UNDERGROUND GAS STORAGE - Conclusion: Industry-segment uses reflect evolution of storage

Changes in the US natural gas industry in the past 2 decades have been revolutionary: commoditization of natural gas, growth of market centers, pervasiveness of risk-management tools, and electronic trading. These changes have profoundly affected the use of underground natural gas storage.

The first of two articles on the evolution of natural gas storage use in the US (OGJ, Oct. 8, 2001, p. 48) reviewed how forces have changed the industry; this concluding article reviews the past and current uses of storage by customer segment.

Both parts of this series are based on a longer report prepared by International Gas Consulting Inc., Houston, for the American Gas Association, Washington.

The value of storage is linked to the market demands served by storage users: pipelines, LDCs, marketers, independent storage developers, and electric generators.

As with all segments of the gas industry, storage is evolving to a client-driven business, in which the seller of the service must know and anticipate the needs of the market, sometimes even before that market does.

Numerous alternatives are available to consumers in their effort to minimize costs while managing their supply portfolios. The value of storage has to compete with these alternatives, both in price and quality of service.

Uses of underground storage

A key concept regarding the value of storage is to realize that throughout the regulatory evolution of natural gas storage use, local distribution companies, pipelines, and gas producers mutually benefited from the security of ongoing, amiable business relationships among companies.

In general, the same end-users have benefited from service from the same facilities (pipelines and storage) and received their gas supply from the same group of producers. Many markets were served by only one pipeline and used only the storage facility or facilities that were closest to their city gates.

Even today, many storage facilities still contract a large percentage of their capacity to these same end-users to meet peak demands of their markets, regardless of all the regulatory changes.

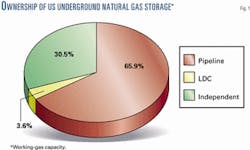

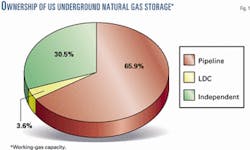

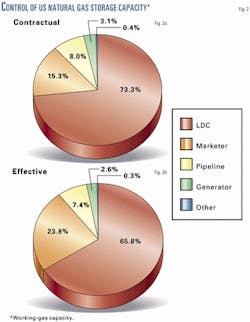

Figs. 1 and 2 show three different views of the control of natural gas storage assets today.

Fig. 1 shows the ownership of storage by company type.

Fig. 2a uses data from the index of customers reported to the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, augmented with proprietary data on the portion of storage not subject to FERC jurisdiction, to show the portion of storage capacity controlled by each company type.

By "contractual control," we mean the primary holder of capacity under terms of a contract with the owner in which it has maintained the storage for its own use. Contractual control may or may not be effective control.

Where use of the storage had been given to others, by means of an agency agreement of one form or another, then effective control of that storage is deemed to be with the agent.

Similar data were used to create Fig. 2b, which takes reported agency agreements into account to identify that portion of storage effective control held by each type of user.

A great deal of the recently developed storage capacity has been developed and marketed by independent storage developers. The term "independent developer" does not mean, however, that these companies are completely free of regulation.

As a practical matter, almost all storage facilities are subject to either state or federal regulation. Some independent developers may be affiliated with a regulated utility company, but a regulated pipeline company or LDC does not own the storage itself. Despite the increasing role of independent storage developers in the industry, Fig. 1 clearly shows that more than 96% of all underground US gas storage capacity is still owned and operated by pipeline and natural gas utility companies.

Fig. 2a illustrates a different point. Although pipelines own nearly 66% of the storage capacity, they have contractual rights to only about 8% of the working-gas capacity; most of the pipeline capacity is contractually committed to LDCs. Marketers and electric generators also hold a significant share of storage capacity under contract.

As can be seen in Fig. 2a, LDCs and, to a lesser extent, pipelines and electric generators have transferred a significant share of the effective control of capacity to marketers. Marketers have increased the share of storage they have available for use from 15% to nearly 24% of all of the working-gas capacity.

It is necessary to understand storage use by industry segment to appreciate fully the value of storage in the marketplace and to understand how these assets are being used.

Pipelines

Pipelines own 66% of the total working-gas storage capacity, but most of this capacity is under contract to others. About 8% of the storage capacity owned and operated by pipeline companies is actually used by the pipelines for operational balancing.

The remainder is contracted to others, primarily to the LDCs that were granted access to storage and transportation when the pipelines were required to abandon their city-gate delivered merchant services under FERC Order 636.

That order allowed pipelines to retain only such storage as required for operational integrity and "no-notice" service support.

Open access and the elimination of merchant gas sales services have caused the pipelines' storage operations to become largely "warehouse" operations. But pipelines are finding additional ways to use the storage capacity under their control.

"Parking and lending" services and intraday and hourly nomination services (as required by electric generators) are some of the new flexible-rate pipeline services that explicitly or implicitly utilize storage capacity.

Parking and lending services provide additional flexibility in customers' receipts and deliveries. Parking is typically a 24-hr "storage" service; lending is usually provided from operational working gas (line pack) on a best-efforts, as-available basis.

Recent FERC filings by pipelines reflect the new market demands of varying levels of hourly flow during the day. Certain pipelines have instituted hourly rate schedules or provide parking and lending services to enable end-users additional flexibility in gas takes.

To provide these services, pipelines increasingly rely on storage to meet these fluctuating loads. The availability of these services can reduce the need that users have to contract for storage service directly.

Local distribution companies

LDCs own and operate about 31% of the total working-gas capacity in the US. Further, LDCs are the primary contract holders of pipeline storage capacity, giving them ownership or contractual rights to about 73% of the total storage capacity.

LDCs continue to see value in directly owning storage assets and maintaining control over what is potentially a critical contributor to their supply portfolio. But many have also seen value in the tools available to marketers to utilize the storage they control more intensely. As a result, several of them have chosen to turn over effective control of their storage capacity to those marketers.

LDCs utilize storage, primarily storage in the market area, for seasonal baseload, for daily operational balancing, and emergency back-up service. The key objective for LDCs is to fulfill their "obligation to serve" at the best possible cost; storage accomplishes this obligation by providing supply security and peak-day coverage and a price arbitrage tool.

This concept of "obligation to serve" simply means that, in exchange for being allowed to be a monopoly, the utility must not fail to deliver natural gas to its core residential and such critical-needs customers as hospitals and schools. The utility must provide this service on a non-discriminatory basis to all customers who desire it within the franchise area.

In addition, the LDC uses storage to minimize pipeline capacity requirements, provide balancing, and avoid imbalance penalties. Ownership of the storage gas, proximity to the point of consumption, and minimization of pipeline demand charges all contribute in the LDC storage use decision process.

When contracting for new assets to develop their gas portfolios, the planners for LDCs must determine just how much seasonal variation to expect and then how much seasonal service, storage or swing gas, must be contracted for.

Similarly, they must determine how much needle peak-shaving (system storage or liquefied natural gas or both) in a design winter will be required. The remaining demand consists of some combination of city-gate delivered gas supply contracts, pipeline supplies, and storage that minimizes the pipeline demand charges while maximizing the load factor on each segment of the supply portfolio.

Load factor is the ratio of the amount of gas a customer actually takes compared with the maximum amount the customer is contractually entitled to take. This can be expressed daily, weekly, monthly, or annually.

Additionally, some LDCs are positioning themselves to be a "total energy provider" by forming subsidiary companies that offer a new range of energy services, beyond the traditional gas distribution service.

As noted, however, LDCs must ensure supply adequacy and manage system operations at the lowest possible cost. And, utilities rely on storage to mitigate winter price spikes and to implement hedging strategies with respect to the price of gas injected and the price of gas sold.

Gas marketers

Gas marketers include wholesale marketers and non-utility retail marketing companies including unregulated marketing companies affiliated with pipelines, LDCs, and producers. These players are the primary drivers of the transition in storage utilization.

The regulatory changes that led to the commoditization of natural gas created the environment in which gas-marketing companies were born. These companies were the first to apply risk-management tools, location and time-based arbitrage, and the commercialization of transportation and storage assets to the natural gas industry.

(Arbitrage refers to the trading of the same commodity on multiple markets in order to capture the value of any pricing differences that occur between those markets.

Buying gas at one location and selling it at another is a form of arbitrage. Buying gas today and placing it in storage while immediately selling futures contracts to capture the difference between today's cash value and the futures value is also arbitrage.

Because markets and futures move somewhat independently over time, it is common initially to lock in a profit when taking a storage position that is enhanced over time by capture of additional arbitrage opportunities. Typically, arbitrage is a low or no risk transaction.)

Natural gas storage is so valued by these users that they have increased their effective control of storage assets from nearly nothing just a few years ago to nearly 25% of all capacity available today.

A marketer may approach the evaluation of underground natural gas storage as the acquisition of a strategic asset that will enhance the company's gas-management function. This approach to the storage market offers the opportunity to differentiate the company as a value-added gas marketer.

In addition, the gas supplier's recognition of the need to be a low-cost provider in an increasingly competitive business requires the flexibility and reliability provided by storage. Storage is viewed as an asset that will help meet those objectives.

The marketers do business on multiple pipelines and have a real need to balance their sales volumes on many, often on more than 15 to 20 interstate and intrastate pipelines. It is simply impractical for these companies to rely on direct physical interconnects to balance their supplies and sales across all of these systems. The gas-supply operations of the marketing companies require well-located and interconnected storage-service options to support the required balancing and wheeling.

The evolution of the pipeline rules regarding balancing has contributed to the entry of larger gas-marketing entities into the storage market as developers, clients, and agents. They profit by bundling the storage cost and service in complete gas-supply packages that cater to the end-users' needs.

Typically, the marketer will offer the gas-supply services in multiple markets, spreading the cost of the storage over all sales volumes creating efficiencies unavailable to a single end-user operating in a solitary weather pattern. The marketers recognize that on rare occasions they may be forced to deliver simultaneously on all their swing sales contracts, but far more often, they will not. Here they can use storage in conjunction with the liquidity in the market to balance their risk.

Marketing margins have been squeezed by aggressive, competing pricing strategies focused on high volumes. The collapse of the premiums for gas-supply services has resulted from a furious competition among marketers attempting to gain market share through the customer-specific use of service quality, guarantee quality, storage volume, equity gas supply, dedicated pipeline and contract gas, and supply security.

Gas marketers competing in this environment apply assets to the gas supply, maximize leverage on flowing gas, and re-bundle as much premium service with their gas-supply sales as possible.

Examples of value-added services being offered by marketers using storage capacity include the following:

- Swing service is a gas supply offered as the last gas purchased and first curtailed by the customer if there is sufficient change in demand. Swing gas can be used to follow both seasonal and daily variable load requirements within contractual limits of a specific agreement.

- Balancing service equalizes gas volumes when daily withdrawals from and injections into the pipeline system are not balanced. This service avoids the imbalance penalties levied by the pipelines, which can be especially punitive if the pipeline is experiencing difficult conditions that have caused it to issue an operational flow order.

- Contract warranty service is a gas sales contract in which the seller commits to deliver a stated quantity of gas over a specified time, without limitation or commitment of specific resources.

- Emergency supply service is available to meet emergency conditions such as loss of alternative supply as may occur during such extreme weather conditions as a hurricane, well freeze-offs, extreme cold, or failures by other suppliers.

Value-added services enhance the value of the basic gas commodity and carry a price premium in the marketplace. These services typically require relatively small storage volume capacity in proportion to the size of the commitments.

In addition, LDCs and gas end-users are looking to suppliers to provide price hedging tools, such as price caps (limits on the maximum price regardless of market conditions) or cap and collar arrangements (limits on the maximum price coupled with a minimum price). Futures and option market tools coupled with gas storage are often used to reduce the risk of offering these products.

In addition, marketers and supplier-aggregators are able to gain value from arbitrage, daily trading, hedging and futures activity, and balancing services. Arbitrage refers to the capture of pricing differentials that exist over both short time spans of days or weeks and longer spans of several months.

Some storage facilities have tariffs that allow users to capture seasonal gas price differentials. A trader can acquire production at a set price and sell futures at a price that covers the storage fees to park the gas until that future time. This provides a margin of profit on the single transaction. By engaging in an active futures-trading program, traders may more fully exploit potential arbitrage profits.

The increasing industry use of the NYMEX futures exchange reduces the risk of capturing such differentials. In December 1998, for example, there were opportunities to acquire Gulf Coast natural gas production on the daily market at prices of less than $1/MMbtu, while January 1998 futures were selling at about $1.95/MMbtu.

With the marginal cost of salt cavern storage utilization at $0.07 to $0.15, anyone with access to flexible storage capacity had the opportunity to make significant profits. Larger volumes of storage, supported by interruptible injection and withdrawal, are generally suitable for this service. The active, liquid market that exists in conjunction with dramatic weather-driven changes in the supply-demand balance frequently creates such opportunities to profit from storage.

Even if the current "strip" of the New York Mercantile Exchange does not reflect enough seasonal pricing variation to support the full cost of storage, active traders can often time their cash market and hedging transactions to take advantage of seasonal spreads as they occur. (The NYMEX strip is the average of the 12 months' future gas prices. There are also summer strips and winter strip that average these respective timeframes.)

Hedging and futures trading facilitate the ability to arbitrage gas price over time.

Storage clients can also use storage to take advantage of gas and transportation price variations that take place daily.

Working with forward market contracts affords the opportunity to exchange gas among various physical locations and pipeline systems.

The net effect is that traders can sell gas during peak demand periods from market-area storage and replenish that gas storage supply during times of inexpensive release capacity on the long-haul pipelines interconnecting the field and market-area storage.

The strategies that marketers (however identified) use to profit from the use of storage are complex and interwoven. Hedging and arbitrage programs are combined with swing sales commit ments and balancing needs.

The effective implementation of these programs requires considerable skill. Marketers who do this make substantial investments in information systems and personnel in addition to the capital necessary to support these transactions. They also accept certain risks for the use of storage and, in some cases, commodity price risk as well. Although marketers in many ways have the best opportunity to profit from the commercialization of natural gas storage, that opportunity is neither cost nor risk free.

Independent developers

The newest participants in the distribution of storage ownership are the independent storage developers. These are typically small firms able to secure institutional or private financing to pursue storage projects. They are not associated with LDCs, pipeline companies, or oil and gas firms, thus the designation "independent."

Participants in the development of storage have shifted over time, primarily in response to changes in regulations and market demand.

Originally, development was limited to the LDCs and then the pipelines, both of which bundled in the cost of storage with the cost of gas supplies and transportation and passed the packaged service and fees onto their customers. Then electric utilities and a few private companies began to develop storage to satisfy their internal needs for gas supplies, that is, to become increasingly self-reliant.

As unbundling and deregulation disconnected storage services from the other components of gas supply, entrepreneurs became interested in the potential profit opportunities offered by storage. Now, the gas storage industry is experiencing interest in storage development by the large trading companies.

Independent developers are among the most aggressive users of natural gas storage facilities. Through their gas marketing and trading affiliates, they are utilizing the multi-cycle and quick response capabilities of high deliverability storage to execute gas pricing arbitrage strategies and hub-to-hub trading activities.

Just as with marketers, developers have the ability to take advantage of location and transportation price variations, to utilize gas-pricing arbitrage strategies together with least-cost gas supply practices, and to develop an asset from which to sell value-added gas supply services. A developer-operator can optimize the facility's capabilities by utilizing capacity contracted to others, on an interruptible basis, when the contracting parties are not using it themselves.

Electric generators

New developments in gas storage have emerged recently with the deregulation and growth of the electric industry. FERC Orders 888 and 889 initiated new competition among electricity providers by requiring open access on electricity-transmission systems and requiring separate prices for generation and transmission.

This deregulation effort allows electricity users to choose the lowest-cost electricity provider, which in turn prompts new competition among the generators of electricity. This deregulation shift is further extended with the unbundling legislation passed or being developed in most states. Although the impact on LDCs is still unfolding, deregulation is affording more opportunities for LDCs, marketers, and producers to sell re-bundled gas-supply services, including storage, to electric utilities and independent power producers.

A competitive market will reward those generators that can access the most competitively priced fuel delivered to plants reliably and on time. Natural gas is the fuel of choice to meet this impending increase in demand.

Low capital cost, short construction time (due primarily to siting issues), and lower emissions are the primary factors that will lead this shift to natural gas. In addition, gas-fired generating units have high efficiency, flexibility in operation, small module size, and are readily available, making them an attractive choice.

The US Department of Energy has forecast that demand for natural gas in the US will increase from 3.7 tcf to 7 tcf by 2010 and 11.5 tcf by 2020.

This opens an enormous opportunity for natural gas storage because storage can be the most secure, economical way to deliver natural gas at variable hourly rates as required by power plants. Natural gas storage can fill this emerging requirement in a variety of ways, including:

- Storage provides load-following gas supply for peak intervals of power generation.

- Storage also provides the opportunity to lower fuel costs below market if storage injections are made during periods of lower gas prices. Using high-deliverability storage facilities and cycling gas out of storage multiple times throughout the year can spread the fixed costs of storage over a larger volume of gas, thereby lowering unit costs of storage.

This assumes the availability of pipeline capacity to and from storage. As this infrastructure is used more intensively, the opportunity to cycle storage may be constrained.

- Storage facilities that are close to generating units provide secure gas supply, no transportation costs, and the ability to engage generating units immediately during periods of peak electric prices. These factors combine to make on site storage a financially attractive venture.

Alternatively, storage and electric generating facilities should be connected by pipelines that provide secure and flexible services, thereby avoiding the uncertainty related to capacity constraints.

- Small, high-deliverability storage facilities along a gas pipeline system allow the pipeline to manage line pack better and provide hourly transportation services for electric generation customers.

- Storage can provide physical product support to power trading activity.

Storage data

There are no definitive data available to identify the portion of storage currently being used to serve utility functions vs. that which has been made available for commercialization.

It is possible, however, to determine how much natural gas storage capacity is available and who owns and operates it. It is possible to identify those firms with storage under contract and how much capacity each party controls. Data are available to show how much capacity is being used, but no data in the public domain identify firms using storage capacity or how it is being used.

It is clear to industry participants that the trend toward the commercialization of storage is growing, but the lack of reporting data, the absence of standard definitions of use, and the fact that the complexity and subtlety of Agency Agreements (defined in Part 1) make it possible for a given unit of storage capacity to be used for both utility and commercial purposes make it impossible to quantify the degree to which the conversion has taken place.

The commercialization of natural gas storage increases the value of information regarding storage utilization and decreases each participant's willingness to provide that information. Since storage is a key component in the dynamic balancing of natural gas supply and demand, accurate and timely information about storage inventory levels and injection and withdrawal rates promotes the transparency that supports an efficient market.

On the other hand, to commercial participants, the information about their storage position is proprietary. As cynical as it may seem, the ideal situation for a trader is to have perfect information about everyone else's position while keeping his own secret.

Currently there are only two publicly available information sources reporting US natural gas storage activity.

The first is the US Department of Energy's Energy Information Administration, which publishes monthly information on storage injections, withdrawals, inventory levels, working gas, and base gas. This information is available state-by-state. The source is a mandatory monthly underground gas storage report (Form EIA-191) that is submitted by all storage operators. Publication occurs several months after the activity reported.

The second source of information is the weekly American Gas Storage Survey published by the American Gas Association. The data are gathered by voluntary reports from gas storage operators across the country.

The survey reports the weekly changes in the storage inventory for each of three regions defined in Part 1. The large regions help protect the anonymity of the participants.

Participation rates vary significantly from region to region. In the Consuming Region-East, operators of 92% of the storage capacity participate. In the Producing Region, operators of 78% of the storage capacity participate. In the Consuming Region-West, operators of 76% of the storage capacity participate.

The data are adjusted to estimate the total storage inventory in each region based on the survey data. The large regions tend to mask meaningful distinctions in the way it is used within each region.

The AGA survey is timely information widely relied on by the natural gas industry in assessing the supply and demand balance.

The continued commercialization of natural gas storage may increase the pressures on participants to withdraw from the AGA's voluntary sample.

The pressure may be offset, however, by the value the industry places on the availability of timely accurate information.

The fact that the AGA survey covers storage operators, as opposed to storage users, helps account for the high participation rates. Operators aggregate the information at the system or facility level, which the AGA further aggregates at the regional level.

As indicated, as the use of storage changes, the interpretation of storage data needs to change as well. Storage inventory statistics are aggregate numbers reflecting the use of storage by many companies, each independently determining what it should do to control risk, meet its obligations, and maximize value.

The availability of new tools in the industry to meet supply obligations may increase the efficiency of storage, resulting in lower inventory requirements. On the other hand, the availa bility of new opportunities to profit from the use of storage may result in greater utilization rates in periods when price volatility is greatest.