Russian oil companies improve operational standards

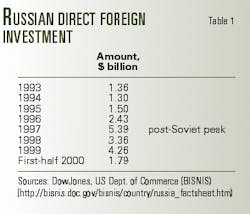

Russian oil companies continue to improve operational and financial efficiencies despite low levels of direct foreign investment (DFI, Table 1).

While higher oil prices have increased cash flow and relatively lower inflation rates have reduced costs, much of this success can be attributed to new organizational structures, the introduction of modern business practices, and an emphasis on technology management.1

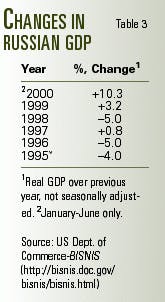

Partial proof can be seen in the audited financial statements of select companies OAO Lukoil, OAO Sibneft, and OAO Yukos whose 1999 return on assets improved by 13 percentage points, 6 percentage points, and 31 percentage points, respectively, over the previous year (Table 2).

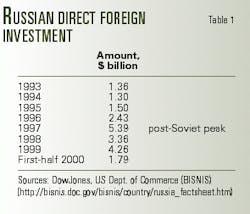

But more conclusively, it can be seen that aggregate output by the Russian producers has clearly risen for the first time in 11 years. In 2000, production broke a 5-year flat streak with output rising to 6.49 million bo/d, a 5.7% increase over 1999 (Fig. 1).

Russia in isolation

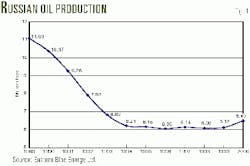

In 1997, direct foreign investment (DFI) doubled from the previous year to $5.39 billion, indicating a promising outlook for Western business interests. In August 1998, however, a series of global and domestic events resulted in a severe economic downturn and the subsequent devaluation of the ruble.2

Side effects of this "Russian Financial Crisis" included the termination of many foreign joint ventures and the bankruptcy of hundreds of Russian companies.

Yet in many ways, this economic setback may very well have had a positive impact on sustainable long-term growth. As the price of foreign imports skyrocketed, the typical citizen found that he or she could no longer afford European and American products. This in turn refocused demand back on Russian goods and services.

Consequently, Russian entrepreneurs proceeded to rebuild factories, agricultural enterprises, and service companies. The effects of this revitalization have in turn led to improved economic conditions (Table 3).

In contrast, FDI remains stuck at a fraction of other Eastern European countries. According to the Wall Street Journal "In Russia it's around $96 per capita, compared with $546 for Poland, and $1,166 for Hungary" (Dec. 5, 2000).

This very lack of Western interest may have prompted organizational changes seen in some of the major Russian oil companies today.

A Russian major

Sibneft, one of the top 20 companies in the world in terms of reserves (4.6 billion bbl), provides an example of how Russian oil majors are overcoming challenges associated with access to global capital, post-Soviet-era responsibilities, technology management, export pipeline issues, and ever-changing policies on the political front.

Created in 1995 through a loans-for-shares agreement proposed by Valdimir Potanin,3 Sibneft is a vertically integrated oil company with upstream, downstream, and marketing operations (Fig. 2).

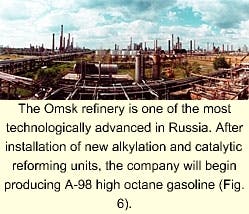

Its core upstream assets, managed by Noyabrskneftegas, are located near the city Noyarbsk in the Yamalo Nenetsky Autonomous Okrug. Downstream assets include the Omsk Oil Refinery, one of the most technically advanced facilities in Russia, and 720 retail outlets, of which 120 are operated by Omsknefteproduct.

A fourth operating subsidiary, Noyabrskneftegasgeophysica, conducts geophysical surveys (well logging) on wells owned by Noyabrskneftegas and Purneftegas, another Western Siberian oil company.

In 1999, Sibneft recorded net profits of $315 million on revenues of $1.75 billion (US GAAP).

Upstream

Sibneft had a lackluster year 2 years ago, a result of the Russian Financial Crisis, low oil prices, and an initial period of restructuring. But last year, the company grew its production faster than any other Russian company, with output rising 20% to 368,000 bo/d over a 12-month period. Average production for 2000 was 338,000 bo/d.

This surge in production was driven b an aggressive drilling program in 2000. During this time, drillers made 740,000 m of hole, more than twice as much in 1999.

By increasing upstream expenditures to $595 million, from $219 million in 2000, the company now aims to hike oil production another 11% to 375,000 bo/d by yearend.

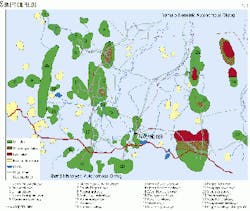

Sibneft holds licenses to 53 West Siberian oil fields of which 20 hold 4.6 billion bbl in proven reserves (Table 4, Fig. 3, map). More than 60% of the company's proven reserves are concentrated in five oilfields. Two of these, Sutorminskoye and Muravlenkskoye, generate about 40% of the company's production.

In 2000, Sibneft launched a $1 billion oilfield development program (Figs. 4 and 5), commencing production from four new fields: Romanovskoye, Yarainerskoye, East Vyngayakhinskoye, and East Pyakutinskoye (see Box-Horizontal Drilling). Additionally, new reservoirs were opened up in the mature Karamovskoye and Kraineye fields.

The company has also started drilling in the central area of the Sugmutskoye (Sugmut) field, which holds 965 million bbl of proven reserves. Last month, this field produced 62,000 bo/d. Peak production under a $64 million pilot project is expected to reach 40,000 bo/d in 2003, and full field development should produce at 135,000 bo/d by 2006.

Export markets

On average, Sibneft produces 35.8 API crude with a sulfur content of 0.58%. This compares with 31 degrees API for typical Siberian crudes, both of which are higher quality than other Russian grades.

Sibneft has partial access to two export lines, Novorossiysk and Tuapse, both on the Black Sea (Fig. 2). Crude sent to Novorossiysk consists of a blend of heavier Urals and lighter Siberian. The Tuapse line, on the other hand, is dedicated to "Siberian Light."

As a result, the Ural blend trades at a $1-3 discount to Brent, while Siberian Light receives a small premium. A new agency, the Khristenko Commission, regulates these lines, with two thirds distributed in proportion to production and the remainder allocated on a discretionary basis (see box, Pipelines for auction).

Unfortunately, Siberian crude transported to Novorossiysk does not rate a price differential even though it is a higher quality hydrocarbon.

Companies with higher-quality crudes have lobbied for compensation by proposing a "zero-sum" system. With this compensatory scheme, companies that produce heavier or sour crudes would compensate producers with above-average streams.

Ural producers, however, such as OAO Bashneft and OAO Tatneft, obviously oppose this scheme becasue they produce lower-quality crudes. If the government implements this system, Sibneft would generate additional cash flow in addition to its 23% share of Siberian Light currently exported to Tuapse.

Domestic markets

The domestic crude oil market is still quite limited because most oil moves directly from the wellhead straight to the export outlet or refinery without leaving the jurisdiction of the oil company. Thus, although the Russian crude oil system is no longer monopolized, for all practical purposes, it is now consists of a series of nationwide oligarchies.

Nevertheless, a domestic market has started to develop on two fronts. First, oil produced by joint ventures and production-sharing agreements (PSAs) sell their products both on the domestic and export markets, depending on contractual agreements and political factors.

Second, some companies, like Sibneft, have more refining capacity than upstream production. Thus, these companies often purchase crude oil from other producers on a "spot" market with prices set by the laws of supply and demand.

As more players enter new markets, and as competition grows, the price differential between global and domestic crude oil should begin to close.

A protege

The Russian Financial Crisis has affected Sibneft in a very major, yet positive way.

In 1997, Elf Aquitaine SA (now TotalFinaElf SA) and Sibneft entered into a preliminary work program that involved seismic evaluation and a development plan for the Sugmut field.

"We had been looking for foreign partners and Elf Aquitaine was the best candidate," Korsik told OGJ on a recent visit to Noyabrsk. "The idea was for Elf to buy a stake in Sibneft, then we would form a joint venture (JV) to develop Sugmut."

As a result, about 200 Western managers would have been incorporated into the Russian operation.

But economic conditions forced Elf to pull back from becoming a vested partner in 1998, although discussions continued on Sugmut. But after lengthy negotiations, neither party was able to agree on price.

Subsequently, Elf shut down its negotiations because it was unwilling to accept the currency risk associated with selling two thirds of its output on the domestic market.

This departure led to some soul searching for Sibneft.

"In 1999, when nobody was coming to Russia, we decided to look at alternatives and came to the conclusion that we must restructure along the lines of a Western oil company," Korsik said.

"We learned a lot from Elf. For example, we understood that all reservoir management-functions should be conducted inside the company, which is traditional for Western companies but not Russian."

Sibneft also saw that Western companies acquire expertise in drilling, fracing, and workovers from service companies outside the organization. Yet, a competitive market with a service-oriented infrastructure has yet to be developed in Russia leading to some very tough decisions.

"We wanted to create a market of services in Russia. But in the course of doing this, also had to get rid of our older services that would not fit within the new organizational model," said Korsik.

Soviet-era responsibilities

Sibneft, like other major Russian oil companies, has inherited Soviet-era infrastructure that includes enormous financial and social responsibilities. Unfortunately, in order for the company to become an efficient corporation in a market economy, with service companies competing for work based on price and quality, the company had to divest many services associated with construction, drilling, road building, and workover activities.

Similar to Western operators, Sibneft management feels it should be in the business of managing oilfield operations, not performing the services that go with them.

This dilemna, however, has not been easy to overcome for any of the Siberian majors (OGJ, June 14, 1999, p. 21).

During Soviet times, economic policy focused on the maximization of production (quotas) instead of the bottom line. "Towns like Noyabrsk were built with self-sufficient service capabilities," says Reval Mukhametzyanov, a Sibneft vice-president, "and like many township-forming enterprises (gradoobrazuyushie predpriyatiya), had to support the entire social infrastructure."

In the west, there are no analogies. Even oilfield towns like Midland, Tex., and Casper, Wyo., whose economies depend on the petroleum industry, have numerous operators and service companies that aggressively compete for work. "In Russia, services grew into monsters and companies became dependent on them," Mukhametzyanov added.

Nevertheless, Sibneft began removing these services from its balance sheet, initially turning them into independent business units that must learn to competing in the market place. To move the service subsidiaries in the right direction, Sibneft has set a threshold that governs when it is prepared to pay for services.

First, capital investments needed by services subsidiaries are regarded as loans. "This type of arrangement has led to a significant improvement in the maintenance of equipment," Korsik said.

Second, these service subsidiaries are allowed to provide service to outside parties. Noyabrsknefte- gazgeophysica (NNGP), for example, now works as a geophysical contractor to state-owned Rosneft in the Pur region, Lukoil in Kogalym, and Gazprom.

At the same time, Sibneft's service subsidiaries had to compete with other potential contractors, including foreign companies. "Even Sibneft's strategic alliance with Schlumberger is not immune to competition (see box, A strategic alliance)."

For example, the company employs BJ Services (Samotlar Fracmaster Services) and other French, American, Russian, and Canadian oil field service companies.

"There should be competition between Schlumberger, Halliburton, our internal units, and former units," Korsik noted. "If they [Russian subsidiaries] survive, then we will be happy. Perhaps they will find their own niche with less sophisticated and inexpensive technologies."

In many cases, Sibneft has chosen NNGP to conduct its well-logging services. "They have offered comparable quality of services at lower prices than Schlumberger," he added.

As an example of this new competitive environment, tenders between Inpetro, a Moscow research institute, and US-firm DeGoyler and MacNaughton Inc., for the pilot development plan of Sugmot show what possibilities lie ahead.

In this case, "Degoyler and Inpetro came up with comparable plans, a fact acknowledged by Degoyler themselves," Korsik said. "Yet Inpetro prevailed [because it offered a lower price]." Inpetro has also completed a number of projects for Western oil companies including one of the Sakhalin PSAs.

Recognizing its value, Sibneft purchased Inpetro and turned it into an in-house research and development business unit.

Social responsibilities

It turns out that finding a way to unhitch nonoil responsibilities would also require a similar strategy.

By the end of 2000, Sibneft had successfully spun off most of its social infrastructure and nonoil related activities by either turning these entities into self-sustaining businesses or handing them over to the municipality.

Clothing company Duar and publishing house Blagovest provide two Noyabrsk examples, created on the basis of assets that Sibneft used to have on it balance sheet. Sibneft says both companies have now become independent and economically successful. Blagovest, for example, now receives 40% of its business from outside Sibneft. And Duar manufactures coveralls for the oil field workers.

Sibneft has transferred 200,000 sq m of apartment, 100 km of road, sports facilities, and a hotel over to the Noyabrsk municipality. The company also paid $17 million to transfer these assets, but as a result, reduced its maintenance costs from $15 million/year to zero. Sibneft also sold off five collective farms employing 1,500 people.

In Omsk, Sibneft instituted a similar process where it transferred 537,000 sq m of apartment space, 12 kindergartens, and sports facilities to local authorities. Sibneft also sold non-core assets including a brick factory.

Russian business models

Sibneft attributes its successful restructuring to a screening process, unique for Russian companies. Beginning with baseline production, incremental investments are evaluated, along with all new investments.

Then 5 years of cash flows under several scenarios are examined. In turn, each project is evaluated on the basis of its internal rate of return, net present value, and payback. Once complete, the most profitable projects are finally selected.

Hurdles typically include a 22% discount rate while investments are tested at $16/bbl. Sibneft says that between the restructuring process and its investment screening process, it has cut costs by 30%.

"It's a good Volkswagen now, 2 years ago it was a Lada, and someday it may be a Mercedes," Korsik said in reference to Sibneft's operational efficiencies.

The final stage in the restructuring plan, to take place 2001-2002, will include turning many of the subsidiaries (drilling, workover, and construction) into independent companies. As a result, Sibneft will reduce headcount by another 10,000 to 17,000 employees.

When the company was privatized in 1995, it had 48,700 employees

The other way around

Another signal of Russian oil companies' focusing on new business models can be shown by a recent agreement between UK-based Sibir Energy PLC and Sibneft.

"This deal is absolutely unique for the Russian oil industry," Korsik said, "as Sibneft will supply the capital, technology, and management expertise, while our foreign-listed partner will contribute reserves."

Traditionally, Russian operators provide the resource base, whereas foreign companies offer financing, technology, and management know-how.

Ownership, management, and board representation will be split equally between the two partners. Located near Nefteyugansk in the Khanti Mansiyski Autonomous Okrug, both fields, which have PSA status, hold an estimated 2.1 billion bbl of recoverable reserves.

Under this JV, both companies will develop the south part of the Priobskoye field in addition to Palyanovksoye. Sibneft and Sibir have already begun development plans for both plays with pilot production from the Palyanovksoye field already running at 1,500 bo/d.

Sibir also holds a 50% interest through its Evikhon subsidiary in the Salym Petroleum Development venture with the Royal Dutch/Shell Group.

Energy trade system

Another innovative measure being taken by Sibneft includes its involvement in an internet-based trading system.

Taking its cue from Enron Corp.'s successful energy sales and trading business, Sibneft, the Russian Ministry of Railways, Transneft, Transnefteproduct, RedMeteor, and TransTeleCom Co. (fiberoptics) have begun work to develop an Energy Trade System (ETS) that will allow FSU petroleum products to be bought and sold electronically.

Synergies among these companies include a source of refined products, 86,000 km of railway transportation, 68,000 km of crude and refined products pipelines, and more than 25,000 km of fiberoptics. ETS will target the Baltic oil products market as its first test followed by the Black Sea.

According to ETS, 700,000-1.2 million bbl/day of refined product are exported to Europe, Baltic Sea ports, and Black Sea ports, involving any number of transportation vehicles, common delivery points, and common specifications.

If successful, the technology will become the first of its kind in Europe and will entirely replace the telephone, fax, and telex as key tools for physically trading petroleum.

Once the technology is in place, Sibneft says traders will be able to observe market parameters in real time while negotiating bids and offers under an environment of transparency and liquidity.

Seeking partners

Sibneft still has not given up hope in finding Western partners; several PSA opportunities have recently become available. Although Mukhametzyanov and Korsik feel they are "closing the gap with western companies," they are still seeking management know-how and cheaper access to capital.

"Right now, the problem of financing is not too acute, but no one knows what is going to happen in 1-2 years," Korsik said. "Anyway, when you have development projects like Sugmut, with almost a billion bbl of reserves, you need huge capital investments."

At a company celebration last September, President and CEO Eugene Shvidler provided another point of view. "If we enter a greenfield development in Russia, we would like to do so in partnership with another company, either Russian or foreign. This is not a question of our ability to muster the necessary financial or managerial resources, it is because we believe in spreading our risks."

Shvidler also explained that such risk-sharing partnerships are the norm, although in Russia unheard of. "Russian companies will have to learn how to work together, and that will require a change in mentality."

But as it once did with Elf Aquitaine, Sibneft no longer seeks an all-embracing strategic alliance with a single oil company. "Instead we are hoping to strike up a range of partnerships with various oil companies structured around individual projects," Shvidler said. "In the process, we will learn from our partners and avoid putting all our eggs in one basket."

Some of these opportunities include development of the Sugmut, Novogodnoye, and Yarainerskoye fields, which have been approved by the government's intergovernmental committee on PSAs (OGJ, Mar. 6, 2000, p. 27).

Additionally, the local legislature of the Yamalo-Nenetski Autonomous Okrug has approved the Romanovskoye oil field for development under PSA terms. As reserves at this field are lower than at the company's larger fields, the approval of the State Duma is not required. Oil industry consultant DeGolyer and MacNaughton has been commissioned to design a new development program.

Unfortunately, there is still very little information about the terms the government is offering in negotiations with oil companies. And obviously, export quotas remain a top issue for Western investors as Moscow remains unwilling to offer 100% export quotas for new PSAs.

Downstream

Upstream and midstream business operations form only a part of Sibneft's overall operation, as each subsidiary provides certain synergies for the entire corporation. As such, much attention has been paid to the refining and marketing sectors in order to improve efficiencies, provide new products, and expand the company's markets.

Sibneft exports about one third of its crude production, while the remainder is sent to the Omsk refinery, 1,000 km south of Noyabrsk near the Kazakhstan border. This facility has a total capacity of 385,000 b/d with a refining depth of 83.5% (sum of products less fuel oil, dry gas, and liquid fuels).

The company plans to invest $52 million in this plant this year, about five times more than in 2000 (Fig. 6, OGJ, Jan. 8, 2000, p. 49). This investment, which includes installation of new alkylation and catalytic reforming units, should increase throughput to 262,000 b/d from an expected 246,000 b/d in 2000.

As a result, Sibneft will soon begin first commercial production of A-98 in Russia. It will also allow increase production of A-92 (similar to US regular) and A-96. The facility produces no leaded gasoline and is one of the few in Russia to produce MTBE.

In recent years, Omsk's mix of refined products has changed as the share of gasoline increased at the expense of fuel oil. In 1999, gasoline output accounted for 28% of the total, while fuel oil output was 19%.

Markets

The Omsk refinery dominates product sales for the Omsk area and surrounding region. And compared to European Russia, particularly the Volga region where refining capacity is extremely concentrated, the Omsk refinery remains relatively isolated as transportation costs from outlying areas institute costly barriers of entry. The nearest competitors include Yukos's Achinsk refinery, 1,200 km to the east, and Lukoil's Perm refinery, 1,500 km to the west.

On the other hand, Sibneft can sell products to distant markets as it has access to two east-west products pipelines. Only half of Russia's 26 major refineries can plumb into this system because it was never developed to the same extent as the crude oil pipeline network.

Products pipelines obviously provide a much cheaper avenue of transportation than rail. The company's refined products are exported, sold on the wholesale market, or sold to the company's retail network.

In 1999, Sibneft sold about 85% of its refined product to wholesale customers, primarily in Western Siberia. In the past 4 years, the company has penetrated new markets including Krasnoyarks, Altai, Sverdslovsk, and Irkutsk.

Dealerships

To increase its downstream margins, the company has also created a regional network of dealerships (Fig. 7). In 1998, the following dealerships began operations: Sibneft-Ural (Sverdlovsk), Kuzbassnefteproduct (Kemerova), and Barnaulnefteproduct (Altai). Additionally, Sibneft established two new sales subsidiaries: Tomskneftesbyt and Polotsknefteproduct.

Primary sales regions for Sibneft are Omsk, Novosibirsk, Kemerovo, Altai, Sverdlovsk, and Tyumen. The company is also present in Krasnoyarsk, Kurgan, and Khakas regions, while it has been seeking to enter the Chelyabinsk, Tomsk, and Irkutsk regions.

In 2000, Sibneft purchased 199 outlets, up from 521 the prior year. Last December, it acquired two major Ural refined product retailers, Sverdlovsknefteproduct and Yekaterinburg, expanding its retail business into new markets.

These two companies control about half of the market in the Sverdlovsk region and control 132 gasoline stations and 20 storage sites. Combined sales for the first 9 months of 2000 totaled 480,000 tonnes vs. 390,000 tonnes in 1999.

Following this acquistion, Sibneft will control 44% of the region's gasoline markets against 34% for Lukoil, its closest competitor.

This year, the company plans to invest another $20 million, building 69 new gasoline stations and adding 70 more to its franchising network.

References

- Sergey Kolchin, "Lukoil loses top spot to Surgutneftegaz in Russia's oil shares," Oil & Capital, December 2000, p. 30.

- Gustafson, T., Capitalism Russian-Style, Cambridge, 1999, pp. 97-107.

- Freeland, C., Sale of the Century, Random House, 2000, pp. 187-88.

Horizontal drilling

An example of modern technology management can be shown in the recent implementation of a horizontal drilling program.

In January, Sibneft completed its first two horizontal wells, beginning an extensive program that is set to gather pace in the following months. Its first horizontal well in the Romanovskoye field, drilled in 40 days, began production at 1,550 bo/d, more than five times the company's average production from new wells.

"The horizontal drilling program will utilize a mixture of Russian and western techniques," said Dave Struthers, a Schlumberger drilling manager in Noyabrsk. "It's cheaper to use both systems than one over another, reducing cost perhaps by 50%."

The Romanovskoye well reached a total measured depth (MD) of 3,535 m with a horizontal displacement of 635 m (TVD= 2,870 m). Russian turbodrills, more efficient in the top hole section than rotary drills, were used until the kick-off point at 2,900 m (55° inclination).

Next, crewmembers tripped in with a bottomhole assembly (BHA) that included Western measurement and logging-while-drilling (MWD, LWD) tools and a positive displacement motor (PDM). This BHA then drilled a sharply inclined pilot hole for stratigraphic tie-in with the horizontal reservoir section.

Next, the pilot hole was cemented in and the parent borehole was kicked off above for tangential entry into the horizontal section. Again, a directional BHA was used but modified for purposes of geosteering, using the pilot logs as a stratigraphic go-by.

As production began on this well, Sibneft also completed a horizontal well at its new Yarainerskoye field. Additional horizontal operations include a well at Sugmutskoye and a second well at the Romanovskoye.

Struthers, who has been working in Russia for several years, has seen a slow acceptance of Western technologies. "The major changes in the way Russians drill their wells now include the use of MWD and LWD for directional and horizontal wells. Additionally, American drill bits, which last for hundreds of hours, and drilling fluids, which reduce formation damage, have had a large impact."

Traditionally, Siberian operators drill a cluster of wells from one well pad where the rig is moved from location to location on railroad-like tracks. Each well is deviated so that different parts of the reservoir can be accessed. In many cases, the well configuration is S-shaped with an initial vertical section, then a deviated section that is turned eventually back to vertical.

Pipelines for auction

A development on the horizon concerns new regulations governing export pipeline access.

Recently, the Russian government announced it will begin auctioning 25% of this capacity to the highest bidder. The remaining 75%, on the other hand, will continue to be divided among all producing companies based on a pro rata basis that is proportionate to production and distributed in the form of "extra allocations."

Depending on the results of the first auctions, the share of auctioned quotas may be increased. Smaller companies have voiced strong concerns because they do not have the political connections and access to capital needed to compete with the majors.1

Some majors, like Sibneft, support equal access to export pipelines for all producers and "is keen to end the current system," which is implemented through a nontransparent process. The company, however, sees the government proposal as a means to extract more revenues from the oil industry. "The introduction of such as system could have a serious negative impact on investment down the road."

For example, those companies that invest a high proportion of their cash flow in field development may have limited access to capital for the bidding process.

A new agency, the Khristenko Commission, has been set up to regulate the process. It is still uncertain how this ruling will affect joint venture and production sharing agreements in regards to export pipeline access rates and volumes.

Reference

- "The road to ruin?" Oil & Capital, December 2000, p. 6.

A strategic alliance

Sibneft's drive to improve productivity through the application of modern technology is exemplified by the company's strategic alliance with Schlumberger, intended to bring new technology and skills to focus on the long-term development of new reservoirs.

Relations between the companies date back to summer 1998 when Schlumberger, in competition with Russian companies, won a tender to provide hydraulic fracturing services for Sibneft production subsidiary Noyabrskneftegas.

The fracing initiative proved to be successful for both companies and within the first year added 3.6 million bbl to Sibneft's annual production. Some wells have seen an increase in daily flow rates from 43 b/d prior to treatment to 500 b/d afterward.

Incremental Steps

This cooperation led to the development of a broader alliance.

In order to deepen trust between the two companies, Sibneft deliberately developed the alliance in incremental steps. Initially, Schlumberger acted as service contractor on one of Sibneft's fields, with a gradual transition to a risk and reward arrangement.

In autumn 1999, a set of documents forming the alliance was signed. This enabled Sibneft to order new services without unnecessary bureaucratic delays. The range of services include:

- Drilling.

- Coiled tubing.

- Seismic studies.

- Nitrogen treatment.

- Reservoir stimulation.

- Downhole packing and tools.

- Directional drilling.

- Logging, testing and related data analysis.

- Reservoir modeling.

In late 2000, the alliance concept was developed further with the creation of joint groups uniting personnel from both Sibneft and Schlumberger. These groups have been working on the design of horizontal wells, the optimization of reservoir development, and pump optimization.

The next step

The next step, currently under active discussion, is the joint development of a new field.

Schlumberger may provide a series of services, such as drilling, logging, evaluation and pump optimization, working on a risk-reward basis. Holdith Reservoir Technology (HRT), a recent acquisition by Schlumberger, will develop reservoir models at the Yarainerskoye and Sporyshevskoye fields.

Sibneft has also worked with Schlumberger to optimise Noyabrskneftegas's own in-house services, with Schlumberger supervisors working with Sibneft specialists on workover procedures. As part of the know-how transfer, Sibneft now uses the reservoir simulation software, GeoQuest, for reservoir management purposes.

Overseas training

Sibneft says the most important part of the transfer of know-how is the training program for Sibneft production personnel. This training takes place in specialized Schlumberger training centers in Russia, the UK, and the US.

Part of the training for selected specialists is expected to include work on a field in Alaska under conditions similar to those in Western Siberia. Some 10-15 senior managers and about 300 mid-level specialists will be included in the training programs.

"We are hoping to strike up a range of partnerships with various oil companies structured around individual projects. In the process, we will learn from our partners and avoid putting all our eggs in one basket."