OPEC'S EVOLVING ROLE: Analysts discuss OPEC's role in next potential oil price shock

The world is grappling with yet another spike in oil prices, in some respects like those of the past 3 decades.

This latest spike in prices has its roots in, among other factors, the oil price collapse of 1998-99 that spawned a massive retrenchment in upstream capital investment. That collapse in exploration and production spending, in turn, has left the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries holding the whip hand over oil markets with a relatively small increment of spare productive capacity, which the group has used mainly to bolster oil prices.

But there remains a lingering concern that higher prices will again boost non-OPEC production, thus eating away at OPEC's market share.

So it will largely be actions taken by OPEC in the months to come, working in concert with other market forces, that will play a vital role in preventing another oil price collapse, such as the one in 1986 that had its roots in the oil price shock of 1979-81.

Events over the coming months will reveal just how much OPEC has learned about effectively managing its oil supply. So far this year, its efforts to sustain an oil price that falls within its established $22-28/bbl band for the OPEC marker basket of crudes have been successful (OGJ, June 11, 2001, Newsletter, p. 5).

Yet, even if the organization has gained newfound insight into any of its previous miscalculations, will those OPEC member nations prone to production quota-cheating, in combination with recurring uncertainty over the status of Iraq's oil exports, thwart the group's efforts to continue to do so?

OGJ interviewed a number of top analysts to gain perspective on whether OPEC has learned from its mistakes of the past or is condemned to repeat them.

Learning from the past

Looking back at the organization's previous actions during past times of crisis may be one of the best ways to gauge its future actions-and its motives behind those actions (Table 1).

For example, certain parallels exist between OPEC's actions during 1979-81 and those undertaken today, according to Michael C. Lynch, chief energy economist with Lexington, Mass.-based DRI-WEFA.

Currently, he said, OPEC is taking the short-term oil price spike and attempting to make it a plateau. "The difference [now] is that the price spike is much lower-and the plateau they are trying to construct is more sustainable-than the one in 1979-81, when prices were about $50/bbl, in 2000 dollars.

"After 1986, many in OPEC admitted that they had miscalculated and kept prices too high for too long-with the advice of some of the finest petroleum experts in the world-arguing that they would not do so again," he added.

However, many of those OPEC ministers are no longer with the organization, Lynch explained, leaving the decision-making up to members who may not be as knowledgeable about the movement of oil markets.

"As evidence of this," Lynch noted, "the talk of a 'fair' price for oil has resurfaced among many in OPEC, along with the comparison of oil prices to that for other liquids," such as mineral water and perfume.

"OPEC learned the hard way in 1986 that consumers are not a body of industrialized nations making political choices about fuel use, but rather billions of hard-eyed individuals who look at comparative costs," he observed.

"And oil companies will not refrain from lucrative upstream investments out of a concern for the well-being of OPEC nations," he continued. "The possibility that the current round of officials in OPEC nations will relearn that lesson the hard way should give the industry pause," Lynch commented.

Sarah Emerson, managing director with Energy Security Analysis Inc., Wakefield, Mass., believes Lynch's comments to be on target, adding that there is another major difference between the present crisis and the second oil shock that occurred in 1979-81: the increasing isolation of the US petroleum product markets. To some degree, this is true of Europe's markets as well, Emerson said.

"We now make high-tech, clean fuels," Emerson explained, which will become even cleaner as the US and Europe remove increasingly more sulfur from those fuels. "We do this with a shortage of refining capacity," she added.

"This means that refining margins are strong and will re main strong-especially in the US-for a couple more years as we hit the apex of the boom," Emerson forecasted.

Because of this, she explained, OPEC will not be able to manage the market with its OPEC basket price band-due to the fact that the organization does not take into account the premium of either West Texas Intermediate or US petroleum product prices.

"So, periodically, product prices in the world's largest economy will be much higher than the OPEC basket benchmark," Emerson said. The distance between the basket price and US wholesale product prices will cause problems for OPEC, she explained, because it weakens the impact of the organization's production decisions on the average US consumer. "The result will be fewer sports utility vehicles (SUVs), higher miles per gallon, and more interest in hybrid vehicles," she said.

"Worrying about keeping prices in the $22-$28/bbl band for the OPEC basket is a little like rearranging the deck chairs [on the Titanic] with the iceberg in sight. OPEC can try to sit back and say the US problem is a refining problem and not theirs, but the potential demand response will ultimately be OPEC's problem," Emerson stated.

Amy Jaffe, senior energy advisor at Rice University's James A. Baker III Institute for Public Policy, said that the situation today is quite different from that in 1979-81.

"The closest parallel," Jaffe observed, "was that in 1979, the revolution in Iran made it very difficult to project how long there might be a disruption in oil flow from the Persian Gulf. Today, with the politics of the sanctions on Iraq, we have the same questions about the uncertainty surrounding exports from Iraq."

But, in some ways, she explained, the US is better prepared today to deal with an Iraqi supply disruption, because there is a precedent in 1990 for OPEC countries to make up for the lost volume.

"Also, we have the [International Energy Agency] stocks system," she added. "Still, spare capacity in OPEC is much smaller today than it was in the 1970s, and that will pose a challenge if a cut-off from Iraq is prolonged." The institute estimates today's spare OPEC capacity to be less than 2 million b/d, while in 1973, it was 3.5 million b/d. In 1990, meanwhile-prior to Iraq's invasion to Kuwait-it was over 5 million b/d, Jaffe noted.

OPEC's strategy

Despite what OPEC may have learned from years past, the longer oil prices stay high, the greater the long-term effects on demand will become, the analysts agreed.

"I think that OPEC is trying to maximize its short-term revenue, because the various members are almost uniformly in dire financial straits," Lynch observed. "They can easily afford the cost of new production capacity, if they choose to allocate the money from the budgets."

Lynch noted that sustained high oil prices are, in fact, having some effect on demand, adding that US consumers appear to be "cooling their torrid love affair" with SUVs. "Energy efficiency more generally is becoming a priority," he said.

Compared with 1979-81, however, the effect that sustained high oil prices have on demand should be smaller, Lynch suspected. Essentially, this is due to three facts:

- In the late 1970s and early 1980s, natural gas infrastructure was just starting to be built in Europe.

- Efforts to switch to coal in many places had been initiated since 1973-74.

- Third world countries-which tend to be more income-responsive than price-responsive-have become a much larger part of the global oil demand equation.

"On the supply side," Lynch said, "OPEC has opened a Pandora's box." Over the next 3-5 years, Lynch expects OPEC will continue to lose some market share from other developed energy sources, such as Canadian oil sands development, gas-to-liquids projects, and deepwater and Caspian Sea oil projects.

"The pressure won't be as bad as the cartel experienced in the early 1980s, but pressure there will be," Lynch said.

Jaffe also sees OPEC benefiting monetarily in the short term: "OPEC countries such as Venezuela, Nigeria, and Saudi Arabia have been slow to make investments in future oil production capacity, feeling it is better to take the short-term gain of higher prices," she said. "OPEC's strategy is to try to fill government coffers to stave off political problems at home and social unrest and to gain its 'fair share' of the rents from its resources."

Current high prices, however, will hurt demand over time, Jaffe agreed, as can be seen by the build-up of competing supplies, including the continuing workover projects in Russia as well as the continuing interest to invest in development projects in Brazil and Angola.

Also, Jaffe explained, "Investors are talking more about clean coal, nuclear energy, and hybrid cars as a result of higher oil prices. In addition to prices, environmental pressures are promoting alternative technologies. The elasticity of oil demand is low in the short term, but the longer prices remain high, the more response there will be towards promoting competing supplies, alternative fuels, conservation, greater energy efficiency, and falling demand.

"Markets will eventually correct, as they did in the 1980s. If prices remain high, structural changes are likely to take place that will have long-term impact."

Spare capacity

For much of the 1980s, Lynch said, OPEC's spare capacity was estimated at more than 10 million b/d. As of late, however, he noted, "OPEC has just been through a lengthy period when they did not have to struggle with the burden of spare capacityellipseincluding a couple of years-1996 and 2000-when they were essentially producing at full capacity."

Some member countries, such as Algeria, Nigeria, and Venezuela, have already been pushing to increase upstream investment-both their own state companies' and foreign companies'-to add to their oil revenue, Lynch said. The recent market tightness has encouraged the belief that there is room for their new capacity, he explained.

"However, as they have done before, they are riding the wrong side of the wave," Lynch observed. "Most of the capacity will come on line in 2002-04, when the market is likely to be weaker than now, and the cartel will thus have a greater struggle to maintain discipline.

"Discipline is easy to maintain when you have no opportunity to break it. By adding capacity, OPEC is like a dieter buying a cake but arguing that it will demonstrate will power."

Jaffe concurred, saying, "There is a possible scenario where OPEC will find itself under pressure in the coming years. If the world economy slips into recession, and non-OPEC production rises as new drilling in 2000 and 2001 starts to pay off, OPEC may find itself having to cut back production significantly to defend prices.

"This happened in the early 1980s and could easily happen again around 2003. It will be especially the case if OPEC countries expand capacity as is planned in key countries such as Kuwait and Iran.

"If the situation in Iraq changes, and investment in oil fields there can take place, then the possibility of OPEC surpluses becomes more likely. Once one major OPEC producer begins a major capacity push-whether it's Iraq, Venezuela, Saudi Arabia, or Kuwait-other OPEC countries will be forced to follow suit. We saw this in the late 1980s, and this pattern could easily reemerge as more and more foreign investment goes into these countries over time."

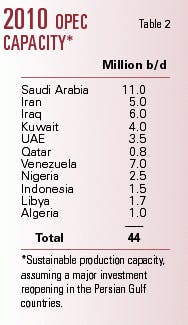

Looking at the mid- to long-term scenario, Jaffe speculated that if Saudi Arabia and Kuwait were to be opened up for foreign investment and investment in Iraq could be possible, OPEC sustainable capacity might rise to as high as 44 million b/d by 2010 from its current capacity of about 30 million b/d (Table 2).

Distinct differences

In comparing events and OPEC reactions during 1979-81 with what is going on today, there are several notable differences, Lynch explained.

"Energy markets are much more efficient and transparent [now] than in 1979-81-though hardly completely efficient and transparent. This makes it easier for the market to respond to price signalsellipseand thus move back to equilibrium faster.

"Also, the deregulation of other markets helps, including US natural gas markets which-long term-should be able to provide at least some short-term relief when oil markets tighten (and vice-versa, as we have seen this year).

"In addition, the [US] Strategic Petroleum Reserve deters political threats from oil but doesn't prevent all supply disruptions, as Iraq has demonstrated. Thus, the threat of an embargo is much less.

"All in all, there is much greater likelihood that markets will be revert to the mean much faster."

Lynch forecasts that, although the oil market will face a number of factors that will make it more volatile, the market itself has become more adept at responding to and offsetting such volatility.

The lower degree of surplus capacity held by OPEC is one such factor. "Because the 2000-01 price spike is much less than the 1979-81 spike," Lynch said, "the demand side effects are lower, and OPEC is unlikely to have the enormous amount of surplus capacity that it did in the mid-1980s (about 15 million b/d at one point). And the elements that led the refining sector to be so overbuilt are also unlikely to reoccur, so that sector shouldn't become depressed again for a lengthy period."

Likely scenarios

In Lynch's view, three primary scenarios are likely: soft landing, hard landing, and delayed crash.

- Soft landing. OPEC handles things right, causing the oil price to decline just enough to discourage significant investment in some of the major threats to the organization's market share-namely GTL technology-while causing a delay in, or reduction of, investment in other developments, such as oil sands. The result would be a price range of $22-26/bbl for WTI, or a bit higher.

- Hard landing. OPEC handles things badly and suddenly is faced with a period where there is a lot of cheating on production quotas just as markets are weakening, thus collapsing the oil price to somewhere around $18-22/bbl for WTI. This will last awhile, before it gets dragged back up to $22-24/bbl.

- Delayed crash. OPEC keeps oil prices high too long, thus further shrinking the group's market share. In addition, because there is a lot of capacity installed that will keep producing no matter what happens, the price crash will likely be longer-lasting, but probably not too much lower than the hard-landing scenario.

"It's important that certain elements are true to all scenarios," Lynch added. "I don't see price volatility moderating any time soon. Also, refining margins will fluctuate but should be better than they were through the 1990s," he said.

"The biggest question is whether or not decision-makers in OPEC, consumer country governments, and the oil industry have learned the lessons of the 1970s. The fear is that too many in OPEC will become enamored of high prices and think that what is sustainable for 12 months can be sustained for 12 years.

"Also, too many in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development countries think that the government can manage the market better than the market, and too many in industry convince themselves that this time, high prices really will stay up, that this is not a cycle, that they should hire everyone they can and sign long-term contracts for equipment at whatever rates are offered."