Property acquisitions-2: How to bid successfully in a changed marketplace

The first part of this article discussed typical discount rates for winning bids in today's environment (OGJ, Oct. 29, 2001, p. 42). This demonstrated far lower economic returns of 10-12% net present value (NPV) for high quality properties than levels perceived 15-20 years ago.

In this concluding part of the article we attempt to define just how successful bidders arrive at their bids and why the marketplace has changed.

Arriving at high bids

To understand the answer to this question, a number of topics need to be examined. Among these are the following:

- Perceived cost of capital.

- The role of commodity price hedging.

- The role of lower confidence reserves.

- The impact of technological advances.

- Incremental savings when merged with existing operations.

- Valuing long life reserves and strategic considerations.

Each of these factors contributes to the final answer. If all or at least nearly all are not scrutinized and valued when formulating a bid, you can be sure that at least some competitors will consider them and outbid you.

Perceived cost of capital

In spite of a number of sources being available for the cost of capital, ironically it has been the authors' experience that those acquiring reserves pay little attention to such items as the weighted average cost of capital (WACC) or, for that matter, typical discounted rates of return common 15-20 years ago.

In summary lower commodity prices have made the upstream energy business more efficient in almost all areas, causing the industry to examine carefully what capital costs you as opposed to your competitor.

It is not the purpose of this article to delve into the fundamentals of WACC since the authors profess no expertise in this area. What is clear is that most of the classic estimates for WACC are post tax corporatewide calculations, and to arrive at a pretax number, the basis for most acquisition estimates, it is not just a simple matter of "grossing up" the cost of capital for the marginal federal and (if applicable) state tax rates for the following reasons:

- In most cases, the price paid for an asset acquisition becomes the basis for tax purposes. Just how that basis is applied is a case-by-case decision, but it will result in a tax bite less than the marginal rate.

- Recognized experts in the field (Ibbotson's web page3) recommend the use of effective tax rates as opposed to marginal tax rates to account for corporate losses, a well-known phenomenon in the upstream energy sector.

- A corporatewide calculation almost certainly will encompass uses of capital in more risky environments than the acquisition of a producing property. Those projects with higher risk (exploration, etc.) should bear their own cost of capital and not unreasonably impact the lower risk projects.

- Producing properties can be used to collateralize conventional bank debt, usually the lowest cost of capital these days, as opposed to a wildcat well for which the bank-borrowing base can be stated with precision at zero.

So where does that leave the bidder? If your effective tax rate is zero or 15%, you may be in a better position to cut the effective discount rate used in your acquisition analysis to your cost of capital and give yourself a competitive advantage. Of course, if you are to be a profitable company, this advantage will not always exist but it can certainly help you win that special property acquisition that pushes your company to the next level.

Commodity price hedging

Obviously one risk when valuing a producing property acquisition is what to use for commodity prices. This is especially true when prices are high (i.e., above historical norms if ever there is such a thing these days).

Price hedging, a subject unto itself, is one approach to limiting the downside (and sometimes the upside). Many acquirers have used this facility in the past and continue to do so today.

Currently in vogue are puts or floors which lock in minimum commodity prices in exchange for fees while at the same time placing no limits on the upside. The concept here is to purchase floors covering the first 3 or 4 years of an acquisition for most of the production, the length of time until payout, or at least within a year or so of payout.

This leads to structuring commodity price profiles in accordance with such floors that are at discount to the Nymex strip pricing in addition to whatever your company-pricing outlook might be.

Lower confidence reserves

The role of lower confidence reserves is the driving force behind the modern asset acquisition market. Without the ability to transform into proved reserves, there can be no justification for the high prices being paid.

Whether a transaction is apparently based upon a low return on proved reserves as described earlier or value is attributable directly to lower confidence reserves, there is little doubt that purchasers are paying for probable and sometimes possible reserves.

One reason for this is the ability to identify bypassed reserves and untapped horizons with new technologies such as 3D seismic. In other words, operators seek out and exploit these opportunities much more aggressively than 20 years ago with the knowledge that technologies such as 3D seismic can lower the failure rate significantly.

Said Gareth Roberts, CEO of Denbury Resources Inc.:5 "We do not buy just any fields that might be out there, but rather look for opportunities where we can increase the reserves. For example, a typical field that we acquire should provide us with the opportunity to double the acquired reserves through our own efforts."

Technological advances

New technologies, especially information technology, have played and will continue to play a leading role in opportunity identification and risk and cost reduction.

Marie N. Fagan, Cambridge Energy Research Associates, said:6 "The impact of technology, especially information technology, is widely credited as the main driver in reducing upstream costs and enabling the E&P industry to survive the 1986 oil price collapse and the oil price volatility that has followed."

Fagan concludes that better technology has driven down the crude oil finding and development costs in the US 55% onshore and no less than 80% offshore since 1981.

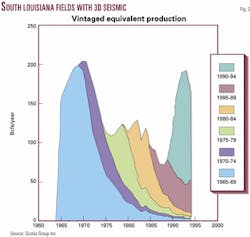

In a study completed by Scotia Group Inc. for Gas Research Institute covering 1995-97,7 it was determined that 3D seismic together with other technologies had transformed mature depleting fields to production rates in some cases near or in excess of the original peak rates of 20 or 30 years ago.

Fig. 2 is a vintaging plot based on 5-year increments since 1965 for fields in South Louisiana where 3D seismic was known to be the primary contributing factor to the dramatic rejuvenation of these fields.

From this same study are a few examples of 3D seismic success stories:

- East Cameron Block 331-332. Purchased for $100,000. After 3D seismic, 10 wells were drilled, discovering 174 bcf of reserves at a cost of $6 million and a net present value of $36 million.

- Yegua play, South Texas. Before 3D seismic and AVO analysis, the success rate was 15%. Success rates are now over 50% with 300 bcf of gas reserve additions in Wharton County alone.

- South Louisiana. An operator purchased five mature fields from major oil companies. Following 3D work, the operator increased production fivefold to 6,000 boe/d in two of the fields. The value of the properties was increased to $138 million from the original purchase price of $44 million.

- Viosca Knoll, offshore. As a direct result of a 3D seismic study, off-structure sand thickening was postulated. This resulted in Consolidated Natural Gas Co. booking 190 bcf of reserve additions, the largest single addition in that company's history at the time.

With this type of performance improvement it is not so surprising that the Energy Information Administration8 and the US Geological Survey9 10 both concluded that there are more US reserve additions within known field boundaries than contributed as a result of new discoveries. EIA's proved reserves data for the US indicate that during 1977 through 1995, 89% of additions to proved oil reserves and 74% of proved gas reserves occurred in known fields.

Incremental savings

Potential synergy with existing operations is one of the driving forces in the megamergers that have occurred in this industry in recent years. Such mergers usually result in large layoffs as many corporate functions do not need to be duplicated.

Asset acquisitions as discussed here do not usually involve the integration of people and as such are likely to offer less opportunity for synergy. However, if the properties being acquired are in the same geographic area as the purchaser's existing properties, there clearly is opportunity for lowering operating costs.

Usually independent reserves reports, the most common starting point for purchase price bid analysis, will employ operating costs based on the seller's last 12 months of operations. If the seller has lost interest in the property or is selling to rationalize a portfolio, the operations themselves may not be optimized from a cost or performance basis. Of all the factors influencing acquisition price, this is unlikely to be the most significant but it nevertheless deserves consideration.

Strategic considerations

Another aspect that impacts the apparent value of properties concerns the estimated life of the property in question.

Taken to its extreme, a property that enjoys high rate wells but a steep decline such that most of its reserves are produced within 5 years of purchase will be relatively insensitive to the discount rate used. In comparison, the value of a long life property where peak production may be years away can literally be decimated by the use of discount rates of around 20%.

In these circumstances the acquirer has little choice but to acknowledge that such extremes cannot be valued using the same rules.

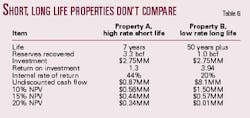

Table 6 illustrates this phenomenon for two hypothetical properties having the 15% NPVs in the same range. Which would you rather own?

Clearly the two projects cannot be compared simply via a target rate of return. By any standards the high rate short life project A is at best marginal. Project B, the low rate long life alternative, displays good economics if your target rate of return is 10-12%.

David and Hickman11 conclude the following with respect to valuation of long-life reserves (LLR):

- "As attested by the apparent high prices currently being paid, reserve acquisition is a business decision guided by engineered projections and not solely an engineering exercise.

- The applicability of classic comparative project economics plays a diminishing role in today's competitive reserve market.

- The conventional adjusted DCF/ROR evaluation methods that guide management in their decision undervalue LLR.

- The intrinsic nature of LLR-low decline, risk deferral and dispersion, and reduced reinvestment requirements-can contribute significantly to a company's strategic position.

- The concept of advantage ownership applies. Depending upon the structure, source of capital, degree of commitment, etc., LLR are of more value to some companies than others.

- Using conventional methods, many companies are unable to make competitive offers for LLR."

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Tim Perry, senior vice-president, Credit Suisse First Boston, for sharing his recent experience on asset acquisition criteria for winning bids.

References

- Perry, Tim, Credit Suisse First Boston, personal communication, 2001.

- Escher, Al, "E&P Strategy Prepares Producers for 21st Century," OGJ, Sept. 25, 2000, p. 30.

- Ibbotson and Associates web page.

- Eads, Ralph, "Winning Bidder Valuation Criteria," Houston Producers Forum, June 15, 1999.

- Roberts, Gareth, Wall Street Transcript interview, Apr. 30, 2001.

- Fagan, Marie N., "The Technology Revolution and Upstream Costs," The Leading Edge, Society of Exploration Geophysicists, June 2000.

- Scotia Group Inc., "Future Gas Resource Evaluation & Technology Impacts In The Gulf Coast Area," GRI Contract 3094-210-3429, published by GTI, December 1997.

- Morehouse, David F., "The Intricate Puzzle of Oil and Gas 'Reserves Growth,'" Energy Information Administration, Natural Gas Monthly, July 1997.

- Schmoker, James W., "Reserve Growth Effects on Estimates of Oil and Natural Gas Resources," USGS Fact Sheet FS-119-00, October 2000.

- Schmoker, James W., and Dyman, Thaddeus S., "Changing Perceptions of World Oil and Gas Resources as Shown by Recent USGS Petroleum Assessments," USGS Fact Sheet FS-0145-97, August 1998.

- David, A., and Hickman, T. Scott, "What is the Market Value of Long-Life Reserves?," SPE 20508, 1990.

The authors

David I. Heather cofounded Scotia Group Inc. in 1981. Before that he was with Texaco Trinidad and Humphrey & Glasgow Ltd. He has developed economic and strategic planning models for the domestic and foreign oil and gas community. Current efforts are directed toward development of management tools to assist in the exploration and acquisition decisionmaking process. He earned a BS degree in chemical engineering at the University of London. [email protected]

Gene B. Wiggins III is senior vice-president of engineering at Scotia Group Inc. and co-manages the company's Houston office. He has more than 23 years' experience as a consultant and in business development capacities for various companies. He has an MBA degree from Tulane University and a BS degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Houston. [email protected]