Offshore Petroleum Operations - Worldwide offshore sector offers major challenges

The long-delayed response to the oil price increase is under way.

Contractors report greatly increased business in long-lead items, ranging from front-end engineering and design (FEED) to offshore vessel design.

The speed of recovery, however, differs by industry sector, and the dynamics seem different from earlier cyclical upturns.

A number of clearly definable macro trends are now affecting the world offshore industry:

- Shallow-water fields are being depleted.

- Huge numbers of small fields are in prospect.

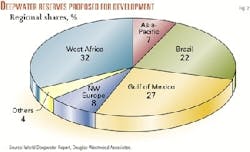

- Deepwater discoveries are growing-particularly in the Gulf of Mexico and off Brazil and West Africa.

- Costs are coming down, due to new technologies and management practices.

- The time to first oil is being reduced-in some situations by up to 50% in 3 years.

- Subsea well numbers are set to double in 5 years.

- There will be a growing use of floating production facilities.

- Main contractors are becoming more involved at the operating level.

- Offshore industry decision-making is consolidating in Houston.

- E-commerce has considerable implications.

- The offshore industry's workforce is aging.

- The offshore sector faces difficulties in attracting and retaining young, talented staff.

- Globalization issues will become more significant.

Continental shelf declining

The major shallow-water areas are now in long-term decline.

In the Gulf of Mexico, the overall oil production trend has been downwards since 1971-72.

The North Sea is now set to follow, with reserve depletions exceeding additions. This year could mark a transition point in the development of the North Sea as, in theory, many fields become fully depleted and reach their end-of-life. The UK sector has the largest number of depletions in prospect (61) during 2000-04 (Fig. 1). However, in practice, depletion dates are often extended as improving technology increases recovery factors.

Decommissioning of facilities is also greatly dependent upon oil prices and the prospects of tie-backs of new wells to existing platforms.

As long as offshore infrastructure remains intact, it can offer the potential of cost-effective tiebacks for new, small fields or remote "pools" of oil and gas in existing reservoirs.

In this respect, the hasty end-of-life removal of platforms and pipelines may be short-sighted.

Smaller new fields

During the 5 years ended in 2000, the Infield Systems database shows that some 458 fields will have been brought into production worldwide. During 2001-05, a further 662 can be identified and-although this is not a forecast-it does indicate the growing numbers of offshore development prospects.

Looking to the future, the picture begins to change. Europe has some significant prospects in 2003, but the major reserve prospects are in the Middle East (the giant South Pars field), off West Africa and Brazil, and, to a lesser extent, in the Asia-Pacific region.

In the past, giant North Sea fields such as Forties and Brent, which had production rates exceeding 400,000 b/d, dominated industry thinking. But the game has changed by an order of magnitude. During 1996-2005, about 94% of all new fields and prospects under consideration are likely to have maximum production rates of less than 40,000 b/d.

The understandable reaction of the oil majors has been increasingly to focus their attention towards the economies of scale offered by the largest prospects, and these mainly lie in the deep waters of the "golden triangle" formed by the deepwater areas of the Gulf of Mexico, West Africa, and Brazil. This process has been greatly aided by increasing confidence in the ability to produce economically from great depths.

For a number of years, deepwater (in this context, >300 m water depth [WD]) has been one of the strongest-growth sectors of the offshore oil and gas industry. Three regions dominate the deepwater prospects: Brazil, the Gulf of Mexico, and West Africa (Fig. 2).

Fig. 3 shows field numbers by type of development. On a historic basis, fixed platforms have been the most popular means of field development. In recent years, however, there has been strong growth in the use of floating production using subsea wells, together with the use of subsea developments as satellites to platforms. The chart clearly shows the linear trends towards subsea, and our global forecasts indicate that the rate of installation of subsea wells will double over the next 5 years.

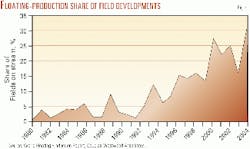

The other global trend is towards floating production.

The past decade has seen considerable growth worldwide in the percentage of offshore fields that use a floating production system (Fig. 4). In 1991, floaters accounted for 2% of fields; in 2001, it could be 27%, and continuing growth seems likely.

Shorter development times

Time to first oil is a critical factor in field economics, and it has been dramatically reduced in most regions of the world.

First production from Brazil's deepwater Marlim Sul field, for example, was achieved in August 1997 through the Marlim Sul-3 well in 1,709 m of water, less than 1 year after its discovery.

In the Gulf of Mexico, development times for deepwater prospects have been cut from 10 years for a discovery made in 1984 to around 2 years for a discovery made in 1996.

This increased speed is very much a function of the application of new technology and management methods, but in deepwater contexts in particular, successful experiences have brought greater confidence and learning curve advantages, which can considerably speed up the development process.

New approaches in project management, especially the trend towards partnerships and strategic alliances between key players, have also impacted favorably on project timescales.

Falling development costs

Following the 1986 oil price slump, a wide range of cost-cutting strategies emerged. These have been substantially reinforced by technological advances that have dramatically reduced capital and operating expenditures both in shallow and deep waters.

Developments in the subsea sector have been instrumental in enabling deepwater projects to achieve cost profiles that are increasingly similar to those in shallow water. Examples include:

- In 1994, development costs for the Gulf of Mexico's Auger field (872 m WD) were $1.1 billion, giving a cost of $5.00/bbl. In contrast, costs for Mars (1996, 896 m WD) and Mensa (1997, 1,650 m WD) were $1.3 billion ($2.50/bbl) and $300 million ($2.50/bbl), respectively (OGJ, Mar. 29, 1999, p. 20).

- In 1973, typical Norwegian development costs were quoted at around $10 million/wellhead, whereas Statoil AS's 1996 cost projections for its Åsgardsgard field (a 59-well development in 280-320 m WD) were estimated at $4.8 million/wellhead. (Although capital expenditure requirements for Åsgardsgard have escalated by more than 37% since then, the increases relate mainly to the export facilities.)

Various initiatives have been launched in the industry, and old ways of doing business are being challenged. The result is that, over the past decade, operators, contractors, and supply companies have become leaner and better able to operate with lower margins than ever before and the offshore oil and gas industry generally has become more robust in response to movements in the oil price. Major changes include:

- Standardization of hardware and field development approaches.

- Partnerships between industry and oil companies.

- Favorable fiscal regimes.

Pipeline activity

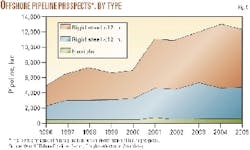

The lengths and type of offshore pipelines laid each year have grown throughout the 1990s and are likely to continue to grow for the foreseeable future.

The oil and gas industry is consistently using subsea technology to exploit field development opportunities, increasing the length of small-diameter flowlines used on individual field developments. At the same time, increasing demand for natural gas is resulting in growing prospects for large-diameter trunk lines worldwide.

There are currently 114 vessels with claimed pipelay capabilities in operation, ranging from large, dedicated deepwater ships down to small barges and multipurpose vessels. Of this fleet, 52% is based in the Gulf of Mexico. The most capable and versatile vessels are increasingly under long-term charter, as the field operators ensure that schedules are not disrupted by a lack of vessel availability.

Although flexible flowlines account for only 20% of the pipe installed, it is a very important and high-tech sector. However, the increasing amount of small-diameter flowlines being laid in deep waters has focused attention on the use of steel catenary risers as an alternative to the higher-cost dynamic flexible lines. Another significant issue are the increasing requirements for insulated flowlines, particularly in deepwater.

Changing business practices

The oil price crash of 1985 prompted oil companies to undertake a major review of their business practices. This process has continued over the past 16 years, justified by the considerable volatility of oil prices.

The overall approach has been to examine carefully every facet of company operations, resulting in new ways of doing business. Parts of operations regarded as unessential have been stripped away-in some instances services ranging from accountancy to field operations have been contracted out to third parties. Field development methods have changed with single-project alliances formed between oil companies and major contractors-the overall aim being to share risk and return.

The response of the contractors has been to offer the oil companies "one-stop shopping," covering all facets of field design, development, and operations. This has been affected by mergers between contractors, joint ventures, and acquisitions of vulnerable companies during oil price down cycles.

The most recent downturn also resulted in a series of oil company takeovers, as Wall Street became the lowest-cost place to explore for oil and gas reserves. (This desire for inorganic growth is also fueled by the fact that size brings greater resilience amid cyclical downturns.)

One factor likely to have increasing impact on suppliers is the emergence of "e-bidding." Prequalified companies have already had to tender by such electronic auctions, where all bids are visible (but unidentified), and the work is awarded to the lowest bidder in real time-the only criteria being lowest price.

Globalization

One significant effect of the recent changes in the offshore industry-the rationalizations, the maturity of the North Sea, and the move to deep waters-has been the tendency for the oil majors to restructure their activities in Houston and from there serve not only the local deepwater Gulf of Mexico but also the growth markets of Brazil and West Africa. In this respect, it is noteworthy that West Africa trade now forms the greatest source of business for the Port of Houston.

The increasing use of low-cost manufacturing centers, combined with the growth in floating production systems, holds considerable implications for offshore industry manufacturers. For example, recently, steel has been priced about $1.00/kg in Chinese yards compared with $2.50/kg in Singapore. Another comparison is average conversion costs (of particular significance to floating production). Using Singapore as a benchmark of 100, the UK is 135, Scandinavia 145, the US 170, and China 60 (Marine Log, July 2000, p. 23).

In the past, there has been a considerable reluctance by some owners to place orders for offshore vessels with Chinese yards due to concerns over lack of technical expertise, infrastructure, and experience. However, there are instances of specialized offshore vessels being built in Hong Kong-owned Chinese yards via joint ventures with US companies. Extending this concept, a number of Chinese and other Far Eastern yards have also been involved in initial prequalification for FPU (floating production unit) and FPSO (floating production, storage, and offloading) vessel conversion and newbuilds through alliances with US and European contractors.

The building of FPSO hulls in Southeast Asia with topsides fitted in Europe for use off Europe is now quite common. However, a recent major success for Western contractors was the award of the Shell Nigeria Exploration & Production Co. Ltd.'s Bonga FPSO project to AMEC PLC in the UK against international competition. This has great significance, as it confirms the continuing viability of using Western project management, design, and fabrication skills to engineer FPSOs for users in Third World markets.

The conclusion must be that globalization must not be treated as a threat but as an opportunity.

Resource shortages

During the most recent downturn, oil companies' attention was focused on integrating and rationalizing their new structures-one factor slowing the response to the oil price increase. Another factor has been that the rationalization of human resources has forced projects to be put on hold, as some oil companies are without sufficient project managers to initiate all field developments in their corporate portfolios.

Contractors also have the same problems-following each downturn the most highly skilled (those that can easily find employment) have left, not to return. This is coupled with the fact that, in the past, the offshore industry has done little to attract young, high-capability people, so human resources are rapidly become the factor limiting the industry's future growth prospects. And training is not necessarily the answer-while skills can be rapidly acquired, experience cannot.

We are concerned that some major contractors may have insufficient capacity (physical and personnel) to undertake more than one or two large-scale projects. At one major contractor, we understand that the average age of a project manager is 53, and the over-45s outnumber under-45s by 12:1. The offshore industry's engineering and design backbone is fast disappearing.

The other factor is offshore vessels. The average age of the total offshore vessel fleet is 20 years, and nearly 30% of the global fleet (1,013 vessels) is more than 25 years old. One result is that much of the existing fleet probably has a fairly limited economic lifetime and is not well suited to operation in the future growth sectors of the industry, such as deepwater and subsea operations. The mobile rig fleet is also aging, and a lack of rigs may also prove a significant limiting factor over the next few years.

Future prospects

Despite short-term regional declines, such as occurred in Southeast Asia in 1998, the demand for offshore oil is set to grow, and gas even more so. Alternative energy may offer great opportunities, but it is most unlikely that this will make any significant impact on offshore oil and gas demand over the next decade or so.

In an industry that will be faced with limited human and physical resources, we see the oil majors increasingly concentrating on large fields in deep waters, leaving a huge number of opportunities for smaller players who can offer ways of profitably producing from sub-40 million boe fields. The main requirement will be to develop highly systematized approaches using standard field development "modules" that have a minimum requirement for re-engineering-and all the skills that entails.

The author

John Westwood heads the industry analysts Douglas-Westwood and over the past 15 years has been responsible for more than 160 specially commissioned oil industry business studies for clients worldwide. He previously spent 12 years in the offshore contracting business, working on projects for many of the world's major oil companies and has served on the boards of offshore industry companies in the UK and Norway.

Westwood has published more than 50 papers on various aspects of the oil and gas industry and is a regular speaker at energy industry conferences and investor seminars worldwide.