Asian economies have recovered from a severe downturn in 1998 and em barked on self-sustained growth that has resulted in continuing, substantial growth in energy demand.

This demand has again raised concerns about energy security in the re gion. Specifically, dependence on oil imports and environmental concerns over coal and nuclear power have created a new atmosphere for strong LNG demand.

Prospects for increasing LNG demand depend heavily on the contract structure. With deregulation and privatization picking up momentum in the Asia-Pacific region, however, most utilities are wary of long-term, take-or-pay contracts.

Thus, while LNG demand could be or should be larger, the contract structure is holding it back. At the same time, regional LNG suppliers are trying to get buyers committed at any cost.

Asian energy demand

Nearly all developing countries in the Asia-Pacific region are looking at an average annual gross domestic product growth rate of more than 5% through 2001. This bodes well for growth in energy demand, especially for LNG.

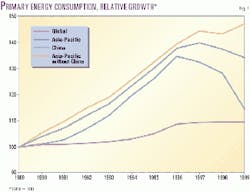

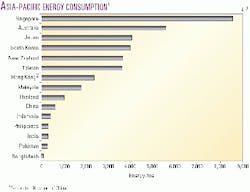

In 1999, total primary energy demand in Asia-Pacific declined by 2.3%, caused by a decrease of as much as 10.7% in total primary energy use in China (Fig. 1). The largest primary energy consumer in the Asia-Pacific region, China accounts for about one third of the regional demand and one third of the global demand for coal.

Oil and gas consumption

Consumption of oil and natural gas in the Asia-Pacific region has been increasing rapidly. In general, more oil and gas use increases the efficiency of the economic sectors vis-a-vis energy consumption in China, which heavily depends on coal.

Economic growth in China is robust despite the decline in primary energy consumption. During 1997-99, primary energy consumption declined by 4.3%/

year, while the official GDP growth averaged 7.9%/year. This huge discrepancy suggests that the official GDP growth rates reported by the Chinese government are overstated by as much as 3-4% annually.

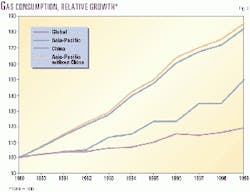

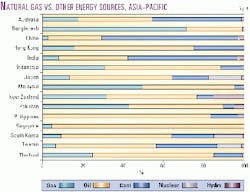

Fig. 2 shows the relative growth of gas consumption for 1989-99. Although China's natural gas consumption has increased consistently, the consumption growth of natural gas in the Asia-Pacific region would have been higher (in percentage terms) without China.

Natural gas consumption actually increased during the economic crisis, registering the highest growth rate, compared with oil and coal, during 1989-99. Indeed, the Asia-Pacific region represents one of the fastest-growing areas for the global natural gas industry.

In 1989-99, gas consumption in Asia-Pacific grew at an average rate of almost 7%/year compared with a world average of less than 2%/year. Based on this premise, gas will likely be the preferred fuel over other primary energy sources-whenever economics warrant it-and therefore is generally projected to have higher consumption growth over other fuels.

Because natural gas is a cleaner fuel, increasing its role in the primary energy mix also reduces emission levels, benefiting countries with environmental constraints. The growth potential of Asian developing countries is enormous, as their primary energy demand, per capita, is still very low (Fig. 3).

Therefore, the rebound in economic growth after the fiscal crisis in the East Asian countries will continue to translate into renewed and healthy energy demand growth rates for the region.

As countries advance economically, the ability to afford the initial capital investments for infrastructure increases. This also is the case in the utilization of natural gas where major constraints are caused by a lack of infrastructure.

It can then be assumed that the role of natural gas in the primary energy mix in Asian developing countries will increase as infrastructure develops. This is especially true in countries where gas utilization is low or nonexistent.

Gas supply, deregulation

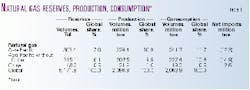

Fig. 4 shows the role of natural gas in the primary energy mix of Asia-Pacific countries. In terms of natural gas resources, these countries can be classified as:

- Countries with significant reserves relative to domestic consumption; they can export gas.

- Countries with substantial reserves used primarily for domestic consumption.

- Countries with limited or no gas reserves.

In terms of gas reserves, however, even Indonesia, the area's largest producer and exporter, or Malaysia, which has the largest reserves in the region, pales in comparison with "world-scale" reserves owners such as Qatar-a country with a population of fewer than 1 million-which has gas reserves that surpass 80% of all of the Asia-Pacific countries combined.

Although the reserve-to-production ratios of the Asia-Pacific's major producers are currently 30 years or more, rapid consumption growth in the region will eventually require imports from other regions.

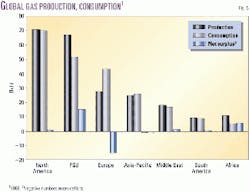

Unlike the case of oil, the present imbalance in gas production and consumption in the Asia-Pacific region is not severe. In 1999, less than 5% of total gas consumption originated from imports, compared to about 60% for oil. Fig. 5 shows natural gas production and consumption in the Asia-Pacific region in the global context. Natural gas imports have come from the Middle East and, to a much lesser extent, the US (Alaska).

Due to the geography of the region and the location of the major gas im porters and suppliers, most of the international trade of gas in the Asia-Pacific region is in the form of LNG. Short distance pipelines, however, may well be the most economical supply method.

The existence of substantial base demand in some countries and the continuing gas finds near demand centers will certainly increase utilization. Trades between neighboring countries will continue to increase whenever untapped supplies can be economically utilized.

Complications in natural gas supply arise when there are several projects competing to fulfill the (potential) energy demand. While competition from different sources of natural gas, including LNG, does not necessarily affect the eventual gas consumption, a type of supply other than natural gas coming in will affect the feasibility of the natural gas supply. This will result in delaying a few gas projects.

Moreover, a commitment to take substantial amounts of gas over a long period-necessary to make a project economically feasible-jeopardizes the buyers' flexibility. This is especially true if less-expensive new sources of natural gas arise; it is the inherent problem with LNG trades.

The anticipated high consumption growth depends largely on how buyers, sellers, and financiers of each project arrive at flexible terms, both in the period of the contract and the minimum gas take.

In an era of deregulation and the increasing role of independent power, the traditional contract structure for LNG seems inappropriate. It commits the buyer to 20-25-year contracts and 90-95% offtake before take-or-pay clauses are triggered.

The inflexibility of the contract structure is itself an impediment to expanding gas use, as the buyer, typically a power company, justifiably fears facing the harsh take-or-pay situation. Inability to take the gas can result from an economic downturn or loss of markets to independent power producers (IPPs).

IPPs themselves fear the same inflexibility. As such, consumption may well be below potential demand because of the nature of the contracts. This is not a serious problem in the US or Europe, where multiple pipelines and multiple buyers can buy gas at short notice or even in futures exchanges.

In Asia, however, the long distance between buyers and sellers, the peaking problems for gas demand, and the lack of a gas consumption culture have added to the inflexibility and have impeded gas use in certain markets.

Emerging is a widespread realization that the system must change. Take-or-pay contracts do not protect sellers and can reduce potential gas demand. The need for flexibility is obvious, and both sellers and financiers seem ready to look at new options. It will take 5 years or more for the system to change fundamentally, but a new gas world is unfolding.

Asian LNG demand

Total Asian-Pacific LNG demand is expected to grow by 16 million tonnes per year (tpy) in 2000-05 and by 30 million tpy during 2005-10.

The greatest growth will be in India and South Korea. Japan will see little growth through 2010. South Korea will have average annual growth rates (AAGR) of 4.5% and 7.1% in 2000-05 and in 2005-10 respectively.

Taiwan will have an AAGR of 10.2% in 2000-05 and 9.1% during 2005-10.

During 2005-10, China's AAGR for LNG demand will be 13.6%, and India's AAGR for LNG demand will be 19.1%.

The overall AAGR for Asia-Pacific LNG demand will be 4.2% during 2000-05 and 6.3% in 2005-10. Table 2 shows the Asia-Pacific LNG demand forecast through 2010.

India

In India, companies are racing to finance and build LNG import terminals, followed by a power plant, and eventually a grid of pipelines to reach consumers. In spite of numerous projects, there is only room for 4-5 terminals.

Many of the proposed LNG terminal projects would serve the same market: Dahej, Hazira, Jamnagar and Pipavav in Gujarat; Dabhol and Trombay in Maharashtra; Mangalore in Karnataka; Cochin in Kerala; Ennore in Tamil Nadu; and the Kakinada projects in Andhra Pradesh.

With such intense competition, LNG prices into India are likely to be very reasonable. Dahej already has supply arrangements and excellent government relations. Realistically only two or three other players will enter the market.

India's gas regulations also are changing. While there is a current import tax of 28% on LNG, a national gas act is being formulated to reduce the import tax to levels more in line with those of other LNG importers. South Korea charges a 5% customs duty; Europe, Japan, and the US have no tax whatsoever. The gas act will likely make gas development more transparent, consistent, and less ambiguous for foreign companies and financiers.

South Korea

South Korea, the second largest LNG importer in the world, contains the fastest-growing LNG market in the Asia-Pacific region. Since 1987, gas consumption has increased 18.7%/year due to a number of factors:

- Economic growth.

- Increased energy requirements in city gas and power generation.

- Government efforts to promote oil and coal alternatives.

- More-stringent environmental regulations that favor cleaner fuels such as natural gas and nuclear power, although the populations of both South Korea and Japan fear nuclear power, especially after Japan's recent nuclear accident near residential areas.

LNG demand growth in South Korea during 1991-99 was 5.78 and 1.35 times higher than Japanese and Taiwanese markets. Although South Korea is not bound by the Kyoto Protocol, the government has volunteered to reduce greenhouse emissions starting in 2018.

South Korea relies on imported LNG to meet all of its natural gas requirements. This trend will continue despite recent gas discoveries, which are not expected to provide significant shares to total supply.

If the 2002 volume of imported LNG (16.9 million tpy) continues until 2020, small gaps in 2005 and 2010 can be filled by flexibility in existing contracts or spot cargo sales.

Korea Gas Corp. or its successors would need to negotiate for additional supplies. LNG options are likely candidates, either from increased imports under existing contracts or new contracts with projects such as the Northwest Shelf's Train 5, Tangguh, or Yemen.

Japan

Japan is the world's largest LNG consumer, with 51.3 million tpy in 1999. Gas demand weakened in the 1990s, however, due to the worst economic recession in the post-war period. Although signs of recovery are emerging, the future Japanese economy and gas outlooks are still guarded.

Growth rate in gas demand will reach only 1.6% during 1999-2010, the lowest among LNG importing countries in Asia and well below the projected regional LNG demand average of 5.3%.

Although Japan is the seventh biggest natural gas consumer in the world, it has a very limited gas transmission system, thus lacking the requisite gas infrastructure to facilitate growth in gas demand. The underdeveloped gas distribution system explains why Japanese consumers pay energy retail prices several times higher than Americans or Europeans.

Delivering gas to many additional small gas users could have a profound impact on domestic gas consumption, but mountainous inland terrain and right-of-way issues block development of a gas transmission network. In response to the lack of a national trunkline, the Japanese have seriously considered expanding the country's existing gas pipeline system.

Private funding may be necessary, given the current state of the economy and the stringent numerous requirements that accompany a public undertaking. Japan will have to make a firm decision around 2010-11 regarding the pipeline construction, either from Sakhalin or Yakutia, to fill the anticipated deficit of 12 million tpy in 2020.

A combination of factors, such as the slow recovery of the domestic economy, the partial deregulation of the gas and electricity markets, and the inadequate provisions of the gas infrastructure all contribute to the prevailing uncertainty over the future of Japan's gas demand.

With limited proven natural gas reserves, Japan will continue to rely heavily on imported natural gas, primarily LNG; to meet its huge domestic gas demand, especially if the government decides to enforce the Kyoto Protocol.

Taiwan

Taiwan's state-owned Chinese Petroleum Corp. (CPC) has been the country's sole natural gas supplier, importing LNG because of diminishing domestic natural gas production. CPC has three long-term contracts that can be expanded-one with Malaysia and two with Indonesia. Australia may be a likely future source of LNG supply to Taiwan.

Taiwan will continue to rely on im ported LNG because of its rising demand for natural gas and its declining domestic production. LNG consumption will in crease to about 7.0 million tpy in 2005 and 10.8 million tpy in 2010.

A newly passed government procurement law has ended CPC's monopoly over LNG purchasing, however, and Taipower's (Taiwan Power Co.) gas-fired plants must now obtain fuel through open tender. CPC will be competing with other Taiwanese companies for LNG imports, especially after the existing receiving terminal in southern Taiwan expands to 11.4 million tonnes in 2002-06 and a proposed privately owned second terminal is built in northern Taiwan.

More gas-fired plants will be needed in 2005 than Taipower currently has planned. Industrial use growth will be moderate, but town gas consumption will grow faster.

China

China is one of many Asian countries that currently engage in no international gas trade, except for its gas exports to Hong Kong, now part of China.

Natural gas currently plays only a minor role in China's overall energy mix, but the situation is changing. Since the late 1990s, the Chinese government started improving infrastructure and is now considering LNG imports.

Compared with oil and coal, natural gas promises to have a bright future in China. China is expected to start importing LNG by 2006 (base case), compared with partial imports of Sakhalin gas to northeastern China in 2010 and Russian Irkutsk imports from 2015.

Contract changes needed

There is sufficient LNG supply in Asia-Pacific and from the outside, but increased gas use can only occur through fundamental changes in the current structure of gas contracts. The changes must include shorter-length contracts and latitude in the take-or-pay clause to make gas use more attractive to end-users compared with coal and oil use.

Supply side factors, such as infrastructure developments, construction of cross-border pipelines, enforcement of the Kyoto Protocol emission requirements, delays in nuclear development, and gas and power sector deregulation are reasonable concerns for both government and private companies.

It is even more important to increase demand, however. Restructuring LNG contracts is currently the most important step in that direction. Shorter contracts that operate more like short-term coal or oil contracts will be better able to accommodate demand fluctuations, thus encouraging growth in LNG use.

More importantly, the issue involving the take-or-pay clause, which has been the greatest single barrier to increased gas consumption, needs resolution. One solution is to use an insurance or financial buffering mechanism to protect buyers against the full force of take-or-pay obligations. That solution, however, must not prevent new LNG projects from obtaining financing.

LNG suppliers may provide the solution. Efforts to boost competitiveness have led Indonesia's state-owned oil and gas company Pertamina to contemplate offering 5-10-year short-term LNG contracts to established markets in Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan.

The LNG business has evolved into a buyer's market. Sellers must adjust to this reality to remain competitive, especially with competition from Australia, Malaysia, and Qatar.

LNG's future east of Suez

With many long-term contracts expiring during the next decade and new buyers entering the LNG market, contract volumes will necessarily change. Renewals will be for shorter terms and there will be much more lifting flexibility. This will create a sustainable environment for the evolving LNG spot market.

All of these changes are already taking place, and the east-of-Suez market is leading the way.

The expansion possibilities at existing sites preclude a real need for grassroots LNG facilities until 2010-15. South Korea and India, the most important new buyer of LNG, will dominate the LNG market. China will be slow to enter the market, and Taiwan will see modest increases of another train or two.

Spot purchases of LNG will rise substantially, but the oil price linkage will continue for many more years. A spot market for gas will slowly emerge by 2007-10 as many contracts come up for renewal.

The critical supply-side questions regarding infrastructure and supply sourcing will resolve themselves quickly after the demand side is freed of its high risks.

The authors

Fereidun Fesharaki is president and founder of Fesharaki Associates Consulting & Technical Services (FACTS Inc.). He also is a senior fellow at the East-West Center, Honolulu. Fesharaki received his PhD in economics from the University of Surrey, England. He then completed a visiting fellowship at Harvard University's Center for Middle Eastern Studies. In the late 1970s, he attended the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries' ministerial conferences as energy adviser to the prime minister of Iran.

Robert R. Smith is a senior associate at FACTS Inc. and a researcher at the East-West Center in Honolulu. His research focus is on downstream oil and natural gas markets and energy policy issues east of the Suez Canal. He holds an MA in Asian studies from the University of Hawaii and a BA from Johns Hopkins University.

This data, since updated, was presented to LNG 13 Conference, Seoul, South Korea, May 14-17, 2001.