Future US regulations, product demand will tighten fuels market

In the future, three themes will continue to dominate the US refining scene: ownership restructuring, clean fuels, and price volatility. These factors combined with increasing demand will tighten the supply of gasoline and diesel fuels until more fuel-efficient vehicles become popular.

As they report record earnings for the past year and enjoy plentiful crude-oil feedstocks to run their refineries at capacity, US refiners face many uncertainties.

- Who will own US refineries in the future? Will integration in the petroleum industry disappear as independent refiners advance to the head of the class?

- Will the Bush administration provide relief to US refiners regarding future diesel fuel specifications-either by delaying implementation or relaxing sulfur minimums?

- In the face of demand growth for clean products and more stringent specifications, from where will the capital come to build additional capacity and upgrade current processing capabilities?

- What technology should be employed to meet new stringent product specifications? Are there grassroots refineries on the horizon that will feature best-available technology?

- What will future motor gasoline specifications be? Will EPA eliminate the requirement of oxygenates?

- How will refiners ensure secure and economical sources of energy supply for plant operations?

Historical overview

Refining capacity experienced three distinct phases in the past 30 years: expansion, rationalization, and ownership restructuring.

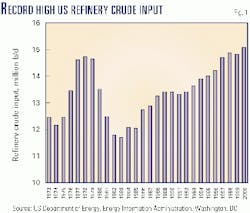

The booming economy of the 1970s spurred increasing demand for refined products. Refinery crude-oil input climbed to a peak in 1978 (Fig. 1). The growth in product demand brought forth an expansion of refinery capacity in the 1970s, while the "entitlements" provisions of federal law encouraged the growth of small-scale refineries.

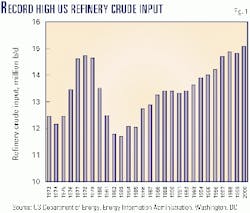

The number of refineries continued to grow after the turndown in products demand. The number of operable refineries peaked at 324 in 1981 (Fig. 2).

That same year, refinery utilization fell to its lowest point in history at 68.6%, a clear signal that the growth phase of the 1970s was over.

Throughout the 1980s, refineries shut down, and refiners went out of business even though refined-products demand was on the rise. Refineries continued to shut down during the 1990s, but the survivors expanded their processing capability through capacity creep, leading to a net increase of 1.1 million b/d of capacity during the past 10 years.

Product demand, however, grew faster than capacity additions. By the early 1990s, refinery capacity utilization was consistently above 90%. More recently, operating rates have been near 95%.

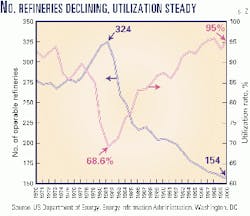

As overcapacity, poor margins, and the demands of environmentally based capital investments drove refiners from the industry, the economic value of refineries fell precipitously. Resale values averaged about 10¢ on the dollar compared to replacement cost during the early 1990s.

An upward trend is now in place, however. Resale values rose from a low of 2% in 1993 to 28% in 2000 (Fig. 3).

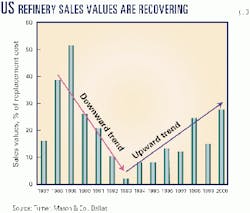

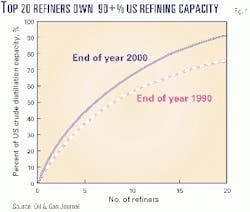

As the number of refineries decreased, so did the number of companies involved in refining. At the end of 2000, 20 refiners accounted for 91.5% of US crude-distillation capacity compared with 75.2% at the end of 1990 (Fig. 4).

The combinations of Chevron Corp. with Texaco Inc. and Phillips Petroleum Co. with Tosco Corp. will further boost that concentration.

Ownership realignment

Realignment of ownership with more capacity concentration will continue during the next 1-2 years. Also, the number of refineries owned by foreign companies or independent refining companies will increase.

General realignment

With its recently announced $7 billion acquisition of Tosco and its previous purchase of BP's Alaska production, Phillips increases it rank among major oil companies.

BP has three of its US refineries, totaling 177,000 b/d of capacity, up for sale.

Chevron and Texaco are in merger negotiations and have already filed a statement with the Federal Trade Commission that they intend to divest Texaco's Motiva Enterprises LLC and Equilon Enterprises LLC refining assets. Royal Dutch Shell and Saudi Refining, a division of Saudi Aramco, have announced they will buy Texaco's stake in their downstream joint ventures, pending the results of the proposed Chevron-Texaco merger.

Texaco currently owns 44% of Equilon with Shell holding the balance. Motiva is owned 31.6% by Texaco, 31.6% by Saudi Refining, and 36.8% by Shell.

Foreign ownership

Royal Dutch Shell, BP, TotalFinaElf, Saudi Aramco, and Petróleos de Venezuela SA (PDVSA) are major foreign owners of US refining capacity.

Non-US ownership rose from 19.1% at the end of 1990 to 23.7% at the end of 2000. It is likely to increase in the near future.

The motivation for foreign ownership is not that the US refining industry is perceived as a high profit, growth business. Foreign interest is motivated by a desire for a secure outlet for the foreign country's crude production, especially those countries with heavy, sour crude.

To the degree that Texaco's refining assets are divested, Saudi Arabia is likely to increase its US refining industry presence.

PDVSA has a major presence in the US through its ownership of Citgo and several other refining joint ventures. It recently announced a desire to form a joint venture with a major asphalt supplier in the Midwest and an asphalt refinery on the West Coast and possibly to acquire or secure a long-term operating agreement with a refinery in Texas.

Petróleos Mexicanos (Pemex) has a 50% interest in Shell's Deer Park refinery. It has close ties with several other refiners through supply agreements for Maya crude. Pemex is aggressively seeking new outlets for its heavy crude, and recently added Orion Refining Corp., Norco, La., to its portfolio.

Russia's Lukoil just completed its acquisition of Getty Petroleum's service stations. Lukoil said the purchase marked the beginning of Lukoil's expansion into the US market. Lukoil is likely giving some thought to a US refining presence.

Norway is also a candidate. Although it has not made any overtures, Statoil is restructuring. The company already exports refined products to the US market and has had several tolling agreements with US refiners.

Another possibility is Kuwait. Although it has not made any specific US overtures to-date, preferring to concentrate expansion efforts in Europe, a move into the US market is not unlikely.

The problem with an increasing foreign ownership scenario is that refineries that are coming on the market as a result of the investment hurdles of upgrading to clean fuels may not present a strategic fit to a foreign producer.

For example, Farmland Industries Inc.'s 95,000-b/d Coffeyville, Kan., refinery is for sale, and Premcor Inc. shut its 80,000-b/d Blue Island, Ill., refinery on Jan. 31, 2001. Both companies cited the expense of clean-fuels regulations as deciding factors.

Independent refining companies

At the beginning of 2001, independents owned about 64% of US refining crude capacity vs. 51% 10 years ago. This situation is the result of aggressive expansions through acquisitions by companies such as Tosco, Valero Energy Corp., and Ultramar Diamond Shamrock Corp. (UDS).

At the same time, the integrated oil companies are forming alliances to spin off their refining assets into separate limited-liability companies. It is too early to judge the economic benefits of these alliances, but so far the results have generally fallen short of expectations.

Phillips had this same alliance mindset. The company formed a joint venture with Duke Energy Corp. for its natural gas gathering business and a joint venture with Chevron for its chemical business. It was unsuccessful in finding a refining partner after discussions with Conoco and UDS.

The pending acquisition of Tosco would make Phillips the second largest American refiner in the US. The deal appears to be structured so that Tosco's management will be in control of the refining and marketing businesses.

Should the managers retain Tosco's opportunistic style, the company may increase its downstream presence. This strategy would be counter to the trend of the other integrated majors, which are focusing more of their budgets on exploration and production than on downstream businesses.

Overall, it is unlikely that any of the large integrated major oil companies will buy refinery capacity in the future unless there is a unique strategic fit. Shell is reported to have the right of first refusal on any sale of the Texaco interests. The FTC may not allow a full buyout of Texaco's shares, however, thus prompting some buying interest from the independent refiners.

To the degree they can continue to borrow money, the independents will have an increasing share of the US refining market. The capital markets should be receptive, as the recent run of good profit margins has caught the attention of Wall Street investors.

J.P. Morgan Securities issued a research bulletin in December titled, "Remain Bullish on Refiners," which surveyed several independents. In January, a Merrill Lynch research report on US refiners carried the subtitle "Upside [earnings per share] Surprises Could Continue For Years."

New refinery potential

Grassroots refineries have not been built in the US for more than 20 years. Profit margins have not been attractive, and there has been a ready supply of older refineries available at deep discounts to replacement cost.

Most industry observers would argue it is unlikely that a new grassroots refinery will be built in the US within the next 10 years, if ever. Profit margins have not been attractive, even during the good times, and environmental concerns are a strong disincentive.

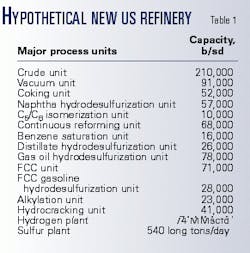

On the other hand, one can imagine a case for the construction of a large, state-of-the-art refinery designed to make low-sulfur fuels. Using our refinery-modeling program, Turner, Mason & Co. has studied a hypothetical new Gulf Coast refinery with a capacity of 200,000 b/cd using Arab Medium or Mars crude.

The refinery is a high-conversion facility with appropriately sized cracking, alkylation, coking, and hydrocracking units, and the other processing units necessary to make Tier II gasoline and 15-ppm sulfur diesel (Table 1). All of the units are based on commercially proven technology.

The overall cost of the refinery and off sites is $2.5 to $3.0 billion. Assuming a WTI crack spread of $6/bbl and a Mars/Arab Medium to WTI discount of $7/bbl, the hypothetical refinery would have an adequate payout.

Both of these key price assumptions are within the realm of recent experience and could hold up in the future. Although a $6/bbl crack spread is unsustainable in today's marketplace, it is more tenable as capacity utilization approaches 100%.

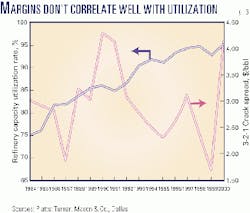

Although high capacity utilization combined with fewer competitors and increasing product demand usually makes for a high-profit-margin scenario, this has not been the case for the refining industry.

Despite economic theory, refining margins do not correlate well with capacity utilization (Fig. 5). The tightness of that correlation should change in the future as refinery capacity tightens; thus, economic theory may still prove correct.

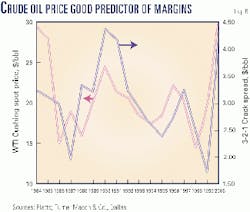

The price of crude oil has been a better predictor of refining margins, however. As shown in Fig. 6, refined products prices have historically reacted to changes in crude-oil prices in both directions. Falling crude prices lead to even sharper declines in refined product prices and vice-versa.

Capital investments

The US refining industry faces three major capital investment challenges during the next few years: gasoline sulfur reduction, diesel-fuel sulfur reduction, and reformulated gasoline (RFG) production.

Each of these will require a unique set of investment decisions for practically every US refiner. Unfortunately, many of the required investments have limited overlap in regard to types of processing units and configurations.

Premcor cited a cost of $70 million to bring its Blue Island refinery up to standards as a reason for shutting down. It also estimated it will need to spend $70 million on its Port Arthur, Tex., plant.

Our internal estimates for several refineries with which we are familiar indicate an investment range of $50 to $90 million, depending upon the existing hardware and feedstocks.

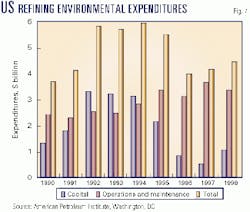

As shown in Fig. 7, environmental expenditures on refining have averaged $5-6 billion/ year. The National Petrochemical and Refiners Association (NPRA) estimates the industry will need to spend $8 billion to comply with gasoline desulfurization alone.

Gasoline-sulfur reduction

Final EPA rules published in February 2000 mandate that average sulfur levels in gasoline be reduced to 30 ppm by Jan. 1, 2005, from a current national average of 300 ppm.

The options available to most refiners to meet the gasoline sulfur specifications include:

- Fluid catalytic cracking (FCC) feed hydro- treating.

- Extractive mercaptan removal from the light FCC naphtha.

- Selective hydrotreating of FCC naphtha.

- Conventional hydrotreating of mid-cut FCC naphtha followed by catalytic reforming.

- Conventional hydrotreating of heavy FCC naphtha, light straight-run naphtha, and coker naphtha.

- Reducing the endpoint of FCC naphtha.

The correct combinations of these options will be unique to each refinery based on its feedstock slate, availability and capability of existing equipment, and refinery-specific economics.

Most refineries will need to employ some type of naphtha hydrotreating process, including those facilities with existing FCC feed hydrotreaters, to obtain a gasoline pool with an average sulfur content of 30 ppm or less.

Diesel-sulfur reduction

An EPA ruling in December 2000 called for on-highway diesel fuel sulfur levels to be reduced to 15 ppm from a current average of 350 ppm. NPRA has challenged that ruling and suggested a 50-ppm standard.

Both options will require new capital investment at the refinery level, but the extent of the hardware investment and the cost of the technology itself will be significantly greater under the 15-ppm standard.

The options available to most refiners to meet the diesel-fuel sulfur specifications include:

- FCC feed hydrotreating.

- Hydrocracking (both gas oil and heavy distillate).

- Severe diesel hydrotreating in a single unit or double hydrotreating.

- Reducing the endpoint of straight-run diesel and FCC light cycle oil.

- Increased production (and possible exports) of off-road diesel and heating oil.

- Increased blending of light cycle oil with fuel oil products.

As with 30-ppm gasoline, combinations of the above processes to produce ultra-low sulfur diesel will be unique to each refiner based on the refinery feedstock slate, the availability and capability of existing equipment, and refinery-specific economics.

Achieving 15 ppm requires the hydro- cracking of certain sulfur-bearing compounds in diesel to allow complete desulfurization to take place. Whether this occurs in a bonafide hydrocracking unit or as one of many reactions that occur in a severe diesel hydrotreating unit, the hydrocracking of these particular compounds, which are primarily found in light cycle oil and the heaviest portion of straight run distillate, will be required to achieve 15 ppm.

The 50-ppm standard proposed by the NPRA will require less capital by virtue of requiring less hydrocracking, which is the most expensive of the options mentioned above. Refiners that already hydrocrack a significant portion of their distillate streams will have an advantage over those that only employ moderate pressure distillate hydrotreating units.

Most of these process options involve a small reduction in distillate-product volume, primarily as a result of the hydro-cracking reactions. This loss, when coupled with potential endpoint reductions and increased production of off-road diesel and heating oil, is likely to reduce the industry's ability to produce on-road diesel by as much as 10%.

Some refiners with limited capital funds and good access to major heating-oil markets may not produce ultra-low sulfur diesel, further reducing the on-road diesel supply.

RFG oxygen content

The possible phase out of methyl tertiary butyl ether (MTBE) and the effects of the RFG-patent infringement court decision are question marks in the future of RFG production.

The Clean Air Act calls for gasoline to contain 2.0 wt % oxygen in those parts of the country failing to meet certain air quality standards. The oxygenate of choice for most areas is MTBE.

In October 1999, a panel appointed by the EPA recommended substantially reducing the use of MTBE due to concerns about groundwater contamination. Still unresolved on a national level is the fate of oxygenates in gasoline in general and MTBE in particular.

California is in the process of phasing out MTBE with a ban effective at the end of 2002. The Oxygenated Fuels Association filed a lawsuit in January to block California's ban on MTBE, and the results will be of wide-ranging significance.

New York state is on track to have an MTBE ban in effect at the end of 2003, and MTBE was recently banned in Chicago. Several other cities and states as well as certain members of Congress are also considering an MTBE ban or phase-out.

In addition, both BP and Tosco (prior to its acquisition by Phillips) have gone on record as supporting a ban.

Although President Bush has not addressed the issue of MTBE, he spoke in favor of increased ethanol use during his election campaign in 2000.

If there is a ban, merchant MTBE producers will likely convert to the production of iso-octane, as there are several competing technologies to do so. Although iso-octane is an attractive gasoline blendstock, it will not deliver the same magnitude of octane improvement provided by MTBE.

Thus, it is unlikely iso-octane production will provide these merchant facilities with the same gross profit margin they enjoyed by producing MTBE.

An alternative to MTBE as an oxygenate is ethanol. Both have similar octane ratings, but ethanol has almost twice as much oxygen content.

Thus, it takes about half the volume of ethanol to be added to a given quantity of gasoline to meet the 2.0 wt % oxygen requirement.

On the other hand, that given quantity of gasoline will get approximately half the octane boost. Thus, the original gasoline will need to be of slightly higher octane if ethanol is used. Refiners can deal with the octane loss due to MTBE displacement by:

- Increased alkylation.

- Purchase of merchant iso-octane from former MTBE producers.

- Increased reformer severity.

- Increased light naphtha isomerization.

- Reduced production of premium gasoline.

- Lowering the road octane of premium gasoline from it current level of 93 to 92 or 91.

RFG patent infringement

An additional uncertainty for gasoline production is the resolution of the Unocal Corp. patent on RFG blending formulas, known as the "393 patent," issued in February 1994.

Five major oil refiners challenged the validity of the patent, claiming it was anticipated by prior art (that is, by prior methods or prior technologies) used in the industry.

The courts ruled in favor of Unocal, and upheld its right to collect 5.75 ¢/gal in back royalty payments.

The five plaintiffs have petitioned the Supreme Court to reverse that ruling, but the Solicitor General's office, on the last day of the Clinton administration's tenure, filed a brief for the US as "amicus curiae," recommending that the suit does not warrant review.

The issue of concern to the industry is that the Unocal recipe is so broad in its scope that refiners and gasoline blenders may find it difficult to develop gasoline recipes different enough from those of Unocal to avoid patent infringement claims. This has prompted refiners to more closely control how they blend RFG.

Most refiners in California have avoided infringement by more carefully blending their various grades of gasoline to stay above a T50 point of 210° F. This procedure has reduced the effective application of "393" to gasoline with an octane rating of 92 or more and an RVP of 7.5 or less.

Thus, the nationwide impact appears limited at this time. However, fear of infringing the patent has been claimed as a contributing factor in the past year's Midwest gasoline shortage, and it will probably continue to be a regional supply-suppressing factor in isolated instances.

Of additional concern are the subsequent patents granted to Unocal that essentially broaden the scope of "393." The upshot of this for the immediate future is that there may be fewer opportunities to produce RFG that avoids infringement purely through careful blending.

Price volatility

Tighter inventories, speculative trading, and variable operating costs are contributors to present and future fuel-price volatility.

Tighter inventories

A pervasive trend throughout the world has been the paring down of inventory levels in line with the "just in time" concept of inventory management. This concept has become an integral part of the refining industry on both feedstock supply and refined-product storage.

The paring down of inventory in terms of "days of supply" has been dramatic in the past few years, but it is a trend that cannot continue much longer.

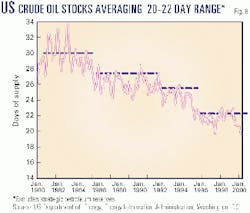

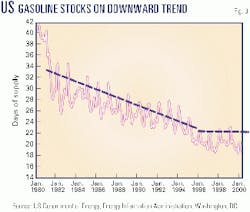

Crude-oil stocks, which averaged 28-30 days of forward supply in the early 1980s, are now averaging 20-22-days (Fig. 8). Gasoline stocks have been on a similar downward trend (Fig. 9).

Because of these lean inventories, relatively minor interruptions of supply have a disproportionate impact on market prices and refinery margins. This volatility will not only continue into the future but will heighten as cleaner fuels are phased in.

Speculative trading

Speculative trading in the paper-barrel market has a huge effect on day-to-day price swings despite relatively little change in supply and demand fundamentals.

The year 1983 marked an important point in the evolution of crude-oil pricing. In March of that year the New York Mercantile Exchange (NYMEX) began trading the light sweet crude-oil contract, and in July, Platts began publishing daily spot crude-oil prices.

Before then, almost all information on crude prices was derived from the price bulletins issued by the major refiners. These "posted prices" generally remained the same for weeks or months at a time. As an example, Exxon's posted price for non-controlled WTI only changed once from January 1977 to December 1978.

Since the mid-1980s, the wet-barrel market has dominated the spot market, which in turn has become dominated by the NYMEX and London's International Petroleum Exchange (IPE) paper markets. On average, the volume of crude oil traded on the NYMEX is ten times the volume of crude actually used in US refineries.

Gasoline and heating oil also trade on the NYMEX allowing traders to speculate on the size of the crack spread as well as the level of prices.

Speculators are relatively indifferent to the absolute level of crude oil and refined products prices or the size of the crack spread. They care about the direction of movement, whether the crack goes up or down. They can make money if they are on the right side of the transaction.

While refiners are also somewhat indifferent to the absolute level of crude oil and refined products prices, they critically depend on the size of the crack spread. To a great degree, the crack spread has become randomized by the dominant market participants who have more interest in the crack's direction than its size.

Thus, refiners have moved from their historical position of controlling gross margins through the posting process to having little or no influence on this key component of profitability. Refiners instead concentrate on feedstock selection and capturing wider margins from heavy sour crudes.

Variable operating costs

Variable costs of operation have been under closer scrutiny for years. This scrutiny will intensify as energy costs to refiners increase.

Until a few months ago, natural gas and electricity prices, although important, were taken for granted. Suddenly, at the end of 2000 and the beginning of 2001, these operating costs are in the forefront of the planning and operations control.

Although we are not particularly confident in forecasting the future of natural gas and electricity prices, we are certain these prices will be a driving force in future operating decisions as the btu value vs. sales value of almost every refining stream becomes more closely monitored.

Product demand/supply balance

Petroleum demand reached an estimated record level of 19.6 million b/d in 2000. Refineries ran at high rates of utilization, and refinery crude-oil input also reached record levels.

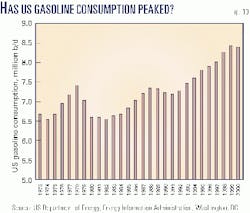

Interestingly, gasoline consumption fell slightly in 2000, the first decline since 1991 (Fig. 10). As these data are preliminary, it would not be surprising to see them revised upward.

The statistic does question whether or not gasoline demand is reaching a peak in the US. The current high demand for sport-utility vehicles (SUVs) and light trucks tends to lower the average fuel economy of the fleet.

This, combined with the economic growth of 2000, would make one suspect that consumption is on the rise. Gasoline prices may be now high enough, however, to have a noticeable effect on driving patterns.

Gasoline and other refined product demand are likely to remain high. There may be less growth if a recession occurs, however. Although slower economic growth may slacken product demand this year, refiners will have a difficult time meeting domestic demand over the next 5 years as the economy recovers.

The Annual Energy Review 2001 published by the US Energy Information Administration (EIA) has a base-case projection of refined products demand increasing by 1.7 million b/d from 1999 to 2005. This is accommodated by a slight increase in imports and a 1.2 million-b/d increase in refining-distillation capacity.

This 1.2 million-b/d of capacity creep will be very difficult to accomplish, however. During the next 5 years, refiners will focus their investment activities on clean-fuels projects, investments that add nothing to overall refining capacity.

Moreover, it is reasonable to assume that a great deal of the more easily accomplished capacity enhancements to existing units has already been done. Further, it is quite likely that several refineries will shut their doors because they cannot make Tier II gasoline.

As well as a reduction in gasoline make, there is a possible contraction of refineries' on-road diesel product yield caused by the severity of the new specifications.

Traditional exporters of refined products to the US, such as Canada, Venezuela, Saudi Arabia, and Europe, will encounter increased difficulty making US specification products. Maintaining their previous levels of exports may be challenging enough, let alone increasing them.

While these imports do not form a foundation for US product supply, they are vitally important during periods of peak demand.

Fuel efficiency has recently been revived as a major theme of automobile manufacturers, especially in regard to SUVs. More fuel-efficient vehicles will hit the street in a few years, but it will take several more years for newer models of cars and trucks to penetrate the market enough to counteract the natural expansion in the number of drivers and miles driven.

Until then, there will be a tightness in the transportation fuels market accompanied by occasional price spikes. This environment should result in stronger gross margins for refiners.

The authors

Joseph Loftus is senior economist of Turner, Mason & Co. He is responsible for crude oil and refined product market analysis. He has more than 30 years' experience in both consulting and in industry, including positions with Air Products and Chemicals and Mobil Oil. Loftus holds a BA in economics from the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and an MA in economics from Temple University, Philadelphia.

James Jones is a vice president and principal of Turner, Mason & Co. He is responsible for technical and economic studies of refineries and refining companies. Previously, he was with LaGloria Oil and Gas Co. where he served as operations manager of its Tyler, Tex., refinery. Jones holds a BS in chemical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin and an MBA from the University of Texas at Tyler.

John W. Huggins is a senior consulting engineer and principal of Turner, Mason & Company. He has more than 30 years' experience in the refining industry, including management positions with Conoco, Mapco Petroleum, and Frontier Refining. Huggins has both BS and MS degrees in chemical engineering from Oklahoma State University, Stillwater.