Bossier play has room to grow, possible limits in East Texas

Petroleum exploration has often depended upon re-found opportunities in mature areas. No province reveals this better than the East Texas basin (ETB), which has undergone several rejuvenations of exploratory activity during the 1980-90s and is now at the turn of the century in the throes of yet another period of discovery and field expansion.

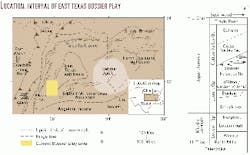

The current play is centered on gas-bearing, turbiditic sandstones of uppermost Jurassic age along the western flank of the ETB (Fig. 1). These sandstones include several units close to the boundary between the Bossier shale and overlying Cotton Valley sandstone, plus at least two units at greater depths, 400-500 ft below this boundary. Recent usage includes the first several units in the Bossier interval, though actual stratigraphic relations are complex. The second two units clearly fall within the Bossier proper.

Beginning in the 1970s, upper Bossier sands served as occasional secondary targets to deeper drilling for Haynesville and Smackover carbonates,1 particularly along the western flank of the basin. Prior to the mid-1990s, some 75 wells with roughly 50 bcf of reserves existed in the Bossier, mainly in Freestone County.

Since 1996, however, when the current play began, over 170 new wells with as much as 1 tcf of reserves, have been drilled and completed in Freestone, Leon, and Robertson counties. The most concentrated drilling is by Anadarko Petroleum Corp. in its Dew-Mimms Creek area, southern Freestone County. By October 2000, the company had drilled at least 160 wells in this area, was producing over 175 MMcfd of gas, and had 20 rigs active at new locations.

Current play areas

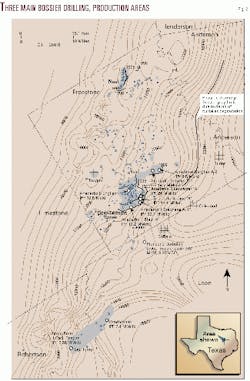

In broad terms, the current Bossier play can be divided into three separate areas of new drilling and completion (Fig. 2).

In addition to Dew-Mimms Creek, these include Neal field in northern Freestone County and one-well Reagan Ranch and Vanderbeek fields in the downdip area of northeastern Robertson and adjacent northern Leon counties.

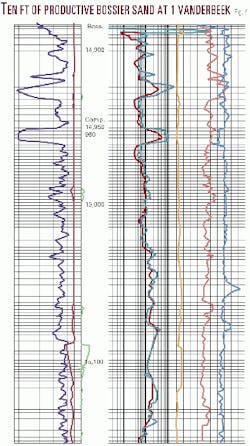

Neal field is the farthest updip area, discovered in 1990 and rapidly expanded after 1996 by Apache Corp. to include at least 16 producers. Reagan Ranch, a downdip field, was opened in 1996 by Broughton Operating Co. at its 1 Cecil Ranch well, originally a Cotton Valley lime (CVL) test that nearly blew out in the Bossier. Similarly, the Amoco 1 Vanderbeek, also a CVL test, received a strong gas kick in the Bossier but has only very recently (November 2000) been recompleted in this interval. The Vanderbeek well, in fact, represents a significant new addition to the play, since it has established high rates of production (7.4 MMcfd) from a 10-ft Bossier sand at the greatest depths yet recorded, 14,950-60 ft depth. Moreover, log data show that this same sand also exists in a number of surrounding deep tests, where it thickens up to 20 ft.

Bossier drilling is now being pursued by a dozen or more independents in total, encouraged by the recent spike in gas prices. Information suggests that the play is marginally economic at $2/Mcf, partly due to the need to frac most wells-but extremely profitable at twice or three times this price.

To some degree, Bossier drilling is a spinoff from the CVL "reef" play, an expensive, high-risk, and well publicized frontier trend intensively pursued during the mid-late 1990s and still active today. Cotton Valley lime activity generated vast amounts of 3D seismic data and related geologic analysis-knowledge that has added greatly to understanding of the ETB and that underwrites much of the current activity in the Bossier.

Geologic overview

Recent exploration for Upper Jurassic reservoirs in the ETB has confirmed the existence of a regional overpressure cell in the southern half of the province. Extent of the cell appears to correspond with maximum thickness in the Upper Jurassic section, which is reached in the southern portion of the basin and overlaps the downdip part of the western and possibly eastern flanks.

Within this cell, which extends from Smackover to uppermost Bossier and, in the basin center, lower Cotton Valley sandstone, porous units are gas charged and will produce on depletion drive, with little or no formation water. Reservoirs were originally charged with oil from Smackover and Bossier source rocks, cracking to gas having then taken place as a result of increased burial. Hydrocarbon charging appears to have retarded the later stages of cementation and, in the case of gas maturation, to have driven off a majority of formation water and aided development of overpressure. Top of the overpressure cell seems to largely correspond with thick, low-permeability deposits of the lower Cotton Valley sandstone.

Much of the current Bossier play, especially in Freestone County, seeks to exploit the overpressure cell by drilling for gas in moderate porosity sandstones close to the overpressure ceiling, i.e. at its shallowest levels. This translates to sand occurrence at depths of 12,400-13,200 ft. The more local , updip drilling in Neal field targets normally pressured sands at depths significantly shallower than this, at 10,400-11,200 ft. There are, however, as noted, deeper prospects in more downdip positions to Dew-Mimms Creek, and also along the Reagan Ranch-Vanderbeek trend to the south, in Leon and Roberston counties, at 14,000-15,000 ft.

Reservoir sands bear a certain resemblance to fine-grained, Late Tertiary turbidites of the northern Gulf of Mexico. They consist of gravity flow material deposited in prograding systems that filled paleo-lows between active salt highs, mainly in lower shelf and upper-to-mid slope locations. Bossier sands, in general, represent lowstand delta front and prodelta material. This material is the downdip equivalent to lowermost, updip Cotton Valley sandstone fluvial-deltaic complexes, which eventually prograded across the entire basin.

Sands occur within the upper 500-600 ft of the Bossier interval. At least five separate units have been identified in the Dew-Mimms Creek and Reagan-Vanderbeek areas, these being divisible on the basis of their stratigraphic position and location relative to the Bossier shelf. The upper three units (Taylor, Shelly, Moore) form major targets in Freestone County and have porosities of up to 15% and permeabilities of 0.1-1 md. A fourth unit, known as the Bonner sand, exists in more downdip portions of Dew-Mimms Creek, as well as in the Reagan Ranch area. The Bonner is deeper than the upper three units, exhibits higher levels of overpressure (e.g. 0.74 psi/ft versus 0.60 psi/ft in the Taylor-Shelly-Moore), and has significantly better reservoir quality, at 9-20% porosity and up to 10 md permeability. Finally, the Vanderbeek sand, currently productive below 14,900 ft, appears to have reservoir quality similar to that of the Bonner and even higher levels of overpressure. To date, this 10-ft sand is one of the only reservoirs to produce naturally at high rates.

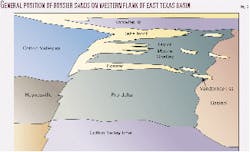

These sands, along with those of Neal field, can be seen to occupy different "steps" along the Bossier shelf (Fig. 3). The step-like architecture of the shelf is evident from 3D seismic data and seems related to a combination of:

- Rift-related basement faulting.

- Staged salt movement (increasing in the downdip direction) and associated faulting in the overlying section, and

- The development of carbonate buildups along the faulted edge of each "step," mainly in the Cotton Valley lime.

Sands occur as lenses, segregated pods, and channel trends that vary from a few hundred acres up to 10 sq miles in areal extent. Sand was transported to the shelf along both southwest and east-southeast oriented channels that spilled material to progressively deeper levels through various low points. Limited core information suggests that sands scoured into underlying muds and built to significant thicknesses through amalgamation. Transport was directly influenced by structural highs resulting from active salt features and by drape over carbonate buildups and shoals in the Cotton Valley lime. Re-entrants along the upper Bossier shelf helped focus sand catchment in certain areas, particularly at Dew-Mimms Creek.

Results from the farthest downdip wells in the play suggest an important change between north and south. In the north, downdip from the Dew-Mimms Creek area, there appears to occur a loss of reservoir quality below about 14,500 ft depth, beginning east of the Freestone-Leon county line. To the south, however, as evidenced by the Vanderbeek sand, no such loss of reservoir quality seems to occur (Fig. 4).

Play character

The Dew-Mimms Creek area is being developed on 80-160 acre spacing. Wells in the central and northwestern part of the area produce from the Taylor, Moore, and Shelly sands. Net pay varies from 75-100 ft.

Wells receive a light water frac and test at rates of 2-5 MMcfd. Declines are hyperbolic, with flows stabilizing after 2-3 years at 500-900 Mcfd. Wells appear to be capable of extended productive life (15-20 years), with estimated ultimate recoveries (EUR) of 1-4 bcf. In the more southeastern, downdip portion of the field, the Bonner sand has become a primary target. This sand exists on the next "step" down from the updip part of the field, at 13,200-500 ft. It tends to produce at significantly higher rates, with initial potentials ranging from 7-11 MMcfd to as much as 28-50 MMcfd in the best wells, with EURs of 3-10 bcf. This higher level of production is attributed to a combination of superior reservoir quality and increased overpressure.

The Bonner sand, or its rough equivalent, also produces in Reagan Ranch field of northeastern Robertson County at 13,650 ft. The Broughton Resources 1 Cecil Ranch, the only well in this field to date, nearly blew out in a 40-ft Bossier sand while drilling for a deeper Cotton Valley lime reefal target. Completed at a rate of 7.5 MMcfd, the sand received only very light treatment and has yielded 2.5 bcf to date, with a projected EUR of 4.5 bcf. If this is indeed the same, or equivalent, interval productive in the downdip Dew-Mimms Creek, it suggests a 40-50 mile trend for exploration.

The Vanderbeek sand, completed at a natural flow of 7.4 MMcfd at 14,950-60 ft (Fig. 4), represents another "step" down from the Bonner at Reagan Ranch. It has been identified on logs in a number of surrounding wells, including the Union Pacific 1 Lightning, 1 Bearcat, and 1 Thunderbolt.

Significantly, the sand exhibits similar log characteristics in these other wells and is of equal or greater thickness (up to 20 ft). This portion of the downdip play therefore should expand in the near future. If the sand is also present in other deep wells farther to the northeast (e.g. Sonat 1 Hodges, Amoco 1 Morris), a total play area of up to 35-40 sq miles could result.

Meanwhile, the operator has also completed the upper sand in the Vanderbeek well at a rate of 1.5 MMcfd.

Limits to current play

Possible limits to the current play, along the western margin of the ETB, depend upon both geological and economic factors.

Geologic factors include sand presence and quality, overpressure, and trapping. The overpressure cell has a northern limit roughly corresponding with the Freestone-Anderson County line and, along the western flank, with a subsea depth of minus 12,000 ft. The proportion of sand within the upper Bossier, meanwhile, decreases rapidly into southern Robertson County, south of Franklin.

Updip limits to productive drilling in western Limestone and Freestone counties, where overpressure is absent, will depend on the ability:

- To locate main channel trends where sands are thicker and of better quality (as at Neal field), or more generally

- To establish sustained economic production rates from inferior reservoirs through improved completion practices.

Basinward sand degradation appears to limit the downdip portion of the play in the Freestone-Leon County area. To the southwest, where such degradation does not occur, expense related to increased depth of drilling, very high overpressure, and added casing requirements, may together provide an economic limit. The presence of lower slope-basinal fan complexes at depths of 15,500-17,000 ft remains a distinct possibility, but are likely to prove expensive and challenging to drill.

At the same time, sustained high gas prices would almost certainly help expand the play north of the overpressure limit, for example into Anderson and Henderson counties, as well as to the east side of the basin. Logs from Cotton Valley Lime wells on the east flank suggest the existence of at least one Bonner-type sand, positioned 400-500 ft from the top of the Bossier.

Moreover, other Bossier sands, such as those in Glenwood field, Upshur County, could become targets of new activity. In addition, a 200-ft sand package known as the "Taylor sandstone," traditionally identified as the base of the Cotton Valley sandstone and bearing certain similarities to the Taylor-Moore-Shelley interval of the western flank, is an important reservoir in this area. This is especially so in Panola and Upshur counties, where as many as 1,500 wells produce and may also be rejuvenated by new drilling.

Other considerations

The Bossier sand play of East Texas represents one of the most exciting-and profitable-new exploratory ventures in the US energy industry.

In general, success of the play has encouraged operators to re-examine the whole of the western and eastern flanks of the basin. Like its immediate predecessor, the Cotton Valley lime "reef" play of the late 1990s, it also suggests new drilling opportunities along other portions of the Gulf Coast, e.g. in northern Louisiana, where certain similarities in general depositional setting existed.

Finally, a word about names used in the current play. There has been some debate about whether the uppermost "Bossier" sands currently being drilled in East Texas should really be considered lowermost "Cotton Valley sandstone" or not. The question is not without significance. Some workers have noted that applying the name "Bossier" to these intervals in effect frees them of certain older associations related to the "tight gas sands" of the Cotton Valley interval.

True as this may be, however, it is mitigated by the potential for an increased awareness of the regional potential of the play-which taken as a whole strongly suggests an important degree of continuity between the two intervals. It also suggests that any sand with adequate gas shows, particularly if it occurs within the overpressure cell, should be considered prospective at today's price levels.

Acknowledgment

This article represents material excerpted from the upcoming report, "Bossier sandstone play, East Texas basin," to be published shortly by IHS Energy Group as part of its Petroleum Frontiers series.

Reference

- Presley, M.W., and Reed, C.H. "Jurassic exploration trends of east Texas," in Presley, M.W., ed., "The Jurassic of East Texas," East Texas Geological Society, 1984, pp. 11-22.

The authors

Scott L. Montgomery is a Seattle petroleum consultant and author. He is lead author of the "E&P Notes" series in the AAPG Bulletin. He holds a BA degree in English from Knox College and an MS degree in geological sciences from Cornell University. E-mail: [email protected]

Robert W. Karlewicz is a consulting geoscientist living in Gold Hill, Ore. Before starting the consulting firm Capstone Energy Resources in 1999, he was a staff geoscientist with Jordan Oil & Gas Corp. in Healdsburg, Calif. He had worked with Jordan for more than 22 years. Karlewicz has been active in the East Texas salt basin Cotton Valley reef play since 1993. He received a BS degree in geology from Southern Oregon University. E-mail: [email protected]