This article is a late-breaking adjunct to the special report that begins on p. 58.

The push to finally bring Alaskan North Slope natural gas to market is gathering steam.

ANS producers, various pipeline project proponents, and governments in both the US and Canada have in the past year stepped up efforts to bring the long-held dream of monetizing ANS gas to fruition.

The main catalyst for this dramatic turnabout was last year's sharp spike in natural gas prices in the Lower 48 and what it forebode for future gas markets. Many analysts tie the spike to the lack of US gas supply sources and infrastructure amid surging demand and contend that gas prices have moved into a new, higher realm for the foreseeable future.

The effort received an added boost when the administration of President George W. Bush included an ANS gas pipeline project in its proposed national energy plan. Support also has come from the state of Alaska, which has made monetizing ANS gas a top priority and the focus of executive orders and legislation.

And the Canadian federal and affected provincial governments have entered the fray, tying proposals for monetizing Canadian Arctic gas to the ANS initiative. The Mackenzie Delta Producer Group, formed in February 2000 and consisting of ExxonMobil Corp.'s Imperial Oil Ltd., Shell Canada Ltd., and Gulf Canada Resources Ltd. (pending acquisition by Conoco Inc.), are conducting studies of monetizing Mackenzie Delta gas as well, via a $3 billion (Can.) pipeline with a capacity of 800 MMcfd-1 bcfd.

The three principal North Slope producers, BP PLC, Phillips Petroleum Co., and ExxonMobil, earlier this year launched a feasibility study of a proposed pipeline to take ANS gas to the Lower 48.

The $100 million study is expected to be completed by yearend, perhaps even by late fall.

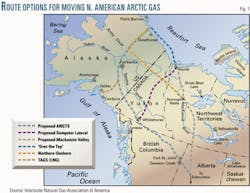

The producers currently are looking at two primary proposed routes: One would follow the Alaska Highway route into Alberta, essentially the same as that already permitted for the long-shelved Alaska Natural Gas Transportation System (ANGTS). The other would extend offshore from Prudhoe Bay into the Beaufort Sea and across to Canada's Mackenzie River delta then down the Mackenzie Valley to existing interconnections in Alberta.

Depending on the route chosen, a pipeline from the North Slope to bring gas ultimately into the Chicago market area is estimated to cost $15-20 billion, says Curtis Thayer, spokesman for the Alaska Gas Producers Pipeline Team, which is heading up the feasibility study.

Proponents of various ANS gas marketing schemes see a window of opportunity for their efforts, thanks to a growing consensus that US gas prices will be sustained above $3/MMbtu for the foreseeable future. Near-term gas prices have recently slipped below that level, and some analysts are ratcheting back their forecasts for the near to mid-term.

However, although antitrust considerations prevent the producers from discussing gas prices with each other, it is not likely that they would be launching another costly feasibility study unless their own gas price forecasts incorporated a threshold that could accommodate an ANS gas project.

As Thayer notes, each of the three producers will have to make its own decision regarding ANS project viability, and top executives on an executive committee representing each of the majors-Phillips CEO Jim Mulva, BP E&P Director Richard Oliver, and ExxonMobil Executive Vice-Pres. Harry Longwell-will make the final decision.

If the three producers give a pipeline project a green light, an initial filing with the US Federal Energy Regulatory Com- mission could come as early as next March, launching the biggest construction project in history.

Questions

Even as the feasibility study seeks to answer questions about technical and economic feasibility about the two pipeline proposals the ANS producers are studying, there remain other questions.

What is not so clear is which of the other competing and intertwined proposals might make the cut (Fig. 1). Another uncertainty is the level of competition from the recent flurry of LNG project proposals directed towards meeting a US gas supply shortfall.

And there remains the question of just what the arrival of such a massive gas supply onto the market will do to the cost structure of gas in North America. Could the combination of arctic gas and multiple LNG projects spawn an oversupply, thus undermining the very price threshold needed to get an ANS gas project off the ground? Further, could a sustained higher gas price spur enough drilling in the Lower 48 and in the Canadian provinces to meet projected North American demand even without frontier gas and LNG?

Such questions about market demand ultimately sank earlier efforts, dating to the 1970s, to monetize ANS gas. ANGTS, the project that many observers still see as the current frontrunner, originated as one of those earlier efforts. It has remained on the shelf awaiting a market need and the right gas price. Both those elements are in place-for now-and many, but not all, market observers see them persisting long enough for a decent return on an ANS gas pipeline.

Market uncertainty will also persist. What may be different this time around is the stance of the North Slope producers. While they are mounting a renewed effort to find and produce more oil on the slope (see related articles beginning on pp. 36 and 58), there is a new focus among slope producers to consider North Slope gas as a viable potential industry in itself.

The state, worrying about the long-term future of the economic benefits from ANS oil, is determined to make ANS gas the foundation of a whole new industry that will benefit it for decades after the contribution from ANS oil has waned.

Meanwhile, there are always the possibilities of regulatory delays, intragovernmental disputes, native claims, and environmentalist lobby lawsuits that could be heaped atop the burden of uncertainty over project economics.

For now, the bigger question is which project(s) will make the cut. It is conceivable that more than one-particularly another one involving Mackenzie Delta gas-could come to the fore. Political pressure may well force such an option into being.

But, again, that begs the question of whether too much frontier gas could hit the market at once, undermining gas prices and threatening the viability of such projects.

In any event, a turning point in this drama is likely to emerge before yearend, when the ANS producers are expected to disclose the results of their feasibility study and make a decision.

The resource

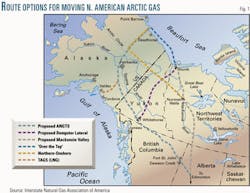

The natural gas resource on Alaska's North Slope is enormous, with proven reserves of 35 tcf in the Prudhoe Bay area alone accounting for as much as 21% of the US total.

ANS producers currently produce 6-8 bcfd of gas that is reinjected into the slope's oil reservoirs as part of pressure maintenance programs. As the fields mature and produce less oil and more gas, the need for and the economic viability of gas reinjection diminishes.

Another 8 tcf of gas reserves has been proven in the Point Thomson Unit, to the east of Prudhoe Bay and home to an estimated 200 million bbl of condensate.

Combined with the proven reserves in the Mackenzie Delta-with an estimated sustainable production of 1-2 bcfd-the proven arctic frontier reserves represents more than 10% of the total North Amer- ican gas reserves base. Potential production from proven arctic reserves alone could meet at least 10% of current North American gas demand, pegged at 74 bcfd in 2000 (Table 1).

That's just what's been proven. US Geological Survey estimates have put the potential natural gas resource on the North Slope alone at as much as 100 tcf.

In addition, ANS gas exploitation would have the added benefit of yielding an estimated 100,000 b/d of NGLs.

The market

From a demand standpoint, most forecasts indicate that the need for Alaskan gas in the Lower 48 will materialize this decade.

The US Energy Information Administration estimates that US demand for natural gas will grow faster than that of any other major fuel source, reaching 35 tcf/year by 2015 and almost 32 tcf by 2020. More than half of this growth will emanate from the electric power generation market, with gas fueling an estimated 900 of the 1,000 new power plants the country will need, says EIA.

In the interim, Lower 48 gas production will grow at a much slower pace over the next 2 decades, EIA predicts. EIA estimates US annual gas output outside Alaska will rise to almost 25 tcf during 2015-20 from 18.3 tcf in 1998.

Cambridge Energy Research Associates earlier this year estimated that incremental growth in demand for natural gas in the US could reach almost 9 bcfd by 2010, assuming economic growth remains steady and prices don't spike out of sight. Of this incremental demand, Canadian sources, notably off the country's eastern coast, could meet more than 2 bcfd. Imports of LNG could account for more than 3 bcfd. But the remainder, about 3.5 bcfd, would be left unfulfilled, and only the Alaska-sourced gas could meet that volume, CERA said.

The Interstate Natural Gas Association of America estimates that, if natural gas prices return to less than $4/MMbtu on an annualized basis by 2003, then the North American natural gas market will grow to 39 tcf in 2020 from 27 tcf in 2000. The US portions of those estimates are 32 tcf and 23 tcf, respectively.

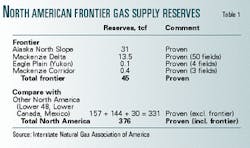

In a study the INGAA Foundation released recently, the association concluded that a frontier gas pipeline could be viable until prices approach $3/MMbtu delivered into Chicago. The study was conducted for INGAA by Houston Energy Group LLC, The Woodlands, Tex., and URS Corp., Maryland Heights, Mo.

The study concluded that a price band of $3-4/MMbtu is needed for overall commercial feasibility of a frontier gas pipeline project (Fig. 2). While $3/MMbtu is seen as a floor for viability, sustained prices above $4/MMbtu would run afoul of the substantial price elasticity in the market-increasingly so with added gas-fired power generation.

"With annual natural gas prices at $4/MMbtu, existing and potential gas customers could switch to other fuel sources, decreasing the economic viability for frontier gas," INGAA's study said. "We also conclude that, at this $3-4 price range, frontier gas is in competition with other gas supply options to serve the North American gas market, such as imports of liquefied natural gas."

But simply delivering ANS gas into the Lower 48 market with a pipeline from the frontier won't be enough, says INGAA. The study concluded that, while there already exists 19 bcfd of takeaway pipeline capacity from Alberta into US and Eastern Canada markets, "additional capacity will be needed in direct proportion to the additional frontier supply delivered into Alberta."

The study found that "substantial new pipeline capacity is needed all the way to the East Coast, including north via Canada over the Great Lakes and south through the US."

Regional natural gas pipeline expansion must also occur into West Coast markets, it concluded.

"Overall, our study supports previous studies that concluded that, in addition to the frontier pipeline system to Alberta, more than 38,000 miles of new natural gas transmission pipelines are needed during the next 15 years to meet market requirements and achieve significant environmental benefits. (The current natural gas pipeline network consists of 270,000 miles.)"

INGAA reckons that, assuming timely approval, frontier natural gas could be flowing into the North American gas grid by 2007. But benefits to the market could predate that, the association said: "Our modeling of the North American market suggests consumers will benefit prior to 2007, because the simple announcement of a pipeline connection to the frontier will create an immediate and long-term stabilizing impact on natural gas prices.

"This results from both the magnitude of the resource and increased customer choice, given the new supply source."

This stabilizing effect again begs the question of what role future gas prices will play in the evolution of Alaskan gas monetization schemes. The US Energy Information Administration forecasts US natural gas prices will edge back down through 2004, as supply ramps up in response to higher prices, then move back up to reach $3.13/Mcf in 2020.

In testimony last September before a US Senate committee, Deputy Energy Sec. T.J. Glauthier indicated that, in the past, a projection of gas prices below $3/Mcf would likely have dampened interest in investing in projects to bring ANS gas to market.

"However, technological progress in construction practices and equipment, in pipe materials, in welding, and in telecommunications are reducing pipeline construction and operating costs," he said. "Companies are now working on thin-walled, high-strength pipe that can lead to smaller-diameter, lower-cost lines. Also, satellite-based communication systems provide real-time operating data at lower cost than traditional telephone lines."

There remain skeptics, however, that any sort of scheme to monetize North Slope gas is viable.

In an interview with OGJ earlier this year, leading gas analyst Arlon Tussing, of Seattle, claimed that, "Unless you're convinced there has been a major, permanent, structural shift [in the fundamentals of the US gas market, then]ellipsethere's no basis for a gas pipeline either to the Lower 48 or to an LNG terminal (OGJ, Feb. 12, 2001, p. 74)."

Project costs

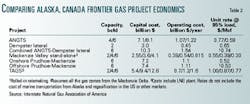

INGAA studied the various frontier pipeline project proposals being considered and applied a generalized "rule-of-thumb" approach to provide first-level cost comparisons of the various options (Table 2).

The INGAA study made the following assumptions about a frontier pipeline, in that it would:

- Extend to Alberta-British Columbia (or to Valdez, Alas., in the case of an LNG project).

- Cost $100,000/in.-mile onshore and $150,000/in.-mile offshore, including compression, conditioning plant at source, line pack, meter stations, SCADA, remote monitoring, and communications, among other elements.

- Have pipeline diameters for respective throughput capacities of 30 in. for 2 bcfd, 42 in. for 4 bcfd, and 48 in. for 6 bcfd.

- Have an annual operating cost equal to 15% of upfront capital cost that includes a return on capital and actual operating costs.

- Have an annual throughput, with a 95% capacity load factor, of 695 bcf/year for 2 bcfd, 1.39 tcf/year for 4 bcfd, and 2.08 tcf/year for 6 bcfd.

"These cost assumptions and capacity assumptions are higher than current best practice and attempt to take into consideration the unique requirements and challenges of the frontier," INGAA said.

ANGTS

The forerunner of all ANS gas pipeline projects is ANGTS, which received regulatory approvals in the 1970s.

This line would parallel the Trans-Alaska Pipeline System from the North Slope to Fairbanks, then veer east along the Alaska Highway through Yukon Territory, northern British Columbia, and into Alberta.

The project was given its name as designated by President Jimmy Carter in September 1977, in order to place it under a streamlined certification process under the 1976 Alaska Natural Gas Transportation Act. President Carter chose the project among three ANS gas monetization proposals competing for certification before the then-Federal Power Commission. A joint session of Congress also approved the project.

ANGTS originally called for a joint US-Canadian onshore pipeline spanning almost 5,000 miles that could transport 1.5-2.5 bcfd of ANS gas to the Lower 48.

Part of the original ANGTS was built in the years that followed. The so-called "prebuild" segments extend 2,675 miles along two legs from Alberta into the Lower 48-to the Chicago hub and to California. About 3.3 bcfd of Canadian gas moves to these markets through the prebuild legs, which were completed in 1982. They entail 650 miles of 36 and 42-in. pipeline from Caroline, Alta., to Monchy, Sask., and Kingsgate, BC, on the US border.

The statutory framework governing ANGTS, which includes the relevant agreements between the US and Canadian governments, still exists. However, the environmental reviews are more than 25 years old.

The permits for ANGTS, developed during the 1970s and 1980s by a consortium of US and Canadian pipeline firms called the Alaskan Northwest Natural Gas Transporta- tion Co. (ANNGTC), were acquired by Calgary-based Foothills Pipe Lines Ltd. Foothills is owned by units of TransCanada PipeLines Ltd. and Westcoast Energy Ltd., both of Calgary. The Canadian government has designated Foothills to own and operate the Canadian segment of ANGTS.

Although state and federal rights-of-way were applied for in 1981, the project has largely remained on the shelf since 1982 for lack of market. But in March of this year, ANNGTC applied to the the Alaska State Pipeline Coordinator (ASPC) to continue its application for a pipeline ROW on state lands. The state ROW covers 235 miles, while the federal ROW for ANGTS covers over 400 miles. Foothills, on behalf of ANNGTC, late last month signed a memorandum of understanding with ASPC to complete its review of the state ROW.

'Over the top'

Certainly the most controversial proposal to deliver North Slope gas to market has been the route extending offshore from Prudhoe Bay into the Beaufort Sea and 370 miles to the Mackenzie Delta.

This 42-in. pipeline presumably would link with an onshore pipeline running along the Mackenzie Valley into northern Alberta. It is backed by a Houston-based group, Arctic Resources Co., headed by former Enron Oil & Gas Co. Chairman Forrest Hoglund.

Late last month, a Canadian Coast Guard vessel headed into the Beaufort with a group of of scientists aboard to study sea ice and seabed conditions along the proposed offshore route. It is part of a multiyear project, but initial data are expected to be available by spring 2002.

ARC contends the so-called "over-the-top" route is the cheapest because of its shorter length and thus would bring the producers significantly greater netbacks.

However, there are huge technical and environmental unknowns associated with this project. While BP recently laid the first buried subsea arctic oil pipeline, from Northstar oil field in the Beaufort, to shore, there is no precedent for a buried subsea gas pipeline of such scope and operating under such high pressure. The proposal has aroused the ire of environmental groups and North Slope native groups, as well as Alaska's state government.

TAGS

The Trans-Alaska Gas System is another competing proposal to monetize ANS gas.

Proposed in 1987, it envisions delivery of ANS gas via an 800 mile, 42-in. chilled and buried pipeline paralleling TAPS all the way to tidewater, at Anderson Bay just 3 miles west of the TAPS terminal at Valdez.

There, the gas would be liquefied for export to Asian markets, notably Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan. The originally estimated project cost of $12 billion includes the TAGS line, the liquefaction complex, and 12-15 LNG carriers. Exports would total 660 bcf/year for 25 years, for a total of 16.5 tcf.

It is sponsored by Anchorage-based Yukon Pacific Corp., founded by former Alaska Gov. Walter Hickel. CSX Corp., Richmond, Va., holds a majority interest in YPC.

Over the years, YPC has secured environmental approvals, LNG export approv- als, and federal and state ROW and site construction accords for the project, but it, too, has languished for lack of market.

In May 1988, the Alaska legislature approved a bill introduced by Gov. Tony Knowles that, among other goals, sought to spur formation of a sponsor group for the project. ARCO Alaska Inc., Phillips, Foothills, YPC, and Japan's Marubeni Corp. signed a formal sponsor group agreement later that year. (ARCO was subsequently acquired by BP, which later sold the ARCO Alaska assets to Phillips.)

The sponsor group completed a first-stage feasibility study that assessed a 7 million tonne/year, $7 billion project that could site the liquefaction and export facilities either near Valdez or near the existing LNG export facilities on the Kenai Peninsula operated by Phillips.

Presumably, the new plant would incorporate some of the existing Kenai facilities. Phillips has exported LNG to Japan from its Kenai complex for over 30 years. In April 1999, Kenai LNG sales to Japan were extended through March 2009.

A second-stage feasibility study, currently under way and originally projected to be completed in second half 2001, would focus on fine-tuning project economic competitiveness.

Since its inception, the TAGS project has not been able to secure supply agreements with customers in Asia. In addition to competition from Australian, Indonesian, and Malaysian LNG exporters, there looms on the horizon another major competitor to TAGS for the Asian LNG market. A group led by Royal Dutch/Shell last month announced it was greenlighting plans for a massive new LNG export complex on Russia's Sakhalin Island, targeting the Asian market.

YPC reportedly has been also considering LNG sales to the US West Coast-target market of the original, 1970s-vintage Alaskan LNG export scheme that competed with ANGTS and another pipeline proposal-via a recently proposed LNG terminal along the western coast of Mexico's Baja California peninsula.

Other proposals

Several other pipeline proposals have been put forth to move arctic frontier gas to market in North America.

The so-called Dempster Lateral entails running a spur from the Alaska Highway pipeline north from Gordondale, Alas., to Inuvik, NWT. It would follow the Demp- ster Highway for about 1,025 miles. The 2 bcfd, 30-in. line would presumably tie into the Canadian grid at Whitehorse, NWT.

Apart from any Alaska-based pipelines, there is also consideration of a stand-alone Mackenzie Valley gas pipeline that would extend 850 miles along the Mackenzie River Valley in the Northwest Territories into Alberta.

Another Mackenzie Valley route would pick up ANS gas via a 600-mile overland route from Alaska that passes south of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge before entering Canada and tying into a pipeline that originates at the Mackenzie Delta. The Alaska-Mackenzie leg would entail a 42-in. pipeline extending 850 miles. If the two pipelines are not coordinated, then there is the prospect of laying two parallel, 30-in. lines from the Mackenzie Delta south in legs of 850 miles and 700 miles.

Still another ANS gas monetization option would not necessarily involve a gas pipeline at all, and it still could be in prospect even with a gas pipeline. BP, with a 30% stake in 35 tcf of North Slope gas reserves, is constructing an $86 million gas-to-liquids test facility at Nikiski, south of Anchorage. The pilot plant is expected to be completed in early 2002, to test GTL technology for use in a possible North Slope commercial-scale plant.

Producers' pipeline study

While the proponents of various schemes to deliver ANS gas to market jockey around for position, the ANS producers' group is really just considering two proposals: the "over-the-top" route and the Alaska Highway route to existing or newbuild pipeline facilities in Canada.

The proposal eyed in the feasibility study for the overland route is even more ambitious than the original ANGTS proposal: a 48-in. pipeline, completely chilled and buried for the length of its route and operating at a line pressure of 2,400 psi, extending more than 3,600 miles-"longer than the Great Wall of China," Thayer noted, adding, "and with expansion capabilities."

The pipeline study team has mustered more than 100 employees from the three companies and enlisted the help of another 500 employees from contractors in studying the commercial, environmental, and technical viability of such a project.

The study focuses only on these two routes without taking into consideration any linking pipelines in Canada-basing the economic viability of the project solely on ANS gas reserves.

As it stands now, the tentative time frame for either pipeline route calls for a permitting period of 18 months to 2 years and a preliminary engineering span of 1-2 years. Assuming the industry has the capability to produce the volume of specialized high-strength steel required for a pipeline of this magnitude, construction could get under way in another 2-3 years. Ultimately, an ANS pipeline could start up in 7-9 years, with gas reaching Lower 48 markets by the end of the decade, according to Thayer.

Comparing proposals

As much as almost everyone-save some of the more-extreme environmental lobby groups, though some environmental groups favor it-wants to see an Alaskan gas pipeline of some sort, the controversy over which route is best isn't going to die down soon.

Foothills regularly touts the ANGTS project as far out in front of everyone else.

"One thing that everyone in Washing- ton and Anchorage agrees on is that getting North Slope gas to the Lower 48 is a priority, and our approved route along the Alaska Highway through Canada can deliver that gas 2-3 years earlier than any greenfield project," said Foothills Vice-Pres. John Ellwood. "We have invested hundreds of millions of dollars to advance this project, and that has enhanced our ability to deliver Alaska gas to the Lower 48."

While many others see ANGTS as the frontrunner as well, the reality of the situation is not as cut-and-dried for the producers.

"Yes, Foothills still has the permits, but there will be a financial cost," Thayer noted. "Those permits are not going to be free." He also contends that some permitting efforts will need to be revisited: "An environmental impact statement made 25 years ago won't stand today."

On the other hand, Thayer contends that an early look at the two projects' respective costs suggests that the "over-the-top" route will come in at the lower end of the $15-20 billion projected costs: "It does appear to be cheaper."

Alaska Republican Rep. Don Young recently responded to that notion by saying, "It doesn't matter, if you can't get it built."

Young made the comment shortly after legislation was introduced in the US House of Representatives late last month banning construction of a gas pipeline off northern Alaska.

That follows approval of Alaskan state legislation earlier this year banning construction of a gas pipeline in northern state waters.

Gov. Knowles and the state legislature have been adamant in opposition to an offshore route, with the governor adopting a paraphrase of an old adage: "My way is the highway," referring to the Alaska Highway route.

While Thayer contends that "ironically, the northern route allows a higher netback to the state-about $100 million/ year," the governor cites the multiplier effects of a pipeline staying within Alaska's territory:

- The direct multiplier effect of billions of dollars invested within Alaska's borders.

- Revenues to the state of billions of dollars from pipeline fees.

- Access by Alaskan communities to new gas supplies (concerns are mounting in fast-growing South-Central Alaska over dwindling Cook Inlet gas supplies).

- Feedstock and fuel for new industries.

- Economics of sustaining new LNG and GTL projects.

- Domino effects on other upstream, midstream, and downstream potential.

Thayer has little use for the political crossfire, contending that there was no point to the state's ban on offshore gas pipeline construction "without having all the facts first, all the information on costs, etc.," before deciding to favor one route over another.

"The marketplace will decideellipsethe question of which route is better," he said. If the producers do opt for the offshore route, he noted, then "Alaskans will have to just make a decision if they want a gas pipeline or notellipseSo they might want to revisit that legislation."

Complicating this dispute was the Canadian federal government late last month, which stepped in on the side of the Northwest Territories, which has complained that an Alaska Highway project could delay the development of Canadian Arctic gas for 10-15 years, depriving aboriginal groups, who hold most of the land in the territory, of the economic benefits from gas production and a pipeline.

Prime Minister Jean Chretien called for the ANS producers to adopt the "over-the-top" route, and other Canadian officials threatened to challenge the Alaska offshore pipeline construction ban if it is implemented.

Foothills insists there is a third option: a "two-pipeline solution" that would take in an Alaska Highway pipeline and a Mackenzie Valley pipeline.

In a May 11 presentation to the Arctic Institute of North America in Calgary, Foothills Vice-Pres. Harry Hobbs took issue with concerns in Canada that an Alaska Highway route would delay Mackenzie Delta gas monetization.

Hobbs contends that a projected incremental North America demand of 30 tcf/year by 2010-which he said may be a conservative estimate-can readily accommodate both ANS and Mackenzie Delta gas.

"...While the timing of each gas supply source will be dependent upon its own circumstances-commercial, political, and regulatory, among others-both pipelines will have to flow, and the market will want both supply sources as soon as possible," he said.

In the final analysis, until the producers' ANS pipeline study is completed, all the current controversy really boils down to conjecture and political rhetoric, Thayer contends.

"Politics can't make this deal happen," he warned, "but it sure can kill it."