Caspian Energy Exports New Caspian players face challenges; rewards if well-informed

With the race to export potentially vast volumes of oil and natural gas from the Caspian Sea nations in full swing, is the time ripe for new investors to look towards opportunities in this region? It may well be.

However, any company planning to start up or increase business in one of the former Soviet Union (FSU) countries would do well to learn as much as possible from the research available before entering that arena. To avoid making mistakes others have made, companies should first seek help, as experience is now available.

This article identifies areas requiring extra attention for newcomers and reviews the past decade in order to better illustrate the territory and the business environment within the Caspian area.

Decade in review

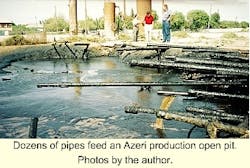

To the surprise of the world and especially the Soviet Caucasus and Central Asia, in 1991, then-Union of Soviet Socialist Republics President Mikhail Gorbachev actualized the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS). The CIS was intended to retain the valuable and complex interchanges between the various member states while, at the same time, releasing absolute Russian control. - Spilled oil in Azerbaijan oil field near the Caspian Sea creates a lake of oil. Photo was taken in 1996.

What actually happened was a rush by most of the former Soviet states to take advantage of the new freedom to solidify their independence from Russia.

Beginning in 1991, throughout the CIS, a massive Western investment surge took place in an effort to benefit from what most felt were enormous opportunities. Since then, only large international organizations and consortiums generally have been able to make much headway in the Caspian region.

However, a number of key events have recently taken place that have improved the environment for midsized and even small operators and service companies to move into the area.

Three phases

To better understand the present situation, it is helpful to review what has happened since 1991. The oil and gas industry has been through three distinct phases in the region:

- The initial phase began with the potential of doing business in the FSU headlined in many journals and conferences. The area was heralded as indeed the new frontier and sure to be a bonanza for Western technology and revenues. However, that phase lasted only a few years, as the realities of operating within the remnants of the old Soviet system became more apparent and operations there proved unworkable for most Western companies. Most of the early entrants eventually pulled out after experiencing large losses. A significant consequence of this phase was to make most speculators wary of the FSU, and enthusiasm changed to pessimism and caution throughout the industry.

- Specific to the Caspian region, a further blow affecting many of the companies who managed to survive the first phase was a series of expensive drilling ventures resulting in noncommercial shows. In Kazakhstan, these included the JNOC (Japan National Oil Co.) well near the Aral Sea, back-to-back wells for Tulpar Munai (then Mobil Corp., now Exxon- Mobil Corp.) near Aktobe, and the OKEC (Oryx Kazakhstan Energy Co., now Kerr-McGee Corp.) Ostrovnaya artificial-island well. In Azerbaijan, two major consortiums completely withdrew after poor drilling results. To worsen the situation, these disappointments hit at a time when the industry was retracting worldwide. Near the end of the second phase, it was almost impossible to attract any serious attention to the region. Many recognized and appreciated the huge reserves and potential, but few wanted to commit money to the region.

- This third-and continuing-phase represents a regional cycle within a global cycle, coinciding perfectly with the worldwide improvement in oil prices. It began with the Shah Daniz natural gas find in Azerbaijan, which was followed by the Kashagan strike off Kazakhstan; these discoveries promise enormous reserves. In addition, the Karachaganak service contracts were finally awarded, and the Caspian Pipeline Consortium began to fill their newly opened line with oil.

From most accounts, the tide has definitely turned, and the future for business looks good. Attention is again turning to the region, and momentum is growing.

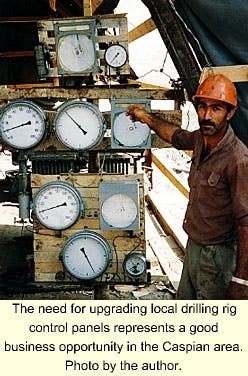

The major projects moving forward demand services, and there is room for competition. The large companies and consortiums should succeed, and now small and midsized companies can vie for a piece of the action as well. Once again, journals and conferences are beginning to expound the virtues of doing business in the region.

Business start-up

When planning first-time market entry or expanding existing business in the Caspian region, companies must understand that the region is still relatively new to Western business practices. There are ever-changing government regulations and cultural-social traditions that impact business development.

The best way for companies to prepare for eventualities is to plan, network, and have more start-up capital than they think they'll need. Following are areas that have been known to trip up Western companies:

- Contract hazards. Contractual obligations can be unclear or inadequately investigated. Many companies have experienced unexpected costs associated with social, environmental, medical, and labor requirements that were camouflaged in initial contracts.

To avoid such pitfalls, companies should always have knowledgeable and experienced advisors to carefully review all legal agreements. Extra protection is offered by using the services of established firms in the area that can provide clarification, predict complications, and deflect issues that could become problems down the road. Liability statements-not always part of agreements today-could become standard as times continue to change.

- Company start-up. Getting everything right during the critical start-up stage will go a long way towards eliminating or at least lessening problems in the future. The following areas are worth extra consideration:

-Start-up costs. The company must have the size and means to support or absorb initial large outlays, or it must set aside sufficient funds for this purpose. Costs can grow rapidly in emerging markets and, too often, attempts to control costs come at a time when spending should actually be increased.

The company must also employ sound initial budgeting, with provisions for start-up outlays. It must factor in a learning curve for figuring out how to get things done and how to function in the new environment.

-Critical documentation. Permits, licenses, and certifications are imperative for legally conducting business in the region. Acquiring the necessary documents from the start will prevent later problems with imports, customs, taxes, visas, and other government requirements. This is also the stage to determine which type of standards-Western or local-will be applied.

For example, will the company use GOST (former Soviet state standard Gosudarstvennye Standarty) or API (American Petroleum Institute) standards? This should be made clear in the certification-permitting documentation. It can be difficult to change even simple things once documents have been submitted and approved.

Services and equipment that will be provided or used further on in a project should be submitted early for approval from the appropriate government agency. It will be easier to work with customs and tax officials if all services and equipment are documented in the original registration, permits, licenses, and certifications rather than trying to get them approved later under duress and time constraints.

These agencies are very good at sensing when a company is under pressure, and they are adept at adding expediency charges. Be sure to allow enough time for such bureaucratic procedures.

-Registration. Before initiating company registration, meet with an experienced source to find out what to expect. Full-service firms such as Pricewater- houseCoopers, Ernst & Young, major law firms, and government-supported efforts by the US Chamber of Commerce and the European Union's TACIS (technical assistance program for CIS countries) can provide comprehensive information and services regarding government requirements and ultimate registration.

Some small law firms and specialty companies have the advantage of speed, lower costs, and superb personal contacts. Obtain good advice to determine where and how best to register the company. The location in which the company is registered can impact taxes, permits, travel, and other elements of doing business in the Caspian area.

The sheer size of the countries and the complications of national travel make registering in the right place(s) a considerable challenge. In Azerbaijan, the registration process is centered in the capital of Baku. However, in Kazakhstan, each oblast has different requirements, and it is important to know what they are before venturing in.

For comparison, most business in Azerbaijan can be conducted within one city, whereas, in Kazakhstan, key centers can literally be 3 hr apart by jet.

HS&E

Successful new start-up companies in the Caspian area also understand and address health, safety and environmental matters:

- Health. Since 1991, health and medical providers with Western standards for heath care have sprung up all over the region. This is a tremendous improvement over the health care that was available even a few years ago.

A popular-and sometimes expensive-option is a subscription service wherein only members are allowed to use the doctors and facilities. Included in this plan is air evacuation for medical emergencies that cannot be handled within the country. This is the recommended approach for new companies.

- Safety. During the first half of the decade following 1991, foreigners could travel throughout the region in reasonable safety. Of course, personnel had to take standard traveling precautions, but, in comparison with many other areas of the world, it was generally safe.

Lost among the decrepitude of the cities now is an appreciation for the safety brought to the country at the strong hands of the Soviets. Ironically, their unforgiving enforcement over a multitude of different cultures, races, and religions following earlier expansionism resulted in extraordinary social control.

Although problems unique to each region continued to exist, they did not expand to foreign business travelers. Now, a marked increase in direct action against foreigners has been recorded within the last few years. The lessening of previously feared Soviet repression (and enforcement), coupled with an increase in criminal forces controlling huge segments of the social strata, makes personal safety a new concern.

As crime increases, security precautions become more critical for offices and employee housing.

- Environmental concerns. It is fairly well known that parts of Soviet Central Asia have been left with horrible environmental disasters.

The Semipalatinsk nuclear test site in Kazakhstan and the abandoned biological warfare laboratories on Vozdrojdenya Island in the shrinking Aral Sea are prime examples. However, hundreds of other, lesser-known sites are also becoming known as being much worse than had previously been believed. Simmering environmental neglect and misuse will produce future catastrophic effects in some cases.

Local content

All former Soviet countries have rules in place that require foreign companies to employ nationals.

Many new companies investing in the Caspian region lack the appreciation of how noncompliance will ultimately hurt them, and they ignore these regulations.

Newcomers would be wiser not to fall into that trap. Neglecting to maximize local labor as soon as possible can create major problems such as having operating licenses revoked. It is best that they plan from the very beginning to source and employ the required percentage of local-content employees.

Using a local company experienced in placing personnel into Western companies would be a good start.

Another source is the local registration department, the same department at which foreign companies are required to register. An important advantage gained from using this source is that it will build a relationship with the very people who control local content quotas. They will appreciate that they have been given consideration, and it will be easier to work with them on labor and other issues.

It is also wise to make most expatriate positions redundant via local replacement as soon as possible. It is important to take this seriously in early planning with management and to submit a plan for such replacements when applying for the company's operating license.

One advantage of working in the region is having an easily trained labor force. Western companies should try to use local institutes to train new employees. Again, this effort will help strengthen local relationships and will make advantageous use of existing local infrastructure. It is best to save out-of-country training as perks and rewards for employees.

One big mistake Western companies make is to concentrate only on those individuals who can speak English. However, many of the most competent and experienced workers do not speak English. As time goes by, more and more locals will be able to speak English as well as Russian and, often, a local dialect as well.

Meanwhile, the ideal would be to employ an English-speaking office manager, one of the most indispensable positions for new companies. Everyone is looking for someone with those qualifications, so it would be wise to locate someone for that position as soon as possible, even before relocating, if possible.

To ensure that the selected local candidates are good choices, companies can provide for a testing period. They should first learn the legal maximum period allowed for a trial period, then schedule midterm and final reviews within that limit to determine if the new hires are performing satisfactorily and to evaluate their progress. Preplanned trial tasks should be in place to measure efficiency. Such a documented procedure can help cull out unwanted candidates before legal restrictions or other obligations take effect.

Taxes, cost overruns

As most indicators continue to bode well for business development in the Caspian Region, some not-so-evident subjects require monitoring when looking to the future.

Ever changing and tightening government regulations and control, for example, will continue to dominate the political and business scene for the near future. Taxes will most likely grow as local governments scheme to extract more and more profits from foreign operators.

As the new Caspian-area republics continue to grow and experience self rule, regulations will constantly change and evolve. Although the governments recognize that foreign investment is the answer to many of their problems, they remain reluctant to give much leeway to foreign companies. Extracting fines is a popular way to generate more revenue for local monitoring agencies.

Unexpected costs also remain a major issue. The increased time it takes to accomplish things causes the most frequent cost overruns. When developing a business plan, new Caspian investors should understand that, in extreme cases, it literally can take them years longer than they expect to move from concept to operation.

A good example of time-money impact is in transportation. Moving materials and equipment into and about the region frequently takes much longer than expected. Direct overland routes often pass through areas of political unrest. Bridges may be out, and roads blocked. Border crossings might take weeks, and, once in the region, companies are faced with ever-changing import regulations.

Again, planning and employing a locally experienced transport company can speed things along. Knowing that a business is going to encounter time and money challenges and preparing in advance to meet them is the biggest advantage in dealing with them effectively.

Civil unrest

The region is beginning to feel internal pressures in reaction to its newfound freedoms. A significant portion of the population also is experiencing hopelessness and desperation while attempting to better their lives.

A distinct division between those who have success and some wealth and those who do not is creating a strong tendency for those left on the bottom rungs of society to become swayed by "cures" promised by radical groups-Islamic as well as others. Serious problems could arise from these movements, carrying with them associated terrorism and threats to Western companies and individuals.

Conversion to Islam in itself clearly is not the problem-rather, it is the recent lure to join radical sects or antigovernment movements such as the IMU (Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan) and Hizb-ut Tahrir, an underground radical party focusing on creating strict Islamic law throughout Central Asia, with its core in the Fergana Valley.

The governments of Central Asia are aware of this growing tendency toward radical conversion, and they are trying to respond. Russia, the US, China, Turkey, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, and others have answered the call for help and are offering assistance by attempting both to impose influence and to keep radical groups at bay.

Unfortunately, it appears that success in solving core problems is not occurring fast enough in areas such as providing better education and creating job opportunities for the people affected.

Corruption

Although corruption is a subject Western management does not like to discuss, it is common in the Caspian countries and therefore must be addressed. Anyone who has worked in the oil industry for long has wrestled with requests for family vacations to Disney World, a new set of tires, and hard, cold cash in order to get equipment out of customs or to be awarded a job.

It would be wise to know a company's stand on bribery and corruption and to inform managers and company representatives how to deal with these requests when they occur.

If newcomers find themselves in situations without good guidance or experience, the best gauge is the "next morning's headline news" rule. In the way of cash handouts, trips to resorts, or gift-giving, if company personnel could not support their actions the next day if the event were plastered in the headlines, then they had better deflect the deal and move on.

Future glimpse

There is no doubt that the national oil companies in each of the Caucasus and Central Asian countries will eventually play even larger roles than they do now. As more locals become highly trained, knowledgeable, and experienced, movement between companies will occur.

Some influential individuals will be attracted to national companies in high positions, so, here again, maintaining close relationships is essential.

Potential for revenue is clearly the attraction in this resource-rich region. During the past 10 years, many improvements have been made, especially in communications and logistics. Many old problems have been solved or, at least, we are better aware of them. Other solutions are sure to follow.

Doing business in the Caspian region is-and will continue to be-challenging, but no more so than in other developing nations of the world. The various governments, workers, and oil and service companies are learning every day how to mutually benefit from the race to get oil to the markets.

The author

Brooks Frazier is president of Caspian Steppes, a Houston-based consultancy focusing on Caspian energy issues. He has worked in the former Soviet Union since 1994, primarily in Caspian and Central Asian countries, including Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Russia, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, and Turkey. He was Caspian area manager for Oiltools (Europe) Ltd. and served as an FSU-region product-line coordinator for Baker Hughes's Inteq division. During his 20 years of experience in the petroleum industry, he has also lived and worked in Germany, Ecuador, Tunisia, Venezuela, and other countries. Frazier received a BS in petroleum geology from Marietta College, Marietta, Ohio.