Africa in Perspective: Natural gas offers Nigeria huge potential, challenge

The Nigerian gas industry offers huge challenges and potential.

With a reserve base of 130 tcf and a 2.6% share of world reserves, Nigeria ranks tenth among gas-bearing nations. The country's gas reserves-to-production ratio is estimated to be about 120 years. Oil's ratio is only 35 years, so Nigeria is increasingly considered a gas province.

Reserves are split nearly evenly between associated and nonassociated gas. However, exploitation so far has been concentrated on associated gas, which accounts for 70% of total gas production. Only 35% of the associated gas produced is gainfully used. The other 65% is flared in the oil fields.

With increasing focus on sustainable development worldwide, current Nigerian government policy requires all flares eliminated by 2008. This is expected to decisively address the colossal waste in such a valuable resource and the attendant devastating effect on the environment. Meanwhile, the policy provides a driving force for rapid investment and development in the industry. Consequently, several key gas utilization projects have either been recently completed or are at various stages of implementation. These include petrochemicals processing, liquefied natural gas, natural gas liquids extraction, aluminum smelting, and gas-to-liquids processing.

Stratifying the gas sector into upstream, midstream, and downstream segments, most of these projects are evidently in the midstream segment, which is essentially focused on gas processing and is basically driven by process engineering. Chemical engineers are therefore increasingly playing key roles in the gas sector.

In addition to the ongoing projects there is evidently tremendous scope for new investments and projects in all aspects of gas development. A number of constraints are identified that could impair these developments. These are lack of gas transmission infrastructure, grossly underutilized gas supply facilities associated with public utilities and industries, restiveness among the host communities in the oil fields, absence of a well-articulated gas development policy, and inadequate training facilities for chemical engineering students. Measures needed to overcome these constraints are highlighted here.

Nigeria today

Nigeria, on Africa's west coast, has geography dominated by the Niger River and its delta, one of the world's largest wetlands.

Ruled by a military regime for nearly 30 years, Nigeria since mid-1999 is led by a democratic regime.

With a population estimated at 110 million, Nigeria is Africa's largest country. The official language is English, but more than 250 ethnic groups also speak various local languages.

Oil and gas dominate Nigeria's economy, and more than 65% of government revenue and nearly 95% of foreign exchange earnings depend on hydrocarbons. The petroleum sector contributes 25-30% of gross domestic product.1

Shell mostly pioneered oil and gas exploration. The company started oil production and export in 1958. Nigeria produces 2 million b/d of crude oil from a proved reserve base of about 25 billion bbl. All production is from the Niger Delta basin in a variety of land, swamp, and shallow offshore concessions. Lately exploration and exploitation of the deep offshore has also started to arouse excitement, and this area appears to hold keen prospects.2

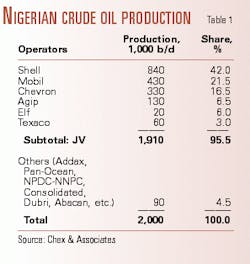

More than 95% of the oil production is in the hands of major international corporations in joint venture with government-owned Nigerian National Petroleum Corp. The rest is shared by various independents. Some new concessions are in the form of production-sharing contracts with NNPC (Table 1).

Resource, challenges

Gas production in Nigeria is only about 3 bcfd, and there is as yet only limited effort at deliberate exploration specifically for gas. Despite its high gas resource ranking, Nigeria does not number among the top 20 gas producing or utilizing nations.3 This spells a huge potential in gas development there.

About 50% of proved gas reserves are associated gas, while the rest is nonassociated gas.4 Associated gas production is more than 2 bcfd, but about 1.4 bcfd is flared.

The continued flaring of gas is attributable to the economy's inadequate consumption capacity for gas as manifest in the high capital cost of associated gas gathering and limited domestic demand. The implications of this situation are huge waste of otherwise valuable natural resource and negative impact on the environment in the form of undesirable heat and light effects. Clearly on both scores the practice is considered most objectionable.

The government approach to resolving this problem over the years has been to impose progressively stiffer penalties on producers for every unit volume of gas flared. The result was a modest 4-5% growth in gas utilization, which barely affected the problem.5 Consequently, the government has lately set the date for flaring to end.

These conditions give way to enormous challenges:

- Race to comply with government "flare-down" policy.

- Compeling need to curtail flaring.

- Increasing realization of flaring's environmental effects.

- Price advantage relative to competing fuels.

- Relative cleanliness of combustion.

- Improved fiscal package for investment in form of incentives-relief, duty and royalty concessions, enhanced capital allowances, etc.

Gas utilization projects

The result of this impetus is the initiation of various major gas utilization projects the past few years, some of which are already completed and operational (Fig.1 and Table 2).

Gathering, conditioning

This in fact represents the primary processing stage for produced natural gas prior to any further downstream utilization. Virtually all of the major producers have installations for gathering and conditioning their produced gas.

To a measurable extent, development and investment in this area lately are driven by the demands of the growing LNG operations. Shell in particular, which supplies 60% of the feedstock requirements for LNG, has been active in this regard. Shell is completing construction of five associated gas gathering projects, Soku, Belema, Odidi, Obigbo, and Forcados-Yokri, with combined capacity of about 700 MMcfd and an investment of nearly $2 billion. Others such as Agip SpA and TotalFinaElf have recently completed similar projects.

Shell in a more recent initiative has planned an offshore gas gathering system to harness offshore gas from the western Niger Delta to feed the LNG plant.6

Gas lift-reinjection

Gas lift and reinjection represent the oldest associated gas applications in Nigeria. Even at that, new installations are continuously being built as more fields lose natural drive. All the major producers operate such installations.

Power generation

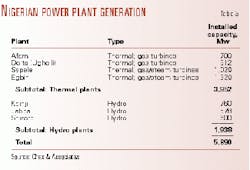

This is also one of the oldest gas applications. Virtually all electricity generation in Nigeria is from either gas or hydropower, with the gas-fired power plants accounting for 3,875 Mw or 67% of installed capacity (Table 3).

Interest has surged in gas-fired independent power plants recently. These plants will go a long way to stabilize the power sector and stimulate gas consumption. They are expected to operate more efficiently than existing public power plants.

Industrial fuel

Natural gas finds limited use as an industrial fuel in the Port Harcourt-Aba and Warri-Ughelli industrial areas adjoining the eastern and western oil producing areas, respectively. Among these are two major steel mills.

Gas is also used as an industrial fuel to power equipment in the oil fields. Lately two major projects have been put in place by NNPC affiliate Nigerian Gas Co. for major supplies to the Greater Lagos Industrial Area (Escravos-Lagos Pipeline, ELP) and to a new aluminum smelter complex at Ikot Abasi, 150 km east of Port Harcourt (Alscon line).

Evidently development in this sector has been severely restricted by inadequate distribution infrastructure. A key development therefore has been the entry of new players bringing in investment in distribution. Prominent among these are a subsidiary of Shell and a local group in association with Asian interests, both of which are involved in distribution and sales to consumers in the Greater Lagos Industrial Area.

Domestic fuel

Nigeria has almost no commercial application of gas as a domestic fuel.

This is due to lack of distribution infrastructure.

Export gas

Plans are advanced with respect to the West African Gas Pipeline, envisaged to export gas from Nigerian oil fields to Benin, Togo, and Ghana.

WAGP is sponsored by Chevron and Shell and national oil and gas companies of the four countries.

The planned 750 km pipeline is to begin exports at 50 MMcfd in 2003 and peak at 100 MMcfd around 2010.

LNG

Nigerian LNG, a group involving Shell, Elf, Agip, and NNPC, completed the Bonny LNG project and exported the first cargo to southern Europe in October 1999 after many years of delay.

The $3.7 billion, two-train base project has an output capacity of 5.8 million tonnes/year plus 6,700 b/d of recovered condensate. Natural gas feedstock is about 900 MMcfd.

The engineering, procurement, and construction contract for the third train awarded in February 1999 is to increase output 50% and generate capacity for a further 1 million tonnes/year of LPG.

Completion of Train 3 by 2002 will boost the flare-down effort as the extra feedstock will be almost entirely associated gas.7

The proposals look so bright on both the marketing and supply sides that negotiations have begun for Trains 4 and 5, which on realization will represent the limiting capacity that can be accommodated on site. The main marketing thrust in this regard is the emergent gas market in South America, especially Brazil.

Fractionation-NGL export

Chevron, Agip, and Mobil have completed and commissioned three major gas fractionation plants in the last 5 years (Table 4).

Chevron has almost completed an expansion of its base project, which when commissioned about mid-2001 will boost output 70%. These projects, in conjunction with the LNG project, will inject diversity into Nigeria's foreign exchange earnings profile.

Other smaller projects have been proposed by local independent groups in association with various US interests. Exciting potential evidently exists in this area, especially if the technology for skid-mounted minifractionation plants can be competitively deployed to recover NGL from gas flare streams at the numerous flow stations dotted across the oil fields.

Petrochemical feed

Two relatively new petrochemical complexes around Port Harcourt in the eastern Niger Delta produce plastic polymers and nitrogen fertilizers from gas feedstocks supplied by Agip and Shell. State-dominated companies own and operate both plants.

Gas deliveries to both plants are at a dismal 20% of installed capacity due to poor plant performance. This notwithstanding, the option of converting gas to petrochemicals holds high potential and arouses keen interest. A few major private-sector initiatives for such purposes as methanol and methyl tertiary butyl ether are in the works. It is also expected that the option of skid-mounted minifertilizer plants will be increasingly attractive.

Gas-to-liquids

Chevron has proposed a GTL project based on the Sasol process. This would obviously represent a major challenge as GTL technology is relatively new.

Compressed natural gas

CNG is spearheading a project for direct use of gas as an automotive fuel. This is expected to be a relatively cheaper and environmentally friendly fuel option. However, the technology is still fairly new, and most vehicles are not designed for this. Besides, refueling infrastructure is not available and will require considerable investment.

Gas consumption pattern

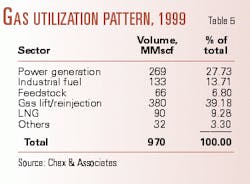

Before LNG plant commissioning, power generation and reinjection were the dominant gas consumers. Figures for 1999 indicate shares of 28% and 30%, respectively, for these streams. The LNG plant consumed nearly 10% (Table 5).

Details of consumption in 2000 are not yet available; however, gas demand for liquefaction is expected to become dominant, with a share of 40-50%, as LNG operations stabilize. Consequently, total demand is also expected to rise steeply to more than 1.6 bcfd.

Growth constraints

A number of factors can be readily identified as working against gas segment growth.

Inadequate infrastructure in the form of limited trunklines and industrial distribution lines as well as the absence of domestic supply infrastructure continues to be a major limitation.5

Most gas-dependent industries are public enterprises with poor track records. They are afflicted by a common problem of grossly underperforming gas supply assets.9 Utilization of such assets ranges from 0.2% for the supplies to the virtually abandoned steel mills to 19% for supplies to the power plants.

Oil producing communities have become increasingly restless the past few years. This is in response to years of neglect, alienation from the developmental process, and environmental devastation. This sometimes degenerates into militancy and outright hostility to oil and gas facilities.

The government has set up the Nigeria Delta Development Commission, designed to be a key intervention instrument for channeling resources back to the area. It is perhaps a local version of the famous Marshal Plan.

Informed opinion in Nigeria's energy sector believes that an energy policy that will set guidelines for rational, safe, and sustainable exploitation is long over due. It should be expected that a gas policy will derive from this.

In the absence of such well-articulated guidelines, development will tend to be haphazard and full potentials will hardly ever be achieved.

Outlook

Against the foregoing background, tremendous potential exists for investment and growth in Nigeria's gas sector.

The huge public investments in power generation, steel mills, aluminum smelters, and petrochemical plants must be deregulated or privatized in order to inject badly needed commercial discipline and investment. For this to occur, the government must complete its privatization efforts and reputable international companies must take up the offers.

A bold initiative is required in respect to trunkline transmission facilities and to stimulate domestic and industrial demand. Preferably, NGC should be restructured as a consortium company in which the major gas producers and NNPC are joint stockholders.

References

- Shote, K., "World Oil and Gas Sourcebook," 1998.

- Nwawka, E.N., "Long term viability of Nigeria's oil and gas business for sustainable national growth," SPE annual international conference, Abuja, Nigeria, August 1999.

- Caldwell, P.L., "Natural gas projects: Prospects, financing & incentives on reducing/eliminating gas flaring," Nigerian Gas Association workshop, Abuja, November 1999.

- Galus-Obaseki, J., "Natural gas: Creating additional wealth for the future development of Nigeria," Nigerian Gas Association workshop, Abuja, November 1999.

- Ofurhie, M.A., "Managing the natural gas industry in the next millennium," proceedings Nigerian Society of Chemical Engineers, Port Harcourt, November 1999.

- Nwasike, O.T., Okwuokenye, C.N., and Nwagu, N.H., "Process technologies and considerations for gathering associated gas: Experiences from the Niger Delta, West Africa," Offshore Technology Conference, Houston, May 2000.

- Jamieson, A., "LNG"s contribution to the creation of wealth in Nigeria," Nigerian Gas Association workshop, Abuja, November 1999.

- Erinne, N.J., "Imperatives of process engineering in the midstream petroleum industry," proceedings Nigeria Society of Chemical Engineers, Port Harcourt, November 1999.

- Inyang, S., "Natural gas, the energy for the next millennium," proceedings Nigeria Society of Chemical Engineers, Port Harcourt, November 1999.

The author

N. John Erinne is employed with Chex & Associates, Lagos. E-mail: [email protected]

Adapted from a paper prepared for presentation at the AIChE spring national meeting, Houston, Apr. 22-26, 2001.