Rapid growth in deepwater Gulf of Mexico production will seriously affect all segments of the North American oil industry in the coming years.

Deepwater exploration and production, defined by the US Minerals Management Service (MMS) as that located in water depths of 1,000 ft or greater, has become technologically and economically feasible within only a few years. And technology is continuing to advance rapidly.

Changes are on the horizon for deepwater producers, ranging from regulatory action to allow the use of floating production, storage, and offloading (FPSO) vessels to resolution of economic and logistic issues associated with marketing the new production.

How will the US crude oil market react to the coming production increases? Clearly, new infrastructure must be built and new supply relationships established. The path of future production is still uncertain in terms of both crude oil volume and quality.

A review of the fundamental supply trends gives an indication of the direction and magnitude these changes will have on the pipeline and refining industries.

Deepwater production outlook

The MMS has revised projected reserves for the Gulf of Mexico's outer continental shelf (OCS) to more than 37 billion bbl of oil. Deepwater production currently contributes more than 50% of total Gulf of Mexico production vs. less than 20% of the total only 5 years ago.

Deepwater production will play a major role in supplying US energy needs in the coming years. Purvin & Gertz' projections suggest that deepwater production could account for one third of total US domestic crude oil production by 2010, meeting more than 10% of US supply requirements.

For production to increase as projected, however, technological advancement will have to continue.

A similar process occurred in the development of the shallow gulf. Kerr-McGee's Ship Shoal Block 225 discovery in 1947 was drilled in water less than 20-ft deep, yet that find initiated a wave of discoveries which averaged 1 billion bbl/year for the next 30 years (Fig. 1).

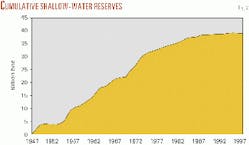

Reserve-addition rates began to decline in the late 1970s, causing cumulative reserves to level off (Fig. 2). If deepwater reserves follow a similar path, then many years of deepwater success should lie ahead (Fig. 3).

More than 150 deepwater discoveries have been announced in the gulf, with total reserves of more than 12 billion boe. Twenty-two fields have announced reserves in excess of 200 million boe. Most of these finds have yet to enter production; therefore, a number of factors must be considered in developing the future production profile.

For deepwater fields, the time lag between discovery and production has ranged from more than 10 years to as little as 2 years. The shorter time intervals have been achieved by planners' taking advantage of existing infrastructure, with the longer intervals resulting from early discoveries that occurred before development technology had sufficiently advanced.

Even though the growth of deepwater infrastructure and experience will tend to reduce the future lag between discovery and production, the continued advancement into deeper and more remote areas will have the opposite effect.

Typical production profiles for individual deepwater fields are somewhat different than typical shallow-water fields. The ramp-up of deepwater production is steeper and peaks earlier, resulting in shorter overall production cycles than shallow-water fields.

While this production profile provides for steeper increases and decreases for individual fields, the outlook for future discoveries determines the long-term aggregate production profile.

The total reserve endowment, the size and pace of discoveries, and individual field development and production profiles will all determine the ultimate peak and duration of Gulf of Mexico production. Based on Purvin & Gertz' assumptions for these factors, deepwater production should continue to increase at a rate of 150,000 to 200,000 b/d annually for the next 5 years before production begins to plateau.

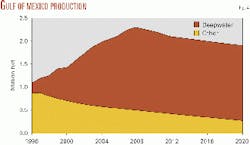

Peak deepwater production will take place 6-9 years from now. Declining shallow-water production will partially offset deepwater increases, reducing total gulf output increases to around 100,000 b/d. Fig. 4 shows that total Gulf of Mexico production will reach 2.3 million b/d at its peak, an increase of roughly 900,000 b/d from current levels.

The projected peak and subsequent decline to a longer-term plateau is the result of the anticipated start-up of a large number of recent sizable discoveries. If discoveries continue at the pace experienced in the past few years, the peak could be delayed significantly, and higher production levels could be attained.

Deepwater crude quality, value

The deepwater surge has already changed the nature of Gulf of Mexico production. Much of the deepwater discoveries have been sour crudes as compared to the light-sweet crudes common in the shallow waters of the gulf.

These changing qualities will require the development of new markets for gulf producers as production expands, since the Gulf Coast refining industry still requires about 30% light-sweet crude in its slate. Due to infrastructure limitations (discussed later), competition for market outlets may be fierce.

Cooperation and planning are paramount in the development of commoncarrier pipeline systems in which one producer's oil is commingled with many others and then sold as a common grade.

At this early stage in deepwater development, it is too early to determine the overall quality of future production with any certainty. Based on current trends, future deepwater discoveries are expected to be predominantly sour, with many having relatively high metals content and total acid numbers.

These qualities will also affect crudes' market values, and producers will gain from an understanding of their impact on refining values and crude marketability.

The overall supply and demand balances for the Gulf Coast and US Midwest indicate that sufficient medium-sour refining capacity is present to accommodate the future deepwater production.

Greater proportions of sour crude in the future production mix, however, will cause greater disruption to current distribution patterns. If more future deepwater production is sweet, existing pipeline systems will more easily accommodate the growth in production.

The quality of crude oil directly affects its price in a competitive market. Much of the deepwater production to date has been a medium-sour grade. This eliminates some refiners as market outlets.

Refiners should become aware of the developing trends in Gulf of Mexico crude quality to prepare for future supply arrangements and processing opportunities as deepwater production increases.

Producers should also prepare for the marketing of their crudes by understanding the determinants of value for refiners. In addition, producers must ensure that production is valued properly when shipped in common-stream pipelines, and that it is not unfairly discounted by other production.

Pipeline quality banks are designed to compensate (or charge) shippers for the difference in value between the oil they inject vs. the oil they receive. As future fields of uncharacterized qualities are discovered and enter production, existing shippers may be faced with substantial changes in quality bank structures, some of which may adversely affect the value of their production.

FPSOs on the horizon

The MMS's environmental impact statement concerning FPSO use cited the risk of oil spills to be comparable to those from other deepwater systems and from pipelines.

A public comment period has passed and a final decision to approve FPSO use for deepwater production in the Gulf of Mexico is likely. Applications will be reviewed by the MMS based on site-specific plans before individual projects can receive final approval.

The incentive for a producer to use an FPSO as opposed to conventional pipeline transportation has yet to be determined. A project's feasibility can change dramatically in deeper water where increased pipe wall thickness and undersea installations become more costly.

FPSO use may play a key role in enabling the development of ultra-deepwater fields that are far from existing pipelines.

There has been speculation that FPSOs may prevent price discounts on crude that otherwise would be shipped in pipelines that deliver into limited market outlets by providing the added flexibility of shuttle tankers that can serve more than one market.

While this flexibility will be valuable to those developments using FPSOs, the economics of pipeline transportation are likely to discourage FPSO use in projects with reasonable pipeline alternatives. Each project will have specific issues that must be considered in total before development decisions can be made.

Deepwater infrastructure, distribution

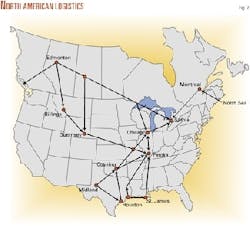

There are three main refining regions for the disposition of crude from the Gulf of Mexico: the Louisiana Gulf Coast, the Texas Gulf Coast, and the Midwest.

The Louisiana and Texas crude corridors primarily serve these three markets. The Midwest is also served by Canadian imports that can and will constrain the amount of domestic production that will be processed in this region.

The capability of these corridors to distribute the increasing production to the refiners that can process it is the most critical issue determining the future distribution patterns for deepwater crude oils.

Some of the larger fields, such as Shell's Mars field and ExxonMobil's Diana/Hoover fields, have been developed with new pipeline systems to handle the large volumes of production. These examples include the Mars pipeline and the Hoover Offshore Oil Pipeline System (HOOPS), which are capable of moving 500,000 b/d and 200,000 b/d, respectively.

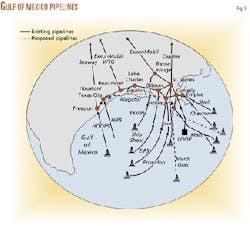

Fig. 5 shows the major offshore oil pipelines that serve both shallow-water and deepwater producers.

Even though geographical locations of the fields will often dictate the natural market for the oil, some field locations have options to route production to multiple trading locations. Such flexibility can be quite valuable to producers.

An example of the value of this type of flexibility occurred last year when a barge incident shut down the Poseidon Pipeline. Almost immediately, producers were able to swing over 140,000 b/d of Poseidon into the Amberjack/Mars systems, maintaining production levels and operating cash flow.

Louisiana corridor

Today's offshore infrastructure is clearly inadequate to accommodate the current group of known discoveries under development if produced without new investments in offshore pipeline capacity.

The Louisiana corridor will be seeing the greatest pressure in the next few years as new discoveries are brought online while investments in offshore infrastructure are made in parallel.

For example, production from fields contributing to the Mars pipeline common stream is now about 400,000 b/d. As Crazy Horse and other fields enter production, the production in the areas served by the Mars system will exceed 1 million b/d.

BP has announced plans for the new Mardi Gras pipeline system to move up to 1 million b/d from deepwater fields off the eastern region of Louisiana. Along with other fields, this pipeline system will serve the Crazy Horse and Crazy Horse North discoveries with announced reserves of 1.5 billion boe.

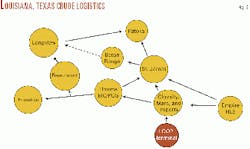

The major Louisiana onshore pipeline systems (Fig. 6) will see changes in crude quality as domestic production grows. Louisiana Offshore Oil Port (LOOP) is investing in tankage at Clovelly where it currently has salt dome cavern storage.

Staging of both imports and domestic production will then be provided to connecting carriers.

St. James is a major trading point in Louisiana that receives crude from LOOP via LoCap pipeline, ExxonMobil, Equilon, and others. While the pipeline capacity leaving St. James is quite substantial, it has been fully utilized in recent times. The Capline system has routinely run near its capacity of 1.1-1.2 million b/d.

A new route for crude to move from St. James to the Midwest market is now coming into existence, however. The ExxonMobil pipeline from St. James to the Baton Rouge refinery is being connected to the reversed ExxonMobil North Louisiana pipeline. This line, which previously moved crude south to Baton Rouge, will provide service to the Midwest via Baton Rouge and Longview en route to Patoka.

Texas corridor

The lesser-developed deepwater regions offshore Texas also hold great promise, as shown by the Diana/Hoover and Boomvang/Nansen discoveries. The area is served by the Hoover Offshore Oil Pipeline System (HOOPS). It has a current capacity of 200,000 b/d to the Freeport area.

From Freeport, crude can move on to the Houston-area refineries as well as the Midwest refineries through the Seaway Pipeline.

While the current outlook does not indicate the same level of tightness in offshore pipeline capacity in Texas as in Louisiana, significant new discoveries will also bear a large burden for infrastructure investment.

Transfers

Production from Louisiana can reach Texas refining markets through the Equilon Pipeline system. This system runs from Clovelly, where Mars blend is traded, through Houma, where the Poseidon and Eugene Island streams are traded.

From Houma, it continues through the refining centers at Lake Charles, the Port Arthur-Beaumont-Orange area, and the Baytown-Houston area.

This need to balance Louisiana's increasing offshore supply with market outlets beyond the state has led to the proposal by Enbridge and LOOP to construct the $400-million Alligator pipeline to connect with the Texas market, with a capacity of 600,000 b/d. Approval and financing for the project are still being pursued.

The need for such a project will depend on the timing and duration of peak offshore production, the quality of future deepwater crudes, and the remaining level of imports through the Louisiana corridor.

Impact on US crude markets

The impact of deepwater production on US crude distribution patterns must be viewed in the context of local, national, and global trends in refining and crude supply.

In recent studies, Purvin & Gertz has analyzed future crude production trends in North America and around the world, the future demand for refined products and crude oil, refinery capabilities and investment requirements, and future changes in global crude oil trade patterns.

Deepwater producers will be affected by these forces, as will the refiners who purchase their crude oil.

As the growing production from the Gulf of Mexico makes its way into existing markets, incremental imports will be backed out. As production increases, more imports will be affected.

The growth of medium-sour crude production in the Gulf of Mexico, partially offset by declining light-sour crude production in the inland regions, may displace up to 900,000 b/d of offshore imports over the next decade. This process has limits, however, because not all imports can be displaced by domestic production.

Some volumes are being supplied to refiners that are partly owned by the supplier. Other imports are needed for specific quality reasons, such as the production of lube base oils or as feedstock to residual desulfurization units.

These commercial relationships and quality requirements determine the minimum structural levels of imports that can be expected to prevail in any region.

If growing deepwater production pushes imports down to minimum structural levels, producers will find that discounts will be required to allow production to flow to other markets.

Due to the tight integration of the Midwest supply system with the Louisiana Gulf Coast pipeline network (Fig. 7), those two regions are critical in determining the future distribution of Gulf of Mexico production.

The balance between minimum medium-sour crude import levels and increasing production from the Gulf of Mexico will define future price relationships for deepwater sour crudes vs. other domestic and international crude oils.

In the US, deepwater producers will face growing competition from Latin American heavy-sour crude suppliers as well as from Canada. Over the past decade, US refiners have processed steadily increasing volumes of heavy-sour crudes.

This trend has accelerated in recent years as Latin American heavy-sour crude producers have participated in projects to add processing capacity to Gulf Coast refineries. Production of Latin American heavy-sour crudes is also growing rapidly, and the Gulf Coast is the most advantageous market for these producers.

In spite of the surging Gulf of Mexico medium-sour crude production, most of the growth in crude runs on the Gulf Coast will be heavy-sour grades, often processed in projects with contractual or equity incentives from producers.

In the 1990s, light-sweet crudes were displaced in many refineries by both heavy and medium-sour crude runs. Due to refinery processing constraints, light-sweet crude runs now have only limited capability to fall further without significant investment.

In addition to coping with changing crude qualities, refiners will have to invest in the production of lower-sulfur fuels in an environment of tight capital availability.

As a result, light-sweet crude refiners will have limited incentive to convert to medium-sour grades. If refiners are changing crude slates, full conversion to heavy-sour grades will generally be favored. The deep gulf's medium-sour crudes will face a market of restricted growth and must compete to displace imports from the US.

Purvin & Gertz analyzed the future disposition of deepwater crude by reviewing future refinery runs and quality in the regions served by Gulf of Mexico crudes, future Canadian supplies, and structural import levels.

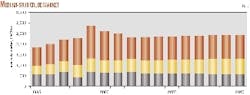

Fig. 8 compares projected Gulf of Mexico medium-sour crude production to the markets available in the Louisiana Gulf Coast, the Midwest, and the Texas Gulf Coast, after accounting for the minimum levels of structural imports.

Medium-sour runs rose steadily in the late 1990s and surged in 1999 when heavy-sour crude production fell in response to low prices and OPEC's production restrictions. As heavy-sour crude projects come onstream over 2000-2002, medium-sour runs are expected to fall. Only modest growth is anticipated in 2003 and beyond.

The volume of medium-sour Gulf of Mexico production will exceed available markets in the Louisiana Gulf Coast and Midwest, and thus some portion must move west to the Texas Gulf Coast market. The need for these movements implies that sour crude prices in Louisiana must be lower than Texas prices to create the incentive for crude to flow.

Future bright, outlook tight

Deepwater discoveries have been concentrated in the regions of the Gulf of Mexico tributary to the Louisiana distribution corridor, even though increasing success has been seen in Texas waters.

With reasonable expectations for future discoveries, the existing distribution infrastructure in the Louisiana corridor appears to be very close to capacity in the future.

Investment in both onshore and offshore systems will be required to relieve bottlenecks and system constraints.

The changing face of Gulf of Mexico crude production will affect all producers, transportation companies, and refiners, and all must be prepared to face the challenges and opportunities that follow.

The authors

Blake T. Eskew is a vice-president in the Houston office of Purvin & Gertz Inc. His experience at Purvin & Gertz has focused on energy market analysis, strategic business analysis, and acquisition and project development assistance throughout the midstream and downstream industries. Eskew holds a BS in chemical engineering from the University of Texas, Austin, and an MBA from Columbia University.

Stephen L. Jones is an associate in the Houston office of Purvin & Gertz Inc., where he has focused on crude oil marketing and supply issues and short-term energy market analysis. Jones previously worked for Exxon in a number of operations, economics, and planning positions, and holds a BS in civil engineering from Tulane University.