Pipeline owners must reassess utility of undivided-interest ownership

Undivided interest joint-venture pipelines work best in high entry-barrier markets with cost-focused owners.

Such a joint venture can be defined as a form of co-ownership in which each owner has a share or title in a property as if he were sole owner of that share or title.

Over the long economic life of a pipeline, however, cost and profit parameters among the owners inevitably diverge, often shifting toward profit emphasis rather than cost control.

When competitive pressures in the venture threaten the asset's viability, conversion to joint-venture formats more compatible with profit centers can extend the life of the joint venture.

If such conversions are not possible, adjustments to cost allocation may smooth conflicts and sustain a longer asset life. Inasmuch as domestic and global markets are becoming more open, undivided-interest joint ventures will find less application in the future.

Joint-venture pipelines

The value in economies of scale remains as strong as ever, and building scale rapidly by forming joint ventures has been a favorite tool. Larger scale lowers per-unit costs and risk and enlarges market power.

Merging two or more interests into a common, or joint, venture can create scale changes far exceeding any achievable through normal business growth. For enterprises with large fixed costs, such as pipelines, such scale changes produce nearly commensurate drops in unit costs and can transform a marginal project into a solid winner.

It is not surprising, therefore, to see use of joint-venture pipelines in which economic scale has particular advantages, such as offshore with its high cost and risk, or large, remote, and technically difficult pipelines such as the Trans Alaska Pipeline.

Joint-venture legal formats

Unlike mergers that combine several owners into one entity, joint ventures create a new entity without subsuming the original companies. Joint ventures therefore have multiple parties involved with the common asset, each governed by corporate by-laws, fiduciary responsibilities, and other agreements separate from and in addition to those of the common asset.

If separate entities exist, it is likely that separate competitive goals also exist. Thus, the key to the success of any joint venture is aligning the separate owner goals with the common asset despite potential outside conflicts. If the owners cannot work together, the business becomes so paralyzed and cost ridden as to defeat the benefits of the venture.

To ensure the best alignment of interest, joint-venture contracts provide explicit instructions for every act of the common business, including how decisions are made, who can operate the assets, guarantees for liabilities, division of profits, sharing of costs, dissolution of the venture, and final disposition of the asset.

Carefully prescribing the actions of the owners in governing the common asset makes it possible to minimize conflicts and optimize alignment. As long as owners remain divided into separate entities, however, competitive interests will always remain regardless of how precise or detailed the joint-venture contracts.

Paramount to designing joint-venture contracts is deciding what legal format the common asset will assume. Joint-venture formats include simple partnership, stock, limited-liability partnership, limited-liability company, and undivided interest.

Each format has implications for liabilities, profits, and governance. Owners, however, must often focus on two features: protection from liability and tax efficiency.

A simple partnership does not create a new legal entity but merely divides liabilities and profits among the partners. Without the legal barrier of a new entity, partners cannot be shielded from joint-venture liabilities. But also, without a new entity, no new taxes are incurred.

A stock company is a separate corporation that can limit transfer of its liabilities across its corporate barrier but is subject to corporate taxes. If profits are distributed as dividends, owners are doubly taxed, once in the corporate joint venture and again for dividend income.

A limited liability partnership (LLP) keeps the simple partnership advantage of avoiding corporate taxes but has a general partner which accepts liability, thereby limiting liability among the common partners.

The limited liability company (LLC) is the newest form of corporation. It has a corporate barrier to limit transfer of liability but avoids double taxation by distributing profits as a partnership.

Undivided-interest joint ventures

Undivided interest is the most unusual format for joint ventures. For an undivided-interest asset, each owner's interest in the asset remains separate and distinct (undivided) from the other interests.

Unlike partnerships or corporations that define a single common asset with rules that distribute income, undivided-interest systems separate common facilities into multiple assets with rules that allocate use and costs.

Without a common entity, undivided-interests formats suffer no additional taxes. Without a common entity, the corporate barrier between each owner remains in place to control liabilities. Each owner is subject to only its share of total liabilities, assuming all owners remain solvent.

Ownership in an apartment building can be used as an example of the difference between undivided interest and other forms of joint ventures. It is possible for the building to be a joint venture wherein only one entity owns all of the apartments and the joint-venture parties own pieces of the entity in the form of stock or partnership share.

In this case, the entire building is run as a single asset, with only one set of books and with earnings divided according to ownership share in the venture.

It is also possible for the building to become an undivided-interest joint venture by being converted into condominiums. Each apartment can be owned by a different corporate or individual entity, and each owner can live in the unit or lease it out for profit independently of other owners.

Each apartment has its own corporate governance, books, prices, and earnings that are separate from the other owners. Each apartment owner, however, must share (allocate among the owners) the expense and capital costs of the total building and follow rules controlling common grounds and facilities.

Undivided-interest pipeline

If this analogy is to be applied to an undivided-interest pipeline, the overall pipeline must be viewed as a collection of smaller pipelines, just as the apartment building is a collection of individual apartments. Each owner's piece of the asset would be defined by capacity limitations.

Owner A might have 25% undivided-interest ownership in a pipeline with a total throughput capacity of 100,000 b/d. Owner A would therefore have an undivided-interest equivalent to a 25,000-b/d pipeline. Owner A would publish its own tariff, have separate nominations and shippers, and collect revenue separately from all other owners.

On paper, each owner would appear to have a separate pipeline, but in reality all owners would share origin, injection, delivery points, pumps, tanks, and other facilities in the overall pipeline. There is usually only one operator of the physical facilities, often the largest owner, and the common costs of the pipeline would be allocated among all owners in a manner dictated by the joint-venture agreements.

Joint-venture formats

Considering only the owner-alignment implication of a joint venture leads to the conclusion that the undivided-interest format is the least desirable of the choices. All the other formats require the common entity to make a profit before any owner can receive its share.

As profit entails a combination of elements (such as capital, expense, and revenue), owners in these formats must also reach a degree of consensus for each of the profit elements to be successful.

The end result is that owners in non-undivided-interest formats must be strongly aligned in most elements of the business to be profitable.

In undivided-interest assets, there are no common profit entities. Because each owner must collect its own revenues, undivided-interest formats ensure competition among owners rather than alignment. Ironically, the result is a venture more "competitive" than "joint."

By the owners' sharing the same physical facility, the undivided-interest format guarantees each that owner will have nearly identical competing pipelines with the same origins, destinations, operating parameters, and capital basis.

An undivided-interest owner must therefore compete in an environment in which his ability to differentiate his services is extremely limited and his competitors know his operating costs and investment plans.

Undivided-interest pipelines offer some compensation for their difficult competitive position. First, with separate profit sources, undivided interest provides greater individual control for the owner. Owners remain separate entities and can pursue individual business strategies apart from the other owners.

Pricing, customer focus, and alignment with other assets are individual owner decisions. Competitive interests are not compromised through shared data or forecasts. Owners only have to agree on pipeline operating, expense, and capital issues. For simple day-to-day operations, such agreement is easily achieved because most businesses believe, obviously, that lower costs are better than higher.

Secondly, undivided-interest formats offer the same economies of scale in unit costs as the other formats. By joining together, undivided-interest owners can enjoy the greater efficiencies of a larger pipeline rather than maintaining many smaller pipelines.

Pipeline operation has many fixed costs unrelated to throughput, such as management, right-of-way and station maintenance, and repair crews. It will take almost the same number of management, pipeline gang, and maintenance personnel to run a 200-mile, four station, 50,000-b/d pipeline as a 200 mile, four station, 200,000-b/d pipeline.

Pipeline construction costs also have many components not directly proportional to capacity, such as mobilization, permitting, right-of-way, engineering, and lay costs. By spreading these capital costs over 200,000-b/d rather that 50,000-b/d, the larger pipeline will have greater potential for improved returns.

Application

These insights into undivided-interest joint ventures allow consideration of where this format would be most useful. With its low competitive advantage, it would not be very effective in an unrestricted market where many other pipeline competitors exist. Therefore, the best competitive application would be in markets with high entry barriers.

Examples would be an offshore crude reservoir with barriers of cost, risk, and economic life, or an onshore, large, and expensive trunkline whose economies of scale cannot be matched.

The separation of profit centers in undivided joint ventures allows alignment of each owner's pipeline share with other interests upstream or downstream of the pipeline. The undivided-interest pipeline share can be integrated with other profit centers controlled by the same owner without compromising confidential data or competitive positions of the non-pipeline profit center.

An integrated oil company might use an undivided-interest format to tie its crude oil production to a refinery since it allows an integrated transportation pricing strategy different from the other pipeline owners.

Integrated owners are less affected by the competitive weakness of the undivided-interest format because transportation profits are only a part of the total integrated value chain. If an owner has crude oil production moving into its own pipeline share, then to its own ships, and finally to its own refinery, the pipeline portion of costs and profits affect the bottom line in a smaller proportion.

Further, because no integrated profit is produced when the owner ships on its own pipeline share, the significance of the pipeline profit center lessens as the owner's volumes increase.

If all of the shipments on a pipeline come from its owner, there would be no integrated profit at all. The owner would pay the pipeline profit to itself. In this case, the undivided-interest pipeline becomes a cost center, rather than a profit center, in the integrated chain of assets.

A cost-center focus is more compatible with an undivided-interest format because it emphasizes the format's natural cost alignment of the owners rather than the profit divergence.

This separation of profit centers also influences costs because it requires separate management organizations for each owner rather than one common management group for the entire pipeline.

These multiple management groups prevent undivided-interest formats from providing as much overhead savings as the other formats, so that undivided interest would not be used where overhead costs are a significant part of the business.

It would be more likely that an undivided-interest owner would already have a pipeline management group in place, reducing the new asset's management costs to incremental values.

Table 1 lists the formats of some of the larger US pipeline systems.

Undivided-interest lines: problem

Undivided-interest joint ventures in the oil industry were first associated with crude oil production facilities. Undivided-interest production assets captured the cost advantages of a joint venture but allowed individual owner control of the essential profit center, the sale of oil.

Because it is usually in the best interest of each owner to maximize production volume and minimize costs, the operating objectives of the production joint venture are aligned. If all the crude production is of one type at the location, the market price of the oil is also fairly well aligned. Thus, the separation of profit centers in the undivided-interest format does not necessarily result in strong competition between the producers.

The operational alignment, equal per-unit costs, and common market price effectively moot competition at the wellhead, thereby increasing cooperation. Competition is not lost but shifted more downstream from the wellhead to oil marketing and refining assets.

Adding a pipeline to the production facilities will not affect the alignment among owners as long as the basic production joint-venture parameters are unchanged. If the pipeline is sized to fit the single reservoir volumes, owners would have pipeline capacity needs similar to their production ownership, likely resulting in equal percentage ownerships in both production and pipeline.

If owners have equal shares of production and pipeline, unit costs remain equal among the owners, and if there were only one crude type and delivery point, market prices would also be equal. With no competitive advantage to be gained at the delivery point of the pipeline, the undivided-interest format disadvantage is muted.

Regardless of the initial alignment of operating parameters, however, production and pipeline assets are fundamentally different and it is inevitable that operating parameters will diverge. Principal differences driving this divergence are asset economic life, market access, and government regulation.

Pipelines are extremely long-lived assets. Despite their poorer technology, some of the pipelines built in the early 1900s are still operating today. Using the latest corrosion protection and inspection techniques, pipelines have essentially unlimited physical life when appropriate maintenance is used.

In contrast, crude oil production reservoirs are depleting assets. Even though a large reservoir may last 20-50 years, the operational goal is exactly the opposite of a pipeline: to maximize production volume and shorten production life as much as possible without harming the overall recovery of oil.

As a reservoir depletes, it is in the business interest of the production owners to replace their dwindling revenues with other sources of oil from other reservoirs. Since it is unlikely that the new production will have identical owners with identical shares of identical oil, the new reservoirs would change operational parameters, market price, and unit costs. With these changes comes heightened competition among owners.

Pipelines and production facilities also contrast in market access. A reservoir is essentially a point source limited to one small geographic market within its immediate vicinity. In the early days, refineries and oil fields were right next to each other. Pipelines, however, stretch hundreds of miles and are specifically designed to reach across geographic markets.

This cross-market reach greatly increases the probability of finding other connections and delivery points for the pipeline, each representing new profit opportunities. With each new profit opportunity comes a new competitive conflict.

Finally, in contrast to production facilities, pipelines in the US are subject to common-carrier regulations that may require open access to the line. Depending on circumstances, owners may be unable to prevent new connections to the pipeline by either non-pipeline owners or existing joint-venture participants. Such connections would ensure divergence of unit costs and competitive interests.

So, with the decline of the original reservoir comes the decline of the original alignment among owners. If the pipeline is to remain viable, new reservoirs and connections must be found. These changes bring new profit centers and likely new competitive conflicts among owners.

With enough time and opportunity, it is possible for the owners to evolve from nearly uniform businesses with similar interests to entities with drastically opposing views, such as refiners and producers or carriers and shippers. Such owners in a joint venture would find cooperation difficult, if not impossible, as they try to meet their opposing profit goals.

Conversion

If incentives remain to keep the joint venture working, an obvious adjustment to unworkable competitive positions among undivided-interest owners is to convert to a more favorable format, such as a partnership or stock company. In practice, conversions have been made to LLPs or LLCs to avoid double taxation and shared liabilities.

Conversion is not easy because full conversion requires owners with potentially conflicting goals to agree unanimously to the restructuring. The two largest hurdles are usually the following:

- Determining what value each undivided-interest share contributes to the new joint venture.

- Governance (or voting rights).

There are also significant secondary issues such as taxes, tariffs, and litigation carry over.

If each undivided interest in the pipeline has different profitability levels, its profit contribution to the new partnership will not be commensurate with its percent of undivided-interest ownership.

A 25% share of the pipeline that is only shipping half of its capacity will contribute only 12.5% to the new joint-venture earnings, assuming equal per-unit profit margins. A 15% shareowner that is filled to capacity would object to letting the 25% owner keep 25% of the new profits if it only contributed 12.5%.

The basis of governance is also prickly. Undivided-interest owners had unilateral control of pricing and other strategic company issues, while the new joint venture must have one strategy for all. How the new actions and strategies are decided becomes critical to owners with opposing views. A simple majority may be too coarse, but a supermajority vote impractical.

Joint ventures with many owners with nearly equal ownership can use simple voting schemes since each vote has nearly equal impact on results. Joint ventures with few owners or owners with large differences in ownership, however, would need more complicated voting schemes to ensure equitable results.

If the owners' tax bases vary, forming the new joint venture could cause a taxable event, which may add significant cost to the effort. The tax-basis variations would likely come from different assumptions on tax depreciation of the asset. Also, if tariff assumptions or methodologies vary, there could be effects to the joint-venture single tariff. And, the threat of over hanging litigation must be worked out.

With so many issues, total conversion is a difficult task at best and an impossible one if owners have strongly divergent views.

If the conversion is attempted early in the decline of an undivided-interest asset, there is likely greater alignment among owners and a greater chance of success. If conversion is attempted very late in the decline of the venture, the threat of large economic loss to all owners might overcome the residual value of remaining a joint venture, prompting some owners to prefer to cut losses rather than extend them.

The easiest conversions are those with the fewest choices, usually involving the threat of zero profit and the need to cut costs to extend economic life. If full conversion is too difficult, a partial conversion of those owners inclined to agree to a new venture format could be attempted and the remaining owners could keep their undivided-interest shares.

Adjustments

If conversion to another format is not feasible, adjustments to the undivided interest joint-venture contracts may provide means to mimic some of the advantages of other formats.

The competitive alignment found in partnerships and stock companies derives from the cost and profit parameters of the asset being shared uniformly by all owners. There is only one set of books, one set of markets, one revenue stream, and one strategy for all.

In undivided interests, there may be only one common asset and set of markets, but there are isolated revenue streams, allocated costs, and individual strategies for each owner. The isolated revenue streams and allocated costs lead to unit cost and profit variance among the owners, but the common physical asset and market usually allow only one successful strategy.

Without parity among the owners' unit costs and profits, not every owner can implement the most successful strategy and may be resigned to a failed business.

As long as owners remain separate legal entities, profits cannot be directly shared among them legally. Revenue must be exchanged for services or products to avoid anti-trust action. Cost allocation, however, can be adjusted to affect profits indirectly.

Joint ventures typically separate costs into capital, fixed operating, and variable operating costs and then define an allocation methodology to distribute these costs among the owners. A common methodology is each owner pays its asset percentage ownership share of capital and fixed operating costs, and its percentage of throughput share of variable operating costs.

An owner with 25% share in the asset and 15% share of total throughput would pay 25% of capital and fixed costs and 15% of variable costs. Pipelines have high fixed costs, often in the 60-80% range, consisting of overhead, property taxes, depreciation, and maintenance labor, for example.

Variable costs are principally power (electric or fuel) and possibly small amounts of additives, such as corrosion inhibitor or drag reducing additives. Since each joint-venture owner keeps its own set of books, depreciation is not an allocated expense, but calculated by each owner based on its individual assumptions and book values.

This common allocation method produces equal per-unit operating costs ($/barrel of throughput) for all owners only when all owners' percentage ownership shares in the asset are equal to their percentage of total throughput.

When this is true, each owner's per-unit costs equal the total system unit costs. If an owner has a higher share of throughput than asset, its unit costs are lower than the system average.

Conversely, a lower share of throughput than asset ownership produces unit costs higher than the system average. The competitive consequence of this allocation is an under shipper (higher asset share than throughput share) must compete in the same market with the same physical asset, but with higher per unit costs. Even worse, its competitors can reasonable estimate these higher costs if throughputs are known.

In a strongly competitive market (much more pipeline capacity supply than demand), such an under shipper could never win a price war and would likely be forced out of business.

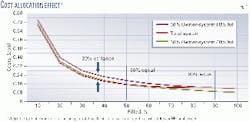

Fig. 1 illustrates this cost allocation effect for an owner with 50% interest in a joint-venture pipeline. The "50% Owner-system 50% full" curve represents owner per-barrel costs as the owner capacity percent fill varies 0-100% and the total system capacity remains filled at 50%.

When the owner is less than 50% filled, its costs are slightly more than the system cost. At the point where owner percentage fill equals the systems 50% filled capacity, the costs are equal. When the owner's percent of capacity filled is higher than the total system's 50% filled capacity, its per-unit costs are less than the system cost.

A curve is also plotted for a 50% owner with the total system capacity filled to 90%. Again, per-unit costs for the system and owner are equal when the percent of capacity filled is equal. Variance between per unit costs increases as the difference between system and individual owner percent fill increases.

In this example, when the system is 90% full, an individual owner per-unit cost can be as much as 20% greater than the system cost.

If the allocation method were adjusted to distribute all operating costs based only on each owner's throughput percentage, all owners' per-unit costs would be equal to the system per-unit cost all of the time.

Operating costs would act in the manner of a LLP or LLC. An owner with zero throughput would pay zero operating cost but would still have capital cost allocation. With near parity in per-unit operating cost, competition could be better sustained.

Other allocation schemes could be created, but regardless of the scheme, the undivided-interest format remains disadvantaged when compared to competitive alignment in other joint-venture formats.

Conversion to another format would still give more relief than allocation adjustment.

The author

Randy R. Irvin has been an independent consultant since late 2000 after spending 25 years with Mobil Pipe Line Co. He began in the company's instrumentation and electrical engineering group and progressed through field and operations positions that included central Texas crude and LPG facilities, Olympic Pipeline, offshore Gulf of Mexico production, and Mobil's East Coast products pipeline systems.

For the final 10 years with Mobil, Irvin worked in planning and joint ventures and was the principal business analyst for Mobil's North American crude oil joint venture pipelines. He has served as an officer and director of several companies, including Mobil Alaska Pipe Line Co., Mobil Eugene Island Pipeline Co., and Mobil Pipe Line Co., and as a trustee of the Trans Alaska Pipeline Liability Fund. Irvin holds a BS in electrical engineering from Texas A&M University, College Station.