Russian fiscal terms may need wider range

Oil and gas tax reform in Russia is heading in the right direction. Further reform is needed. Canadian resource management practice offers a particularly appropriate model for application to the Russian situation.

This article assesses the economic effects of recent efforts aimed at reforming the tax and other fiscal terms applicable to the upstream petroleum sector in Russia. Three sets of terms are compared:

- "Existing," the current generally applicable royalty terms;

- "Reform," the existing terms with proposed reforms; and

- "PSA," the currently applicable production sharing contract terms.

To provide some international context, the applicable terms for Canada are also considered. Since natural resources in Canada generally fall under provincial jurisdiction it was necessary to select representative Canadian terms. For this purpose the terms selected are those applicable in Newfoundland and Labrador (NL) and in Nova Scotia (NS).

Both the Russian PSA terms and the Canadian terms selected contain important rate of return (ROR) features; and, applying to northern and offshore operating environments, the Canadian terms may be of interest to Russian authorities as they proceed to address resource management issues applicable to the development of the vast untapped resources of their northern and offshore frontier.

Assumptions

A "representative" 366 million bbl oil field in the Timan Pechora region of Russia is taken as the point of reference for comparison. Production is assumed to be sold at $19(US)/bbl. Unit costs are investment $2.70/bbl, operating $3.25/bbl, and transport $3.41/bbl.

Fiscal terms are:

Canada, Newfoundland & Labrador:

Income tax 43.12%, sliding scale royalty 1-7.5%, based on production.

Resource rent royalty 20-30% after compound RORs of 13% and 23%.

Canada, Nova Scotia:

Income tax 45.12%, sliding scale royalty 2%, and 5% after a simple ROR of 13%.

Resource rent royalty 20-35% after simple RORs of 28% and 53%.

Russia, "Existing:"

Income tax 35%, royalty 6-16% (assume 8%), Mineral Replacement Tax (MRT) 10%, excise tax 0-50¢/bbl, export tax 27¢-$6.50/bbl, road tax 2.5%, housing tax 1.5%, asset tax 2%, currency conversion tax 1.3%, and payroll tax (various social-related leview) 38.5%.

Russia, "Reform:"

Modified "Existing:" Depreciation periods shortened, royalty 0-16% (assume 6%), MRT phased out, road tax rate reduced to 1%, and housing tax eliminated.

Russia, "PSA:"

Income tax 35% but levied on Investor's Profit Oil share. Royalty 6%. PSA terms: Rates beginning at 20%; and then 40%, 50%, 60%, and 70% after RORs of 24%, 26%, 28%, and 30%. Payroll tax 38.5%. All other levies are not applicable.

Note: Since PSAs are negotiated the various rates are not prescribed in legislation. The rates assumed here represent actual practice for a project in the Komi region, as recorded in "World Fiscal Systems for Oil and Gas-1997," by Van Meurs and Associates, Calgary.

Fiscal outcomes

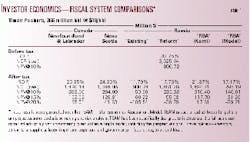

In reference to Table 1 it is interesting to note that:

- At $1,481-1,495, the after-tax real NCF is very similar under both the Russian "Reform" and "PSA-Komi" terms. These results are also comparable to those under the NL system ($1,490).

- The existing Russian system reduces an otherwise attractive 32.75% ROR project to being marginal to uneconomic (NPV in the range of $51-60). This result is more dramatically confirmed by considering the burdened and unburdened NPV results: Under the "Existing" system the investor receives only 51/867 = 6% of the discounted barrel, whereas the Russia "PSA-Komi" and Canadian terms yield 34-39%.

- At higher discount rates, only the "PSA-Komi" terms (e.g., NPV of $117.70) compare with the Canadian terms (e.g., NPV of $128.81). This results from the progressive nature of ROR-based systems and the front-end loading of the royalty-based "Existing" and "Reform" systems.

- An important observation that is often not recognized, and that may not be apparent to the reader, relates to the "Existing" terms. These terms are heavily burdened by the MRT.

It should be observed that this tax is intended to compensate the state for having invested in resource exploration. As such, some portion of the relatively high government take in Russia is justified as compensation for opportunity cost and for having taken prior exploration risk.

This said, however, for new ventures with the full exploration burden, the existing system is not competitive. This of course is not news and is certainly reflected in the industry debate in Russia and in the ongoing Russian initiatives aimed at fiscal system reform. - Both the "Reform" terms and the "PSA-Komi" terms record a significant improvement in investor economics. The progressive nature of the "PSA" system is shown by the improved NPV results for the company at higher discount rates.

- The "PSA-Model" terms are in fact more onerous than the "Reform" terms. This would seem to be explained by an assumption that the precise "Model" terms are illustrative and not intended for actual application.

Sensitivity analysis

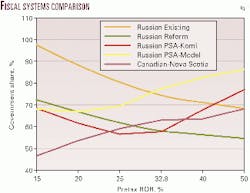

Table 2 and the associated Fig. 1 compare government's share of operating revenue for modeled projects with pre-tax real RORs ranging from 15-50%.

The first observation is that only projects with a pre-tax ROR greater than 15% are modeled here. This is because under lower ROR cases comparison is made difficult as the Russian systems generally yield nonsensical results, in many cases seeing government take at more than 100% of operating revenue.

Of course in these cases project development simply would not proceed. In fact, an assessment of the investor NPV@10% shows that the Russian fiscal terms are precluding many projects with RORs below 20-25%, whereas this threshold internationally is more in the order of 10%.

Russian authorities are well aware of this situation, their current actions being guided by the realities of an abundant and attractive resource base and by the need to recognize past investments that have been funded by the Russian people.

The ideal fiscal system should be progressive. This means that it should take more for government as project profitability increases. Only the Canadian systems meet this important criterion across the full range of cases modeled.

This said, it does appear that there is room for the NL system to perhaps take a little more as profitability increases. By comparison, the Nova Scotia system takes a progressively higher share across the full range of projects modeled. Of course, the overall level of government take must be commensurate with the risks and potential rewards for the area under consideration.

The Russian systems can be generally described as regressive. The "Existing" system takes 68% from high ROR projects; however, when profitability decreases the take in fact increases to 97%, the reverse of what is needed to attract increased investment.

While the "Reform" proposal represents a definite improvement on the general terms, it is still regressive and its overall level of fiscal burden is still too high. For the vast majority of investment alternatives (those with lower RORs) a government share of 65-75% is simply not competitive.

The "PSA" terms are likely achieving their intended result. One of the arguments in their favor is that they help achieve the level of fiscal system stability necessary for go-forward investment decisions without having to wait for the more general reforms to move through the Russian DUMA. On this criterion the PSA system has certainly been a positive development for both industry and government.

The "PSA" terms can also be considered successful on another level. It would appear obvious that an ROR-based system would offer a significant administrative burden were it applicable to a large number of projects. Russia certainly fits this category, being the world's largest gas producer and third largest oil producer.

Knowing that the system would likely not be applied generally, and wanting to attract early investment capital, the PSAs would seem to be designed to apply to a limited number of selected and highly attractive projects. The system can be quite progressive for projects with pre-tax RORs above 20%. For projects with RORs between 20-50%, government take (under the Komi terms) increases progressively from 56-77%. These rates are still too high for general application.

Conclusions

Russia certainly has an attractive resource base. While many fiscal and legal reforms have not proceeded as rapidly as hoped, the application of the "PSA" structure has allowed limited investment to proceed. Also, the reforms being proposed are certainly significant-lowering the government take on lower ROR projects from 97% to about 72% and in other cases to less than 60%. This said, additional reform is still needed.

Future fiscal reform in Russia's petroleum sector must find a way of managing a huge number of projects that are at various stages in the exploration-development-operating cycle: Some are existing producers, some have only recently been discovered, some are in the development phase, and some are legitimate exploration targets. It goes without saying that many of these projects offer very attractive pre-tax economics.

Faced with the necessity of applying significant and broad-based reform to a petroleum industry with a very long and successful history, Russia is confronted with the challenge of designing a fiscal regime that manages "Old oil," "New oil," and "Future oil."

The lesson for Russia is that one all-encompassing system is impossible. The industry is big, it is significant, it has a long history, and it is in transition. In this context the experience of Canada's premier producing province, Alberta, would seem to be particularly applicable.

While the ROR-based systems may be of interest and may find specific application, the long and successful history of Alberta's petroleum industry has made it necessary for this province to be practical and to design a system that recognizes a large and dynamic industry that is characterized as containing "Old oil," "New oil," and "Third-Tier oil." This would seem to be an important recognition that needs to be incorporated into Russia's reform process.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Natalia Khaltourina, chief manager-investment policy, at Slavneft Vostok Co., Moscow, and TEAM partners Brian Hemeon and Wade Locke, St. John's.

The author

Barry Rodgers is a petroleum economist living in Calgary. He specializes in upstream project financial analysis, fiscal system design, and benefit-cost analysis. Before starting an international consulting career in 1997 he was director, energy policy with the Government of Newfoundland and Labrador, working on projects such as Hibernia and Terra Nova and on the design of the province's onshore and offshore royalty systems. Since 1997 he has completed numerous studies related to Russia's upstream sector. He is a graduate of Memorial University with concentrations in economics and mathematics. He recently completed a master's degree in liberal arts. E-mail: [email protected]