "From a scientific and medical perspective, there is no basis for the contention that exposure to MTBE causes objectively verifiable human health effects."

Snyder has emphasized that, from a health effects standpoint, MTBE is no different from ethanol. Indeed, medical doctors are familiar with the substance. MTBE is an established internal medicine administered to humans full strength and in substantial quantities.

An article in The New England Journal of Medicine reports that gallstones are dissolved within minutes to hours by infusing MTBE into the gallbladder. The same article reports that 72 out of 75 patients experienced more than 95% dissolution of their gallstones when treated with MTBE over a period of 1-3 days. Lawyers testified in Methanex's NAFTA case hearing that "despite single doses of up to 20 ml, and significantly larger doses being administered over a period of days via catheter for direct infusion into the gallbladder, no consistent acute or chronic toxic sequelae have been reported, other than varying intensity of nausea and the detection of a breath odor." Interestingly, 20 ml is about 0.68 ounces, or roughly 39 times the amount a person would ingest in a lifetime of drinking water daily from one of the most MTBE-polluted wells in the US.

A report on the effects of MTBE that is available from the web site of the University of California-Davis tells about measured MTBE in fatty tissues from the abdominal wall in nine patients undergoing MTBE therapy for dissolution of gallstones. Such fatty tissue contained 18-303 ppb of MTBE, with a mean of 135 ppb. In other words, levels of MTBE in body tissues were orders of magnitude higher than the amounts found in the drinking water from 99% of the contaminated wells in the US. Froines, et. al., reported that MTBE has "generally been well tolerated" by a large number of patients and that only a few gallstone patients treated with MTBE suffered symptoms such as nausea or central nervous and respiratory depression.

Scientists have been endeavoring to determine MTBE's toxic properties and their effects on people in small concentrations through air and water for over 10 years. While MTBE can, like most chemicals, injure people when consumed in extremely high doses, laboratory animals must receive thousands of times the amounts of MTBE to result in illness than humans could possibly ingest through water contamination.

Sensitive people can smell MTBE when its levels are 2 ppb, the equivalent of two drops in a swimming pool; they can taste MTBE at 2.5 ppb. The public has understandably been concerned about studies showing rodents getting cancer after exposure to huge amounts of MTBE over their lifetimes. However, additional studies are strongly suggesting that the particular cancer-afflicted rodents are unusual animals having a special susceptibility not found in humans at all. Studies show that MTBE is not the kind of chemical that damages fetuses, causes infertility, or does harm to genetic structures of cells.

The EPA simply leaves open the possibility of cancer risk from long-term exposure to MTBE but mostly objects to it on the grounds that it makes water smell a little like paint thinner. A 1993 EPA report showed that adults who were exposed to high levels of pure MTBE exhibited no health symptoms. Nevertheless, EPA has forced oil companies to subsidize replacement water for a number of communities affected by tiny traces of MTBE in their water systems.

Before her departure with the rest of the administration of President Bill Clinton, EPA Administrator Browner urged Congress to encourage the use of ethanol in particular and renewable fuels and additives in general. MTBE, mostly made from natural gas, is not considered "renewable," as is politically correct ethanol.

MTBE a 'nocebo?'

Media reports suggesting health effects seem clearly mistaken. MTBE qualifies as what commentator Michael Fumento has termed a "nocebo," essentially the opposite of a placebo.

A placebo is a sugar pill that makes patients think they feel better while a nocebo is a harmless substance that makes people think they feel bad.

Fumento relates the account of a librarian in a new building who was told that the library's bookshelves contained formaldehyde. Shortly afterwards, she started suffering the classic psychosomatic symptoms of difficult breathing, painful joints, and headaches. When told that the information was incorrect, her symptoms disappeared. She remained free of symptoms, blissfully unaware that the bookshelves turned out to contain formaldehyde after all.

In this regard, it is interesting to see how reports of symptoms related to MTBE vary across the US. Reports of symptoms plummeted in Alaska after the MTBE ban there was announced. When the same RFG formula was used in Milwaukee and in Chicago during 1996, many Milwaukee residents complained of symptoms, but there were no complaints registered from Chicago residents.

MTBE health benefits

What is missing from much of the debate over MTBE's health risks is a consideration of the intended health benefits that MTBE use confers.

SRI concluded that very considerable MTBE-spawned reductions in California air pollution have been largely ignored in assessing the benefits of MTBE.

As for public health concerns, SRI stated: "The health risks of using MTBE in gasoline appear to be relatively small and are comparable to or less than the health risks posed by unleaded gasoline without MTBE." SRI found that the California ban on MTBE is not supportable based on public health concerns.

According to the Oxygenated Fuels Association, MTBE's health benefits outweigh its risks. MTBE reduces the amount of emissions of benzene and other carcinogenic compounds released in the combustion of gasoline. In a study modeling the risk of cancer, a 13% lower rate of cancer was attributed to blending MTBE with summertime gasoline and a 20% lower rate of cancer attributed to blending MTBE with wintertime gasoline.

Clean fuels costs

Critics of the original 1990 Clean Air Act amendments warned that the "clean fuels" provisions would require the US refining industry to spend $37 billion, measured in 1990 dollars, in related capital outlays over the course of the 1990s. The same critics warned that consumers would be spending an extra $18 billion/year by 2000 to purchase the "clean fuels" as prescribed by law.

In mid-1998, the US secretary of energy requested that his industry advisory panel, the National Petroleum Council, estimate the cost of eliminating MTBE from gasoline. NPC recently reported that the cost would include an investment of $1.4-10 billion, with the upper limit representing replacing MTBE with ethanol gallon for gallon. Losses associated with diminishing the value of existing equipment seemed totally ignored.

Like military conscription, an MTBE ban imposes inordinate burdens on a minority consisting of unlucky persons and groups. Glennville, Calif., for example, is now a ghost town as a result of the town's one service station being closed down because of MTBE groundwater contamination. At one time, downtown Glenville was a popular location where tourists stopped for meals on their way to Death Valley and where ranchers gathered socially. Everything changed for this town of 300 people when the State Water Board called a town meeting in August 1997, telling residents not to consume tap water anymore. Subsequently, with people no longer stopping for gasoline, the once popular Grizzly's Café closed despite endeavors to remain open by using bottled water. Other Glenville businesses folded in the wake of the gas station closure. Residents complained of being unable to sell their houses; banks ceased lending money.

Action against MTBE would also be strongly felt along the Texas Gulf Coast area of Houston-Beaumont. With 14 MTBE plants, this area houses more MTBE facilities than any other place in the world. Shaky from the beginning-because of the cyclical nature of the petrochemical business-the whole $3 billion/year MTBE industry could get the kiss of death from the water contamination issue. Another Texas casualty would be the methanol industry that supplies the MTBE plants-the Houston-Beaumont area alone houses six methanol facilities. A 1999 Houston Chronicle article stated that 25,000 jobs along the Texas Gulf Coast were directly and indirectly derived from the combination of MTBE and methanol industries.

Cost of compliance

Environmental regulations in general have resulted in considerable "compliance costs." Much equipment is purchased or fabricated to comply with specifications dictated by government bureaucrats. Much labor is expended and materials are purchased. But compliance costs aren't even half of what America's command-and-control approach has squandered in terms of lost output. Productivity has been greatly affected. For every dollar of compliance costs, America suffers additional costs of $3-4 in terms of lost efficiency and output. The creative, productivity-enhancing efforts of many individuals have been constrained. The efforts and imaginations of industry's inventive people have been diverted to the great compliance effort and away from efforts to produce better products in greater abundance. The nation has been drifting from a land of liberty to a land of mandates and bureaucratic oppressors. A marked slowdown in American productivity growth coincided with the passage of the major environmental laws in the early 1970s.

Does US environmental regulation at least bring substantial improvement to the quality of the environment that most Americans cherish as priceless? Irrational and hysterical regulatory flip-flops such as those regarding the use of MTBE as a fuel oxygenate perhaps illustrate more-pervasive shortcomings of the environmental protection movement.

The public was willing to make great sacrifices for the sake of the environment, and the advocates of bureaucratic fiat have been eager to oblige this willingness. Yet one must feel a little like the members of some primitive society that casts its fairest maidens into the volcano every year to appease a demanding earth god.

The clean air and clean water acts of the early 1970s coincided with a perplexing national slowdown in productivity growth. Thereafter, America entered a quarter-century era of wage stagnation, and the negative effects fell harder on the lower wage segments of the labor force. The MTBE saga is but a small illustration of one of the most pervasive mechanisms of a modern American growth dysfunction.

Bibliography

Bonem, Mike; Cvitkovic, Emilio; Golden, David; Malhotra, Ripudaman; Mirsalis, Jon; McMillen, Don; Mills, Ted; Pavone, Tony; Rahman, Rezal and Smith, Ron. A Review and Evaluation; of the University of California's Report, Health and Environmental Assessment of MTBE. SRI Consulting (SRIC) and SRI International, 1999. http://www.ofa.net/SRIC-MTBE-report-FINAL.htm.

Froines, John R.; Collins, Michael; Fanning, Elinor; McConnell, Rob; Robbins, Wendie; Silver, Ken; Kun, Heather; Mutialu, Rajan; Okoji, Russell; Taber, Robert; Tareen, Naureen; and Zandonella, Catherine. An Evaluation of the Scientific Peer-Reviewed Research and Literature on the Human Health Effects of MTBE, its Metabolites, Combustion Products and Substitute Compounds, 1998. Contributions from The Center for Occupational and Environmental Health USC-UCLA Southern California Environmental Health Sciences Center, and the UCLA School of Public Health, University of California at Berkeley School of Public Health. http://tsrtp.ucdavis.edu/mtberpt/vol2.pdf.

Ivanovich, David. "Fuel Additive Uproar Could Hurt Gulf Coast; Smog-Fighting MTBE Infiltrating Water Wells," Houston Chronicle, June 13, 1999.

Kroft, Steve. MTBE: "Gasoline Additive Used by Oil Companies to Meet Requirements of Clean Air Act Is Now Polluting the Groundwater," 60 Minutes, Jan. 16, 2000. CBS News Transcripts.

Marxsen, Craig S. "Costs of Remediating Underground Storage Tank Leaks Exceed Benefits" (OGJ, Aug. 9, 1999, p. 21).

Marxsen, Craig S. "Why Stagnation?" B>Quest, 1999. http://www.westga.edu/~bquest/1999/stag.html.

Marxsen, Craig S. "The Environmental Propaganda Agency." Independent Review 5:1 (summer 2000): 65-80. Available from Infotrac Galegroup http://web6.infotrac.galegroup.com/itw/infomark/839/605/16107356w3/purl=rc1_EAIM_0_A64148825&dyn=5!ar_fmt?sw_aep=unl_eai.

Oxygenated Fuels Association. "MTBE: Health Benefits vs. Health Risks." (June 1999). http://www.ofa.net/MTBE-HealthBenefitsvsHealthRisks.htm.

Schweke, William and Stumber, Robert. "The Emerging Global Constitution: Why Local Governments Could Be Left Out," Public Management, January 2000. Available from Infotrac Galegroup: Magazine Collection 102E2685; Electronic Collection A58836305; RN A58836305.

Thistle, Johnson L.; May, Gerald R.; Bender, Claire E.; Williams, Hugh J.; LeRoy, Andrew J.; Nelson, Peter E.; Peine, Craig J.; Petersen, Bret T.; and McCullough, J. Edward, 1989, "Dissolution Of Cholesterol Gallbladder Stones By Methyl Tert-Butyl Ether Administered by Percutaneous Transhepatic Catheter," The New England Journal of Medicine 320:10, (March 9, 1989): 633(7). Available from Infotrac Galegroup, http://web6.infotrac.galegroup.com.

US Environmental Protection Agency, Achieving Clean Air and Clean Water: The Report of the Blue Ribbon Panel on Oxygenates in Gasoline, EPA420-R-99-021 (Sept. 15, 1999). http://www.epa.gov/oar/caaac/r99021.pdf.

Williams, Bob, 1995. "MTBE, Ethanol Advocates' Squabble May Complicate RFG Implementation" (OGJ, Feb. 13, 1995, p. 17).

The author

Craig S. Marxsen is associate professor of economics at the University of Nebraska at Kearney, Neb. His doctoral dissertation, completed in 1976, focused on the influence of interest and inflation on fuels supply. Marxsen previously published an article in Oil & Gas Journal that was an analysis of how the costs of remediating underground storage tank leaks exceed the benefits (OGJ, Aug. 9, 1999, p. 21).