China's refining sector challenges: surging demand, rising imports of sour crudes, new business models

China ranks second in total primary commercial energy consumption after the US and third in total primary commercial energy production after the US and Russia.

In 1999, China consumed 16.5 million boe/d of primary energy, consisting of 69.5% coal, 25.0% oil, 2.9% natural gas, 2.1% hydropower, and 0.5% nuclear power. Despite its dominance in China's primary energy mix, coal consumption and production have declined significantly since 1996. For instance, the coal production of a little over 1 billion tonnes in 1999 was 25% lower than the peak production of 1.4 billion tonnes in 1996.

China's oil industry plays an important role in China's national economy and social development. It is a giant industry in terms of international standards, ranking fifth in the world in terms of crude oil production (after the US, Saudi Arabia, Russia, and Iran) and third in consumption of petroleum products (after the US and Japan).

With nearly 5.6 million b/d of crude oil refining capacity at the end of 2000, China is now the largest refiner in Asia. Its refining capacity also ranks third in the world after the US and Russia. Over the past 5 decades, China's downstream oil industry has gone through a tortuous road to modernization. While China should be proud of her achievements in this sector, there are many challenges ahead as we enter the 21st century.

Refining sector structure

China has a large refining industry with a fairly long history of indigenous technology development.

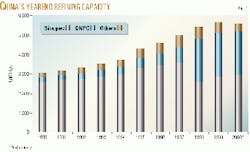

Total refining capacity has risen spectacularly, from almost nothing in the early 1950s to 285,000 b/d in 1965, 1.4 million b/d in 1975, 1.9 million b/d in 1980, 3.1 million b/d in 1990, and 5.64 million b/d at the end of 1999, before it finally came down to 5.59 million b/d by the end of 2000 following the crackdown on small refineries.

China's refining industry has under- gone numerous changes; the most important of these recently was the 1998 reorganization. Upon the completion of the reorganization in July 1998, two integrated oil companies, China National Petroleum Corp. (CNPC) and China Petrochemical Corp. (Sinopec), were reborn. The interests and assets of CNPC and Sinopec have been divided along geographical lines.1

The restructuring of CNPC and Sinopec has redefined the ownership structure of the refining sector. As it now stands, China is estimated to have a total refining capacity of 5.59 million b/d at the end of 2000. Of the total, Sinopec accounted for 53% and CNPC 40%, while all other refineries accounted for a total of 7%. In 1997, right before the reorganization, Sinopec had 72% of total refining capacity, CNPC 16%, and the rest 8% (Fig. 1).

One problem with the data for refining capacity in China is the fact that part of the capacity data is estimated and therefore not always accurate. That is due to the issue of small refineries, which until the 1998 reorganization were predominantly owned by local authorities. The situation was particularly confusing before 1998, but the information has become a little more clear since 1999 and especially in 2000, after a high-profile crackdown on small refineries led by the State Economic and Trade Commission.

As a result of the reorganization, the upstream oil sector is divided among CNPC, Sinopec, and China National Offshore Oil Corp. (CNOOC), with the dominant role played by CNPC. A significantly larger part of the downstream oil sector, however, is in the areas under Sinopec. The imbalance between CNPC and Sinopec-and the need for Sinopec to buy CNPC crudes and for CNPC to sell its products to Sinopec markets-have proved to be very challenging for the two giant state oil companies to deal with, especially when competition and efficiency improvements were cited as the major reasons for the 1998 oil industry restructuring. In other words, efforts to maintain smooth supply of crudes and products between the two state oil companies and to promote competition are extremely difficult, if not totally impossible.

In the trading area, exports and imports of crude oil and major refined products, such as gasoline, diesel, jet fuel, and to a lesser extent, fuel oil, are monopolized by three state oil companies: United International Petroleum & Chemicals Co. Ltd. (Unipec), China National United Oil Corp. (Chinaoil), and China National Chemical Import & Export Corp. (Sinochem). Although Unipec and Chinaoil are joint ventures with Sinochem, they are mainly controlled by Sinopec and CNPC and eventually the latter's own trading arms. While Sinochem continues to conduct oil trade business, its share of oil will be shrinking further in the near future.

In 1999 and 2000, all three Chinese state oil companies formed full-fledged stock companies for the purpose of domestic and overseas stock listing. PetroChina was established by CNPC in November 1999, while Sinopec formed Sinopec Ltd. in February 2000. Prior to that, CNOOC established its listed company, CNOOC Ltd., in 1999. PetroChina raised $3.1 billion through an overseas initial public offering in April 2000, while the debut of Sinopec Ltd.'s IPO in October 2000 netted the company $3.7 billion. CNOOC, whose stock listing in October 1999 was not successful, is targeting February 2001 or later for its IPO.

Processing configurations, utilization

China's refining industry has several distinguishing characteristics.

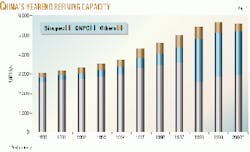

First, it boasts a significant amount of cracking capacity which, at 44% of the crude distillation unit (CDU) capacity, is more than twice the share in Japan and much higher than the Asia-Pacific region average but lower than the share in the US (see table).

The high cracking-CDU ratio is attributable to the country's long history of using mainly domestic crudes, which are heavy and waxy with high pour points, as refinery feedstock. Of the cracking facilities, however, fluid catalytic cracking and resid catalytic cracking far outweigh the others.

The second characteristic of China's refinery configuration is that the share of its cat reforming in total CDU capacity (6.1% at the end of 1999) is far lower than the shares of cat reformers in Japan (14.5%) and the US (21.3%). China's low reforming-CDU ratio is partly due to the country's historical crude slate, of which the naphtha yield is low and insufficient to support a large reformer capacity. However, the 1999 ratio of 6.1% was significantly higher than 3.9% in 1995.

Third, the utilization rate of China's refining capacity has historically been low. Prior to 1986, the government's policy of maximizing oil exports reduced the availability of feedstock to the domestic refining industry. Although more crude oil was diverted to domestic refineries thereafter, declining crude production, rapid expansion of the refining capacity, and the continued existence of small and very small refineries have kept utilization rates low.

Finally, although China has enough capability to deal with heavy crude oil, most of its refining facilities are all equipped to run only low-sulfur oil, except for a few new and revamped units in the coastal refineries.

This is in contrast with refineries in Japan, Taiwan, and South Korea, which have substantially higher capability for running high-sulfur Middle East crudes. China has made major efforts to change the situation, which is discussed later in this article.

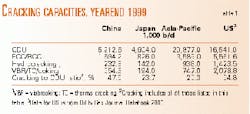

Refining utilization rates are closely related to crude runs, which have been growing vigorously in China-but also unevenly from year to year-since the beginning of the 1990s. In 1999, crude runs reached 3.67 million b/d. Crudes runs are estimated to have jumped to nearly 4.2 million b/d in 2000 (Fig. 2).

The changing utilization rate of the Chinese refineries is shown in Fig. 3. In 1998, the overall refinery utilization rate was only 61%. The situation started to improve in 1999, when the utilization rate increased to 65%.

The rate since then is estimated to have further increased to 75%, the highest since the beginning of the 1990s. The high 2000 rate was mainly caused by the surge of crude runs. The closure of small refineries has also contributed significantly to the increase in utilization rate.

Handling sour crudes

With a few exceptions, such as crudes from Oman, Yemen, and part of Abu Dhabi, Middle East crudes all have a high-sulfur content, while most of China's refineries, until recently, were unable to process such crudes.

China has been quietly preparing to deal with the issue of importing sour crudes for years. In the mid-1990s, in anticipation of rising Middle East oil imports, Sinopec started the long process of revamping, upgrading, and expanding its refineries to add sour crude processing capabilities. Sinopec's original plan was to have close to 1 million b/d of processing capacity that can handle imported sour crudes by 2000.

As of today, efforts have fallen short of this target, but the country has managed to establish 700,000 b/d of processing capacity for sour crudes. For crudes with sulfur content of 1.5% and higher, the current processing capacity for China is 560,000 b/d.

In addition to revamping and upgrading crude distillation units as a major way for China to handle the rising imports of Middle East sour crudes, upgrading, revamping and expansion of certain secondary processing units are also planned. Among them, hydrotreating and, to a lesser extent, hydrocracking are being singled out for further treatment and processing of high-sulfur yield from the crude distillation towers. At the end of 1999, China had 578,000 b/d of hydrotreating capacity, up from 209,000 b/d in 1992 (Fig. 4).

While it is expensive to build hydrocrackers, China has managed to increase its hydrocracking capacity by 40% from 1996 to the end of 1999.

Currently, China has 233,000 b/d of hydrocracking capacity, the highest in Asia.

In dealing with sour crudes, it appears that vacuum resid desulfurization (VRDS) has not been vigorously pursued in China. One reason is that China has a huge cracking capability, and the overall fuel oil production is low. Another reason is that there is still lack of stringent standards for producing and using low-sulfur fuel oil in China. Currently, China has only three VRDS units, totaling 98,000 b/d of capacity.

In addition to its VRDS unit, the Qilu refinery has recently added 28,000 b/d of atmospheric resid desulfurization (ARDS) capacity.

As long as China does not plan to massively export low-sulfur fuel oil, the incentives for building expensive VRDS or ARDS units are just not there. Given China's high demand for fuel oil and low domestic production of it, the situation for massive exports of fuel oil is unlikely to arise in the near future. However, over the long term, China may have to add resid desulfurization facilities to control the sulfur content in fuel oil.

Product demand, oil trade

Petroleum product demand in China is characterized by spectacular growth-especially since the early 1990s-and a radical transformation of the demand pattern, i.e., the lightening of the demand barrel. Fig. 5 illustrates the historical and projected product demand in China from 1985 to 2015.

Second largest in the Asia-Pacific region after Japan, China's petroleum product demand of 4.1 million b/d in 1999-including direct use of crude oil by industrial sectors and for power generation-constituted about 21% of total Asia-Pacific product demand. Demand in China is estimated to have jumped to 4.4 million b/d for 2000.

Petroleum product demand growth in China has not been smooth during the 1980s and 1990s. China witnessed a decline of oil consumption twice during this period: once in 1981 and again in 1990.

Both declines followed an overheating of the economy and resulted from retrenchment programs imposed by the government.

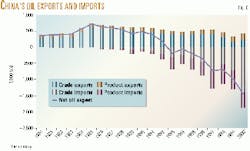

Throughout the 1980s, China was a net oil exporter. The net oil exports (crude and products combined) peaked in 1985 at 708,000 b/d.

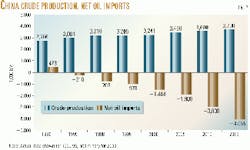

China's oil surplus has since been shrinking. In 1993, China became a net oil importer for the first time since the early 1970s. Net oil imports increased from 200,000 b/d in 1993 to 219,000 b/d in 1995, 736,000 b/d in 1997, and 978,000 b/d in 1999. In 2000, China's net oil imports (again including crude oil and refined products) reached an all-time high of 1.46 million b/d (Fig. 6).

The outlook to 2015

In the long term, expansion and revamping of the refining industry are still needed in China. This is not because China does not have enough capacity. In fact, China's current refining capacity exceeds its petroleum product consumption by over 1 million b/d.

The need for revamping, upgrading, and expansion is due mainly to the projected rise in the use of sour crudes from the Middle East. In 2000, China imported 725,000 b/d of crude oil from the Middle East. Our projections show that imports of Middle Eastern crudes will rise to 1 million b/d in 2005, 1.6 million b/d in 2010, and 2.1 million b/d by 2015.

China's efforts for increasing sour crude handling capability are continuing. By 2005, the plans of CNPC and Sinopec call for the construction of about 700,000 b/d of additional capacity that can handle sour crudes.

If all these plans are completed, China is expected to have 1.4 million b/d of capacity, of which 1.1 million b/d will be for typical sour crudes with 1.5% sulfur content or higher.

With continuous merging and shutting down of small refineries, it is expected that China's overall refining capacity will increase to 6.2 million b/d at the end of 2005, up from 5.6 million at the end of 2000. Projects beyond 2005 are speculative. Under our base-case scenario forecast, the total crude distillation capacity for the country is projected to further increase to 7.2 million b/d by the end of 2010 and to 7.8 million b/d by the end of 2015.

On the consumption side, China's petroleum product demand growth is expected to remain robust. Under the base-case scenario, China's overall petroleum product demand, including direct use of crude oil, is forecast to increase from 4.4 million b/d in 2000 to 5.4 million b/d by 2005, 6.4 million b/d by 2010, and 7.5 million b/d by 2015. As such, China is expected to add about 3.1 million b/d to its total product demand from 2000 to 2015.

On the refinery production side, overall refinery output will continue to increase as the Chinese refineries are likely to process more crude oil. Our base-case assumption is that China will process 4.9 million b/d of crude oil in 2005, 5.6 million b/d in 2010, and 6.5 million b/d in 2015.

Because of the expected vigorous refinery expansion, increasing crude runs, and rising refining utilization rates, net product imports into China through 2010 are forecast to be no more than 500,000 b/d but higher than 282,000 b/d in 2000. Net product imports could, however, go up to 900,000 b/d by 2015.

For oil as a whole, China's net oil imports, which are the difference between indigenous crude production and petroleum product demand, are expected to go up fast. Under the base-case scenario, it is expected that China's net oil imports will reach 1.9 million b/d in 2005, 3.0 million b/d by 2010, and 4.1 million b/d by 2015 (Fig. 7).

While the net imports include both crude and refined products, crude imports are expected to dominate the picture if the refining industry is successful in revamping and upgrading its sour crude handling capability and the crude distillation capacity in coastal areas as planned.

What's ahead

Under any scenario, China's overall oil imports are certain to rise over the next 10-15 years, because of sluggish growth in domestic oil production and strong growth in oil demand.

The Chinese state oil companies are taking serious steps to meet the growing demand by restructuring, revamping, and upgrading the country's refining system.

However, the bigger challenge for the downstream state oil industry is the forthcoming competition from foreign and private sector participants after China joins the World Trade Organization and further opens up its domestic oil industry and markets.

While some international majors are now partners of PetroChina and Sinopec Ltd., there is no guarantee that such business alliances will last forever. This is a new area for the state oil companies of China, which have to learn how to preserve the private shareholders' value and pursue long-term growth.

China also has to work hard to make sure its current multiple state-company system works, which is not easy-if not totally impossible, given the unstable nature of the system. As such, the refining expansion plans of Sinopec and CNPC may not be as economically attractive or prove to be feasible under free-market conditions.

China could therefore face a more precarious situation, in which large imports of both crude and refined products may be inevitable in order to satisfy the country's growing oil consumption.

Reference

- For a detailed discussion of the 1998 industry restructuring and its implications, see Fereidun Fesharaki and Kang Wu, "Revitalizing China's Petroleum Industry through Reorganization: Will It Work?" Oil & Gas Journal, Vol.96, No.32, Aug. 10, 1998. For more recent developments, also see "Restructuring of China's Oil Industry Continues as Doubts Regarding Its Success Loom," Oil & Gas Journal, Vol.98, No.1, Jan. 3, 2000.

The authors-

Kang Wu is a fellow at the East-West Center in Honolulu and the head of the center's China Energy Project. Wu's research interests and studies include energy economics, energy policies, energy market developments, downstream oil sector issues, and environmental impacts of fossil energy consumption with particular emphasis on oil and gas. He specializes in oil and gas sector issues in China and other countries in the Asia-Pacific region. Holding a PhD, Wu is the author or coauthor of many project reports, journal articles, conference papers, and other publications.

Fereidun Fesharaki is president and founder of FACTS Inc. Born in Iran, he received his PhD in economics from the University of Surrey in England. He then completed a visiting fellowship at Harvard University's Center for Middle Eastern studies. In the late 1970s, he attended the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries' ministerial conferences in his capacity as energy adviser to the prime minister of Iran. He joined the East-West Center in 1979 and currently is a senior fellow and head of the Energy Project at the East-West Center. Fesharaki's area of specialization is oil and gas market analysis and the downstream petroleum sector, with special emphasis on the Asia-Pacific region, Middle East, Latin America, and US. He is an advisor to numerous oil and gas and other energy companies, private and state-owned, and to governments in the Middle East, Pacific Basin, and Latin America, as well as to the US government.

This article is drawn in part from the upcoming multiclient study, entitled China's Downstream Oil Industry and Markets to 2015: Provincial and Regional Demand, Supply, and Balances, by FACTS Inc., February 2001.