Economics strongly motivate operating companies to set up drilling management systems that have active feedback from post-well analysis to real-time drilling operations. This particularly is true when drilling budgets are large, relative to a company's overall spending.

More than 100 years ago, Anthony Lucas, an Austrian engineer who immigrated to the US, made a major oil discovery at Spindletop near Beaumont, Tex. The commonly held belief was that oil didn't exist in the shaley sediments near a salt dome. "Captain" Lucas doggedly pursued a vision that oil was there and, from an exploration point of view, ushered in a new era of finding it.

Captain Lucas and the Hamil brothers could never have known the enormous industry their first rotary drilling had kindled. Jim and Al Hamil, who owned and operated drilling rigs in that day, applied rotary drilling to water wells. Until the Spindletop discovery, the industry used cable tools to drill oil wells. While drilling the Spindletop well, Lucas and the Hamil brothers innovated many rotary-drilling concepts still used today.

Fast forward to the future, Captain Lucas's rotary drilling system, designed for less than 1,000 ft TD, has evolved into offshore drilling systems capable of drilling wells in water depths to 10,000 ft and to over 20,000 ft TD. Lucas and the Hamil brothers could never have envisioned wells that would reach over 33,000 ft laterally, wells with horizontal sections over 5,000 ft, or vertical wells routinely drilled past 25,000 ft.

With notable exceptions in the Middle East, drilling consumes 30-60% of most companies' E&P spending and drilling costs dictate everything from the scope of exploration programs to determining the economic viability of projects.

New exploration and exploitation projects follow technical innovations in drilling. For the past 40 years, drilling innovations have enabled a few thousand drilling rigs to provide much of the energy for worldwide economic development. But what about the future?

Drilling trends

The E&P industry has changed dramatically within the last 5 years, with:

- The creation of megamajors.

- Continual emergence and buying of new companies.

- A diminishing population of E&P workers and professionals.

- An aging work force having a median age of 42-46.

- Reduced research and development spending, especially for drilling.

- A reduced number of drilling contractors and service companies.

- An explosion in computing capacity and a continual growth of internet and communications bandwidth.

An increasing population of consultants, especially at the rig supervision level, have emerged from the mergers, buyouts, and downsizing. The industry is becoming ever more dependent on a cadre of contract personnel such as rig supervisors, drilling engineers, pore pressure analysts, and mud engineers.

Every segment of the drilling business is replete with consultants, most of whom are highly experienced and more than 50 years of age.

Another fallout is drilling contractor's steady growth in techno-ability. No longer satisfied with just providing "dumb iron," many drilling contractors have upgraded driller controls and automation, installed information technology and communications capabilities, and increased levels of training. Some have included engineering support for all aspects of drilling operations.

Managing portfolios

The nature of a company's drilling portfolio, its ability to "performance-manage" the portfolio, its understanding of how to adapt to new trends all affect the impact that drilling costs and drilling competency will have.

Organizations that classically manage drilling operations are likely to fall victim to increasing drilling costs leading to fewer wells drilled or large project overruns in both time and cost. The severe outcomes could affect everything from reduced exploration to higher hurdle rates for projects heavily dependent on drilling performance.

For many companies, the effective management of their drilling portfolio could be the critical factor determining near and long-term company performance.

One could compare the drilling portfolio with a stock portfolio. At one end are the more shallow, vertical, low-risk wells.

On the other end are high-risk, complex wells that range from deepwater wells of 20,000 ft TD or more and extended-reach wells with 30,000 ft MD of lateral extension to deep, high-pressure, high-temperature wells. Between these extremes lie wells having a variety of risk and complexity.

Megamajors and the larger majors generally build their portfolios around higher-risk, more complex wells, which reflect the trend toward deepwater exploration and prospects in more-challenging environments.

At the other extreme are companies that avoid high-risk projects and drilling, concentrating all their monies on lower-risk wells. Still others have mixed portfolios of low, medium, and high-risk wells.

Managers are challenged to get the most out of their portfolios whether they have a $1 billion drilling budget with many low-risk wells or a $1 billion budget with a few high-risk wells-or something in between.

Companies that understand drilling management and drilling performance systems hold the central key to managing various portfolio types.

Drilling management

A drilling management system defines the purposeful way an organization manages its drilling operations. Some companies adopt a hands-off management style and are content to drill the annual programmed wells to within 30% of the postulated drilling costs.

Other organizations adopt a more-aggressive approach, trying to stay within their drilling budgets, strongly focusing to reduce non-productive time, and operating near or below the industry median dollars per foot. Most E&P companies fall in this category, which is more historic in its approach to drilling management.

Some organizations recognize the financial and opportunistic leverage accrued from more-aggressive management of drilling and purposely develop drilling performance strategies.

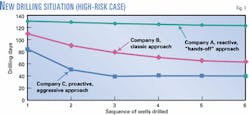

One may discern a company's approach to managing drilling performance from its approach to new drilling situations, whether driven by geology, technology or both. Fig. 1 shows a hypothetical sequence of six high-risk wells drilled by three companies, each unfamiliar with the area.

Company A took a very passive position, simply completing the drilling objectives for each well. It used different consultants and drilling contractors for its wells. One could call this a hands-off management approach.

Company B spent some time planning the first well. Using the same drilling contractor and personnel for all wells, the company achieved better performance based on learning and reduced total drilling time by almost 49 days over six wells.

Adopting a level of planning and operations continuity that afforded continual-learning over the five-well sequence, Company B's exhibited a classic drilling management style.

Company C, demonstrating an aggressive style for planning and fast learning, drilled the initial well 45 days sooner than Company A and 25 days faster than Company B. Company C achieved an operational limit of 40 days per well by the third well and maintained this level for the following three wells.

The total number of drilling days reduced over the six-well sequence reflects the impact of classical and more-aggressive drilling management styles.

Assuming a total spread cost of $50,000/day, over the six wells Company B saved 279 days over Company A, saving $13.9 million-the equivalent of almost five more wells. However, Company C saved $8.9 million more than Company B and $22.85 million more than Company A, the equivalent of four wells more than Company B and 11 wells more than Company A.

Companies with a drilling portfolio in which 30% of the wells are high-risk, learning-curve type wells can save enormous sums. The more expensive the wells are, for example deepwater wells, the more management saves.

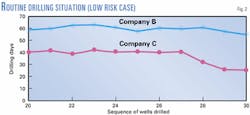

Routine drilling occurs once companies achieve a learning curve level such as the ones depicted for companies B and C. This is the low-risk phase in which managers must emphasize maintaining the high level of performance.

Purposeful interventions further reduce drilling costs, even when companies drill portfolios heavily weighted towards routine, lower risk wells. In Fig. 2, companies B and C constantly drill their 60 and 40-day wells, respectively, for 20 wells. One should note that company A could not afford to continue drilling.

After the 27th well, however, company C further reduced its total drilling days to 25 after a purposeful intervention on the 28th well. Company C could have employed a new technology, new bit type, a better mud system, or a host of planned improvements. Again, this example shows a proactive drilling management style designed to strategically affect drilling costs.

The challenge is for management to get an organization to function proactively and aggressively like Company C, constantly leveraging the drilling performance.

Performance systems

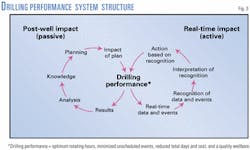

One may consider the diagram of Fig. 3 as an archetype for drilling performance because it depicts a drilling performance system that underpins all drilling organizations' behavior.

Once an organization understands this paradigm it can master the management of drilling performance, hence the drilling management system and the drilling portfolio. In the past, most companies accepted the outcomes of the drilling performance system rather than purposefully managing it.

Readers are left to analyze their own organizations' effectiveness in each component from the following discussion briefly outlining details of the drilling performance system.

One may use causality diagrams to portray dynamic systems. Fig. 3 depicts one interpretation of an overall drilling system related to "drilling performance." The system has two major domains: the post-well impact (the passive part) and the real-time impact (the active part).

The diagram's left side depicts the passive side, after-the-fact analysis of wells drilled, the learning, the conversion of learning to planning, and the dispensing of plans to real-time stakeholders.

The diagram's right side indicates the active side relating to real-time management of drilling operations based on various real-time inputs, reference to drilling plans, and previous learning.

Post well impact

The passive side, after the well is drilled, consists of five elements: gathering drilling results, analyzing results, building knowledge, planning, and transferring knowledge or impacting the plan to the stakeholders (Fig. 3).

Drilling results. Various results such as the daily drilling report or the IADC (International Association of Drilling Contractors) report commonly accompany well drilling. Other reports-electric logs, mud logs, measurement-while-drilling and logging-while-drilling logs (MWD/LWD), bit reports, mud reports, formation tests, and core samples-also document the well's history.

Some wells abound with results with operators adopting a "more is better" philosophy. Other operators question the need for any but the most basic data, providing only the minimum needed to satisfy the well's financial and operational objectives.

For high-risk wells, the maximum amount of data is ideal, especially when learning is paramount to improving drilling performance; low-risk wells need minimal data. Managing information flow is part of managing the drilling performance system.

Results analysis. Companies A, B, and C distinguish themselves from one another by differences in their policies for analyzing past results.

Company A would probably not look at their past results in detail. Company B would have some type of post-operations practice. Company C would have a purposeful system organized to "quality-control" the results, extract trends and deviations from norms, identify problem areas, and note optimum or improving practices.

Most of this work requires analyses tools (databases and specialty software), personal knowledge for evaluating and integrating various results, and documenting well events in such a manner that best enables learning. Comments from the daily drilling report are usually inadequate for this purpose.

Knowledge. Analysis without developing knowledge is useless, but knowledge doesn't automatically come from an analysis.

In fact, the very people who are experts at extracting knowledge from the analysis of results are usually not even involved with the passive side of drilling performance. They are too busy on the active side running operations.

Generally, operational management assigns so little importance to this activity there is little incentive for anyone to build knowledge, which is probably why little purposeful fast learning occurs in the drilling performance system.

The management system faces one of the more difficult aspects critical to improving well planning in the extraction and building of knowledge. In the future, software will help less-experienced drilling personnel extract useful knowledge.

Planning. Plans can be anything from a poster taped to the doghouse wall to a voluminous report detailing every phase of the operation, including lessons learned and probabilities of actions. An organization reflects its overall philosophy about planning's importance and effectiveness by the variation and extent of its plans.

More complex wells require more resources. Critical or complex wells may require as many as 10 man-years of initial planning per well to attain top-tier drilling performance.

Planning is critical to the first well in a learning curve sequence or to a direct (major) intervention to improve routine drilling performance on expensive wells, i.e., how to drill 1,000 m deepwater wells at another cost level. Once drilling performance reaches a constant level, planning requirements decrease.

Plan impact. Few organizations appreciate the need for, or the complexity of, effective transfer of well-crafted plans. A 1/2-day or 1-day pre-spud meeting hardly guarantees proper knowledge transfer to the real-time stakeholders for drilling the next well. This is especially true for high-risk wells.

Lower risk wells can survive a reduced level of plan transfer, but erratic performance in low-risk drilling results from inadequate plan learning and communication, especially when contractors and service companies are changed. Companies should orchestrate some management of the plan's impact around the composition of its support organizations.

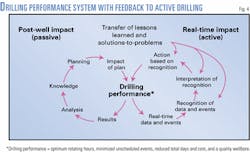

Fig. 4 shows the overall impact that knowledge transfer in the plan has on the real-time drilling or active side of the diagram. Knowledge transfer or impact of this plan greatly influences how effectively the real-time stakeholders recognize events and patterns, interpret what they see, and act.

This is why airlines, the military, and similar organizations spend an inordinate amount of money and time training pilots, ship captains, and military operations personnel on simulators. They recognize the criticality of planning (knowledge, lessons learned) to guarantee operational consistency without unexpected surprises.

The industry needs new tools to improve this aspect of the system, which should be forthcoming in the future, especially with the expected reduction in experienced personnel and the need to use the cadre of outside consultants.

Real time impact, events

Twenty years ago, the drilling recorder, directional driller, and mud logger captured most of the real-time drilling results. As computing capacity increased, digital-based recordings and display hardware became commonplace, especially offshore. MWD and LWD added to the rig information explosion.

Today, some drilling rigs look like mini-mission control centers, with multiple monitors, personal computers, and sophisticated control systems. The most recent era adds high bandwidth and low-cost communications, with data flying across satellites and fiber optic cables to multi-servers and a host of observers.

At first blush, the explosion of affordable, real-time data seemed to be the magic elixir to guarantee drilling performance success. No doubt, the drilling industry has achieved some overall performance improvement certainly with real-time data, which is true with directional and horizontal drilling.

However, over the last few years, it is apparent that the industry's overall drilling performance in total footage drilled per rig has stabilized and if anything has started to decrease.

In the past, drilling personnel directly observed the main real-time data. The more experience that personnel had, the more effective and reliable were their real-time observations. The industry will never again see such an abundance of experienced drilling and service personnel who could read the well as it was being drilled.

Today, millions of bytes of data flood hard drives of computers and monitors with all types of displays flashing at the driller and other personnel. The industry is experiencing output overload.

Like watching six television programs at once, it floods the senses and distracts focus from any one program. How much real-time data is enough and how effective is it in improving and maintaining good drilling performance?

Yet, the effective use of real-time data and information holds a significant potential to offset diminishing numbers and the vanishing experience of drilling personnel. Companies are developing ways to convert it into patterns and event recognition that could lead to another level of rig floor performance.

Event recognition, interpretation

The human mind doesn't interpret large data streams effectively, unless the data is clearly outside of a critical bandwidth. For example, most drilling personnel would respond to a 50-80 bbl mud return gain indicating a kick. They would not likely recognize a kick volume of 10 bbl or less, unless a sophisticated flow-in, flow-out measurement was used and constantly watched.

Like many complex systems where there is a random natural to the environment, there are numerous patterns of data responses for various situations. In the drilling industry's past, human experience interpreted these patterns and conjured some type of explanation. The more events occurring over time, the more the observations took on a higher level of accuracy.

Twenty years ago, the personnel on the rig provided most of the recognition, interpretation, and response. As rig personnel experience levels declined, responsiveness became less.

Today the industry is slowly shifting the job of recognition, interpretation and response of the various real-time patterns to some type of organizational knowledge structure.

An example is the renaissance of companies creating real-time centers bringing real-time data, information and events to a place where a group of experts can focus on the operations, trying to provide some type of interpretation similar to what the experienced rig personnel did in the past.

The lessons learned from previous wells, taken from the passive side where knowledge is extracted, is critical to the recognition, interpretation and response of real-time drilling data, events, and information.

The irony is, however, the very information critical to analysis and knowledge creation on the passive side is generated on the active side, but poorly.

Anyone who has read and studied daily drilling reports understands the problem. The comments are vague, usually not descriptive, and in many cases misleading. It is amazing such an arcane system still prevails for drilling operations.

Today, industrial engineers have designed sophisticated reporting systems for factories that have almost no reliance on the human remembering what happened over the last 24 hr. Plus, it is possible to pull a current report for any segment of the 24-hr period.

There will be modernization of this part of the drilling performance system, only when operating company managements have an overall insight into the importance of real-time recognition and interpretation.

Recognition based action

Few industries put so much financial responsibility, as does the drilling industry, with the man-on-the-brake and the man-in-charge at the rig. The actions taken by these individuals literally save and loose millions of dollars.

Various organizations approach the action part of the drilling performance system in a number of ways. Some companies build from the ground floor.

Rig personnel are usually company hires who go through extensive training and learn what are the company's accepted risk policies. They are groomed to accept more and more responsibility, as they demonstrate increasing expertise and confidence.

Companies purposely expose many of these individuals to varying operations, building their systemic understanding of different drilling and geological systems.

Other organizations maintain a core of company supervisors and use consultants for peak loading. Some organizations are highly dependent on consultants for all the real-time operations.

The human side of drilling will not disappear in the foreseeable future, the same as airline pilots will not disappear. Highly trained personnel will always be in demand at the rig site.

However, improvements in communications will encourage more real-time centers to be setup to support drilling operations at a rig site that can be virtually anywhere.

The constant reduction of drilling operations personnel will force the industry to look elsewhere to maintain or improve the overall real-time drilling performance.

There is no doubt that new decision systems will evolve as well as new training (simulation training) at all levels from the driller to the drilling superintendent and the drilling engineer.

Auto-intelligent equipment systems will replace many of the rig floor man-decisions made today. The next decade will see a major overhaul in this part of the drilling performance systems from the contractor to the operating company.

Drilling management systems

Any company must ask itself whether drilling performance and the management systems manage the company or does the company manage the drilling performance and management systems.

Each company is different, with different organizational structures and policies. What is good for managing one type of drilling portfolio may not be right for another company.

As drilling's share of the overall operating budget becomes less, companies find it less important to manage drilling performance and management systems for the overall performance of the company.

Organizations where drilling is a significant part of the company's spending, can differentiate their performance by managing the drilling management and performance systems.

Companies produce no oil or gas without wells and cannot have wells without drilling. Industry is faced with drilling more wells with less experienced people, in a world that demands a much higher level of environmental maturity by all parties.

The complexities of many of these wells will push the envelope of technology to the limit. Yet, like Captain Lucus and the Hamil brothers, the drilling part of the E&P industry will innovate and continue to produce oil and gas for an energy dependent world.

The author

Keith K. Millheim is manager of operations, technology and planning at Anadarko Petroleum Corp. In most of his 36-year career, he has worked in the private sector as an engineer and consultant for some of the larger E&P companies. Millheim holds a doctorate in mining engineering from the University of Leoben, Austria, as well as an MS in petroleum engineering from the University of Oklahoma. He is widely published and has held leadership positions at numerous professional organizations, most notably SPE.