MMS to require casing pressure monitoring for subsea wellheads

The US Minerals Management Service has proposed that wells with subsea wellheads completed after Jan. 1, 2005, have the means for monitoring casing pressures.

MMS issued a notice of proposed rulemaking to amend its regulations for oil and gas well-completion operations. Under the proposal, published in the Nov. 9, 2001, Federal Register, operators would have until Jan. 8, 2002, to comment on the proposed rule.

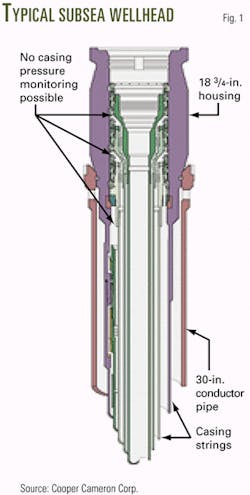

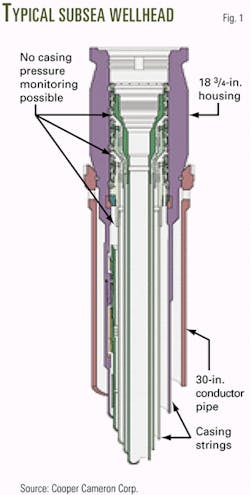

According to wellhead manufacturers, the requirement represents a technical challenge to existing subsea wellhead designs, in which casing annuli are isolated once subsequent casing strings are landed in the wellhead as the wells are drilled (Fig. 1).

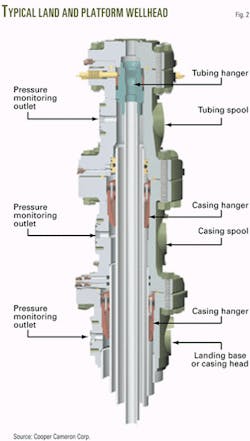

Wellhead designers and API standards intentionally minimize penetrations into subsea wellhead systems to reduce possible leak paths. This prevents operators from monitoring casing annuli pressures, unlike land and platform surface wellheads that can monitor pressure between casing stings through casing and tubing spool outlets (Fig. 2).

The MMS estimates operators' economic impact to be about 5% of the $3.5 million cost for an existing subsea wellhead, or an incremental cost of about $175,000/well.

Bobby Voss, project development manager for ABB Vetco Gray Inc., Houston, said this might be reasonable for the equipment costs. He said there could be other operational costs associated with the rule implementation.

Voss said the proposed rule revision is driven by concerns of annular fluid thermal expansion that could cause high pressure that, with existing subsea wellheads, cannot be monitored. This is a particular concern with high temperature, high-pressure wells or when large temperature fluctuations between producing and shut-in conditions result in thermal expansion of annular fluids.

Jim Regg, chief of technical assessment and operations support for MMS's Gulf of Mexico region said the MMS has been willing to grant departure requests for gulf wells with subsea trees. He said MMS has done so based on a higher level of design and the application of best cementing practices that go into deepwater wells (OGJ, July 2, 2001, p. 37).

Regg said the higher level of design is apparent from the permitting documentation and completion reviews for deepwater wells. The fact remains, however, that by not being able to measure pressures in the annuli, the industry is operating blind in this regard.

Regg said MMS encourages operators to think unconventionally to develop technologies and methods for safely completing and operating oil and gas wells in the deepwater gulf.

Contacted by OGJ, senior drilling personnel with several major operators in the Gulf of Mexico had little comment on the proposed rulemaking. One operating company employee said the narrow window between pore pressure and fracture gradient in the gulf, generally requiring a large number of casing strings, results in well completions that inherently should have fewer annuli pressure problems.

Other provisions of the proposed rule change will affect lease transfers. In the course of lease transfers, MMS proposes that the current lease operators be required to review all casing data and provide reports on the status of all wells with sustained casing pressure (SCP) to both the MMS and the new operator.

The proposed rulemaking also seeks to codify existing MMS procedures requiring operators to request a departure from MMS regulations to operate wells that have SCP, ensuring uniform regulatory practices among MMS regional offices.

Pressure monitoring

For several decades, the MMS has required operators to monitor and diagnostically evaluate any measured casing pressure in oil and gas wells. MMS defines casing pressures to be either sustained or unsustained.

Unsustained pressure can occur through gas lift or water-injection pressure, which operators impose on the well. Thermal expansion of existing casing annuli fluids can also create unsustained casing pressure, which can raise well-integrity concerns depending on the magnitude of temperature change as wells are produced and shut-in.

SCP occurs between a well's casing and tubing, or between strings of casing, if pressure rebuilds after being bled down. MMS says that data gathered indicate SCP is caused by leaks in production tubing, tubing connectors, seals, and other equipment. Poor casing cement bond and channeling in cemented annuli can also cause SCP.

Left uncontrolled, according to MMS, SCP represents a safety hazard. During 1980 to 1990, the oil and gas industry in the Gulf of Mexico suffered four serious accidents as a result of high SCP and the lack of proper control and monitoring of these pressures.

In response, MMS developed a policy for the gulf outer continental shelf, which has evolved into the current regulation 30 CFR 250.517, under which lessees must effectively monitor the SCP of wells in an attempt to avoid future accidents.

MMS has interpreted the regulation to mean that no SCP is to be maintained on any annulus of an OCS well for normal operation. Lessees may operate wells with SCP after obtaining MMS approval of a departure request. The lessee must perform diagnostic tests of the casing pressure and report all casing annuli pressures in order to submit the departure request.